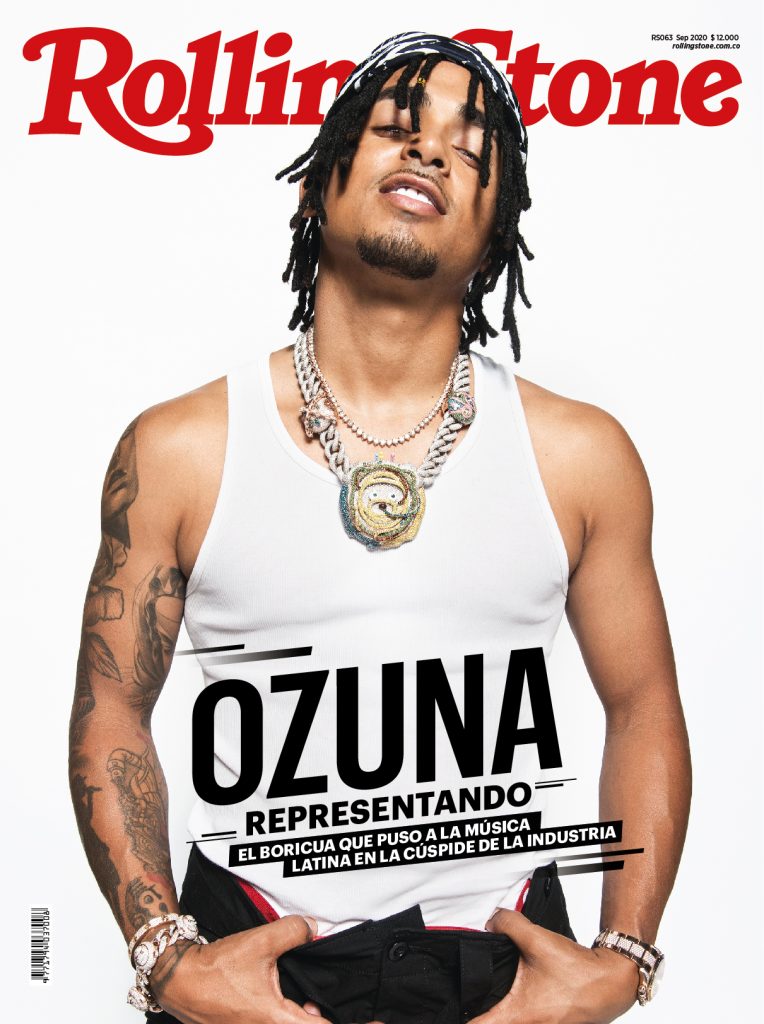

Gio Alma for Rolling Stone Colombia

He's sold more than 15 million albums, and he's one of the best-selling Latin artists of all time, and thanks to Ozuna, reggaeton is more popular than ever.

Seven months after the start of the deadliest pandemic of the century, on a summer morning, Ozuna is at his home in Miami. He wears a blue Lakers sweater, sneakers, long shorts, and a watch that looks more expensive than his mansion. He heads to an impromptu basketball game with several of his colleagues. Confinement is no longer an option in South Florida and unlike other cities in the United States and Latin America, the health emergency has been managed with certain freedoms and self-regulation. The Puerto Rican singer, who is finishing several things from his new album ENOC, wears a blue headscarf with which he holds his dreadlocks.

This story originally ran in Rolling Stone Colombia on September 7th, 2020. The interview has been translated from Spanish to English and edited for clarity.

It’s not easy for Ozuna. Considering the strong competition of today’s urban sound with hundreds of artists going towards the same place, it can be really demanding to be original in a genre where you think you’ve heard it all. After four albums, several dozen hits, four years at the top of Latin charts, and being the most-listened Latin artist on YouTube, Ozuna has developed an experimental work scheme that has led him to be the most important hitmaker of music in Spanish. “To maintain this you really have to be versatile. It’s not a matter of releasing everything I record immediately. Instead, I record a rap to be thoroughly focused so that the verses come out as they should be.”

The ever-evolving sound of Ozuna has paved the way for many of the artists who want to be heard in clubs. “Sometimes I record a lot of things that never come out. It’s practice, like a muscle. It’s pretty much the same thing,” he says. He discovered a direct formula to success that is based on the simplicity of his tracks, the romanticism of his lyrics, the power of his voice, and his melodic ability; unlike many other artists who found their tuning system in auto-tune. Ozuna’s name is included in several of the most successful songs in reggaeton history by collaborating – on multiple occasions – with some of the greatest exponents of the urban genre such as Daddy Yankee, Bad Bunny, Cardi B, and J. Balvin. Also, he has frequently worked with the largest producers in the industry.

In November 2019, I received a message from his manager. It was an invitation to attend the artist’s rehearsals for his presentation at the GRAMMYs, but I’m eight thousand miles away; eighteen hours by plane, three scales, and two continents away from America. I’m walking down the streets of Shanghai, China, with my travel companion, a renowned Spanish-speaking fashion editor. “I want perreo intenso tonight,” she says. A phrase that is probably only understood by those who were born in Latin America. She mentions it moments before entering a trendy alternative local club in the city. (Don’t picture those Miami or Las Vegas nightclubs with robots emerging from the roofs.) I don’t pay much attention to her comment, although I understand the sarcasm of it. Usually, almost all Latinos love reggaeton. So, I understand the nature of her desire.

The place is a rooftop with one of the best views in the world, amid several cultural disjunctions; on the one hand, there’s traditional communist conservative China, and on the other, one of the most modern and cosmopolitan cities in the world. When we started dancing, although we weren’t the only Latinos in the place, it was impossible not to draw attention. Latinos dancing salsa! It’s clear that in popular, non-professional terms, Latinos are the best dancers in the world. And it’s something that goes beyond music, genre, or academia. We grew up listening to salsa, bachata, champeta, merengue, and son. Everyone in our generation learned to dance for a basic human need: to flirt.

Minutes later, a Latin surge started. First, some salsa classics and then, hit after hit of reggaeton; “Quiero repetir,” “Mi gente,” “Escápate conmigo,” “Criminal,” “Despacito,” “Calma,” “Vaina loca.” For a moment I transported myself to several of the best Latin music venues in the world; La Descarga in Los Angeles, or Bazurto Social Club in Cartagena. I quickly understood the relevance of Latin music in the night scene and clubs around the world, something many of us have openly criticised. Particularly, the genre has had criticism in several Spanish-speaking countries, precisely because it’s “club music only.” As if enjoying dancing would fill us with insecurities that prevent us from giving it the importance that the genre has acquired in the last decade. Actually, I very much doubt that Tego Calderón felt ashamed in the nineties because his music was number one in nightclubs, or that Daddy Yankee worried about some radical commentary from the specialised critic when he got the whole world to dance with his biggest hit, “Gasolina.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

When you listen to music in Spanish while being so far away, in cultures so different from the Latin one, you feel nostalgia and imminent pride. “Quiero repetir” – a collaboration between Ozuna and J. Balvin – was playing at the height of the night in one of the most unexpected and remote clubs from Latin America. The “ecstasy of perreo intenso” kicked off. Minutes later, we had a group of strangers dancing around us. From that moment on, and for two more hours, all the music was in Spanish and mostly reggaeton. One thing that particularly draws my attention is that, in most of the greatest reggaeton hits that can be heard in clubs around the world, there is a voice that is constantly repeated: Ozuna. The reggaeton artist with the biggest digital figures of all time and the highest number of weeks in the official charts.

Photograph by Gio Alma. Styling by The Brand by Brandon Vega. Makeup by Pablo Rivera

In May, the artist is in Puerto Rico a few days before releasing his next single “Caramelo,” a song that talks about a forbidden relationship. As is the case with everyone, the 28-year-old artist Juan Carlos Ozuna Rosado – better known as Ozuna – is a victim of the insatiable crisis in the music industry caused by the pandemic. “This is very difficult, brother. And I guess it’s the same for everybody. I’m out of shows and you know I’m used to touring,” he tells me with his Puerto Rican accent on the other side of the phone. He’s secretly working on what will be his new album, a classic reggaeton album.

Ozuna was born in San Juan and grew up between two Caribbean cultures. His mother is Puerto Rican and his father – rapper Vico C’s backup dancer – who died when he was three, was Dominican. Thanks to his paternal grandmother, who assumed his upbringing, Ozuna grew away from the dangerous surroundings of Puerto Rico’s streets and gangs. His interests were placed in a healthy environment around school and work. “My grandmother always taught me to work and to understand that you have to work hard for yourself because no one else is going to do it for you. So I always focused on that. That was the environment I grew up in: work and family.”

Juan Carlos connected with music from a very young age and started in groups of boys who wanted to be like the Backstreet Boys: “They were all white and I was the only black kid in the choir. So I was the black one of the group.” Somehow this made him feel like he was in the wrong place. From that moment on he intended to undertake his own project and in one singing contest he was asked to perform “Color Esperanza” by Diego Torres. “At that moment, boom! I realised what the melodies were, the tones. I remember that at that moment I truly learned what singing was because I didn’t really know anything about it. That’s where I connected and started my entire development as an artist. That song was very important to me.”

He started in music from the age of eleven with the direct influence of artists such as Baby Rasta y Gringo, Daddy Yankee, Hector El Father, and Tito El Bambino. Those were the real beginnings of Wisin y Yandel and Don Omar. He grew up listening to all of the most traditional and greatest artists of the urban genre in Puerto Rico. “My grandparents gave me a walkman and I was crazy with my Baby Rasta y Gringo cassette. I remember when it was stolen from me, that was very frustrating because then I wanted to know what reggaeton was. Ever since I was born, everything in my life was reggaeton.”

All reggaeton artists in Puerto Rico, especially those who started their careers in the 1990s, have a very important connection to rap and what the “street” culture represents in artistic expression. Rap and reggaeton were integrated as a counterculture response in different scenarios of segregation and the Government’s negligence. “Sure, I grew up in that environment too, but that’s what I liked about Wisin y Yandel. Although they were also street, they started a path for romantic reggaeton.”

And this may be one of the most important turning points of the genre. Rap in Latin America, unlike the Anglo market, has been stigmatised and relegated to being an explicit street culture. Thus, in the late 1990s, reggaeton with rap and Caribbean roots was the genre that the music and recording industry found to popularise a Latin product that could work anywhere in the world. A product that was danced in nightclubs but could also attract younger audiences interested in new sounds. Like salsa in the 1970s in New York, the genre developed from the street to clubs and penetrated popular culture transgressing all language barriers.

Latin music has reached an important place in popular culture all around the world, and a very relevant position that competes with the greatest artists of urban music and rap in English. Reggaeton is the genre that has taken music in Spanish very far away. It has different nuances, from the alternative sound of songs like “Pa’ que retozen,” to great pop hits like “Caramelo,” and Ozuna represents the new generation of the genre. He adopted the romantic heritage of artists such as Yandel and Zion and created his own sound in the midst of one of the most competitive genres in the world. Partly due to many artists that didn’t make reggaeton and now have oriented their sound towards dance hall.

For years I was convinced that the success of the genre had a lot to do with a wave of Spanish-language music hits that came with each decade. But that night in Shanghai, I understood the true power of the genre and reggaeton artists who have made everyone dance genuinely, as other Latin artists did, but this time without it necessarily being a seasonal phenomenon.

The next day I answered a pending message and started a genuine search for the big names of reggaeton. Born in Puerto Rico and friend of the most important exponents of the genre, Residente told me that when he included a reggaeton beat in “Atrévete-te-te,” this was a breaking point in his career and the history of urban music. Dance hall as a harmonic and rhythmic base began its dominance in global music.

Photograph by Gio Alma

It’s the first week of February and Ozuna is ready to release his new video: “100 preguntas,” a beautiful song dedicated to Puerto Rico, where it shows the power of his voice and a different proposal in his catalog. “I’m not feeling well, baby, if it’s not with you.” The pandemic is just arriving in the Americas and his team continues to confirm the details of his U.S. tour. We talk on the phone again and I can tell he’s relaxed. Ozuna is a mature artist. A family man and an artist who understands the relevance of this interview. He takes his time to answer each question, has no contradictions, but looks for the precise words for each answer. His tone is warm and his voice is full of confidence in every comment. He is an artist who has no insecurities and is convinced, beyond labels and bling bling, that reggaeton is a global power. In Ozuna, the reggaeton genre found its perfect artistic representation that navigates between pop and classical rhythms such as dembow and dance hall. Last year, he set three Guinness Records for being the Latin artist who has been on the official charts of the music industry for the longest time and another one because in 2019 he was the most-watched artist on YouTube.

For many years reggaeton was stigmatised, rightly so, by its strong misogynistic content. But intentionally, in recent years, a sector of Latin American feminism turned it around and appropriated it in a particular way. Consciously departing from any gender discussion, since his beginnings, Ozuna was respectful of the female figure in his music and preferred to focus on lyrical and melodic romanticism. “I don’t agree with that thing of tarnishing or talking bad about women, you know? In fact, in the most successful songs I’ve ever had, women were the centre of my inspiration,” he says.

The Puerto Rican, who faced the pandemic like many other artists from a creative angle, faced his fears to develop songs that are on another creative level and a step beyond his own records. “I learned along the way and I’m at my best creative moment. We’ve learned, we’ve experienced. I’m already going straight to what I really want to do,” he says. “This album was easier for me because it was a matter of applying everything I’ve learned. It was identifying the mistakes made on previous albums, and not falling back on the same thing.” The free time left by the pandemic on Ozuna’s schedule gave him the chance to sit down and think about what he really wanted to do. “When I called Doja Cat and Sia it was really fast. Also with Daddy Yankee, everything took no more than 24 hours.” The album was recorded at La Base, Wisin’s Studio in Cayey. “I feel it was a very organic thing, something God wanted to happen like this.”

ENOC is an album that rescues the classic style of reggaeton, with piano melodies, guitar arrangements and also, multiple collaborations that also transcend the language barrier, as is the case in “Del mar”. A beach song featuring Sia and Doja Cat. Ozuna, without skimping, presents a master album that navigates throughout Caribbean rhythms: dembow, dance hall, soca, reggaeton, trap, and hip hop.

“Enemigos ocultos” is a gangsta rap of almost eight minutes featuring Arcángel and Wisin, among others, which immediately evokes one of Wu-Tang Clan or La Coka Nostra classic songs. It’s a statement of principles of what Puerto Rican artists are in the genre. There’s no place for artists who don’t live up to the verse. “I’ve defeated them in all rounds! You’re not rude, all you are is a boy scout!” Wisin says in one of the most squabbling interventions of recent years in reggaeton. “I bought a plane because I wanted to fly,” Ozuna says, unloading all ammunition from a machine gun in Puerto Rican verse.

“No se da cuenta” is a dembow in which Daddy Yankee leads a melodic chorus. A hit ready for the clubs. “Un Get” is a slow soca atmosphere, another song for the Caribbean summer. “El reggaetón” is a classic theme reminiscent of the 1990s scene, with a dry snare drum and unaltered bass drum. “El oso del dinero” is an American trap. “They all came together to stop me,” Ozuna says, showing his most rapper side on the album. He doesn’t lack words in a concise, belligerent verse. In “Duele querer” the singer goes back to the piano and the romantic ballad.

“He gave melody to trap in Spanish since he started with “La ocasión.” He gave it a unique colour. His tone of voice and romantic themes resonated with the audience and made a difference. Besides, he is a great live performer, who transmits and proves that he enjoys what he does. He knows what he’s doing,” J. Balvin says in a WhatsApp message when I ask him about the contribution of the Puerto Rican to the genre.

Ozuna has the big responsibility of keeping Spanish and reggaeton music at the top of the charts. At such a young age, he’s by far the present and the future of urban music. He has collaborated with the most important exponents of the entire industry, and his future could be the bridge to a generation of new artists who move millions of followers but still haven’t found a sound. He’s a specialist in one thing: to sound authentic and refreshing in a sea of salt water.

Photograph by Gio Alma. Styling by The Brand by Brandon Vega. Makeup by Pablo Rivera

Since the moment you started writing songs, were you fully clear about what you wanted to do with your music career?

I don’t know if it was so clear. It’s hard to have clarity when you’re so young. But what I can say is that things come when you least expect them. I didn’t set out to try to be a musician at all costs. Initially, I took it as a hobby that you can never stop doing, but although I loved music I also had a job, I had to get down to work, I have children and a family. I’ve written songs, poems since I was a child. But when I was truly interested in music or being an artist or creating something within the industry, I had to work and make ends meet at the same time. You can’t live on the dream alone. One has to do something and work.

When I left to work, I’d go straight to my studio to work on my music. But I can’t say for sure I was waiting for all this. I never had those kind of thoughts: “I want to be the greatest.” I’d be lying if I told you that because it was a process with a lot of work and frustrations in between. It’s everything you learn along the way, every step you take, applying what you’ve learned in what you love about music and the music business. So it was little by little. It’s not how people think it is, that it’s all from one moment to the next. Of course, who doesn’t dream of being a great artist? But it wasn’t just that, and if it was, I’d be lying to you.

What do you think was the defining moment and the trigger for reggaeton’s globalisation?

Oh God, you’re gonna get me in trouble! For me, it became global when we came out, those of the new generation; Bad Bunny, Anuel, J. Balvin, and me. Sure, Daddy Yankee planted the foundations and he set the mood, but it was when our new generations came out that we spread it all over the world. Before 2010 we traveled to Latin America and elsewhere, but it was not what it is today. Today we go to Europe and do massive festivals and shows. Before, for you to be able to do a massive show, it was very difficult. If anybody, Romeo. But reggaeton didn’t. Daddy Yankee did concerts, of course, but they weren’t as massive as they are now. For example, at a reggaeton concert today in Argentina or Italy, there are 50.000 people. Before, if you held a Yankee show with Wisin y Yandel, I doubt that it was that big.

“Despacito” was a song that brought this to everyone, although done before by Yankee with “Gasolina.” Sure, nowadays music gets faster everywhere. Now I release a song today and boom! Either in Egypt or Israel, they are already listening to it. I don’t think it’s the same, nor can it be compared, but I’m sure reggaeton was globalised now. And it should also be noted that there were many slammed doors on Daddy Yankee, Wisin y Yandel or Don Omar, that started to open, bam, bam! It took a lot of work for them.

Sure, and that might be my point. Do you think these new generations have been able to reap the fruits of all the efforts of a generation of reggaeton artists who have been making their way in the industry since the 90s or 2000s until you arrived? Do you consider that these new generations have enjoyed this market opening or those doors that they left open?

Sure, we’re reaping the fruits. We’re going this way with doors open. They had them closed, they had to fight. In Puerto Rico, they wanted to ban reggaeton when it came out. They wanted to put up a warning to ban it everywhere. But little by little it became popular and to this day it continues to grow. I don’t think it’s the top, because we’re still going up. The genre is at its best. There are many artists with new projects, something not seen before. There used to be only five artists and now there are thousands still in development. Every day you hear a new thing. Sure, some leaders chart the way, but new proposals are going to continue to grow.

We can say that reggaeton was one of the pioneers in terms of collaborations between artists because they did it from the beginning. One can listen to a very classic song of the genre where there were already five artists singing in a single track. What do you think about this work process that remains very important in reggaeton? How do you handle it and how do you choose the artists you want to collaborate with?

To choose my collaborations I focus on the other artist’s talent. I see their growth. There are many of these new artists that I like and in collaborations, not everything is for business. Some things just don’t work, and that maybe they wouldn’t be successful today, nor tomorrow, but you do it for collaborating. Therefore, for me choosing is a very complex task, because I like several artists that maybe no one knows, so it’s not an easy decision to make. But we also recorded a song together and everyone started to know who they are, and that’s very rewarding. I believe in good music, I don’t believe so much in the name, or who the artist is. Moreover, when you get a good song that you can collaborate on, it’s something you can’t let go of, whoever might be. You have to do it.

Photograph by Gio Alma. Styling by The Brand by Brandon Vega. Makeup by Pablo Rivera

There is another very relevant figure in reggaeton, and it is that of the producers. How do you choose a producer and how are you sure it’s the sound you’re looking for at some point?

Usually, I always work with the same producers, unless it’s a song for the Anglo market. Anyway, my producers are mostly American; DJ Snake, Tainy, Chris Jeday, Gaby Music. I almost always work with them. I think the reggaeton industry is a very closed circle in terms of that aspect. And of course, there are always several new producers, but in my position I always want to record with the very best. With whom I know I’m gonna be pleased with the result. Likewise, when a good new producer arrives with good ideas, a good job, and a good proposal, you have to take it into account as well.

That leads me to think that you’re in a competitive environment where new songs and artists are constantly being released. How is your strategy to be innovative in a genre that has more and more offer in the market?

That’s a very difficult thing to explain because it’s a talent that we’ve acquired with work. But it’s not something I can explain to you that easy. I go to the studio with a good instrumental [track], and I already have a theme and rhythm of how to work a song. And that only happens with time and experience. Night after night inventing, trying to do this and that. I call it my turbine, I’ll turn it on and that’s it. We know where we’re going. And the people who work with me know that I work like this. It’s already the same technique I’ve developed and as I’m telling you, it’s getting stronger over the years. Of course, I slowly learned and it’s not something that happens overnight. Maybe new talents believe that they’ll become an artist in a day. And that’s not true. This is a super long process because I keep learning more and more each day.

How do you feel about the fact that reggaeton has governed music in Spanish – especially pop- for a while now?

Good, because that shows that we urban music artists are leaders of a sound and that we make something that people of other genres like or would like to do. Look, now even Reik, whom I like, are doing good in reggaeton and they used to make another genre. I even think they sing better than many reggaeton artists, it suits them. That’s what I mean when I say that many artists from all over the world want to make music, not specifically reggaeton, but urban music. Many rhythms aren’t reggaeton, but they are things within us that are urban.

Do you consider Puerto Rico’s urban music different from that of the rest of Latin America?

Of course, it’s extremely different. I don’t know anything about that controversy, where was it born, or where the genre comes from, but the parents of all this are in Puerto Rico. For me, reggaeton is from Puerto Rico. If you look at the way we talk, is almost like singing a reggaeton song. That’s the best answer I can give you. Tell me where the three greatest reggaeton artists are from… And that’s not belittling the work of others, but in Puerto Rico, there’s a lot of musical fever for the genre. That spread to all around the world, and there are artists everywhere. But for example, if you listen to “Gistro Amarillo,” it’s a song that can’t be made by an artist other than Puerto Rican because of the wording, the jargon, and the whole theme. It’s purely our culture.

Partly, I consider that there’s something that differentiates Puerto Rico’s artists. Usually, the urban artist from there has a lyrical, vocal, and rapping ability, which you hardly find in other reggaeton artists in Latin America…

That’s our ability: Versatility.

Today, with such competition in the market, where do you think the success of a song lies in?

Well, speaking specifically of reggaeton, there are many success factors. The music and instrumentation, the lyrics, the artist who sings it, and how he projects the song. How you market it. Some songs are an instant hit, but others need a lot of work to reach the public’s ear. When I started, there was only one way to do it and it was with the quality of your music because digital platforms like Spotify and AppleMusic were just starting and they were all starting hand in hand with the music we were making. Artists such as El Conejo [Bad Bunny] and myself. Nowadays everything is very different, there are multiple ways and strategies to do marketing.

You grew up in that natural environment of urban music. At some point, you considered that, somehow, the genre had a misogynistic character?

Well, no, because my music doesn’t have any of it. And don’t take into account certain things I’ve said in some songs because it was more leaned towards wordplay aimed at adults. I consider that today there is no room to offend women in music in general. It’s a different time. Maybe I see it in other songs that aren’t mine, but I’m really careful about that. I mind my own business. I’m me. I know the urban genre is huge and there’s a lot to take in, but I’m taking care of my part. I don’t offend women, I don’t disrespect them in any way in the lyrics. There are some playful, spicy things that we all like, but in a matter of tarnishing women, that’s not allowed on my record label. We don’t do those kinds of songs.

In a couple of your interviews, I’ve heard that you like to be played in clubs, and that’s a very honest thing, considering that a lot of artists in Latin America run away from the concept of just being a club artist. How do you see the relevance of your music on clubs?

I have songs for any kind of situation, romantic ones or for the club. It also depends on the feeling you give it.

Sure, and that’s how I feel about songs like “Temporal,” “Amor Genuino,” or “100 Preguntas.” How does your creativity work when it comes to doing such different things?

I always think of all kinds of people, all kinds of situations. That’s why, thank God, we’ve done well with all the records we’ve made until now. We always seek to be versatile; if you don’t go to the club, you have this option, but if you go, you have another one. It’s a very important thing for me, I don’t like saying the same thing in the verses or the choruses, I do have the same theme, but always with different tones. Try to make it sound different. Make different music.

Taking into account the globality of the genre and also taking advantage of its popularity, what’s your strategy to reach other audiences with your music?

Clean lyrics that reach all hearts. Situations. Simplicity is what people like these days. Sometimes we complicate ourselves by looking for things and exaggerating. It must sound differently. I don’t know what my melodies have, I can’t tell you “this is the trick,” but kids, women, and older people like it. And I think that’s the result of how we do things, from the heart. The team we have is, as we say in Puerto Rico, a beast. The strategy is the same, working as a team and adding a lot of heart. Not do things to upstage others, or for money. We work hard to increase our income, but we do it from our heart to the public. I feel like that’s the most important thing.

Why do you think reggaeton is perhaps having a greater impact in the United States than in Latin America?

The thing is, Latinos are already everywhere in the world. There haven’t been as many Latinos in the United States before as there are now. Besides, by mixing Latinos with Americans, and showing and teaching our music to them, and in turn their music to us, everything has been mixed. That didn’t happen before. Current phones, technology, iPads, all those things have made the process much easier for music to reach everyone. Besides, Latin music has a lot to do with dancing, and our reggaeton is danced by being very close to the other person. It’s something sensual that is sought, something that it’s liked all over the world, and I think it will be like that for a long time. Maybe that’s why they’re liking it so much in the United States because it’s something new to them. We were used to it.

In these current circumstances, have you been able to analyse the positive and the difficulties of being away from home and on tour all the time?

They are mixed feelings. On the one hand, it’s difficult, but at the same time, it’s somewhat pleasing because it means that things are going well. It’s hard for family, children and that moment when you have to stop being with them, but at the same time, it feels good because when we go out, we’re on the other side of the world giving a concert or singing at awards and things like that. And so far they’re happy too, they know I’m working. That’s why it’s a 50/50, I’m not telling you I don’t get sad, I keep calling them all the time to keep an eye on them.

What do you think about this recent controversy of wanting to remove the urban music label from reggaeton?

You can put any label on it and it’s always going to be the same. I don’t have a problem. I don’t know what to tell you about that because, those of “urban” music, we have always been artists and our music is as pop as any other. I prefer that our music is always called reggaeton, because there is something within the concept of urban music that I don’t like, and that is that urban is anything. But reggaeton can’t be done by anyone, not like we do it. Even if they name it whatever, we’re gonna keep succeeding.

How do you handle the pressure that every song should be a huge hit in the environment you’re in?

I don’t feel that pressure, we’ve already made over 120 hits in general. More than 110 multi-Platinum songs, more than 110 songs at the top of the radio chartings. Nowadays, I think it’s done for love and desire. Sure, I still have that desire of being big, but if I insist on thinking that every song must be a success, I’m going to fail with everything that I release. I focus on making good music, getting together with good composers, with people who always add up and bring good ideas. As many people might think, I don’t do everything on my own, we have a team. It’s musical fever, you have to be part of a movement. Every day you have to be able to make something new, and I think we all have the same hunger that we had when we started and wanted to grow in this industry.

Photograph by Gio Alma. Styling by The Brand by Brandon Vega. Makeup by Pablo Rivera

How do you measure your success? What makes you feel happy and successful?

The story I’m writing on this Earth. Four Guinness Records. 11 Billboards. More than 20 nominations. You interviewing me for Rolling Stone. All those things please me, but what I can be most pleased and grateful for is seeing a happy audience singing my songs. That’s what makes you feel the best. When I’m on stage, I go all over the place, and that’s what I like most about concerts, that connection with the audience. Feeling the audience singing these new songs in Spanish, with so much passion, with heart, with love. That’s what keeps you going. It’s that love that the audience shows your songs and to you. That’s the real success.

What do you think is the essence of classic reggaeton that is now connecting with the audience? A few years ago the sound was different, and now the classics are gaining strength…

Maybe it’s the track… The drums… There’s something in the sound and production of that time. It’s a very strange thing; it’s very difficult to explain. Maybe it’s the simplicity.

What are your top three songs in reggaeton history?

“Gasolina,” Daddy Yankee, “Dale Don Dale,” Don Omar, and “Mayor que yo,” Luny Tunes.

I know that you’ve had the opportunity to work with Colombian artists. What do you identify in this new generation of Colombian artists like J. Balvin and Maluma? What contribution do you think they’re making to the genre?

The genre has been expanding; I mean that nowadays it’s easier for that to happen. They’ve been in the industry for a while and were also influenced by guys like Daddy Yankee, Wisin y Yandel, Don Omar. They work exceedingly well. I think Balvin is a guy who has a huge influence over what the trends are, and we contribute with music, rhythms influence, and many Puerto Rico producers. I think it’s a two-way relationship, something we’ve been sharing over time. I feel that the union we have made depends not only on Colombia but on other countries and other parts of the world that have collaborated with Puerto Rico’s producers and everything has always worked well because it’s done from the heart. That’s why I think J. Balvin and Maluma have also grown quite a bit, they have contributed a lot to this genre, they have also helped to mix it with fashion.

Considering the difficult situation that the music industry is going through due to a lack of concerts, how are you preparing for that? When do you plan on returning to the stage? And if that’s delayed, what’s your plan to remain relevant to the fans?

Music speaks for itself. There’s going to be a way to connect, I don’t know what it is, but a professional way of doing these shows will come. I think this is going to take a while. Going back to normal doesn’t look like it’s gonna happen next month, but we’re ready. I know God is working for that and we’re going to be able to hang out with our fans again and do what we did before. To be able to embrace us, to be able to greet us as the world normally did. The time will come. I’m in no hurry. I don’t worry about it because my thing is to keep making music and take that to different parts of the world. I think that’s the main thing. Doing shows is in the background, for now, that’ll come later. Right now we’re creating and continuing to grow as artists. As soon as the shows open, trust me, the audience will be eager to see us more than ever.