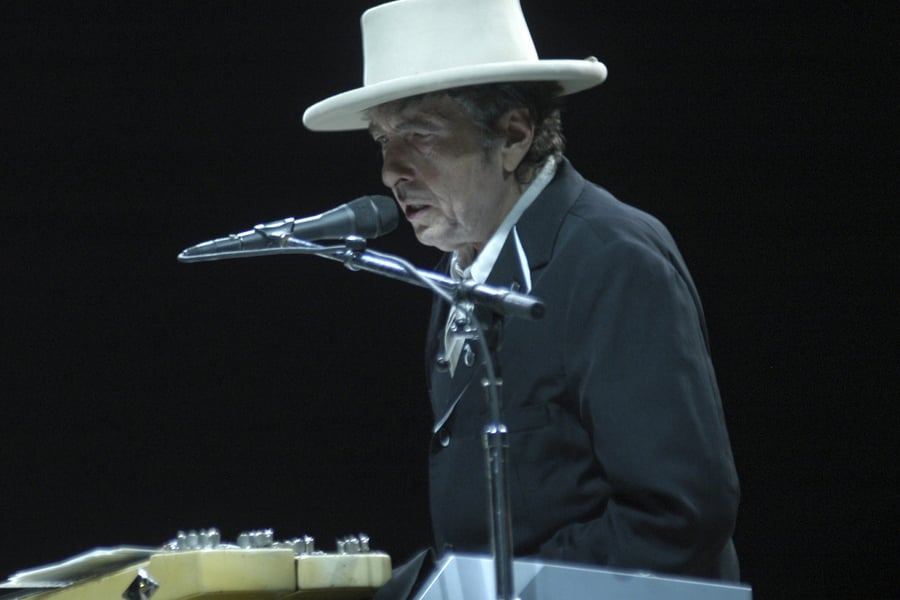

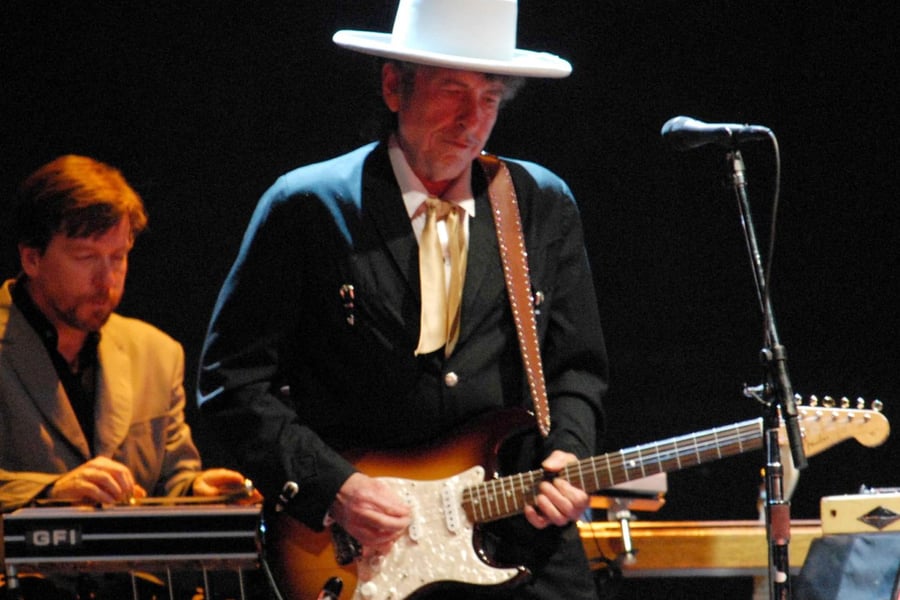

The 25 Best Bob Dylan Songs of the 21st Century

In the years since 2000, Dylan has renewed his creative energy and produced a catalog of songs that stand alongside any past era of his career

Kevin Winter/Getty Images

“Things should start to get interesting right about now,” Bob Dylan sang in “Mississippi,” and he wasn’t kidding. At the end of the 20th century, he was 58 years old, one of the most worshipped, most mythologized, most misunderstood artists alive, and far from finished. Over the next two decades, he’d change the very structure of his music, using more sophisticated chords than he’d ever attempted before, turning to jazz and the pre-rock standards he’d helped overthrow for inspiration, while finally finding peace with the recording process, which had vexed him for decades. He pushed the limits of his magpie ways, borrowing riffs and phrases both verbal and musical from every conceivable source, while (almost) always alchemizing them into something new. He could be vicious (“Pay in Blood”) or strikingly playful (“I Contain Multitudes”), revisiting the absurdist wit of his Basement Tapes-era writing, or digging into the blues with a mastery that shames even his Sixties high points in that vein. He’s 79 now, and his fantastic new album, Rough and Rowdy Ways, is his latest definitive proof that youth and inexperience are thoroughly overrated.