Bono: That sneer – it’s something to behold. Elvis had a sneer, of course. And the Rolling Stones had a sneer that, if you note the title of the song, Bob wasn’t unaware of. But Bob Dylan’s sneer on “Like a Rolling Stone” turns the wine to vinegar.

It’s a black eye of a pop song. The verbal pugilism cracks open songwriting for a generation and leaves the listener on the canvas. “Rolling Stone” is the birth of an iconoclast that will give the rock era its greatest voice and vandal. This is Dylan as the Jeremiah of the heart. Having railed against the hypocrisies of the body politic, he starts to pick on enemies that are a little more familiar: the scene, high society, “pretty people” who think they’ve “got it made.” He hasn’t made it to his own hypocrisies – that would come later. But the “us” and “them” are not so clearly defined as earlier albums. Here he bares his teeth at the hipsters, the idea that you had a better value system if you were wearing the right pair of boots.

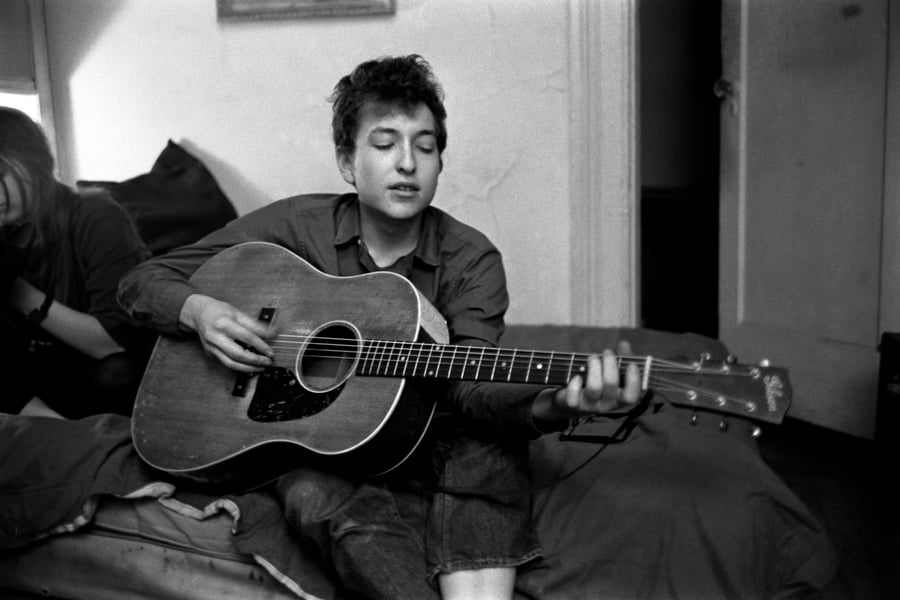

For some, the Sixties was a revolution. But there were others who were erecting a guillotine in Greenwich Village not for their political enemies, but rather for the squares. Bob was already turning on that idea, even as he best embodied it, with the corkscrew hair Jimi Hendrix imitated. The tumble of words, images, ire and spleen on “Rolling Stone” shape-shifts easily into music forms 10 or 20 years away, like punk, grunge or hip-hop. Looking at the character in the lyric, you ask, “How quickly could she have plunged from high society to ‘scrounging’ for her ‘next meal’?” Perhaps it is a glance into the future; perhaps it’s fiction, a screenplay distilled into one song.

It must have been hard to be or be around Dylan then; that unblinking eye was turning on everybody and everything. But the real mischief is in its ear-biting humor. “If you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose” is the T-shirt. But the line that I like the best is “You never turned around to see the frowns on the jugglers and the clowns/When they all did tricks for you/You never understood that it ain’t no good/You shouldn’t let other people get your kicks for you.”

The playing on this track – by the likes of guitarist Mike Bloomfield and keyboardist Al Kooper – is so alive that it’s like you’re getting to see the paint splash the canvas. As is often the case with Bob in the studio, the musicians don’t fully know the song. It’s like the first touch. They’re getting to know it, and you can feel their joy of discovery as they’re experiencing it.

When the desire to communicate is met with an equal and opposite urge not to compromise in order to communicate is when everything happens with rock & roll. And that’s what Dylan achieved in “Rolling Stone.” I don’t particularly care who this song is about – though I’ve met a few people who have claimed it was about them (some who weren’t even born in 1965). The thrill for me was that “once upon a time,” a song this radical was a hit on the radio. The world was changed by somebody who cared enough about an unrequited love to write such a devastating put-down.

I love to hear a song that changes everything. That’s the reason I’m in a band: David Bowie’s “Heroes,” Arcade Fire’s “Rebellion (Lies),” Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart,” Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing,” Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.” But at the top of this dysfunctional family tree sits the king of spitting fire himself, the juggler of beauty and truth, our own Willy Shakespeare in a polka-dot shirt. It’s why every songwriter after him carries his baggage and why this lowly Irish bard would proudly carry his luggage. Any day.