It’s time to make “Y.M.C.A.” great again. People in the streets of Philadelphia are dancing to “Y.M.C.A.” in celebration of the news that Joe Biden has taken the lead in Pennsylvania. That means he’s nearly clinched the presidential race — hopefully to be called tonight. The Village People’s Seventies disco classic is extra spicy because Donald Trump spent the year using “Y.M.C.A.” at his campaign rallies as his theme song, along with another Village People classic, “Macho Man.” For any disco fan, it’s appalling to see this fascist-phobe clown in his red MAGA cap doing the Y.M.C.A. dance.

So “Y.M.C.A.” is more than a song. It’s a battle for the soul of America. What does it mean that the most politically divisive song of 2020 is a 1978 disco anthem about cruising for sex at your local gym?

It’s just part of the long strange story of “Y.M.C.A.” and its 42-year journey through the heart of American culture. Why exactly did this President, a blatant white supremacist who’s spent the past four years sucking up to actual Nazis — “very fine people,” in his words — choose this disco hit as his personal “Tomorrow Belongs to Me”? Why are Republicans out to claim this song? And why is it so cathartic to steal it back?

The Village People laughed at the idea of making political statements back in the day. As David Hodo, the Construction Worker, told Rolling Stone in 1979, “We as a group don’t like labels, don’t like black-white, straight-gay, disco-rock & roll. Whatever. We’re not Joan Baez.” But there’s just something about this song — every corner of American culture wants a piece of it. As everybody’s favorite Village Peep, the late great Glenn Hughes, the Leather Man, told RS in 1978, “It’s real, it’s basic, it’s clean-cut, it’s American.”

Yet another irony: It’s tougher than ever to stay at the Y.M.C.A. because of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Trump administration’s criminal negligence. The Y.M.C.A. in my neighborhood has been locked up for the past eight months — it’s no longer a place where you can get yourself clean, have a good meal, or do whatever you feel. You couldn’t get through the door to do a push-up, much less blow a construction worker.

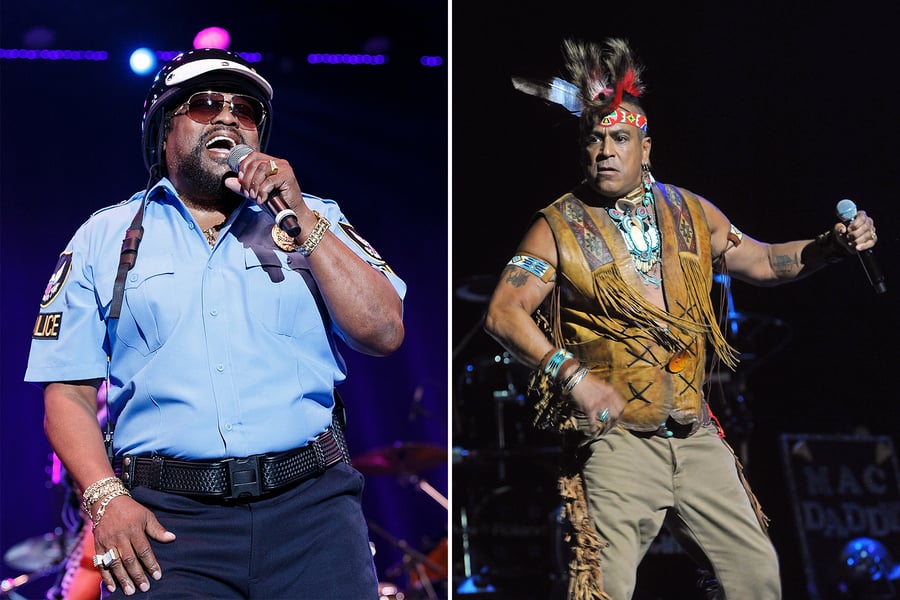

Even the Village People have been bitterly divided about Trump and “Y.M.C.A.” It’s a complicated story because of the long-running legal battle over the trademark, but in 2017, long-gone singer Victor Willis (the Cop) won the rights to the name. His social media posts have suggested approval of Trump using the song. On November 3rd, Election Day, he posted, “Y.M.C.A. has broken into iTunes top 20, thanks to @realDonaldTrump.” He also posted, “Sorry haters, but thanks to @realDonaldTrump Y.M.C.A. by @WeVillagePeople is #11 on @billboard Digital Sales Chart this week, and rapidly climbing. Will break into the top 10 any day now! Thank you @realDonaldTrump.”

Through his publicist, Willis tells Rolling Stone: “I’ve consistently stated that neither me, nor Village People, endorsed his use of our music and we did demand he cease and desist back in June. However, copyright law made it possible for him to ignore us. As a result, we were never in a position to bring a viable suit in an attempt to stop his use. That is why I’m asking artists and copyright owners to join me in an effort to lobby changes to blanket licensing. Admittedly though, his use resulted in Y.M.C.A returning to the charts after over 40 years. So, I have to at least credit his campaign for this resurgence.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Felipe Rose, the Indian Chief back in the day, is not having it. (And yes, he’s Native American — Lakota on his father’s side. His solo single, a cover of Lamont Dozier’s “Going Back to My Roots,” won Best Dance Single at the 2018 Native American Music Awards.) On Twitter, he posted a video where he sees Trump on TV, gives a battle cry, and beats the president to the ground. What could be more 2020 than the fact that you have to choose between the Cop and the Indian?

This summer, Willis complained about Trump using the song, especially during the Black Lives Matter protests. “If Trump orders the U.S. military to fire on his own citizens (on U.S. soil), Americans will rise up in such numbers outside of the White House that he might be forced out of office prior to the election. Don’t do it Mr. President! And I ask that you no longer use any of my music at your rallies especially “‘Y.M.C.A.’ and ‘Macho Man.’ Sorry, but I can no longer look the other way.”

Willis has also been complaining on social media about the fact that people associate this song with 1970s gay culture. (Talk about a lost cause.) He recently threatened: “I will sue the next media organization, or anyone else, that falsely suggests ‘Y.M.C.A.’ is somehow about illicit gay sex. Get your minds out of the gutter please! It is not about that!”

It’s part of the long strange story of “Y.M.C.A.,” a song that sums up so much of America in four minutes, linking the amyl sweat of Studio 54 with the locker rooms of the Young Men’s Christian Association. If you were a little kid in the Seventies, the Village People were your first encounter with proudly uncloseted gay culture. I was just a child when “Y.M.C.A.” was a hit, but even I could hear that something was going on here. The Village People got even more brazen in the follow-up, “In the Navy.” (“Come protect the motherland! Come on and join your fellow man!”) They also did “Go West,” “Hot Cop,” and my personal favorite, “My Roommate.” But it was over way too soon, with their swan songs “Sex on the Phone” and “Ready for the 80s.”

Producer Jacques Morali, who formed the group, based it on his European outsider’s fantasy of American culture. He was inspired by visiting NYC’s gay discos and seeing dancers from all different races and cultures getting down. As Morali told Rolling Stone, “I am gay, you know, myself, so I am not the kind of person to joke about the statement. Because it’s my statement, you know? Knowing that the group is gay, that I’m really believing and trusting what I’m doing, it’s not a parody at all.” For him, there was something utopian about it. “I don’t think that straight audiences know that they are a gay group. Victor Willis is not gay but all of them can work together, which is what America is trying to do.”

The Village People were largely seen as a lovable cartoon, but that allowed them to get away with flaunting gay codes in their music that other artists might have found too risky. As Glenn Hughes said: “A foreigner comes to Greenwich Village, what he sees is very strong, positive male American stereotypes. From a foreign frame of mind, there’s a whole mysticism attached to an ‘American,’ and here he’s seeing it in bigger-than-life stereotypes.”

Strange as it might seem now, “Y.M.C.A.” was a totally forgotten song for many years. It ruled the radio for a couple of months in 1978, but then it vanished for the next decade. There is zero chance you heard it anywhere in the wild for most of the Eighties. In 1988, Rhino Records dropped a Village People Greatest Hits compilation, the first time in years the songs were commercially available. I bought the tape on my lunch hour (eight bucks) and spent the afternoon at work pumping it on my Walkman. I remember the full-body pheromone rush of hearing “Y.M.C.A.” for the first time in years: That bass! Those horns! Those deeper-than-deep macho choir chants! This song was even better (and funnier) than any of us remembered.

But when this song came back, it came back all the way. By the early Nineties, it was everywhere: It no longer seemed weird to see my mom on the dance floor at a Catholic wedding busting out her “Y.M.C.A.” moves. The song was suddenly everywhere. There is no public event in American life where it sounds out of place. You wouldn’t be surprised to hear it at any wedding, sporting event, religious ceremony or cruise ship. It’s become one of our national anthems — yet fans got outraged at the idea of Trump trying to claim this one, which is why it became far more controversial than his other musical picks. Y.M.C.A. yes, MAGA no.Donald Trump had to find out the hard way, but he is not one of the Village People. He is not a strange but beautiful freak artifact of American culture that will be cherished by all corners of the populace for generations to come. He’s not a Cowboy, a Construction Worker, a Chief, a Cop, or God knows, a Leather Man. He is not timeless. He is not beloved. He is not disco. And as of January 21st, he will be no longer welcome in his current residence.

But don’t worry, old man — we hear there’s a place you can go, when you’re short on your dough. When all else fails, it’s fun to stay at the Y.M.C.A.

From Rolling Stone US