Elvis Presley had been dead for six months when the plastic-surgeon’s knife plunged into Dennis Wise. There Wise lay, on a table in an Orlando hospital, surrounded by photos of the King. He knew what was coming, but the reality of it didn’t really hit him until the doctor, who seemed like a nice enough guy, started carving into his face. “All of a sudden, it started hurting real bad,” Wise recalls. “He said, ‘Give me something!’ and a nurse came over and plunged this needle into me.” Wise soon went under.

When he woke up, his swollen face wrapped in bandages, Wise had implants in his cheeks and a curled-up lip, and he was on his way to resembling the King more than his 23-year-old self. For the first and not last time, his boss, Danny O’Day, could boast, with one of his robust laughs, that he was “the monster maker.”

In pop music, the tradition of the tribute band, the imitator, the impersonator, is now as durable as the concert T-shirt or the demand for an encore. As far back as the Seventies, touring and club acts meticulously did their best to look and sound like the Doors or the very much alive Bruce Springsteen, and tourists in Manhattan flocked to Beatlemania, a Fab Four tribute that ran on Broadway for two years. To this day, you can easily see tributes to ABBA, Rush, or Eighties and Nineties hip-hop. The new-tech twist is the hologram, which has brought Michael Jackson, 2Pac, Frank Zappa, and Whitney Houston back to a semblance of life.

Impersonating a dead pop star, or reviving them virtually, is one thing. But more than 40 years ago, Danny O’Day took imitation to a place no one imagined before or since. Rock and Roll Heaven, the touring extravaganza he conceived and promoted, didn’t just pay homage to one deceased icon, but four of them: Elvis, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, and Jim Croce. And it didn’t do it merely with costumes or note-for-note vocal imitations: O’Day hired plastic surgeons to physically alter his tribute singers to look as much as possible like the people they were honoring. “Jesus Christ — that’s some twisted shit,” says Croce’s son A.J., who was only a grade schooler when O’Day hired an upstart to be resculpted as Croce’s father. “The first thing that comes to my mind is that plastic surgery is the highest form of flattery.”

“He was way ahead of the curve,” says Jeff Pezzuti, founder of Eyellusion, responsible for recent hologram tours of Frank Zappa and Dio. “It was very fresh at that point compared to now. Way before technology, there wasn’t anything else you could do.”

What O’Day himself dubbed his “clone army” only wound up fighting a few minor skirmishes: a handful of TV appearances, and gigs at clubs, state fairs, and casinos, earning enough notoriety to have possibly inspired not one but two Saturday Night Live parodies. (The first was a 1981 skit about a sleazy Rock and Roll Heaven marketing company, featuring Eddie Murphy, that made a joke about “the Three J’s — Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Croce.”) In 1978, the clone tour was cited in Rolling Stone’s year-end issue, under the header “The Brides of Funkenstein.” (“Two aspiring women performers underwent plastic surgery: one to look like a female Elvis; the other, Janis Joplin.”) But almost as soon as it arrived, Rock and Roll Heaven imploded, and O’Day became the smallest of footnotes in pop history books. A.J. Croce hadn’t heard of the tribute until contacted by Rolling Stone, and neither the Joplin estate nor the surviving members of the Doors remember these “clones” from more than 40 years ago.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

But long before Las Vegas residencies, biopics, and massive publishing buyout deals, O’Day imagined a world in which classic-rock nostalgia would be a lucrative business. He knew the time was coming when the bond between rock icons and fans would grow so intense that an industry could rise to exploit that union. “Once the artists are gone, they’re gone,” says Pezzuti. “And you have the fans who want to see that artist continue.”

O’Day would never be on the level of Colonel Tom Parker, but he was something else entirely — rock’s own P.T. Barnum, a man who could, in Wise’s words, “sell ice cream in hell.” If that meant hiring someone to turn living singers into facsimiles of deceased ones, so be it. “In this country, we always want what we can’t have,” O’Day once said. “Look how well records by dead rock stars sell. You don’t miss your water until the well runs dry. It’s America.”

To hear his family tell it, Danny Dixon O’Day could have been a star. Growing up in Baltimore, he played drums in a few local bands, and thanks to an unstable household — his mother had several husbands, according to a family member — the teenage O’Day left home for California, where he hustled his way into other bands. He wound up in one called the Flim Flam Band, where his future wife Effie saw him perform covers in her hometown of Ocala, Florida, in the early Seventies. With his sandy-brown hair, six-foot-plus height, and strong voice, O’Day had the goods: “He had talent, and he could play almost any instrument there was,” Effie recalls. The two married in 1974, and O’Day eventually adopted her two children from a previous marriage.

The Flim Flam Band continued working, in what O’Day’s cousin Paul Patten calls the “Howard Johnson’s tour” of lounges in those family-vacation hotels. By 1977, the band found itself gigging in Arkansas, doing what their guitarist Jim Wise calls “Stevie Wonder and disco stuff.” O’Day was also learning how to work the system. Wise heard a story — maybe apocryphal — that O’Day had booked pop star B.J. Thomas into a local club, took the money, and then disappeared; it turned out he didn’t actually rep Thomas at all. “Sounds right,” says Patten, laughing. “We called him the flim-flam man with the Flim Flam Band.”

By coincidence, Wise had a brother, Dennis, who knew how to sing like Elvis. Jim called Dennis, who was then selling Toyotas at a Honolulu dealership, and asked if he’d want to come to Arkansas and try out for their band. It was late 1977, Elvis had just died, and maybe there was a market for a tribute act. Dennis Wise sang “Trying to Get to You” for O’Day and the band, and O’Day told him that was all he needed to hear.

CBS Broadcasting

CBS Broadcasting

Dennis Wise thought that was the end of it all and he would return to Hawaii, but instead, O’Day asked him to meet at his hotel. There are disputes about what happened next. Wise says that, inspired by Dark Passage, the 1947 film in which Humphrey Bogart’s escaped-con character undergoes plastic surgery to avoid recapture, he suggested altering his face to look more like the King. “Danny was flabbergasted I said that,” says Wise. “You know that saying about a lightbulb going off over your head? It was not for money purposes. I wanted to be an entertainer, and who doesn’t want to be like Elvis — come on!”

Effie insists the idea was her late husband’s. “How would Danny come up with that?” she says. “I have no idea. It was such an odd thing. I was like, ‘What?’ But his mind worked that way. He would sit around talking about things like that.… He could visualize things happening or ways to promote them. He would say, ‘We ought to do this!’ and I would be, ‘Oh, my gosh!’”

O’Day already knew the limitations of tribute bands. He had previously wanted to manage a Barbra Streisand impersonator but soon realized the audience wouldn’t buy his first choice: At five feet two and 160 pounds, she didn’t conjure Streisand physically. He had to think outside the rock box, and maybe drastic measures were in order.

O’Day started by taking Wise to a Florida dentist, who shaved his teeth down to resemble Presley’s and closed up the gap in his two front teeth. Finding the right plastic surgeon to tweak Wise’s lips and cheeks and straighten his nose was tougher. O’Day’s first choice bailed when his name leaked to the press. O’Day scrambled and found a replacement after several tries. Eventually, O’Day was able to smuggle Wise into that clinic on that day in January 1978.

O’Day had what felt like a foolproof method of making the operation seem as routine as possible. “When I take these people in, they already have a basic resemblance to the person I want them to look like,” he said. “I just say, ‘I want plastic surgery done on her nose and his chin and this and that and, oh, by the way, I just happen to have a picture here of exactly what we want done.’” When the six-hour procedure was finished, Wise was rolled out in a wheelchair, his face covered in bandages. “There must have been 100 people from the press all over the world taking pictures,” he says. “It was amazing. They’re yelling at me, ‘How do you feel?’ ‘What are you thinking?’”

Wise says he didn’t tell anyone in his family, including his parents or brother, since he feared they would think he was nuts. But several weeks later, he made his post-surgery television debut on Good Morning America, and at press conferences began imitating Presley’s Southern drawl and polite use of “ma’am” and “sir.” His brother Jim watched one of his TV appearances in a bar. Jim wasn’t sure what to make of it, but he did see one upside. “Dennis got his nose broken when he was in the Marines,” he says. “Somebody hit him in the face and knocked him out. So the surgery was an improvement.”

Wise made his debut onstage so soon after the surgery that black rings still encircled his eyes. The novelty of the show, at a club in Melbourne, Florida, combined with all the press the surgery had received, commanded a rock-star-worthy fee — $15,000 for the first week (about $60,000 today). The first night, Wise was singing “Love Me Tender” and passing out scarves à la the King when a woman in the crowd came up and grabbed him in the crotch. “She wouldn’t let go,” he chuckles. “The guys in the band were all laughing.”

But for Wise, the jailhouse only rocked for so long. He says he and the band weren’t paid in full for their work. (“Blame it on the club owner,” O’Day said in response.) When Wise reexamined his contract at the time, he realized he’d signed with O’Day for 50 years and that O’Day was entitled to half his earnings. Wise trekked to O’Day’s home in Ocala, just in time to see his boss roll up, living large. “Danny pulls in with a brand-new Burt Reynolds Trans Am,” he says. “Guess where the money went?” Wise wound up suing O’Day for negligence (claiming his “professional reputation has been damaged”) and “breach of fiduciary duty,” demanding a minimum settlement of $2,500. Wise says he never saw a dime, nor ever saw O’Day again. But for O’Day, it probably didn’t matter: He already had a bigger, grander, and wilder scheme in mind.

Ramona Caywood — then Mona Caywood Moore — was playing bar gigs in Ohio, in a band called Stage Fright, when she received a call from a friend in the business. “He said this guy is putting together a show and they need a Janis Joplin,” Caywood recalls. Since Joplin imitators were rare back then, Caywood adds, “I was the only person who could do that at the time.”

Caywood, a native Californian who sang in a sassy rasp reminiscent of Joplin’s, didn’t know the full story. But once she arrived for the job, she realized what her new boss had in mind. O’Day’s experience with Wise may have ended badly, but it gave O’Day a taste of big-time showbiz, and he wanted more. What if, instead of one altered rocker, he had an all-star ensemble of them? “He did say, ‘Well, what can we do? Something nobody’s ever done before,’” recalls Effie. “Some people thought it was very bizarre, but people were interested in it from the standpoint of business.”

To make himself feel better about the idea, O’Day ran it by his mother: What if his younger brother, who’d passed away at 21, had been an entertainer and died and had been resurrected by way of plastic surgery? His mom said she’d be fine with it as long as it was done “in good taste,” and that was good enough for her son.

By 1978, Elvis wasn’t the only rock star in the grave; the body count was rising. Joplin had overdosed eight years before, and Caywood knew the repertoire well. Morrison had been found dead in a Paris bathtub seven years before. As it turned out, Duke O’Connell, the drummer in an O’Day-managed cover band called the Copycats, had been singing Doors songs in that group. Cram him into brown leather pants and he might pass for the Lizard King. Croce had perished in a plane crash in 1973, but Marc Hazebrouck, a former truck driver and psychology major from Rhode Island, was already playing songs by Croce and had a droopy mustache to match. Since Wise was persona non Presley in O’Day’s world, a new King was needed. O’Day heard about a local Florida band whose lead singer, Jesse Gamble (then Jesse Bolt), was a good Presley mimic, and even already owned a blue jumpsuit.

When O’Day proposed the idea of surgical transformation to them, the newly hired hands were either eager or puzzled, depending on the singer. “I just thought, ‘Well, I don’t know — what does that mean?’” says Gamble. “I was 30 or 32 and wild and crazy anyway. And I said, ‘Well, you know, I guess I could do something.’” Caywood was up for singing Joplin tunes: “I thought, ‘Cool, that sounds fun!’ I’m famous for picking up and moving my entire life. Sight unseen, always.” And just like O’Day, each was hungry for recognition and success, a very different type of American dream.

Once again, O’Day arranged for the operations, forked over the money (supposedly in the area of $500,000, partly from loans), and alerted the press. This time, the surgeries weren’t quite as invasive as they’d been with Wise. Hazebrouck’s lips were enlarged and lowered, and his straight hair was given a Croce-style perm. Bags were removed from under O’Connell’s eyes, and wrinkles from his cheeks. Caywood had a small implant in her chin “that just made it look a little more pointy — so minor, like outpatient stuff.”

Gamble had the most minimal work done: The surgeon basically made a cut above his lip to make it look as if he’d had surgery. “The idea was to say I was trying to develop the sneer, I guess,” he says. At Gamble’s suggestion, his girlfriend, a North Carolina native named Deborah (or Erin) Rhyne, had her nose straightened and hair dyed black to resemble a “female Elvis.” (“I’m going to be Elvis in the early 1950s, when he was feminine-looking,” she said.)

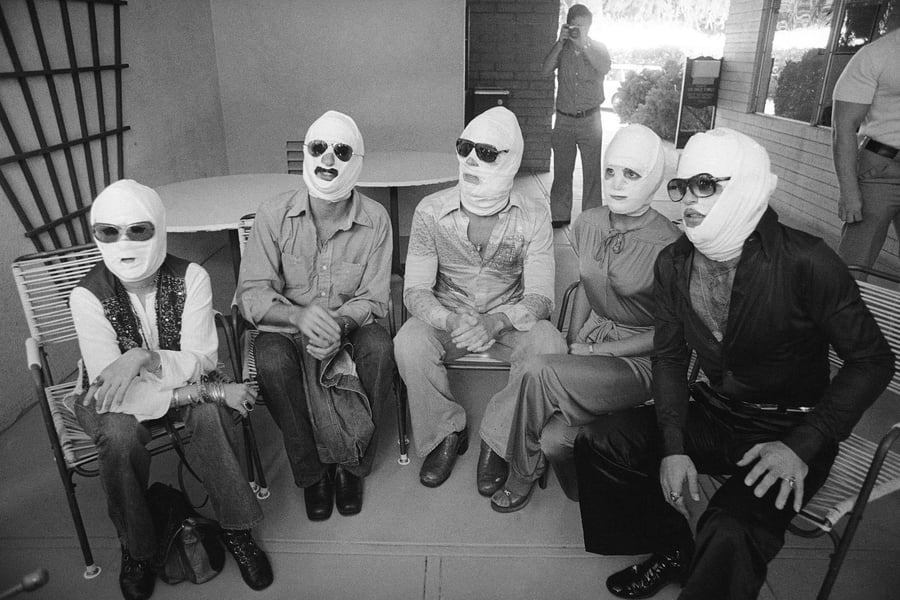

O’Day then arranged for the performers, still bandaged up and looking like mummies with large eyeholes, to be publicly unveiled on a network daytime show, America Alive! In fact, the clones didn’t need the bandages, but O’Day, ever the showman, insisted they keep the wraps on for maximum suspense. The results could be comical: Caywood recalls a drive when some of them were pulled over by cops, who thought the bandaged people in the van were thieves.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

The TV appearance was a mixed bag: Dr. Joyce Brothers, the star psychologist and talk-show regular, accused O’Day of being a Manson-style cult leader. But none of it gave O’Day even the slightest pause; by now, he was in full Barnum mode. At a hotel pool in Florida, an on-message O’Day introduced his clones to a writer from the Miami News and regaled the reporter with tales from his rock & roll crypt. In his mind, Rock and Roll Heaven would merely be the beginning. He talked about re-creating Buddy Holly, Jimi Hendrix, and the members of Lynyrd Skynyrd who’d died in a plane crash the year before. Then, he would move on to dead comedians, remaking people to resemble W.C. Fields and Abbott and Costello.

O’Day — who used the word “clone” while agreeing that that wasn’t quite the right scientific term for what he had paid doctors to do — even boasted he’d found a chemist in Los Angeles who could alter someone’s pigment. “I’ve got this kid who does a great Otis Redding, but he’s white,” he said straight-faced. “If it turns out [the chemist] can deliver the goods, then we’ll give the kid the pigment.” Hearing those comments again, Gamble sighs: “That sounds like sitting down and talking to him. It was like the stream of consciousness off the top of his head. He would just come out with that stuff, you know?”

Newspaper headline writers reveled in the weirdness of Rock and Roll Heaven, dubbing it “the cloneheads” and referring to O’Day as the “clone ranger.” O’Day brushed off any and all skepticism. “I don’t see a morbid aspect,” he said. “I would see a morbid aspect if we were being crassly commercial in cashing in on dead people. But all we’re doing is emulating the dead people with all due respect.”

Watching from afar as he attempted to revive his deflated career as a new Elvis, Dennis Wise had his worries. “What Danny is doing with his new idea is just not right,” he told the Miami News. “I would tell those people not to do it. They don’t know what they’re getting into.” But nothing would stop them, or O’Day.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Rock and Roll Heaven opened with the backup band playing an instrumental version of the Righteous Brothers’ dead-rocker hit of the same name. What followed was anything but conventional, even during an era, the Seventies, when genuine rock stars would pop up on campy network TV specials. The band shifted into “Also Sprach Zarathustra” (the theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey), the traditional orchestral opener for Presley’s shows, and Gamble, in full Elvis sunglasses and jumpsuit, welcomed everyone to the performance. “I forget the script,” Gamble says, “but it was Elvis coming down from heaven to bring back some friends.”

Often, the shows would start with O’Connell as Morrison, vamping through the Doors’ “Light My Fire,” “Love Me Two Times,” and “Touch Me,” before Hazebrouck came out with Croce hits like “Time in a Bottle” and “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown.” After a brief intermission, the band launched into a stomping groove, and Caywood stuck her hand through a curtain holding a bottle of Southern Comfort before emerging — “feathers flying,” she says — and starting her Joplin set, which included “Ball and Chain” and “Piece of My Heart.” Then, Gamble would re-enter, karate-chopping his way through a medley of Elvis hits, before everyone reconvened onstage for a grand finale. Dry-ice fog made a cameo, too.

Despite the media splash and countless articles that accompanied it, Rock and Roll Heaven didn’t exactly rock the house when it launched. At the tour’s debut, at the Southeastern Music Fair in Atlanta in September 1978, fewer than 50 people showed up. (O’Day bragged to a reporter that it was a “small but mighty” crowd.) “He didn’t like that, the state fairs,” says Effie. “But a lot of the nightclubs were afraid it was just a freak show. They didn’t know they were talented musicians.” In Miami, the tour was booked into the Persian Room at the Marco Polo Hotel, but when not enough tickets were apparently sold, it was downgraded to the Swingers Lounge Disco. “They were bombs, man,” says Caywood of the earliest, sparsely attended Rock and Roll Heaven shows. “We did a couple of state fairs where there were, like, four people in the audience.”

At an early stop on the tour, one reviewer noted that few of the performers resembled their dead counterparts that much. “If you can’t read the first three lines on an eye chart, then I suppose physically he might fool you,” he wrote of Croce, also pointing out that the clearest resemblance came by way of the band’s non-altered lead guitarist, a dead ringer for Peter Frampton. Caywood denies a report that she had her jaw restructured, which was likely more O’Day hype: When another reviewer pointed out that Caywood wasn’t a dead ringer, so to speak, for Joplin, O’Day claimed she would have further work done to counter the criticism.

Some of the performers had reservations about what they were doing. “Yeah, I thought, ‘Oh, this is so weird,’ many times,” Caywood says. “I’m impersonating her, but I was the same age she was when she died.” But some of that melted away when O’Day landed them a residency at Harrah’s in Lake Tahoe, followed by a similar stint at that same casino in Reno in the early months of 1979. It wasn’t Vegas, but it was close, and it came with perks, like all the alcohol and Perrier anyone wanted. In Reno, Gamble saw O’Day handing out five-dollar bills to people at the door to lure them inside. O’Day also landed them an appearance on Tom Snyder’s late-night network talk show.

Caywood was already “a fireball, get-out-of-my-fucking-way person,” as she says, with a bad-ass stare and freewheeling vibe to match. She’d previously worked in a health-food store, but for Rock and Roll Heaven, she developed a fleeting taste for Southern Comfort, Joplin’s drink of choice. “It was a Method-acting thing,” says Caywood. “When I found out I was going to do this, I said, ‘Well, enough of [health food],’ and I went out and had a cheeseburger with a shot of whiskey and beer.” To dispel any doubts about the actual alcohol in her onstage bottle, she’d pour some of it into the glasses of skeptical fans in the front rows, and watch as they gulped it down and realized they were drinking genuine Southern Comfort.

Gamble, a high-school dropout who’d worked as a carpenter and in local theater productions of musicals like Bye Bye Birdie, reveled in his Kingness. He recalls seeing cocaine backstage, and during a Tahoe drive, Gamble stocked his black Lincoln with a cooler of beer and some Jack Daniel’s — and was, of course, pulled over by cops for some infraction. Luckily, Gamble says, he was able to point to a Rock and Roll Heaven billboard with his face on it, and he got away with just a warning.

Ultimately, just as in the living-person rock business, money changed everything. According to Caywood and Gamble, no one was getting paid much, if anything at all, and what pay existed wasn’t always equal. “I feel weird saying this, but basically I was the hit of the show,” says Caywood. “And I wasn’t being paid anywhere near what ‘Jim Morrison’ was. It was just not right.” The Reno Gazette-Journal agreed, noting, “Caywood-Moore’s ‘Ball and Chain’ is a showstopper.”

As the Reno run began winding down, O’Day planned to take Rock and Roll Heaven to its natural destination: Las Vegas. But he hit a snag: According to his musicians, the Vegas casino establishment wanted ownership of the idea and were less interested in working with O’Day himself. “He needed those people if we were going to play in Las Vegas,” says Caywood. “He wanted all the glory. The shit hit the fan.” When the run ended in March 1979, Caywood recalls “a big blowup” over money, and the band broke up. O’Day fled to Florida — supposedly, Gamble heard, with $120,000 of their earnings. (“I wasn’t there, but he wouldn’t do that,” counters Effie. “I’m sure he didn’t have the money. I don’t know where it went or if somebody didn’t get paid.”)

Infuriated, Gamble says he followed O’Day back home to Florida to demand his money. He heard O’Day was now working with a country band — something about tributes to country singers — and tracked them down in a bar. O’Day wasn’t there, so Gamble had to content himself with walking off with a piece of stage gear.

In the aftermath of the collapse of Rock and Roll Heaven, Danny O’Day went in search of an encore. Returning to Ocala, he found his marriage falling apart and began working construction jobs. He and Effie were divorced in 1979. “We just sort of grew apart,” she says with a sigh. “He was having to be with the band, and the kids were in school. I wasn’t able to travel.”

But O’Day had one more tour to launch, and in a way, it was his eeriest one yet: He would become one of his own clones.

Ironically, the makeover would be inspired in part by Erin Rhyne, the female Elvis in Rock and Roll Heaven and the member of the troupe who’d been the most damaged by it. The atmosphere and show itself proved to be too much for Rhyne. As she later told the Orlando Sentinel, the whole show gave her “the creeps” due to “real weird girls who started hanging out during my shows, biker types.” She complained to O’Day about her female-Elvis role, but he wasn’t listening: “Nothing I said seemed to sink in,” Rhyne said. “I really hated him then.” On New Year’s Eve 1979, during the tour’s Reno run, she tossed down 50 sleeping pills and some champagne and hoped it would all end.

Rhyne survived, and overcome by guilt, O’Day brought her to Florida to help with her recovery. The two wound up singing covers in another band, poetically named Xerox, and before long, they became romantically involved. After the semi-highs of their casino days, they found themselves scrambling to survive, selling magazines to convenience stores and even hawking their own blood to pay the bills, as they told the Orlando Sentinel. The two still performed in what tiny clubs they could, but one day a waitress told O’Day, who was singing Kenny Rogers songs with another act, that he bore some resemblance to the “Gambler” growler. And with that, another lightbulb flicked on.

In February 1980, friends, family, and roller-disco ushers gathered at the Fifth National Banque, a club in Norfolk, Virginia, for what O’Day’s business manager would call “the first clonehead marriage.” Their faces covered in bandages, O’Day and Rhyne took their vows; even the bride and groom figurines on the cake were swathed in bandages. (When the ceremony was over, they had some difficulty eating the wedding cake.) The next night, they and a new batch of “clones” appeared onstage, and suddenly O’Day was Kenny Rogers and Rhyne was looking a bit like Linda Ronstadt, then at the peak of her pop career.

To become the “Gambler” balladeer, O’Day had a hair transplant, dyed his hair gray, and had his jowls tightened. O’Day later admitted the idea was also suggested by Rhyne and that he had his own doubts: “I said, ‘What, are you crazy? Me go in and have my face carved?’ But I was pretty ugly anyway.” And the hype factor, always important to O’Day, appealed to him, too: “Man, the monster maker himself onstage. Of course they’ll come.”

“Orlando Sentinel-Star”/TCA

“Orlando Sentinel-Star”/TCA

Rhyne sang credible Ronstadt covers, while her new husband dug into his performing past to mimic Rogers’ husky delivery. The gimmick baffled some who had known O’Day. “Danny — as Kenny Rogers?” Wise says. “Kenny had a really unique voice. When I heard that, it struck me as funny. We all went, ‘What the hell?’” But for Patten, who attended the service, it was O’Day’s new normal: “Again, it was Danny doing what Danny did.”

A month later, O’Day popped up at a Rogers press conference in Virginia, where he and a seemingly amused Rogers good-naturedly tugged at each other’s beards. O’Day rounded up another Jim Croce and another Elvis and found a local Florida musician to go under the knife to more closely resemble Buddy Holly. The group slogged on, hitting up clubs and nightclubs, until the next logical step in the traditional rock-band arc arrived — a reunion tour. Hazebrouck, who was still performing as Croce, rejoined O’Day and Rhyne for a Kenny, Linda, and Jim show. O’Day was finally the headlining star attraction he’d always longed to be, if not the way he’d quite planned it. (Actually, they didn’t go on the road so fast: The first gig, at a club in St. Petersburg, Florida, perhaps aptly named J.P. Bottom’s Lounge, never happened. Just as he arrived, O’Day was hauled off to jail for being behind on his child-support payments.)

Billed occasionally as “The World’s Greatest Clones,” O’Day, Rhyne, and sometimes Hazebrouck soldiered on for a few more years, playing clubs in their new home base of Virginia and nearby Pennsylvania. A husband hired them to perform at his wife’s 40th birthday party, since she was a Rogers fan. (“I knew it wasn’t the original,” the woman said of O’Day. “I asked him to show me his license and he refused.”) According to Rhyne’s sister-in-law, Wanda, Rhyne was happy, for a time: “Danny was the love of her life. Debbie loved all that. That was her life.”

By the mid-Eighties, O’Day was running out of schemes. His marriage to Rhyne fell apart. In 1985, he resurfaced in his home state of Maryland, managing a bar, Danny’s, on Route 50 in Easton. He only lasted there about a year, and soon after opened another spot, O’Day’s Pub.

But a drinking problem that had developed on the road soon overtook him. The pub — and everything in it, including Hamilton Beach mixers, towels, and soap dispensers — was sold in 1988. “He was always looking for his new project,” says Patten. “It was in his blood, and I want to think it was the drinking that prohibited him from doing more with his life.” O’Day went underground and died in 2003 at age 54 — according to Effie, of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. (Rhyne, by then remarried and known as Deborah Erin Bertalan, died of complications from a brain tumor in 2011.)

For Caywood, Gamble, and Wise, the scars have healed or are now barely detectable; Gamble’s mustache covers up his lip cut. Their memories of Rock and Roll Heaven are decidedly mixed. Caywood remembers O’Day as “a big ol’ shyster,” but the tour launched her into roles in productions of Evita and Jesus Christ Superstar, as well as an extended run at a Palm Springs club (singing both new and classic pop hits) until her recent retirement. “I bless you, Daniel O’Day,” she says, “for opening up such a large part of my life that came out of that.”

Wise still feels he and O’Day could have gone all the way with the act: “He had Disney World, all these people calling us — he had it in the palm of his hand and let it go,” he says. But thanks to that original operation, Wise still makes a respectable living re-creating Elvis in the Deja Vu Dance and Show Band, a multi-artist tribute act in Vegas. Gamble switched to Christian music and eventually became an ordained minister in Arizona, where he currently lives.

Whether he knew it or not, O’Day saw the future — our future. He envisioned a world in which celebrity worship would rule, everyday people could be elevated to stardom, and there would be no shame in any of it. “In 40 years, it’s become more acceptable to do something like that, compared to back then,” says Eyellusion’s Pezzuti. “From a standpoint of being original and doing something that wasn’t being done, I give him credit for putting his neck on the line.… He could have made a killing in Atlantic City.”

Some involved in Rock and Roll Heaven wanted to forget it ever existed. On their way out of Nevada after the tour ended, a few of the singers and band members made a pit stop in the desert. Dragging along the white suits they’d been forced to wear onstage, the musicians piled them atop one another and set the clothes afire, resulting in what Caywood recalls as an unholy muck of “cow patties, dirt, and melted polyester.”

A few years later, Caywood and her then-husband, who was in the band, returned to the site, and there the pile remained, in all its mangled glory. Caywood wound up taking the gross heap home with her, with the thought of encasing it in glass and turning it into a coffee table. The plan was scuttled when someone accidentally tossed out the whole mess. The mementos may be gone. But in the current landscape, where dead pop stars seem as prevalent as living, breathing ones, Danny O’Day’s outlandish vision remains open for business.

From Rolling Stone US