On a mild London morning in September, six musicians from the Gold Coast walked across the world’s most famous zebra crossing.

For most tourists, the entrance to Abbey Road Studios is a music lover’s ultimate photo-op; for Selve, it was a portal to making music history. Inside Studio Three of Abbey Road, where Pink Floyd cut Dark Side of the Moon and The Beatles bent pop into new dimensions, they were about to carve their own legacy as the first Aboriginal-led band to record a full-length album within those walls.

Loki Liddle, Selve’s frontman and a proud Jabirr Jabirr man, remembers the feeling as something beyond awe. “It was like flying through the eye of a needle,” he says. “We’re an independent band. No label, no safety net and yet, somehow, we were here. It was overwhelming… but we were ready.”

Released today (September 12th), almost exactly one year since its recording commenced, the story of Selve’s second album, Breaking Into Heaven, doesn’t begin with hallowed microphones or vintage tape decks. It begins in Broome, on Jabirr Jabirr Country, the land of Loki’s ancestors where he returned with Selve’s lead guitarist and proud Anaiwan man, Reece Bowden, to spend time with Loki’s relations, the land and the endless Kimberley skies.

The pair spent long days with Uncle Wayne Barker and Aunty Patricia Torres. Uncle Wayne had converted the community centre into a home studio, where the songs that would become Breaking Into Heaven first sparked to life. One of them, titled “Forever”, began as a stripped piano ballad — just Loki’s lyrics and Reece’s hands on the keys — but it carried an energy they instantly recognised as the heart of the record.

“My Jabirr Jabirr name is Joongabilbil — “the keeper of the fire”,” Loki explains. “Traditionally, Joongabilbil carried the embers from camp to camp in a coolamon [traditional carrying vessel], ensuring the fire never died. Approaching this album, my Aunty Pat told me that my embers were the Jabirr Jabirr spirit in my blood and the coolamons I keep them in are my songs, poems and stories. I kind of think of the album as one big coolamon and each song like an ember… My job is to keep them alive, to pass them on.”

That imagery threads throughout the album: the smouldering ember (“Mabu Walu”), the eruption into flame (“Mabu Walah”), the cyclical responsibility of carrying culture through time. For Loki, grounding the record in these words and stories wasn’t just symbolic, but essential. “Abbey Road has a hundred years of legacy,” he says. “But the stories I was carrying go back more than sixty thousand years.”

From Broome, Selve flew their coolamon of smouldering embers to a barn in rural France— the home of Midnight Special Records in the town of Noyen-sur-Seine— for a six-week writing residency. Picture the scene: baguettes, cheese, wine, weekend trips into Paris, and a circle of friends hammering out 25 demos in a converted farmhouse.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

More than just prolific, the time in France gave Selve a new creative process. Every morning the whole band — Loki, Reece, Creation Saffigna (BV’s/Lead Vocals), Liam Kirk (Keys), Michael Baldi (Drums), and Scott French (Guitar/Bass and producer) — gathered to ask a question passed down from Uncle Wayne: What are you risking?

“Because if you’re not risking something, you’re not putting your skin in the game,” explains Loki. “One day, that risk meant writing the loudest, most furious punk anthem we could muster. The next day, it meant something stripped and vulnerable, like ‘Catch My Breath’. Then we’d swing the other way again and write a love song like ‘Butterfly’ just to make the punks inside of us uncomfortable. Contradiction became our methodology.”

What emerged was an album stretching from post-punk to psych to pop ballads, threaded with orchestral flourishes and electronic touches. Loki toys with the term “prismatic rock.” “We’re defined by variety,” he says. “Each song is a different colour, refracted into a prism, but still reflecting the same light.”

When the time came to choose the final tracklist, chaos briefly replaced harmony. The “Great Selve Trials” saw each member of the travelling party submit their preferred songs, track order, even album titles. Votes were tallied. Disputes broke out. A “goose hat” and a “fraud stone” became part of the ritual and lore of album number two.

By the second day, one main song had divided the camp: “Breaking Into Heaven”. Some band members didn’t want it included at all. Loki went for a long walk by the Seine, headphones on, listening to all twenty-five demos in different sequences. That’s when his vision arrived.

“I saw a hand holding a brick against the blue sky,” he recalls. “I realised this record needed to be a brick through the window. Radical. Defiant. But the brick was also glass, refracting light, like Dark Side of the Moon. It wasn’t just destruction — it was a gift.” He came back, changed his vote, and convinced the others (sort of). The album now had a name, and a destiny.

The title draws from a Nina Simone quote: “The people that built their heaven on your land are telling you yours is in the sky.”

“To me, Breaking Into Heaven was about breaking into the central mythology of rock and roll,” Loki says. “Abbey Road is the nerve centre, the fortress. And here we were, First Nations artists, breaking in and planting our own story in that lineage.”

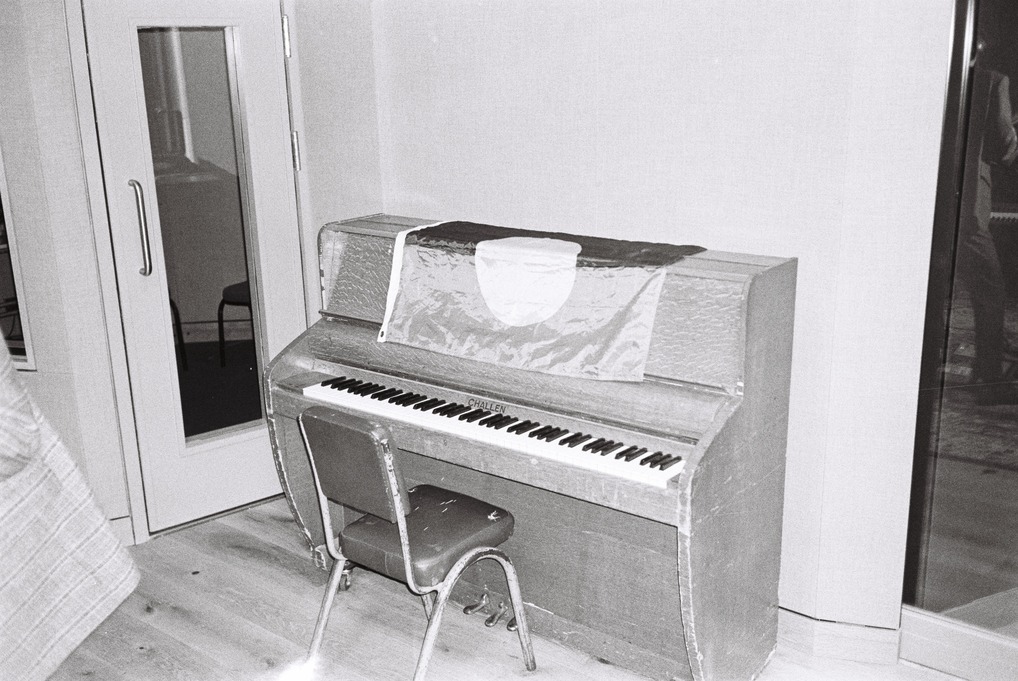

It was more than a metaphor. The Aboriginal flag was laid across John Lennon’s piano; lyrics like “Mabu Walu” — good fire, soft ember — were sung in a space that had never held those words before; and on September 24th, the band recorded “Butterfly”, a song written for Loki’s partner Creation and her late mother, whose name was also Butterfly, on what happened to be both Butterfly’s birthday and the birthdays of two other Selve collaborators, Reece and filmmaker Josh Tate. “Universal magic,” Loki calls it. “Impossible synchronicities everywhere.”

The band’s first visit to Studio Three on the eve of recording was overwhelming. “We collapsed onto the couch in tears,” recalls Loki. “It was too much. The ghosts, the pressure, the weight of it all. But by the next morning, we were charged up. We knew exactly what we had to do.”

For two weeks, Selve became the rare band to book the studio outright. “The staff at Abbey Road told us it hadn’t happened in years,” Loki says. “Most artists just drop in for a night to track vocals or drums. They were excited to see a band actually make an album there… Everyone was living their dream. I mean, obviously I drive the lyrical car, but everyone in the band had a field day with what they got to do recording-wise.

“The album was produced by Selve’s bassist Scott French (with co-producer Simon Benesch), who had an absolute field day in Abbey Road and was the full blown interstellar engine of the Selve mothership. With access to all the mics and instruments, we had a kind of jungle gym of sound going on. At one stage Giles Martin [son of Beatles producer George Martin] walked in, surveyed the studio, and said, ‘Wow, I haven’t seen it like this since back in the day.’”

With meticulous planning and a watertight schedule, the band recorded one song per day, starting with drummer Michael perched at a kit wired with £150,000 worth of vintage microphones. “It looked like he was in the Death Star,” Loki laughs. The engineers swapped out £50,000 vocal mics “like a toaster.” They played the original Mellotron from “Strawberry Fields Forever”; they played the same piano John Lennon used on “A Day in the Life” and even bantered with James McCartney in the studio gardens.

A pinnacle moment came when the band recorded “Forever” live in a single take, capturing an ember born on Jabirr Jabirr Country, fanned in France, now burning eternal on tape at Abbey Road. “That was the moment I felt my ancestors in the room,” Loki says. “It wasn’t just us making noise. It was carrying something much bigger.”

After months of surreal, painstakingly hard work, Breaking Into Heaven returned home with Selve from Abbey Road like a precious newborn, the question of “what now?” hanging heavy. They had a record, but no label, no marketing machine, no funding. “We were like, oh shit,” Loki admits. “Do we just frisbee it out into the universe and hope for the best?”

Instead, funding came through for what would become a game-changer: a visual campaign and a launch show as ambitious as the album itself. “We got lucky enough to get the resources,” says Loki, “which enabled us to create a really strong campaign and to have the climax be this huge debut of the album live at BLEACH Festival on the Gold Coast, where we played Breaking Into Heaven for the first time from start to finish, accompanied by the 33-piece Australian Session Orchestra.”

For Loki, whose writing is deeply informed by cinema, it wasn’t enough to simply put the record on stage. “I felt in my bones that the album deserved the most dramatic and over-the-top setting to be released into the world,” he says. With longtime collaborator Josh Tate, Loki ideated and co-directed five music videos. “Getting to take these songs, write the visual ideas, and actualise them was phenomenal,” he says. “Josh has a huge imagination and a super sensitive take on everything. Working with them was really beautiful.”

“It was also such an honour to collaborate with the deadly First Nations artists who cameod in our videos. We had Uncle Richard Bell as the Radical Commander of the ‘Breaking Into Heaven’ flying Academy and Charlee Fraser starring in ‘Leading Man Lost’. Charlee basically flew all the way from LA to play her version of me, that shoots another version of me, and takes over as Selve’s lead singer, strutting her stuff in a power-suit through the red carpets of a casino in our subversive take of a [2000 Fatboy Slim song] ‘Weapon of Choice’ meets [2018 Arctic Monkeys album] Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino style video.”

The live show folded all of it together: the orchestra, the videos, and a collaboration with Karul Projects, a contemporary Indigenous dance company led by Thomas E.S Kelly and Taree Sansbury. “That live launch featured the full band, an orchestra, the films we’d made, and visual dance works from Karul,” Loki recalls. “It created a whole other narrative around the album.”

Seven hundred people packed the theatre at the Gold Coast’s HOTA on August 1st for Selve’s biggest show to date. “To perform this album, that had already been such a huge and mind-blowing project, to a sold-out crowd with a freaking 33-piece orchestra, was out of this world,” Loki says. “We’d put so many string parts on this album during recording, so to hear them come to life felt like the record was reaching its full potential.”

Now armed with full orchestral charts, Selve plan to pitch the production to other festivals around the country. “We’d love to do a national tour, or at least hit some of the major Fringe Festivals,” Loki says. And for anyone who missed it, the performance was recorded and will be released as a live film alongside a Breaking Into Heaven documentary Loki and Josh are also co-directing.

Looking back, Loki shakes his head at the string of “pinch me” moments that have defined the project. “It’s hard to stay grounded when you keep flinging out the most audacious ideas into the world and people keep saying yes,” he laughs. “But it’s also a sign to dream big, and to try to make possible what people say is impossible.”

With the dust from BLEACH still settling, Selve aren’t slowing down.

Their upcoming Breaking Into Heaven tour takes the band across Australia’s east coast for a string of dates from now until November. They’ll join Winston Surfshirt and The Delta Riggs on the road, before stepping onto the Lost Paradise stage alongside Underworld to finish off 2025. For Loki, whose dad is a lifelong fan of the British electronic icons, it’s another “pinch me” moment in a year already full of them.

For now, though, Breaking Into Heaven is the fire they’re carrying forward. Loki leans on words that feel like both invitation and instruction: “First Nations music is the oldest music in the world. It deserves to be held in the same regard as any so-called classic.”

“We weren’t supposed to be at Abbey Road until we were. And I hope other mob see that and know you don’t need permission. Break in. Kick the gate down. Break into heaven.”

Selve’s Breaking Into Heaven is out now.

Selve wish to thank the following:

Special thanks to Uncle Wayne Barker & Aunty Patricia Torres for giving this album its true north.

To Thomas Briggs for engineering the album in the studio at Abbey Road.

To Josh Tate for bringing it all to screen.

To Ellery Burgett, Keilyn Waters & Clare Neal for keeping us well fed on a hectic schedule so we could focus on the work at hand.

To Creative Australia, Arts QLD and Experience Gold Coast for funding this project.