Albrecht La'Brooy*

It's one of the most beloved yet misunderstood genres around the world, but how did ambient music find its mainstream following?

If architecture really is “frozen music”, as Goethe said, then airports are the closest thing we have to defrosted architecture. They look the way they sound: sterile, anonymous structures of glass and concrete, the melody of rushing feet and horrible background static, announcements, trolley wheels, frying oil, tax-free cigarettes, and the white noise of thousands of people just waiting, waiting, waiting for deliverance. Airports are like a punch to the eardrum.

Strange then, that an airport spawned an entire genre of music and inspired what might be the most original and unusual album of all time. The story goes like this. Legendary musician and producer Brian Eno was waiting in Cologne airport, Germany, in the Seventies, when he looked around and started listening. “The light was beautiful, everything was beautiful,” Eno said later, “except they were playing awful music. And I thought, there’s something completely wrong that people don’t think about the music that goes into situations like this. They spend hundreds of millions of pounds on the architecture, on everything. Except the music.”

“I thought, there’s something completely wrong that people don’t think about the music that goes into situations like this.”

Eno set to work composing. He imagined an empty airport, late at night, when the bustle of movement has died away, and the world is quiet and soft, and all you can see are “planes taking off through smoked windows”. The project became Music For Airports, the first recognised ‘ambient’ album ever produced. Eno himself coined the term ‘ambient’ to distinguish this new sound from the hellish corporate muzak that gets piped into elevators everywhere. Those tinny earworms that burrow into your ear canal and lay eggs. “I wanted to hear music that had not yet happened,” he said.

That was 42 years ago, but Music For Airports still feels like some strange and beautiful seashell, washed up on an alien shore. It’s the noise of the universe’s waiting room: a dreamy mix of piano, soupy static, android choirs, and pulsing cello that hits your brain like an Ambien. You can only imagine how weird it must have sounded at the time. In 1978, the Billboard charts featured “Stayin’ Alive” by the Bee Gees, “Grease” by Frankie Valli, and “Boogie Oogie Oogie” by Taste of Honey, and here comes Brian Eno with, essentially, 48 minutes of musical mind soup. No beat, no vocals, no traditional melody, nothing you can dance to, no hook or bridge. Just a lasagne of sonic textures. Eno said his mission was to make music that was “as ignorable as it is interesting”, which is still the best definition of ambient going around.

You can find ambient’s musical fingerprints everywhere. The genre includes Erik Satie’s melancholy “Gymnopédies” (which John Cage famously called “furniture music”); Pierre Schaeffer’s experimental, spliced-up tape loops from the Forties; Max Richter’s 2002 classical mind-fuck, Memoryhouse; and even Cage’s famous three-movement 1952 composition, “4’33”, which is literally four minutes and 33 seconds of silence, intended to capture the soundscape of wherever it’s ‘played’ (musicians are instructed to bring their instruments, unpack them, then sit there and do nothing).

“4’33” is maybe the most out there expression of ambient music, but the whole point of the track, maybe the whole point of the genre, is to fudge the line between music and sound. Before composing “4’33”, Cage visited an anechoic chamber—a specially designed room of absolute, noise-absorbing non-sound—and was surprised by what he heard. “I heard two sounds,” he wrote later, “one high and one low. When I described them to the engineer, he informed me that the high one was my nervous systems in operation, the low one my blood in circulation.” Expecting silence, Cage found music. The pulse and melody of his own body.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“A lot of ambient came from musicians and artists who were making techno and house music,” say Sean La’Brooy and Alex Albrecht from Australian ambient label, Analogue Attic. “They started taking out the dancefloor rhythms, which left behind this kind of shell. A lot of the clubs in Europe in the Nineties had ambient rooms, with beanbags and tables, where you could go and just vibe.”

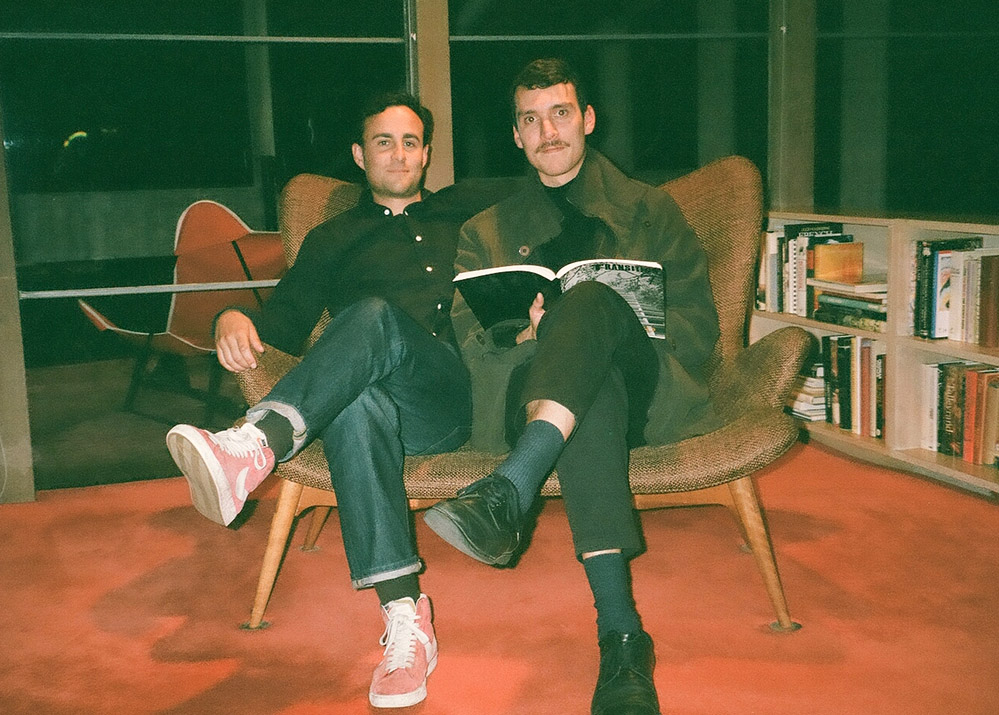

Sean La’Brooy and Alex Albrecht say Australia’s ambient music scene is taking off. (Credit: Albrecht La’Brooy*)

Of course, there isn’t just one kind of ambient sound. Just as there isn’t one kind of rock or one kind of metal. The genre has splintered over the years, as genres do, into sub-genres and sub-sub-genres, some of which are as far removed from Airports as Airports was from mainstream Seventies pop. “There’s ambient drum’n’bass, downtempo, drone music, that more industrial sound,” says Albrecht. “You can even have extremely fast ambient music. Our latest album is technically ambient, but it’s very heavy, dense, and big-sounding. Ambient means different things to different people.”

“There’s no doubt that Australian ambient music is having a moment in the sun,” agrees La’Brooy. “It was always this rite of passage for electronica artists, you know, you have to release an ambient album. But now we’re seeing labels putting out some really great stuff. Names like Music Company, OTIS Records in Sydney, Bedroom Suck, and JPEG Artefacts. Some of these guys are new, and others are established labels that are starting to dabble in ambient. It’s a really exciting time.”

“There’s no doubt that Australian ambient music is having a moment in the sun.”

One thing you find on many ambient tracks—particularly YouTube’s lo-fi chillhop, where animated girls scribble endlessly in notebooks and marmalade cats doze in the sun—is nature sampling. Raindrops on glass. Wind across water. Bird song and forest sounds. It’s something La’Brooy and Albrecht have done on their latest album, Healesville: a five-track ambient LP that practically massages your frontal lobe.

The boys moved into a mud-brick hut in the middle of a strawberry field, stocked it with two pianos and a Waldorf, and just jammed for days, drinking wine and cooking their own meals. “We had microphones hanging out the window the entire time we were playing,” says Albrecht. “During one of the sessions, a harvest was taking place, and you can hear tractors passing and workers laughing in the recording.”

“There’s no tangible way to play the sound of a strawberry field,” La’Brooy says. “But with a lot of our music, we look to external sources for inspiration. We’ve always had this affinity with nature.”

This is where ambient music sort of bleeds into nature recordings. The genres often get layered and confused and sampled together. Ambient allows your thoughts to blob and lava-lamp their way through the conscious mind. Or as La’Brooy puts it, to “create a heightened sense of awareness of your surroundings”. Wildlife soundscapes can do the same basic thing. But for some nature purists, it’s not that simple.

“Ambient music is like sitting down on the spot,” says sound recordist Andrew Skeoch. “It may not have much of a rhythm at all. It’s more like breathing. It sets up this sonic pattern that resonates with you. But here’s the difference: nature has no rhythm, you can’t tap your foot to nature.”

Skeoch started his own label, Listening Earth, nearly 30 years ago. The original goal was to create ambient music that synched with the environment—to somehow reconcile nature and Nord. “At one point we were outselling Slim Dusty!” he says. “But I felt most ambient recordings didn’t have that intimate connection with the natural world. It was all tech synth washes with some nature sounds glued on. There wasn’t a kinship there. The music side of things sounded flat as a tack. And I realised I’m not a good musician, but I do know how to listen to nature.”

Listening Earth has released over 100 albums of nature sounds, recorded in forests and deserts and wetlands all over the world. They usually involve Skeoch crawling through the undergrowth with a state-of-the-art, bi-aural, 360-degree recording rig. “It gives you this beautiful sense of space. You can almost reach out and touch the sounds,” he says. Skeoch sets his gear up in certain “sweet spots”—watering holes, gulley lines, the places where hunting trails cross—then leaves it for hours with the red light blinking. The rest is serendipity. Some days you’ll hear nothing but wind scouring the mic, other times you strike ambient gold. “Occasionally it’s like, ‘Oh my god! I’ve got a trio of brolgas and I can hear their feet on the ground,” he says.

Skeoch is quick to make a distinction between Listening Earth and the modern ambient scene. These aren’t ambient recordings, he insists, they’re wildlife soundscapes. “Music and nature sounds are two completely different languages. They’re processed in the brain in different places. Both are great on their own, but they don’t work together. It’s like playing Mozart and Mohler at the same time.”

Not all ambient artists would agree. “The beauty of ambient is it borrows from everywhere,” La’Brooy says. “You get elements of electronic music, the instrumentation and synths and drum machines, those sci-fi kind of sounds, but also the language of jazz, the harmonies and major sevens, that spontaneous improvisation. Nature is just another language artists can use.”

Of course, none of this really matters to the average music fan using ambient to sleep, or concentrate, or just vibe at a festival. In fact, this is one of the big challenges facing the ambient scene: people’s experience of live music helps grow the culture that surrounds it. And on first glance, ambient doesn’t lend itself to performance. There’s not much to see, for one thing—usually just a DJ and a synth machine. But more and more venues are slowly getting onboard.

Rainbow Serpent has had a dedicated Chill Stage for years, which plays arguably the most low-energy gigs on the planet, and Melbourne’s Substation hosted a dedicated ambient festival, ONO, back in 2017, which promised to “bring your imagination on an excursion into outer sound.” (To be fair, it’s descriptions like ‘outer sound’ that cause some critics to label ambient music high-brow audio wank. But as Eno himself said, “People dismiss ambient music, don’t they? They call it ‘easy listening’, as if to suggest that it should be hard to listen to.”).

“We’ve actually been to ambient shows where people fall asleep,” says Albrecht. “But that’s the beauty of the genre. Ambient music is the environment. It’s the sound around you. You can engage with it any way you want.”