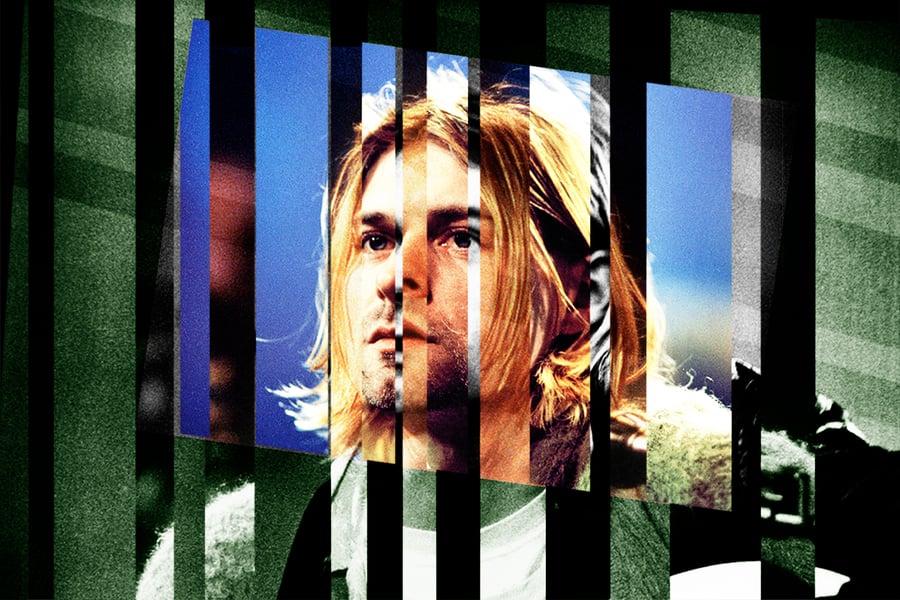

Ever since Kurt Cobain’s death in 1994, Nirvana fans have hypothesized about the music he would have made had he lived. But other than “You Know You’re Right,” the scabrous, throat-shredding meditation on confusion that Nirvana recorded a few months before his suicide, and a few comments he told confidants about potentially collaborating with R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe or going completely solo, he mainly left behind question marks.

Now an organization has created a “new” Nirvana song using artificial-intelligence software to approximate the singer-guitarist’s songwriting. The guitar riffs vary from quiet, “Come as You Are”–style plucking to raging, Bleach fury à la “Scoff.” And lyrics like, “The sun shines on you but I don’t know how,” and a surprisingly anthemic chorus, “I don’t care/I feel as one, drowned in the sun,” bear evocative, Cobain-esque qualities.

But other than the vocals — the work of Nirvana tribute band frontman Eric Hogan — the song’s creators say nearly everything on the song, from the turns of phrase to the reckless guitar performance, is the work of computers. Their intention is to draw attention to the tragedy of Cobain’s death by suicide and how living musicians can get help with depression.

The tune, titled “Drowned in the Sun,” is part of Lost Tapes of the 27 Club, a project featuring songs written and mostly performed by machines in the styles of other musicians who died at 27: Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, and Amy Winehouse. Each track is the result of AI programs analyzing up to 30 songs by each artist and granularly studying the tracks’ vocal melodies, chord changes, guitar riffs and solos, drum patterns, and lyrics to guess what their “new” compositions would sound like. The project is the work of Over the Bridge, a Toronto organization that helps members of the music industry struggling with mental illness.

“Drowned in the Sun” (In the style of Nirvana)