Photograph by Lisa Johnson Rock

Tana Douglas: Meet Australia’s First Female Road Warrior

Born in Australia, Tana Douglas is a trailblazer. The first female roadie, a leader in a man’s world.

The work of a roadie is never done and rarely seen. Without their efforts, there’s no show. Recount the name of one roadie, just one, and you’re ahead of the game. And if you’re going to stop at one, make sure the name is Tana Douglas.

Born in Australia, Tana Douglas is a trailblazer. The first female roadie, a leader in a man’s world. A rock star among roadies having toured the globe with the likes of AC/DC, Iggy Pop, The Who, The Police and many more.

Rolling Stone caught up with Douglas for a Zoom chat from her home in the United States.

Fittingly, in some parts of her adopted homeland, Douglas rhymes with badass. “You’ve got to pick your battles. And still females in the industry today are picking their battles. It’s not just across the music business, it’s most careers,” she explains. “Still, we haven’t come as far as we think we have, and I think that’s unfortunate.”

Those battles were always hard fought. From a young age, Douglas set out to assemble an armoury that covered it all, front of house, lights, sound, action. She coupled her swag of skills with a thick skin and shotgun for a mouth.

“I developed a rather wry wit and a rather caustic tongue. I could pretty much cut them down to size with a one liner, and then smile and walk away, and everyone would laugh at them. It was a free-for-all back in the early days. Everyone was fighting to be there. But as a female, you really had to nip it in the bud. You couldn’t let it start.”

It also helps that she towers over many of the artists and crew she’s worked with. Standing just shy of six-feet tall, Douglas is “statuesque, she’s imposing and she’s strong,” recounts C, another experienced female roadie who admits to being in awe of her achievements. “Many, many times, I was the only woman for quite some time working on a gig,” handling general crew work, mainly lighting, rigging, setting up concerts, “but I’m not highly accomplished the way Tana is. There’d be no mistaking Tana.”

Like Douglas, C, who chooses to keep her name a secret for this Rolling Stone tale for reasons she declined to elaborate on, also worked and lived on three continents.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Putting the shoulder in with the boys, “sometimes I got very exhausted psychologically, trying to protect myself in a way. And I wanted to focus my energy more on doing the work I had to do rather than warding off behaviours,” says C. Some were either patronising, “‘Here honey, let me lift that for you’.”

Other situations felt like colleagues were putting her through her paces. “[They were] giving me jobs that were either slightly demeaning jobs they didn’t want to do or giving me jobs to test me out, and maybe even see if I failed. And I got exhausted by dealing with that.”

The nonsense ended when C cut her hair “super, super, super short.”

“It didn’t suit me in the least. And oddly enough, I felt that some of the guys accepted me more.” She also took the time to get to know the other halves. “If any other wives and girlfriends were at gigs, I’d befriend them. I just wanted to set aside any possible feelings of animosity. And also, I longed for some female company, sometimes, after working with all these guys.”

Douglas got a taste for rock ‘n’ roll early on. As a teenager, a “fifteen year old runaway from Brisbane,” is how she remembers it, she fled for Nimbin, a free-spirited hippie town in northern New South Wales, where the Aquarius Festival of the early Seventies famously opened minds, and planted the seed for a journey.

From there, inspiration and opportunities came from the most unlikely of sources — Philippe Petit, a French tightrope walker with a reputation for hair-raising stunts, came into her world.

Douglas would walk that fine line too, and it’d take her to the biggest stages, the mightiest tours of them all, and live on both sides of the Atlantic.

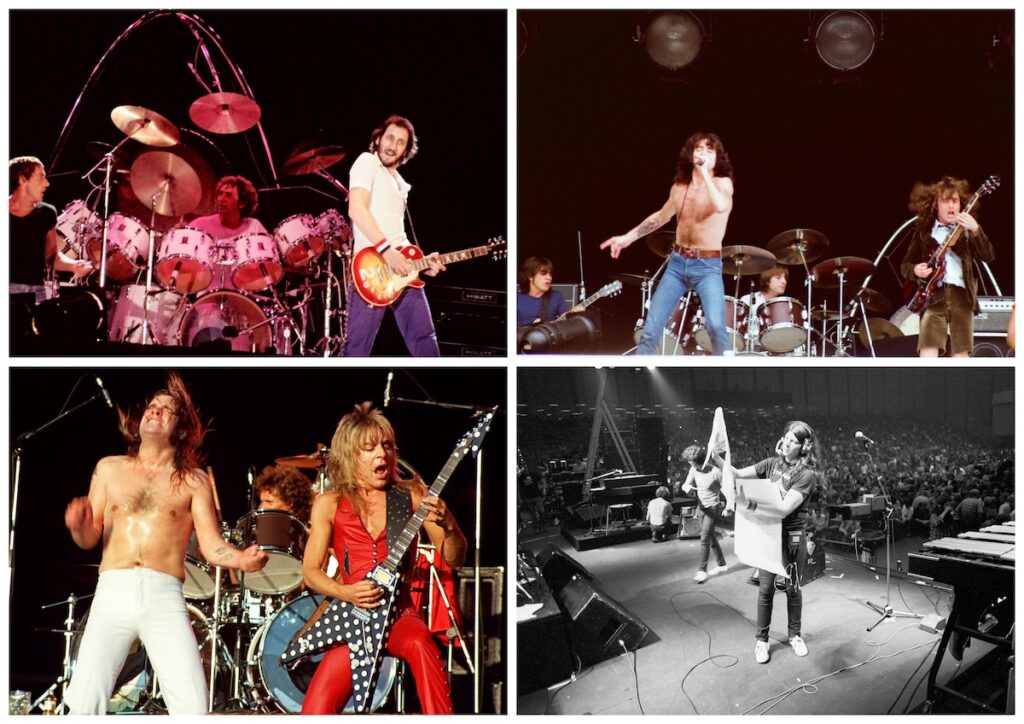

Douglas’ resume is a who’s who of rock royalty. The Who, AC/DC, Manfred Becker, and Ozzy Osbourne (clockwise from top left).

“The bottom line was, I was looking for a family unit. I was looking for somewhere where I could belong. And of all the places on the planet, you know, as they say, of all the joints and all the birds in the world, you walked into this one? Well, that’s what happened. I just wandered onto a stage one day and, it seemed to fit, and I found those sort of big brother types that would look after me. There were the smart alec ones that wanted nothing to do with me. But it was just like a big dysfunctional family, you know, and I never had a family. So I didn’t know how dysfunctional it was, I thought it was normal.”

All journeys have markers. Douglas’ was on August 18, 1979, when The Who played London’s Wembley Stadium. “I finally relaxed enough to know that I belonged.” Douglas had been asked to do the date, which turned into a tour. “You look at eighty-thousand people, and then just for a quick, brief moment, it was like, well, they’ve made it. I’m working for them, I’ve made it as well. It was kind of like a little piggy-back moment. My attitude changed after that job, or my perception changed after that, where I was more comfortable in my skin. And it didn’t hurt that AC/DC was on the bill as well.”

The Young brothers and AC/DC are more progressive than people give them credit for. The band’s career was, for many years, guided by Alberts CEO Fifa Riccobono, herself a trailblazer.

Back in the early Seventies, at a time when “a woman’s place was definitely not on the road, especially with a rock band,” Riccobono recounts to Rolling Stone, Douglas “managed to elbow her way into the ‘roadie’ slot” with the future Hall of Famers. She was sixteen, “a quick learner and gained the band’s respect and soon became the ‘go to’ person on the road.”

Douglas has her own theory. “I think that’s a family thing, that was ingrained with them,” she says of AC/DC. “They had strong women [around them], their mum was really strong, their sister was really strong. And so I think they accepted that and they look to it, you know, for guidance or comfort.” Having women in their inner circle was “really important for them,” she continues, “and I firmly believe that that’s probably the reason why I was offered the job.”

The job offers kept coming. Douglas worked with Ozzy Osbourne on his Blizzard of Ozz tour, she worked the Whitesnake tour in 1979 while pregnant (“nobody had noticed,” she explains in her autobiography), toured the world with Status Quo and wound up working with TASCO, one of the world’s biggest sound production companies. The globe and its stars of rock music opened up.

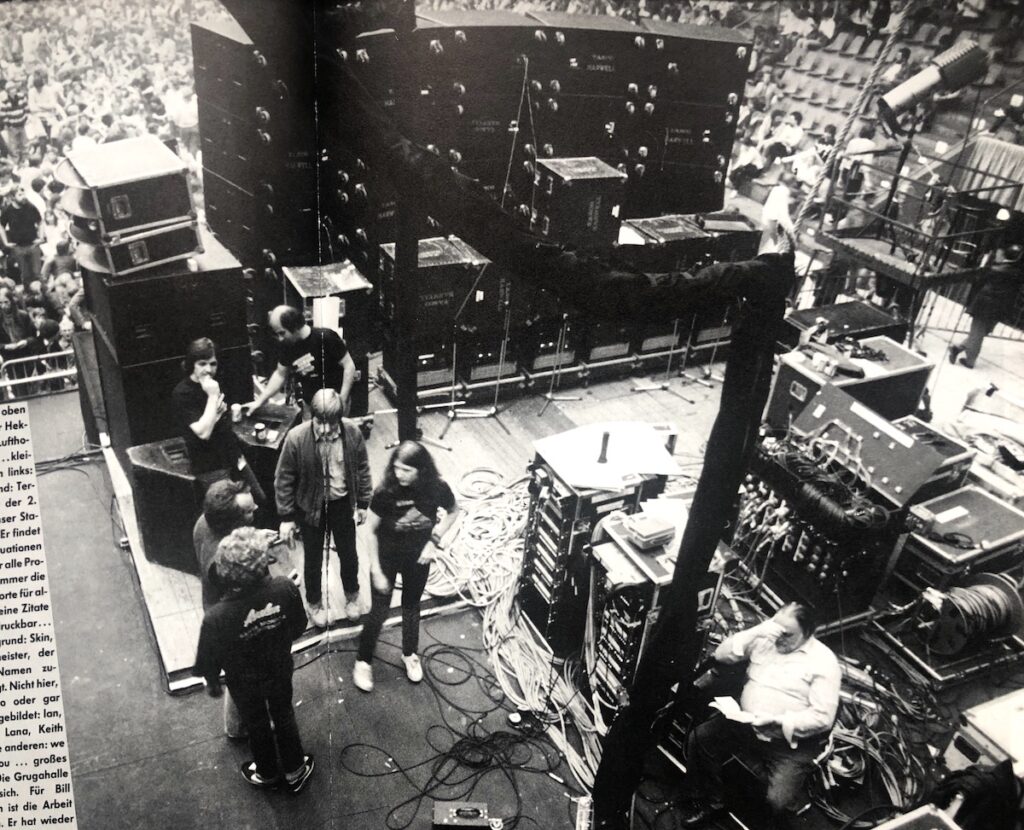

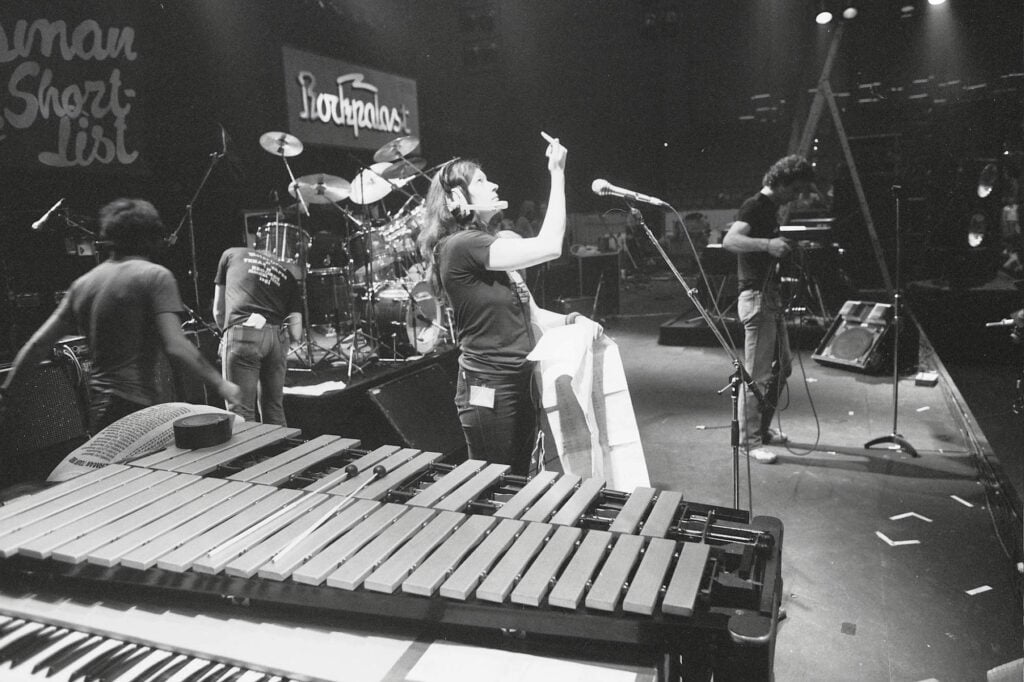

Tana Douglas at Rockpalast: With multiple headliner bands on the same bill, Tana would need to refocus the lighting rig between bands for WDR German TV (MANFRED BECKER)

With the benefit of hindsight, Douglas can identify the winning personality traits for a roadie. “Have a good rapport with people. It’s such an insulated existence. You have to have a personality where you have to be strong enough to survive, but you also have to be malleable enough to live in a little tin can flying down the freeway at one-hundred kilometres an hour, with twelve total strangers for the next eighteen months of your life. That doesn’t even count the bed (or lack thereof), or the local crews or the promoters or any of these hundreds of people who you’re probably never ever going to meet again.”

There was a time before professional roadies existed, as Stuart Coupe points out in his 2018 book, aptly titled Roadies. Back in the day, the artists or their closest would simply lug their own gear, a game that limits the stage and performance to something you’d see on Saturday night down your local.

Coupe’s tome opens with a study of Douglas and her achievements.

“Tana Douglas was a game changer. A pioneering woman — and a take-no-prisoners one — in the ultra male world of road crew,” he tells Rolling Stone. Coupe remembers his own “jaw dropping” when he asked Douglas her age when she was mixing AC/DC. “I was almost eighteen,” was her response.

Douglas was a fine sound person, something she’d learnt from her work without any formal training, notes Coupe in Roadies, published by Hachette Australia.

“You will never ever be as cool as Tana Douglas,” he says. “And that was just the beginning of an extraordinary career. She is totally the real deal.”

“You will never ever be as cool as Tana Douglas.”

Despite the many good times, she doesn’t attach herself to the memorabilia that collects over time.

Douglas recycles her gear. It’s a pattern, she says, recounting how she’d gather her goodies and head to Venice Beach, California where she would kit out the needy. Imagine, homeless people wandering around in Douglas’ preloved Pink Floyd and Elton John tour jackets, and you’ve got the glorious picture.

Imagine, homeless people wandering around in Douglas’ preloved Pink Floyd and Elton John tour jackets, and you’ve got the glorious picture.

Giving help is in her nature. Today, Douglas lends her time and energies to those organisations and companies which are “very female supportive”, through mentoring and guest speaking roles.

Douglas is clearly a one-off, though women remain a rarity in the twilight world of roadies.

A recently-published report into a parallel area of the music industry, the recording studio, found that men outnumber women and non-binary people by a ratio of nineteen to one on major commercial projects. The findings were captured in the 101-page Fix the Mix report, an initiative of US-based We Are Moving the Needle and Jaxsta, the Australia-based official music credits database.

“There’s women in the real world. Can we grow up and get on with it,” she explains. “We’re all alpha personalities, which is what makes us clash more. If we work together it’s so much easier.” Soundgirls (US), Women in Live Music (UK and Europe) and Australia’s CrewCare and SupportAct are among those organisations making a real difference, she says.

No story on the touring landscape can be told without a dabble with the dark side. Does the sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll stereotype still apply? Well, yes. “They’re just better at lying. Seriously, there’s so much money involved. They can’t admit to it,” she says of rock music’s long and storied alliance with substances. “People are still OD’ing, they’re just denying that they’re doing the drugs. To be fair, the drugs now are way more dangerous. I mean, I wouldn’t even consider doing any of the stuff that’s out there.” Having cast her mind back, “When I was in my twenties, did I ask what was in it? No,” she says with a laugh. “I don’t know the logic behind the whole drug industry at this point. It just seems to be to kill people. It used to be to have a good time.”

Change is slow, and Douglas has a front-row seat for some of the backwards legislation rolling out in some counties and states of the US.

“I did actually say to anyone in earshot that if Trump got in again (elected president in the 2024 federal election) I would leave. That’s it. If Trump’s in, I’m gone.”

And with that, Douglas considers the future. She still loves live music, and art; she studies art theory and fine arts at school. “They both tie in together,” she notes. She’s been pitched the idea of turning her life story into a screenplay. Those war stories, and there are many, aren’t for retelling. “Gossip on the bands? That’s not what I’m about. That’s not what the job is. It’s just as important that people find out what it is that we really do.”

“Gossip on the bands? That’s not what I’m about. That’s not what the job is. It’s just as important that people find out what it is that we really do.”

Douglas, who chronicled her life on the road in the 2021 autobiography Loud, is happily “semi-retired,” but another tour might work, in the right scenario. “I don’t want to go out there and be the grumpy old person on the tour. Am I gonna go out and unload trucks? Hell no. Give that to some kid in his twenties or thirties. There’s no need for me to be doing that. That’s just lunacy.”

Her body has, admittedly, held up well, her ears are in good nick (she thanks a career of wearing headsets), though her knees have taken some punishment. There’s a warning to all young roadies — don’t jump off the front of the stage. “I’m a pretty tough broad,” she admits. “Nothing’s brought me down yet.”

What next? Australia, perhaps. “Recently, I’ve been thinking, where do I want to go? A beach in Thailand sounds fabulous. But is that so practical? I don’t know. So why don’t I have the beach in Australia? For God’s sake, there’s plenty of them. I can actually see it happening. It’s probably the first time I’ve said it out loud.”