There’s no perfect way to describe the gloriously gloomy music of Rowland S. Howard, the slender guitar slinger whose dusky disposition was deeply imprinted onto the music of his bands — the Birthday Party, Crime and the City Solution, and These Immortal Souls —and his own solo recordings.

“The color of Rowland Howard’s music is a deep-purple bruise,” says Lydia Lunch, who collaborated with Howard several times.

“His guitar playing was like the stab of a switchblade,” says Against Me! frontwoman Laura Jane Grace, one of the many musicians he inspired.

Whether he was churning out carnival-calliope riffs or channeling sheer squalling feedback, there was an unidentifiable dark sensibility to his playing. His sound was so otherworldly that it sometimes sounded like his guitar was shuddering — as though it had the chills.

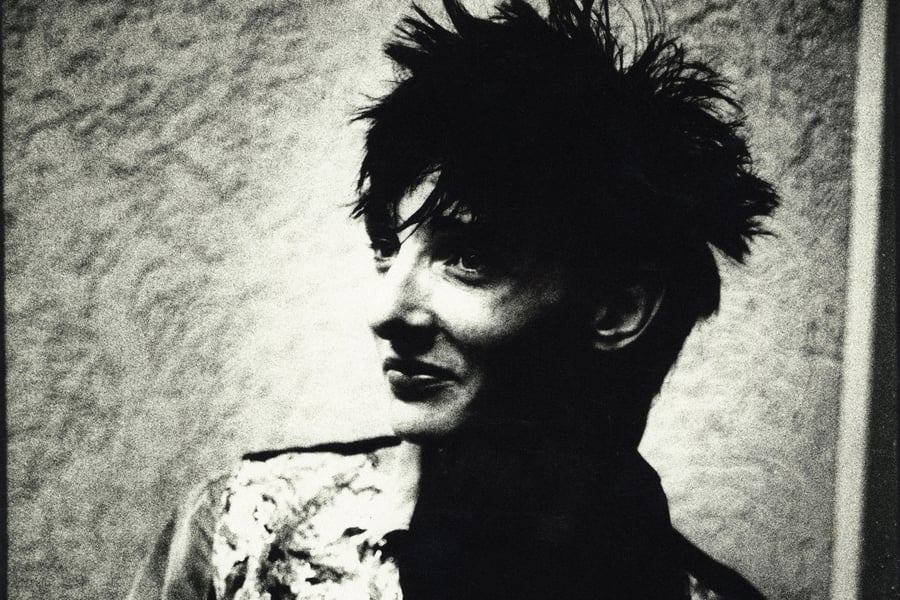

Since his death in 2009, the Melbourne-born guitarist has become something of a shadowy, rock-noir cult figure. It’s a role that suits him, partly because he looked the part. He was lanky and pasty with unkempt black hair, and his big, sad, doe-like eyes belied the terrors he coaxed from his instrument. He spent much of his life battling a heroin addiction, but his music almost always sounded sharp. Though Howard never achieved widespread recognition, his influence still reverberates through today’s dream pop, post-punk, and noise rock.

After his time with demolition-punk savages the Birthday Party, Howard’s body of work became more obscure. He played guitar in the gothic soul-punk group Crime and the City Solution, and he even sang in uneasy-listening combo These Immortal Souls. This was in addition to collaborations with No Wave doomsayer Lydia Lunch, ex–Swell Maps art-punk Nikki Sudden, a bizarre yet highly listenable album about Buffalo Bill with Jeremy Gluck, and innumerable one-offs.

Howard’s many projects are a lot to keep track of, especially considering some of his best work never got a wide release. But that’s been slowly changing. A few years back, his stunning swan song, Pop Crimes, finally came out in the U.S., and now his most singular work, the solo record Teenage Snuff Film, which many of his friends and collaborators say is his best album, is finally available in North America. The record originally came out in Australia in 1999 and contains songs that are both gorgeously morose (“Autoluminescent”) and jaw-droppingly melancholy (“Sleep Alone”). Now that more than a decade has passed since Howard’s death, people are still discovering his talent.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

After first picking up the saxophone as a kid, Rowland Stuart Howard shifted his attention to guitar as a teen and developed a unique style. It was equal parts surf-rock wipeout, eardrum-shattering screeches, sleazy twang, and dive-bombing belligerence. His tone was gaunt and shrill. Using only basic gear, he zeroed in on a guitar sound that could cut straight through a crowd like an arrow. On the live recording of the Birthday Party’s “Zoo-Music Girl” that appears on the 1981 live recording featured on Drunk on the Pope’s Blood, his riffs perform a jittering St. Vitus’ dance dance around frontman Nick Cave’s howling; on “Sleep Alone,” the final song on Teenage Snuff Film, he alternates between piercing leads and floating textures. Listening to these, it’s no surprise that Cave titled one song he and Howard wrote together “Six Strings That Drew Blood.”

“I think he just found noise really satisfying, personally,” says Rowland’s brother Harry Howard, who played bass in Crime and the City Solution and These Immortal Souls. “Rowland wasn’t very good at expressing anger in his personal life. I think it gave him a way to be quite aggressive and to scream publicly. He also just liked obscure sounds.”

“Feedback probably just came from the volume he was playing at, and he just accepted it,” says Mick Harvey, who played with Howard in the Birthday Party, Crime and the City Solution, and his various solo works. “It was part of the aural damage that he could create. He probably just chose to enjoy it; he certainly never worried about it.”

But his style extended beyond playing guitar. Although he often aligned himself with charismatic singers like Cave and Crime and the City Solution’s Simon Bonney, he was a perfectly capable frontman himself, and he had a style of singing that uniquely complemented his music. His voice was deep and sullen. Depending on the song, Howard was either a lounge singer from hell (or maybe one stuck in purgatory) or the unreliable narrator of the end times. He also had a scabrous wit that sometimes got lost in the mix.

He opens Teenage Snuff Film’s “Dead Radio” with the couplet, “You’re bad for me like cigarettes/But I haven’t sucked enough of you yet,” and professes, “When the lighting is bad, I’m the man with the most.” And those aren’t even the song’s cleverest lyrics; that honor goes to “I’ve lost the power I had to distinguish between what to ignite and what to extinguish.” “I would trade 30 of my songs to have written that lyric,” Laura Jane Grace says. For as self-deprecating as Howard’s words are, their sentiment is also oddly endearing.

Both his guitar playing and lyrical skill got a precocious start in a punk group called the Young Charlatans, for which he wrote the song “Shivers.” “I’ve been contemplating suicide,” goes the opening line, “but it doesn’t really suit my style.” The track was raucous and sardonic, with raw Johnny Thunders underpinnings, but it had an innate catchiness. When Howard’s next band, the Boys Next Door, recorded it, Nick Cave turned it into a sincere, sensitive ballad. In recent years, Cave has been playing it solo with a piano at his question-and-answer shows in tribute to Howard, and Against Me! have restored its punkness.

“Could you imagine writing that song when you’re 16?” Grace says. “I play that song at soundcheck a lot because I love the way the opening line will 100 percent always stop every person in the room dead in their tracks. It is that arresting. There is no heavier opening line in rock & roll.”

The Boys Next Door. From left: Rowland S. Howard, Mick Harvey, Nick Cave, Tracy Pew, and Phill Calvert.

Photo by GAB Archive/Redferns/Getty Images

Howard would hardly ever play anything so gentle again, as the band rebranded itself the Birthday Party (named, according to legend, after a debauched memorial-party scene in Crime and Punishment that Cave had misremembered as being a birthday) and developed a more lethal attack.

Once they found their focus, the Birthday Party’s musical power came from the way Tracy Pew’s brawny, Herculean bass lines fused themselves to Nick Cave’s brainy tableaus of terror. But their secret weapon was how Howard’s tinny, hollow riffs wove spider webs around the carnage.

By Cave’s estimation, the group first found its essence on “King Ink,” a lurching, menacing track that he and Howard wrote for their debut album, 1981’s Prayers on Fire. Howard’s guitar alternates from seismic waves of distortion to a pointy do-si-do with the rhythm section, as Cave suffers a meltdown, screeching lyrics about feeling like a bug swimming in a soup bowl. “I remember listening to it with Rowland Howard and going, ‘Look. Something’s going on here that’s really important,’” Cave once said. “I think we’d finally arrived at something that was unique. Before that, I think our songs were a mishmash of other people’s songs.”

Howard later groused about how the U.K. press seemed to think the Birthday Party, which moved from Australia to the Great Britain early on, were rip-off artists. “For the first two years the Birthday Party were in England, we were seen as being derivative of all these other groups,” he told Spin in 1986. “Then all of a sudden we were this really original band.” What’s interesting, though, is how none of Howard’s projects seemed to reflect his root influences.

Where the Birthday Party were, perhaps unfairly, compared to Captain Beefheart and the Pop Group, Howard took inspiration from more unusual places. His earliest idols, according to his brother, were Mick Ronson, who played guitar with David Bowie, and Roxy Music’s Phil Manzanera. Later, with the advent of punk, he became a fan of Clash and Public Image Ltd. guitarist Keith Levene; the New York Dolls’ Johnny Thunders; and Robert Quine, who played with Richard Hell and another one of Howard’s biggest inspirations, Lou Reed. He loved the harmony and discord of Television’s Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine and the raw power of the Stooges’ James Williamson.

“He really built his own sound in the first year after he joined the band, so by the end of ’79 it was pretty much in place,” Harvey says. “When we were in Europe, playing as the Birthday Party, he’d worked out his sound. I can hear aspects of his style on [the Boys Next Doors’ late-’79 EP] Hee-Haw.”

“I’d go back to ‘The Hair Shirt,’” Harry says, referring to a raucous song on Hee-Haw with a propulsive rhythm and Rowland’s jutting guitar attack. “That’s lyrically violent and it’s got a whole lot of noise guitar. It’s an insanely good song. But I’m not sure where it started, because Rowland was always stylish, and he was always precocious in his style.”

After the Birthday Party broke up over creative differences, Howard spent the next quarter century refining his approach but never really abandoning its core elements. With Crime and the City Solution, he performed the audio equivalent to atmospheric action-painting over Harry’s bass playing and Harvey’s drums. With These Immortal Souls, he presaged the surfer-cool aesthetic David Lynch milked on Twin Peaks. On his collaboration with ex–Swell Maps singer Nikki Sudden, he spanned blues strumming and lighting-strike lead lines for a stark, jagged sound, and with former Teenage Jesus and the Jerks frontwoman Lydia Lunch, he summoned new shades of glumness in a jarring rendition of Lee Hazlewood and Nancy Sinatra’s “Some Velvet Morning” and swampy blues on their Shotgun Wedding collaboration. His solo work was a mixture of bleakness and hope.

This versatility, coupled with the fact that he played with so many groups, is part of what makes his talent so hard to track. He was a guitarist who could convincingly interpret both the Stooges and Billy Idol and make them each sound like his own. But since many of his works aren’t immediately available to stream, his legacy has been pushed further into obscurity.

When people first hear the music Howard recorded after the Birthday Party now, it’s usually through a friend. And in the case of Laura Jane Grace, her world opened when she finally was introduced to it. “I was turned on to [Teenage Snuff Film] in 2013 when [Against Me!] were on the Big Day Out Tour in Australia,” she remembers. “A friend was almost offended I’d never heard it. Rightfully so.”

Because Teenage Snuff Film has been so difficult to find and because it was released to little fanfare, the record has attracted its cult following slowly. But thanks to artists like Grace and Courtney Barnett singing the LP’s praises, it’s had a surprising reach.

Howard began work on the album shortly after the disbandment of These Immortal Souls. He assessed the unrecorded songs he had, wrote some new ones, and connected with Brian Hooper, the bassist from Beasts of Bourbon who died in 2018, to come up with a couple of others for Teenage Snuff Film. He decided to keep things minimal, so the only other musician he reached out to initially was Harvey, who was surprised to hear from him.

After the Birthday Party, Harvey had joined Nick Cave’s new group, the Bad Seeds, a move he feels Howard resented. “I think he felt quite left out,” Harvey says. “I think he wrongly felt we continued the band without him.” But it was Harvey who suggested Howard link up with Simon Bonney and him in Crime and the City Solution. More discontentment followed when the lineup splintered, and the Howards formed These Immortal Souls while Bonney and Harvey continued with Crime.

“I think he harbored issues that he didn’t talk to me about openly,” Harvey says with a sigh. “I wish he had because I would have been able to explain my position on things that I felt he had taken the wrong way.

“When we did Teenage Snuff Film,” Harvey continues, “he told me he’d always loved the way I played drums, and he was quite surprised when I said yes to playing with him — if that describes anything about what he thought our friendship was. There were difficulties to the end. But without him here to have that argument, I’d rather not say more.”

In the years since the Birthday Party’s breakup, Howard had had trouble kicking his heroin addiction, but for Teenage Snuff Film, he was in relatively good shape. Although Harvey recalled Howard still using the drug “quite a bit,” the guitarist was undergoing an experimental treatment for his addiction called naltrexone. “It did actually work for a few weeks,” Harvey says. “He took it strategically, a week or so before we began the recording. What that meant for the recording was that his singing was really on. He wasn’t singing under the effects of whatever it is heroin does to your vocal cords, which is not conducive to accurate pitching. His voice was stronger. That album has the best singing he’s done.”

“Rowly was feeling good,” remembers Lindsay Gravina, who produced Teenage Snuff Film. “He’d just started his treatment regime, and Mick even remarked that Rowly almost seemed ‘sprightly’ compared to his usual sullen self. He even was able to stay back late with me on several occasions — most of the recording of that album involved just the two of us, with the occasional visits from people.”

The producer remembers the sessions as surprisingly easygoing. Harvey would listen to a song for the first time and come up with a drum part in one or two takes. Gravina recently dug up a version of “Shivers” that they cut at the time, with vibraphones on it, but never released; Harvey told Gravina he thought it was the best rendition of the song. Mostly, though, they worked intensely on crafting the right feel for the record.

Teenage Snuff Film shifts with ease from downtempo rock to aural assaults. There are delicate, orchestral strings and enough space for Howard’s guitar to chime out blissfully on a song like the ballad “Autoluminescent.” He has the nerve to cover both “She Cried” (putting his spin on the arrangement the Shangri-La’s used on their rendition, retitled “He Cried”) and Billy Idol’s “White Wedding,” which shows off his sharp sense of humor with its dusty, folk-rock arrangement. (“He took a perverse kind of pleasure, I think, in taking a song that no one would dream he would do and imbuing it with his ‘Rowlandness,’” Gravina says.) But mostly, the album is 54 minutes of gloriously acute downer rock with a severe romantic streak. “Bind me to you, I don’t care what you do,” Howard sings on the waltzing “Silver Chain.”

“At one stage, Rowland said that he thought music should have everything in it,” Harry says. “It should be stupid, smart, funny, and serious. He wasn’t limiting himself in any way.”

“He was so romantic,” Lunch says. “He loved every woman that ever walked on the planet. He was really funny. People don’t get that because his music was so intense and dark. But he was a chuckle fucker. He loved to laugh.”

Grace has called Teenage Snuff Film her all-time favorite album, one that made her a “Rowland S. Howard loyalist.” “[Teenage Snuff Film] is a perfect album from such an underdog; like the ultimate underdog fuck-up,” she says. “He is realizing and admitting to how much he regrets the ruin of his life through these songs. It’s all laments. … I’ve just never heard a more honest recording of walking death. He knows he’s dying, there’s no getting out of it, but it’s not resignation or fear that he’s feeling yet. It’s not sadness or self-pity; it’s ice-cold rage channeled into every chord and every word. It’s so vivid and eternal. You can close your eyes and feel it all.”

“The challenge for ‘Sleep Alone,’” Gravina says, referring to the record’s knockout closing song, “was how do I get everything to sound ‘apocalyptic’? I got Rowly to do a few different takes of the guitar and blended together the best bits for maximum mayhem. The noise bit at the end is pure genius and was one take. I insisted we keep the very end, which is an unintentional wisp of noise that might have been left out, except that it sounded like the last gasping breath from a dying beast. Ironically, this was the track that was played at Rowly’s funeral as they were carrying out his casket.”

Ten years later, the same team reunited with a few fresh faces to record the album that would be Howard’s swan song, the solo release Pop Crimes. The tone was still typically drab, but it’s a little looser and less claustrophobic than Teenage Snuff Film. “Rowland was quite sick when making Pop Crimes, and obviously more ill than we all thought,” Gravina says. “Many sessions were canceled at the last minute if he didn’t feel strong enough to attend. When he did, the sessions were often quite short, just a few hours. Often Rowland took naps midsession, so it was hard to get any work done. There was less of that seething misanthropic anger, and more of a tone of resignation, and maybe mortality. It was always going to be a different record compared to Teenage Snuff Film, certainly more vulnerable, but still has that emotional clarity.”

The album came out in October 2009, and within two months, Howard had died of liver cancer and liver cirrhosis, hastened by years of addiction. He was only 50.

In the years since his death, Rowland S. Howard’s friends and family have worked hard to preserve his legacy. Harvey led a group of musicians through a number of songs from Howard’s oeuvre at a tribute concert that was part of the All Tomorrow’s Parties festival in Australia in 2013. And earlier this year, they revived the concerts in Paris and London, where Harvey, Harry Howard, Lydia Lunch, These Immortal Souls’ Genevieve McGuckin, Nick Cave, and others sang his songs again. Both Harvey and Harry hope to bring the tribute to the States at some point, depending on the various artists’ schedules and budgetary needs.

Harry thinks the reason his brother’s music didn’t become a smash success in the States is because of the Birthday Party’s relatively minor impact in North America, where they only toured twice. He and the others, though, are excited to see his releases, and Teenage Snuff Film in particular, finally get their due.

“He found a way to express devastating emotions,” Harry says. “He was just letting stuff out. He was a very passive person in real life. He was quite stubborn and could be arrogant and he wasn’t always nice or anything like that, but basically, he was very gentlemanly. But musically, he could be really brutal and create devastation before your eyes.”

“I could never understand the naysayers, the people that said I was wasting my time, that he was washed up and finished as an artist,” Gravina says. “I’m just glad that the album [Teenage Snuff Film] got released. Obviously, it has finally been accorded some kind of cult status and is a much-loved album, but back then no one wanted to know about it. Financially, Bruce Milne, who put the record out, and myself both took a hit, but those are the hits you are always willing to take. Because it’s art.”

“His music was just so majestic,” Lunch says. “It’s like every note mattered. It was so ethereal, and it was so beautiful, and it was so unique. I mean, every group Rowland was in, whether Crime and the City Solution, These Immortal Souls, or his solo records — Teenage Snuff Film is one of my favorite records — the beauty, the majesty, the magicality of it was always there. You could always tell it was him playing.”