100 Greatest Bob Dylan Songs

From “Just Like a Woman” to “John Wesley Harding,” we count down the American icon’s key masterpieces

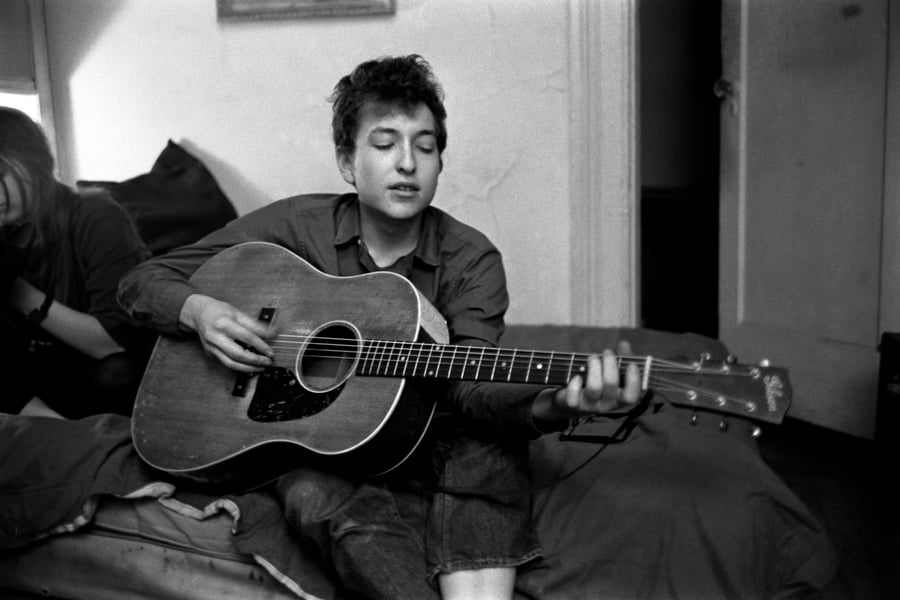

Ted Russell/Polaris

For generations to come, other artists will be turning to Bob Dylan’s catalog for inspiration. From the Sixties protest anthems that made him a star through to his noirish Nineties masterpieces and beyond, no other contemporary songwriter has produced such a vast and profound body of work: songs that feel at once awesomely ancient and fiercely modern. Here, with commentary from Bono, Mick Jagger, Lenny Kravitz, Lucinda Williams, Sheryl Crow and other famous fans, are Dylan’s 100 greatest songs – just the tip of the iceberg for an artist of his stature.

[This list originally appeared in a 2015 Special Edition]