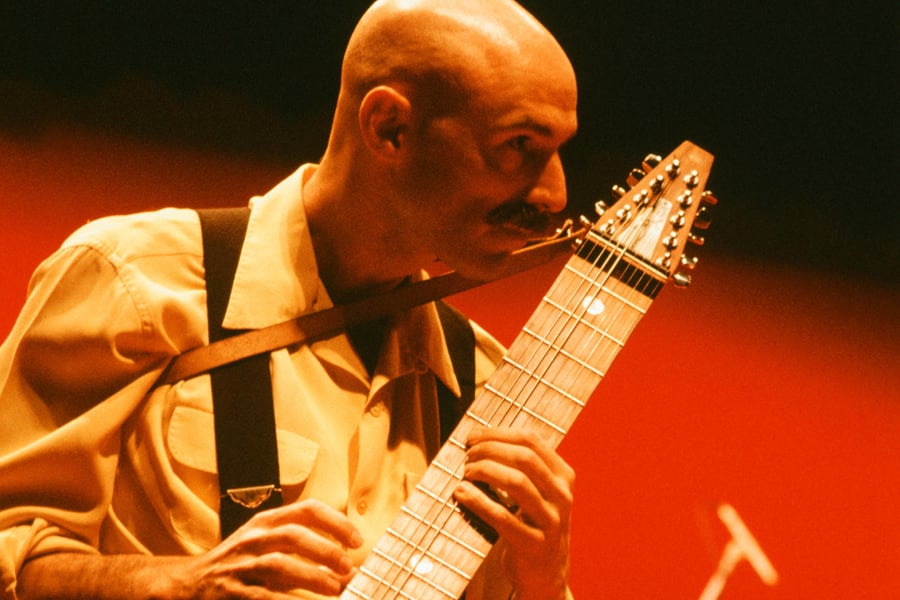

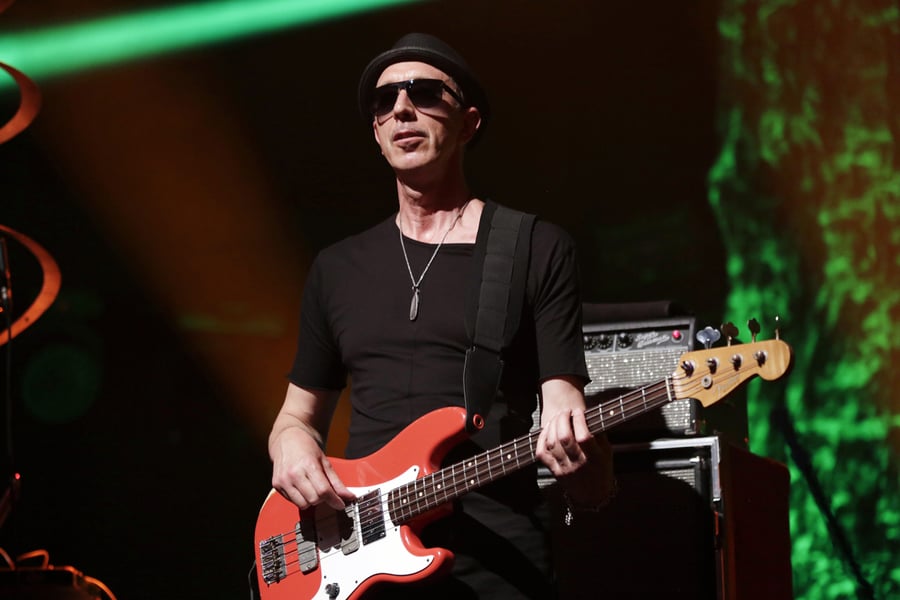

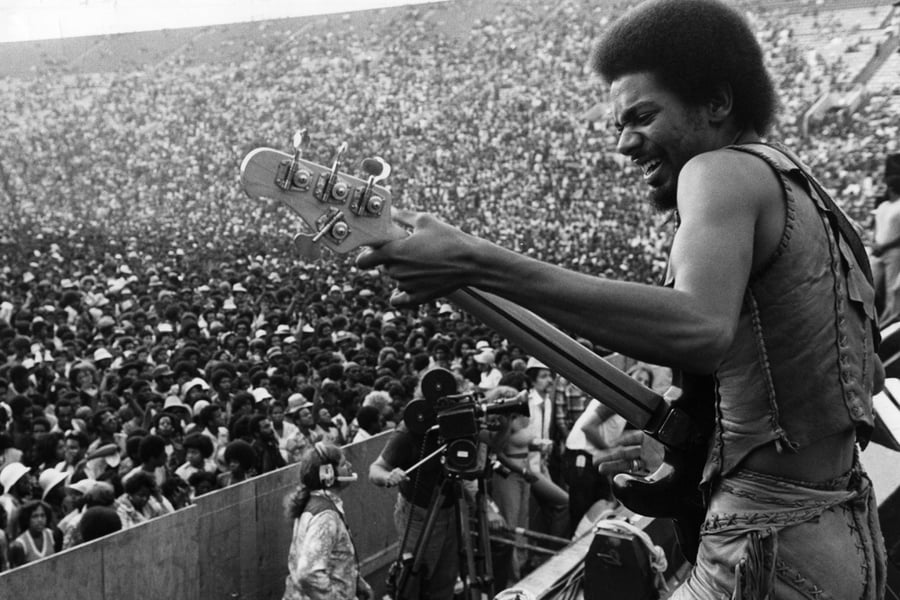

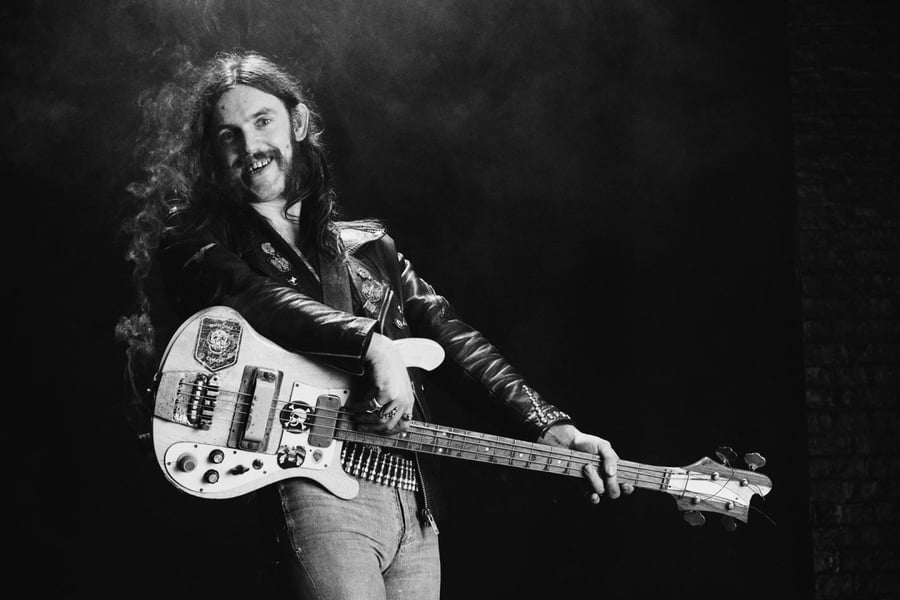

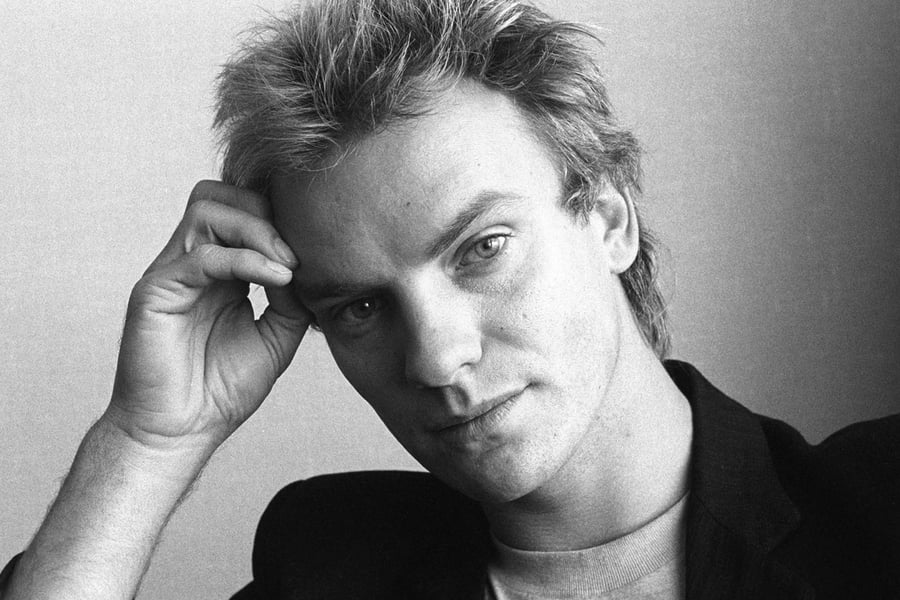

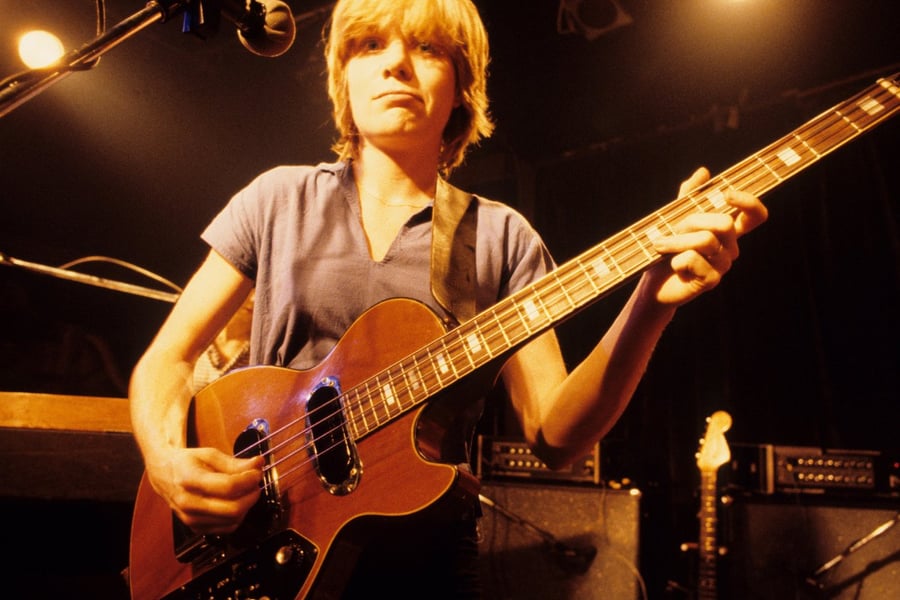

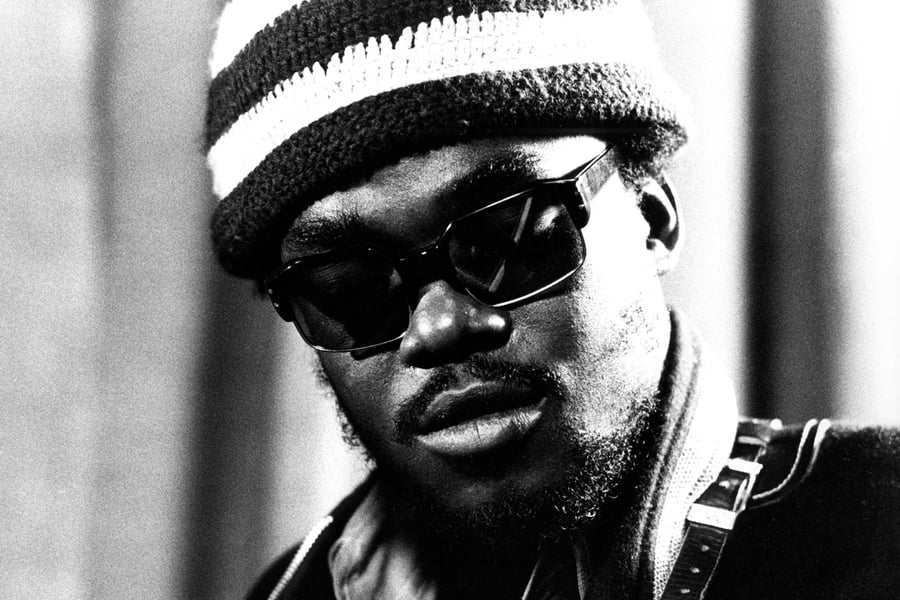

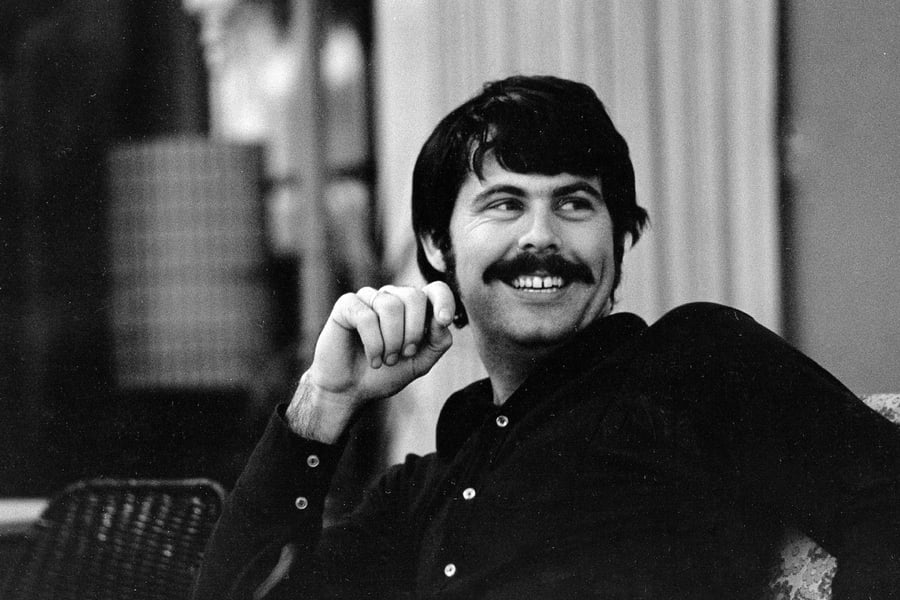

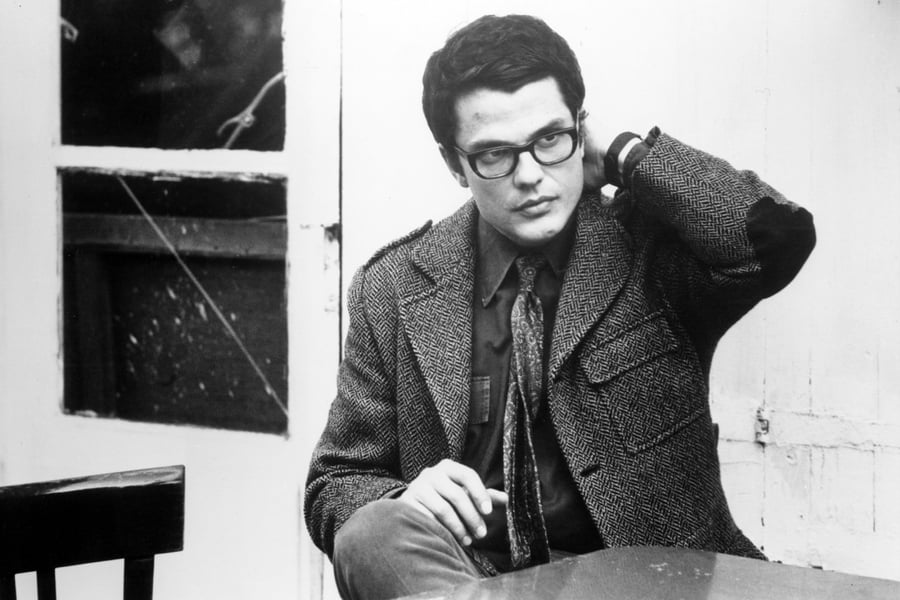

The 50 Greatest Bassists of All Time

From funk masters to prog prodigies and beyond, we count down the players who have shaped our idea of the low-end theory

We count down the 50 greatest bassists of all time, from string-popping virtuosos to steady session heroes.

Photographs used in illustration by AP/Shutterstock; Joseph Okpako/WireImage; Elaine Thompson/AP/Shutterstock

“The bass is the foundation,” session legend Carol Kaye once said, “and with the drummer you create the beat. Whatever you play puts a framework around the rest of the music.”

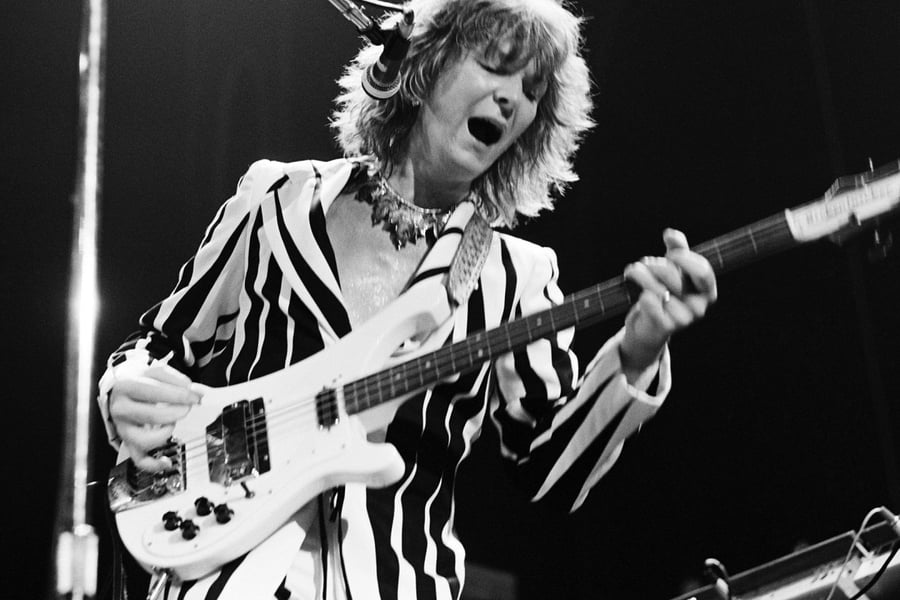

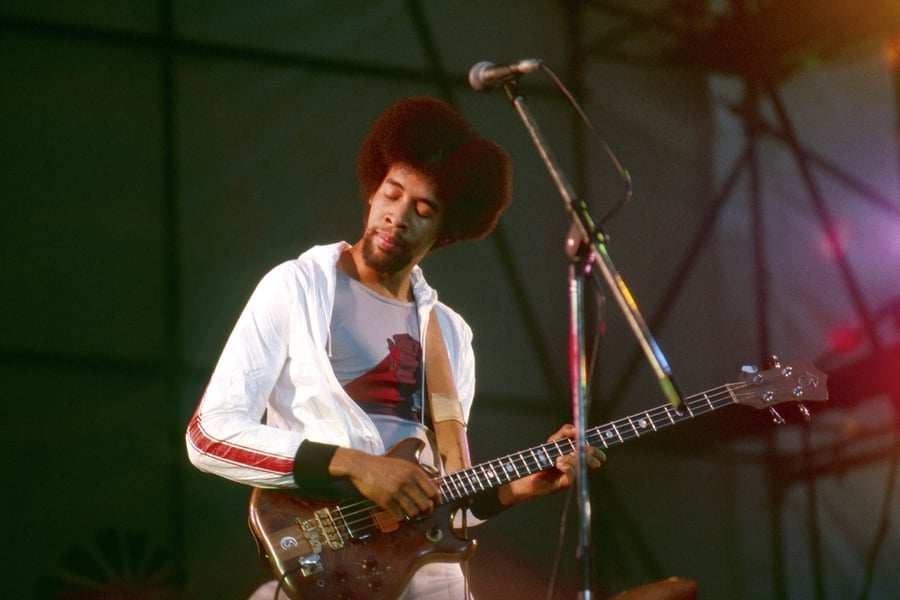

A great bass line, whether it’s Paul McCartney’s hypnotic “Come Together” riff, Bootsy Collins’ sly vamp from James Brown’s “Sex Machine,” or Tina Weymouth’s minimal throb on Talking Heads’ “Psycho Killer,” is like a mantra: It sounds like it could go on forever, and it only feels more profound the more you hear it. Guitarists, singers, and horn players tend to claim the flashiest moments in any given song, while drummers channel most of the kinetic energy, but what the bassist brings is something elemental — the part that loops endlessly in your head long after the music ends.

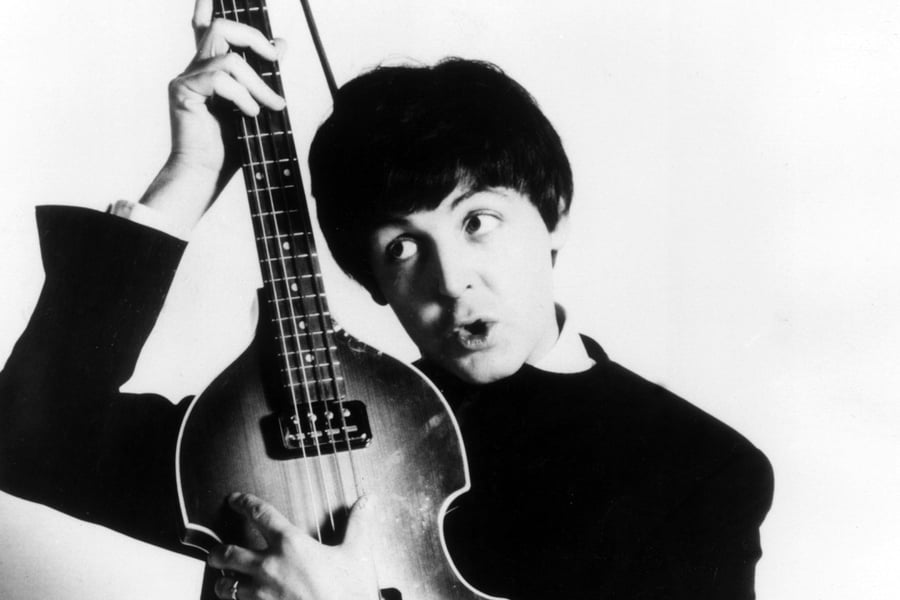

Bassists are often overlooked and undervalued, even within their own bands. “It wasn’t the number-one job,” McCartney once said, reflecting on the fateful moment when he took over the four-string after Stu Sutcliffe exited the Beatles. “Nobody wanted to play bass, they wanted to be up front.”

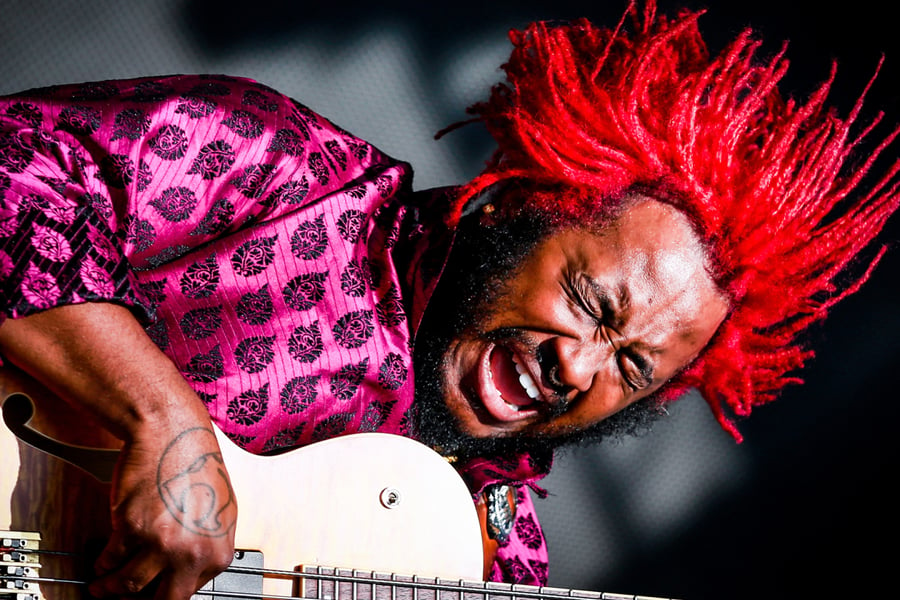

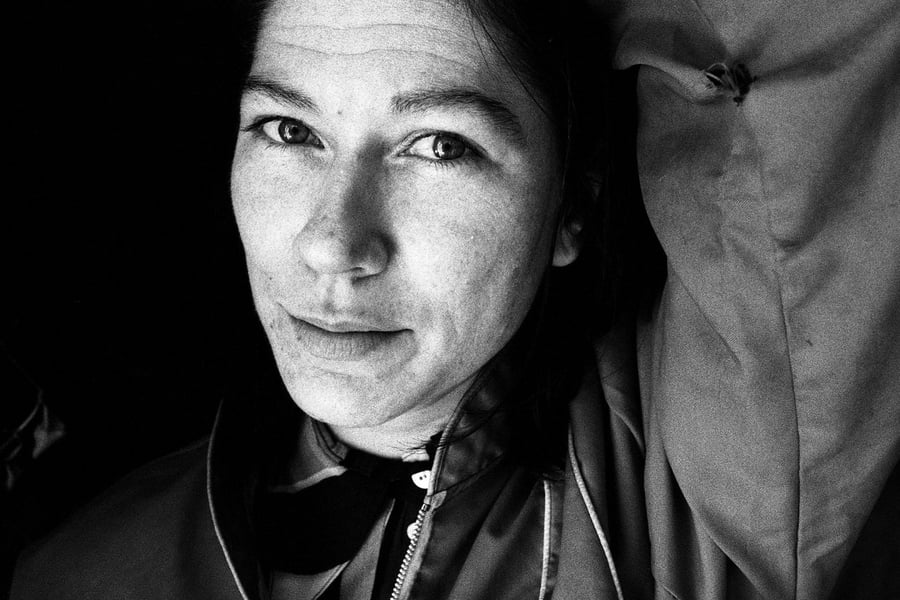

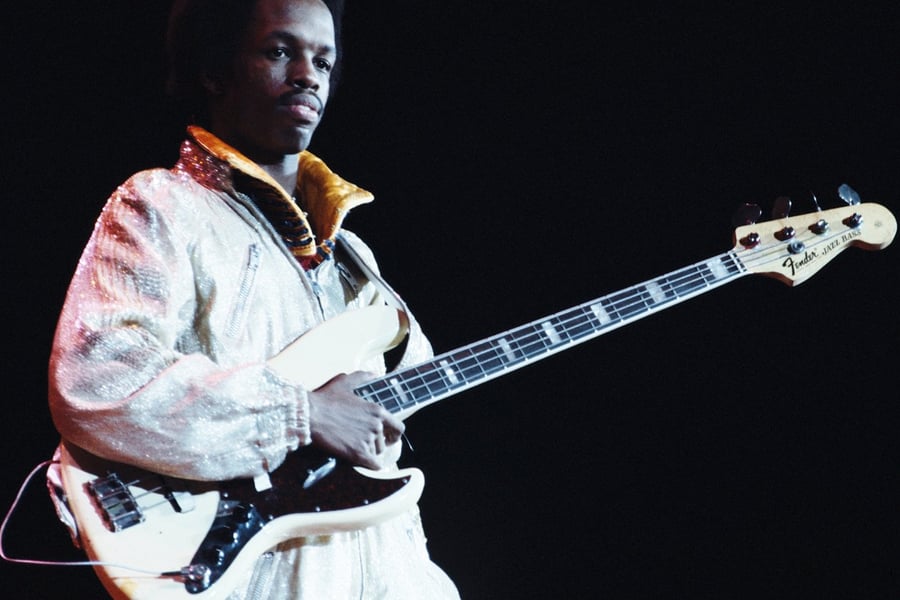

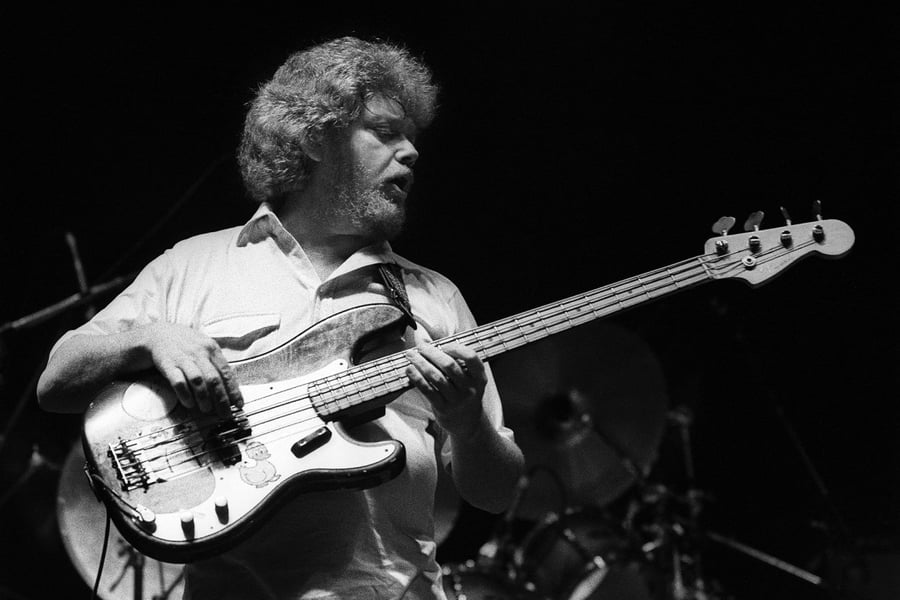

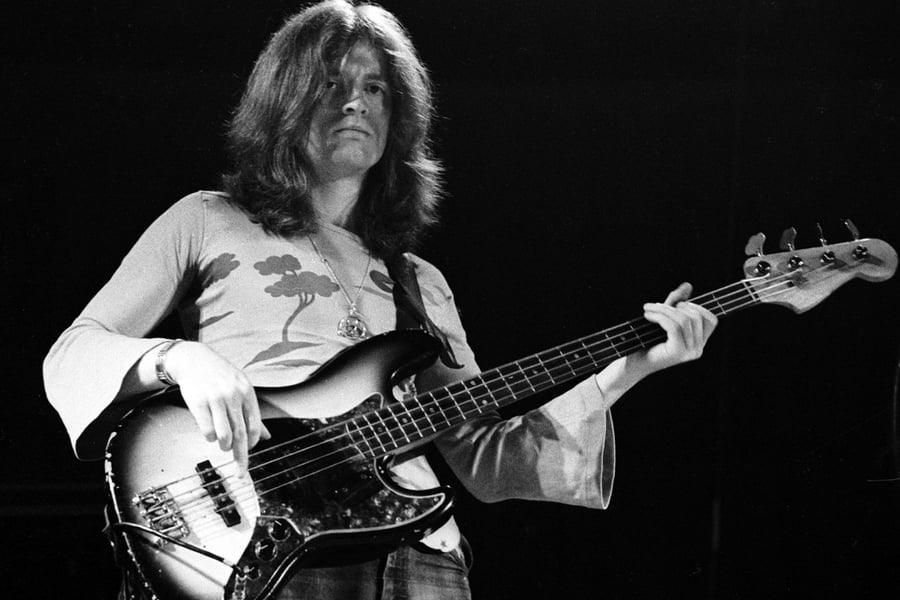

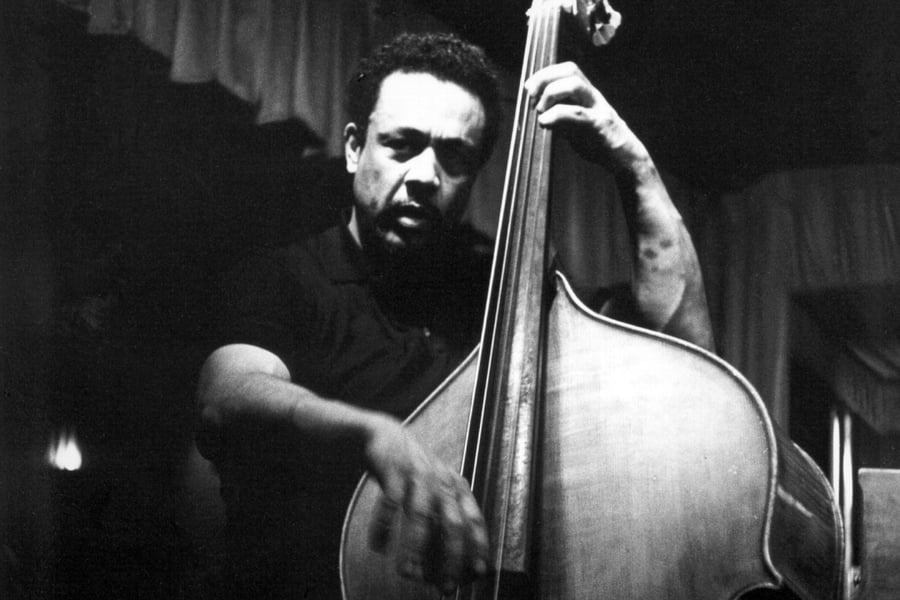

And yet the instrument has its own proud tradition in popular music, stretching from the mighty upright work of Jimmy Blanton in Duke Ellington’s orchestra and bebop pioneers like Oscar Pettiford to fellow jazz geniuses like Charles Mingus and Ron Carter; studio champs like Kaye and James Jamerson; rock warriors like Cream’s Jack Bruce and the Who’s John Entwistle; funk masters like Bootsy and Sly and the Family Stone’s Larry Graham; prog prodigies like Yes’ Chris Squire and Rush’s Geddy Lee; fusion gods like Stanley Clarke and Jaco Pastorius; and punk and postpunk masters like Weymouth and the Minutemen’s Mike Watt. The alternative era brought new heroes on the instrument, from Sonic Youth’s intuitive Kim Gordon to Primus’ outlandish Les Claypool, and more recently, a fresh crop of bass icons — including Esperanza Spalding and the ubiquitous Thundercat — have placed the low end at the center of their musical universes.

As with our 100 Greatest Drummers list, this rundown of the 50 greatest bassists of all time celebrates that entire spectrum. It’s emphatically not intended as a ranking of objective skill; nor does it assign any one set of criteria as a measure of greatness. Instead it’s an inventory of the bassists who have had the most direct and visible impact on creating, to borrow Kaye’s term, the very foundation of popular music — from rock to funk to country to R&B to disco to hip-hop, and beyond — during the past half-century or so. You’ll find obvious virtuosos here, but also musicians whose more minimal concept of their instrument’s role elevated everything that was going on around them.

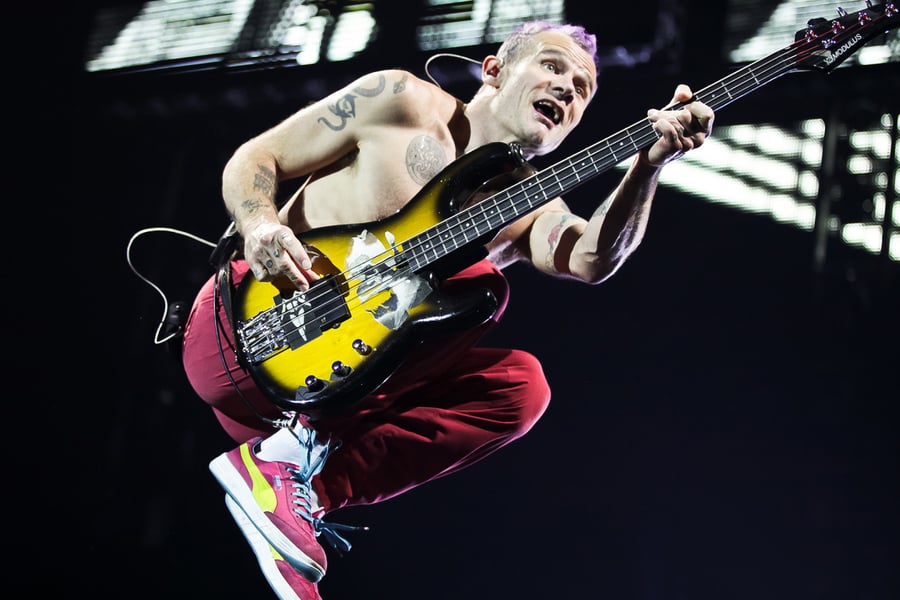

“You grab it, slide around on it, and feel it with your hands,” Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea once said of his signature instrument. “You slap, pull, thump, pluck, and pop, and you get yourself into this hypnotic state, if you’re lucky, beyond thought, where you’re not thinking because you’re just a conduit for this rhythm, from wherever it comes from, from God to you and this instrument, through a cord and a speaker.”

Here we pay tribute to 50 musicians who have found that same exalted state via the bass, and changed the world in the process.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.