Late-night confessions and studio revelations with the fast-rising rapper – who wants to be the greatest of his generation

“Who are these fucking bozos on our turf?”

Jack Harlow is in the back of a big black SUV next to his childhood best friend, Urban Wyatt, mock-glaring through his Prada sunglasses at a couple of little kids on a swing set in a Louisville, Kentucky, park. Everyone in the car cracks up, but to be fair, this whole low-to-the-ground city pretty much is Harlow’s turf these days. In December, it was Jack Harlow Day in Louisville, by mayoral proclamation, during a run of hometown concerts.

One of those shows raised money to restore a gazebo-like structure right here in Cherokee Park, the site of some fond memories. “Smoked a lot of weed in that thing right there,” says Harlow, stepping out of the car on an early-February afternoon, his white John Geiger low-tops crunching in fresh snow. “We loitered here in this park. When you didn’t have nothin’ to do, but you had cars, you’d come here.” Harlow, taller and more broad-shouldered than he looks on, say, TikTok, is wearing light jeans and a thin black sweatshirt, no jacket, despite the icy air from the Ohio River. He slides his manicured hands into his pockets.

“I was fucking in this park,” Wyatt says, with a touch of wistfulness. “I was fuckin’ like a deer.” The longhaired Wyatt, also Harlow’s videographer, dresses at all times like he’s ready for a Harmony Korine casting call, but he’s a sweet, unassuming, oft-THC-enhanced presence.

Harlow nods. “I was fuckin’ against a tree over on the side of the river over there,” he says, pointing out the spot. “And definitely over here.” He talks almost exactly how he raps, in a sleepy, melodic Southern drawl.

The loitering and weed smoking and fresh-air fornication wasn’t all that long ago; Harlow is just 24 years old, with his teenage texts still in his phone. Back in the car, he half-jokingly ponders a visit to a high school girlfriend’s house, digging up a lengthy exchange of messages with her mom, who sounds chill. (“Thank you for your sweet note,” she wrote. “I appreciate you understanding. We do want her to take time to concentrate on school for end-of-year exams.”)

Harlow was already achieving some local fame back then, and now he’s a budding superstar, a vanishingly rare white rapper with credibility, co-signed by two of his biggest heroes, Drake and Kanye West. “This n—a can raaaaaaap bro,” West wrote, memorably, on his Instagram, before recruiting Harlow for a guest spot on Donda 2. “And I’m saying n—a as a compliment, Top 5 out right now..”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Last night, Harlow was up late memorizing lines for a self-taped audition for an acting role that turns out to be a remake of White Men Can’t Jump. (“They think I’d be a perfect fit for it,” he says.) He ends up getting the part, the one Woody Harrelson originally played. “There’s just something surreal about where I’m at in life,” Harlow says. “It’s just crazy to think that you were walking the sidewalks dreaming, and then to be living it — it’s like a movie, bro. You’re one of the lucky people that got to live a movie-esque life. And I’m in the middle of the fucking movie right now.”

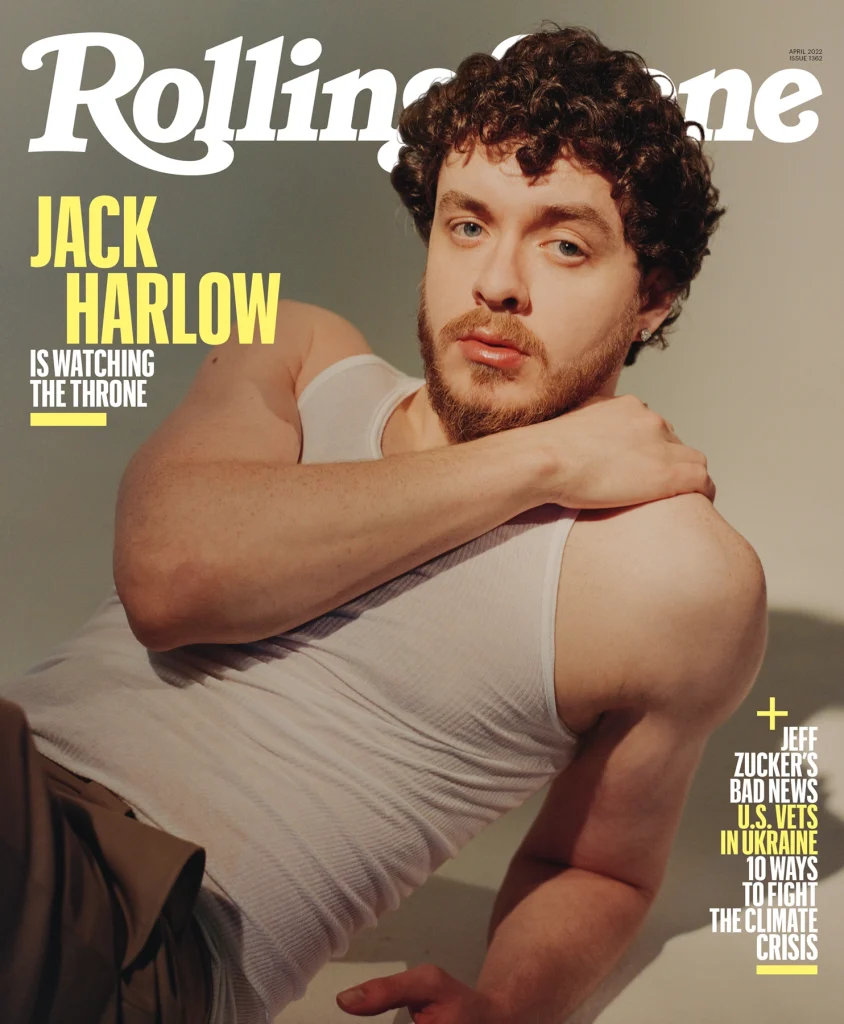

Jack Harlow, photographed in Los Angeles on January 31st, 2022 by Ryan Pfluger. (Photograph by Ryan Pfluger for Rolling Stone. Director of Creative Content: Catriona Ni Aolain. Fashion direction by Alex Badia. Produced by Brittany Brooks. Grooming by Tess Anntoinette. Styling by Metta Conchetta. Tank by Tommy Hilfiger. Pants by Louis Vuitton.)

In the car, Harlow blasts “Nail Tech,” the propulsive, braggadocious first single from his upcoming new album, Come Home the Kids Miss You, due May 6. The single only hints at what’s in store on the album, which is Harlow’s most distinctive to date, thanks in part to a bespoke, detail-intensive, Ye-inspired production process.

“It’s probably my least favorite song on the album,” says Harlow, who tends to prefer his more vibe-y and lyrically substantive tracks. He’s already deeply sick of a fan-favorite anthem from his last album, “Face of My City,” though he’s still proud of the hit “What’s Poppin.” “But I know the effect it’s gonna have on people. I’m spitting, and there’s energy behind the beat. . . . I have different tastes. I can’t believe people love to listen to ‘Tyler Herro’ on repeat and ‘What’s Poppin’ on repeat.”

Harlow sounds, at times, like he’s emerged from a very low-powered time machine. He references rappers in their 30s and 40s way more than his actual peers, as if he’s gunning to conquer the rap world of 2010 or so. His focus on lyrical prowess, meanwhile, feels like a throwback to an even earlier era. He wants to make a direct claim to the hip-hop throne, which would arguably make him the first white rapper to do so since Eminem; the late Mac Miller was great, but wasn’t into proclaiming it.

“That’s what made Em so hard — he was in the dog pile,” says Harlow. “I want to be the face of my shit, like the face of my generation, for these next 10 years. We need more people in my generation that are trying to be the best, and you can’t do that with just ear candy, vibe records. You got to come out swinging sometimes. . . . My new shit is much more serious. Right now, my message is letting muh’fuckers know I love hip-hop, and I’m one of the best in my generation. You can’t do that with nonchalant, like, ‘Eeey, I got the bitches,’ in clever ways over and over again. I got to dig deeper this time.”

Drake showed up at a Harlow concert in Toronto last year, and invited Harlow back to his house afterward. Harlow had just one thing he needed to ask him, though he’s keeping whatever answers he got to himself. “Towards the end of our time, I just wanted to keep it real,” says Harlow. “Like, you’re familiar with what I do, you came to my show. Like, you’re up to speed. He knows what’s going on. So: How can I be better?”

Hang out with Jack Harlow long enough, especially in Louisville, and you’ll end up feeling like you’re inside a Jack Harlow song. We keep driving down streets — Baxter Avenue, River Road — that he’s rapped about or used as song titles. And then there’s the 21c Museum Hotel, a funky downtown spot where he likes to stay when he’s in town. (He’s just bought his own place, however, and plans to relocate back to Louisville for good after a couple of years as a nominal resident of Atlanta. “I really want to give back to this place,” he says. “I really want to change the city. Give out opportunities, fix some of the poverty as much as I can.”) The hotel inspired his seduction tale “21C/Delta,” and today he’s staying in its penthouse, a full-floor suite that comes with a private staircase and a giant arty photograph of a shirtless Justin Bieber alongside various nudes in the hallway.

As Harlow himself points out later, the current scene in the penthouse is also highly reminiscent of yet another of his songs, “Already Best Friends,” especially the last verse, where he deftly sketches a flirtatious conversation with two young women. Right now, two twentysomething women are, in fact, hanging with Harlow in the penthouse’s living room. One, Tahira, a waitress at a strip club who describes herself with a laugh as “a 26-year-old legend,” once appeared in a video by local hero Bryson Tiller, and she pops up in several of Harlow’s videos as well. The other, Ciera, is a manager at a car-rental chain, with a collection of tattoos she conceals from her co-workers, including a brand-new one on her thigh from earlier today. “I’m really on my girlboss stuff,” says Ciera.

Harlow himself has zero tattoos. “I’m an evolutionary person,” he says. “So doing something permanently intimidates me. And I like the thought of being an actor and having no limitations in that.”

Photograph by Ryan Pfluger for Rolling Stone. Shirt by Tommy Hilfiger. Jeans by Levi’s

Mostly, Harlow hangs back and encourages his friends to talk. “That’s just such an ill thing,” he says later, “to be outnumbered by women in a social situation, and they’re dominating the conversation,” he says. “Great shit comes out of that.”

Then again, a lot of the conversation ends up being about Harlow himself, and he doesn’t mind. To everyone’s vast amusement, Ciera reveals Harlow played “a major role” in helping her redefine her sexuality. (“That’s gonna be the cover line — ‘Jack low-key changed my sexuality,’ ” Harlow says.) They first met when Harlow “shot his shot at her” right on the street during a drunken night at the Louisville bars a few years back, when she identified as a lesbian. “He’s so cute,” Ciera told Tahira at the time. “He looks like the girls that I date!” Now she dates men exclusively. “ ‘I completely retired from being a lesbian,” she says. (For the record, she emphasizes that Harlow can’t take all the credit.)

They all reminisce about a night out that “almost” ended with skinny-dipping at a hotel, and Harlow sighs. “Those were the days,” he says. “I used to get so twisted back then. I used to get shitty. It was all so new to me.”

“It’s fun,” says Ciera, “to see the evolution of Jack.”

“I had my glasses,” Harlow says. “I still had the ring curls. I hadn’t figured out how to dress or look yet. I just was very, like, raw.”

Since then, Harlow — who “didn’t even wash my face” for most of his life — has had a much-remarked-upon glow-up. “I’m just a late bloomer/I didn’t peak in high school/I’m still out here getting cuter,” he rapped in his highest-profile moment so far, last year’s guest verse on Lil Nas X’s hit “Industry Baby.” (Harlow, by the way, had been hesitant to accept guest-rapper slots on pop songs — “You won’t believe what I’ve turned down, because this pocket we’ve got right now is fragile, man. I’ve turned down so much shit that would have been a big ol’ bag” — but he’s enough of a Lil Nas X fan that he signed on without hesitation, only to find out that Nas’ handlers wanted to cut Harlow’s verse in half in order to shorten the song “for the algorithm.” He had to take his case directly to Nas himself. “I don’t want to be the eight-bar novelty hip-hop feature on this,” Harlow recalls telling him. “Fuck the algorithm.”)

Harlow quit drinking last year. He doesn’t think he had anything close to an alcohol problem, but he did end up drinking six nights in a row on tour. “I’m sick of waking up with a dry throat, sick of feeling bloated, I’m sick of the decisions I make on it,” he says. “I’m in my well-oiled-machine era. Because I can see my future right in front of me. And I feel there’s so many people counting on me outside of myself. I just feel like I’m a man. I don’t feel like I need to do boyish things anymore.”

He’s on a journey toward self-perfection, lifting weights each morning with his trainer, EJ Webb, a serene dude who travels with him everywhere. Harlow has optimized his food consumption, too, keeping it in check by simply consuming whatever’s put in front of him by his day-to-day manager, Neelam Thadhani. “I gorge things,” he says. “If I like a girl, for the first three weeks of knowing each other, I’m on top of her. I like food. I eat past being full.”

His beard is devilishly perfect; each of his earlobes is studded with a chunky diamond. He’s sorted out his hair situation, though he’ll always be scared of going bald like his dad. And even before the world’s seen his new muscles, he’s become a leading Gen-Z sex symbol, a development he’s almost tired of hearing about. “It started with ‘Who the fuck is this white boy? He’s dope.’ Then it arced into ‘Who the fuck is this white boy? He’s funny as fuck.’ ” The latter assessment started with a viral Genius video in which he coined the slang “bricked up,” a now-ubiquitous description of male arousal adapted from the Louisville slang “on brick.” “Now it’s the girl thing. It went dope, funny, girls. I’m ready to get back to dope.”

On the other hand, he loves having a fan base dominated by women and can’t imagine why any artist wouldn’t feel the same. “It’s sick,” he says. “I fuck with it! . . . To be able to make a song that women like is what it’s all about for me. There’s a lot of things it’s all about, but that’s a huge one. That’s really what you want, to make something that your crush wants to hear.”

There will always be at least one aspect of life distracting him from his relentless artistic and career ambitions. “I am poetic,” he says, “but I want some ass. You know what I’m saying?” He laughs. “I literally said that to a girl once. I was apologizing for my desires lightheartedly, like, ‘I’m a mammal. I’ve still got control over myself, but just the way a plant outside wants the sun, I have been engineered to want to reproduce.’ ”

Photograph by Ryan Pfluger

Harlow got an early start on both of his lifelong interests. When he was a kid growing up in rural Shelbyville, about 30 miles east of Louisville, on a patch of land with two horses, Buster and Mojo, he asked his parents for Barbie dolls. “Their first thought is, like, ‘Is he gay?’ ” says Harlow, whose family moved to Louisville when he was in third grade. “Then I started undressing Barbies. ‘He’s not gay.’ ”

It took slightly longer for Harlow to latch onto rap. His mom played Public Enemy and A Tribe Called Quest around the house; his dad, who sang at their wedding, is more of a classic-rock and country guy. But in Jack’s elementary-school days, he and his little brother, Clay, were more interested in superheroes, Star Wars, and Harry Potter. “I would wake up in the morning and dress up as Anakin,” says Clay, who’s two and a half years younger, “and he would be Obi-Wan or whatever.”

When Harlow saw Eminem in 8 Mile, he found a new hero to emulate. “That’s how it normally goes,” Clay says, “Obi-Wan Kenobi to B. Rabbit.”

By age 11 or so, Harlow declared he wanted to be a rapper, and never once wavered from that path from that day forward. “He and my mom would freestyle in the car,” Clay says. “They would put on instrumentals, and we’d be driving somewhere, and they would both rap.” It’s unclear if mom has bars: “I can’t remember any of her classic lines.”

Harlow dropped his debut mixtape, Extra Credit, under the name Mr. Harlow, when he was in seventh grade, before his “balls dropped.” Most of it, to his chagrin, can still be found online, and it’s a fascinating artifact, showcasing a very suburban-sounding, hilariously high-pitched kid who’s already achieved a fair amount of technical proficiency. The “hit” on the mixtape, among his peers, was a goofy ode to an air freshener, “The Febreze Song”: “F-E-B to the R to E to the Z to the E, that spells Febreze.”

By the time Harlow was a freshman in high school, he was getting serious interest from labels and managers who saw him as a potential child-star rapper; he even had a meeting at Scooter Braun’s house. He got close, but it all fizzled out. So Harlow went back home and “just went to work on a local level,” he says. “Burning CDs. Passing out mixtapes at school.”

At the time, Harlow was devastated that none of the deals worked out, but he’s grateful now. “I dodged a bullet,” he says. “I got to go to public school. I got to go to parties. I got to lose my virginity in a normal way. A lot of dominoes had to fall the right way for me to be good at being a rapper. Because I’m still a white guy and I didn’t grow up poor. I had to get perspective to say things that could be universally relatable. I got to finish high school. I got to be regular. I got to be humbled. I got to dress poorly. I got to figure myself out.”

His self-awareness rarely slipped. Harlow, whose parents run a successful sign business, cut a “Started From the Bottom” remix called “Started From the Middle” as a teen: “Middle-class neighborhood, yeah that’s where I started/And my neighbors ridin’ round shoppin’ at the farmer’s market,” he rapped, bragging of a “flow nastier than cafeteria food.”

For a long time, he was so determined not to front, to avoid pretending to be any harder or more street than he was, that he ended up leaning too hard on a nerdy image. “I was a cool-ass kid in school the whole time,” he says, even while he was recording lines like “Hands down my pants while I fantasize about Amanda Bynes.” “It took me a while to take my glasses off. I felt literally tethered to them, because I felt like, ‘You’re the rapper with glasses that can spit really well.’ But when I started to blossom is when I let go of anything gimmicky. I’m as goofy as I am. I’m as smooth as I am. I’m as funny as I am. I’m as serious as I am. I’m all those things. The totality of myself that I’m honoring is why I’m being embraced by hip-hop.”

Harlow kept getting bigger locally and released a series of independent mixtapes of increasing quality, eventually signing to Generation Now, the Atlantic imprint co-founded by DJ Drama, after his speed-rapping single “Dark Knight” led to a bidding war. He met Chris Thomas, who became his manager, before he graduated from high school. “I was like, ‘Hey, where are you applying to college?’ ” Thomas says. “And I remember him saying, ‘Oh, I’m not going to college. This is what I’m gonna do. This is gonna happen for me.’ And I was so taken aback at that. He already knew what was gonna happen, and his vision has all come to life.”

Photograph by Ryan Pfluger. T-shirt by Tommy Hilfiger. Overshirt by KOZHA. Jeans by Levi’s

A week before our Louisville trip, Harlow is staring at the tentative track listing for his new album on a whiteboard in the corner of a Los Angeles recording studio. He ticks it off, song by song: “Smoker. Smoker. Smoker. Smoker. Smoker. Smoker. Smoker. Smoker. Smoker. Smoker. Classic. This bitch got smokers!”

“It’s crazy how we, technically, need all of these shits to do what we’re really trying to do out here,” says Nemo Achida, Harlow’s A&R guy, co-producer, and sometime co-writer, who had a rap career of his own a few years back. “To really smack people across the face the way we want to, and put my boy on Mount Rushmore.”

In addition to BPMs and key signatures, each song is marked as either a “sometimes” or “always,” a metric that Harlow is convinced says everything about a track. “Nail Tech” is a “sometimes”; “Face of My City,” from his last album, is a “never,” he half-jokes. “Is it a song that you want to hear at any moment, in all moods,” Harlow explains. “Or is it meant for just one mood — for the club or before you work out? I have to get over my burning desire to make all of the songs on an album ‘always,’ because then it never cuts through. But I listen to fuckin’ Late Registration — so many ‘always’ on there. Nothing Was the Same? So many ‘always’ on there. But you can’t let it steer the ship.”

Harlow’s rising stature in hip-hop could probably be gauged by the team he’s bringing together every night in the studio: virtuoso keyboardist Rogét Chahayed, nominated for a Producer of the Year Grammy this year for work with Doja Cat and others (that’s him on that unforgettable keyboard intro to Travis Scott’s “Sicko Mode”), and onetime Timbaland protégé and West collaborator Angel Lopez, a wizard with drums and percussion. Over the course of six hours in the studio, Chahayed casually tosses off literally hundreds of musical ideas, coaxing Steve Wonder-worthy harmonica parts or a woozy New Orleans horn section or eerie choirs of voices from his keyboard. Achida functions as a sort of executive producer along with Harlow himself, guiding them to his favorite sections or adding his own drum ideas.

The main goal is to make sure that the songs develop musically as they go along. “We’re doing shit with the production to make you continue to listen to a song,” Harlow says. “That’s been the whole mission.”

Harlow doesn’t want too many details out yet about the songs or guest stars yet, but he does acknowledge that his team has been talking to Dolly Parton’s people about recording with her: “I want to put her on some hard shit,” he says.

While Harlow takes an endless phone call about the “Nail Tech” music video, the team improvises a hot beat from scratch, based on a foreboding two-chord sequence and a few notes sung into an iPhone mic. Harlow jumps on the beat when he comes back to the studio, recording a verse or two that he quickly abandons.

“I don’t always have something to say in every moment,” he says. “I have to search for a feeling that’s real. It’s different when you’re not a street artist because a lot of street artists come from an environment that is constantly producing stuff you can make a movie about. Or they just jump to a gun line. There’s weight on a gun line, no matter how frivolously or nonchalant they say it. I remember a Kanye interview while he’s making Graduation, and he says, ‘You know how hard it is for me to write these songs? I can’t just jump to a gun bar. Because I’m not a street artist, every line has to be compelling.’ ”

Eventually they turn their attention to a song called “Blade of Grass,” which has a moody instrumental intro before Harlow jumps in with an unforgettable first line: “Like a blade of grass wants sunlight/I just want that ass.”

They have Chahayed do take after take of a faux Stevie-harmonica intro, trying to fix the awkward way it interacts with the drums and the beginning of the vocals, until Achida suddenly suggests slicing out the intro entirely: What if they started with Harlow’s voice a cappella?

The idea catches on a bit before midnight, and the group ends up spending at least an hour making the change, devoting most of the time to obsessing over the exact spot the beat should come in. “Come in on ‘ass,’ ” Achida suggests at one point, to much laughter.

Once they finally get it right, Harlow is thrilled. “Bro, this shit is classic,” he says. “We just trimmed so much fat off this. It’s a rap record now. We need shockers on this bitch. We’re coming in trying to hold our dick on these motherfuckers.”

Soon, the evening seems to be winding down. “I think we should dead it,” Harlow says around 1:30 a.m. There’s some mumbling around the room: half day? Harlow smirks. “Unless . . . somebody’s feeling inspired,” he says. They end up staying for at least another hour and a half.

Photograph by Ryan Pfluger

This is Harlow’s imitation of the “serious part” of every interview he’s ever done: “So, you’re white . . . ” After a big dinner in a private back room of a Mexican fusion restaurant — Ciera, Tierra, Nemo, his trainer EJ, Jack’s parents, and his manager are all there — we head back up to 21c’s penthouse, just the two of us this time. There is, to be sure, white-rapper stuff to talk about.

But more broadly, especially after meeting his very proud, still happily married parents, it’s hard not to wonder: In the absence of any perceivable trauma, or even anything particularly missing in his life, what’s driving him? “I grew up with a lot of love,” he says, leaning back on his chair, one hand casually resting on his crotch. “I grew up with a pretty happy disposition. I’d say I had a great upbringing. So that’s a great question. It’s really a question I want to wrestle with with my therapist. Why do I care so much? Why am I so ambitious? But I just am. It’s me, bro. I wake up and I’m hungry. I think a lot of times you’re right, ambition does come from damage. But it comes from passion for me. I want to live the richest life I can. I just want to feel everything that I could possibly feel. I’m not satisfied with living, like, average life.”

Even though he’s quit drinking, Harlow might not be averse to some weed once in a while, except that it has a kryptonite-like effect on him. “When I get high, I lose my poise,” he says. “I lose a lot of what I like about myself. I think it’s a control factor, too. I lose a little control. I take pride in having my wits about me and being on point. Being quick, being thoughtful, making the right decision. Shit makes me subconsciously self-loathing. When I’m high I feel like I’m a piece of shit, and everyone knows.” Hallucinogens apparently have the opposite effect; he wrote some of the most swagged-out lines on the new album while “shroomed out.” If any other substances were involved in his songwriting, he’s not saying: “I don’t want kids to think that’s the key to be creative. I know a lot of kids listen to me.”

With or without weed, Harlow is paranoid about being “canceled,” though he can’t quite imagine for what. He can be sure, at least, that there are no recordings of him using racial slurs. “That’s one thing I never have to worry about, thank God,” he says. “I don’t say that shit [even] under my breath in my room by myself.”

The most serious incident of Harlow’s career involved his former DJ, Ronnie Lucciano, a.k.a. Ronnie O’Bannon, who is accused of killing a woman at a club night last May (O’Bannon’s lawyer has said it was self-defense). With criminal charges and a lawsuit pending, Harlow can’t say much about that one. “I was down for weeks off of that,” he says. “It’s definitely one of the darker things that I’ve ever faced.”

Tory Lanez and DaBaby both appeared on 2020’s “What’s Poppin’” remix, before each faced deeply tarnished reputations; Lanez has been charged with shooting Megan Thee Stallion, and DaBaby unleashed homophobic remarks. Harlow faced pressure to remove them from the song, which never made sense to him, especially since the incidents happened after they recorded with him. “I know I’m a good person,” he says, after a very long pause. “My character, my integrity are very important to me. And I think I’ve done such a good job that now I’m being forced to answer for other people’s actions. It doesn’t feel right as a grown man to speak for other grown men all the time. . . . One thing’s for sure, is that Megan got shot. And I wish her nothing but love and respect.”

Harlow is all too aware of one of the cringiest moments in rap history, when Macklemore not only apologized to Kendrick Lamar in 2014 for the positively deranged decision by the Recording Academy to give best rap album to Thrift Shop instead of To Pimp a Butterfly, but also posted his text to Lamar online. “I vividly remember that moment, and I vividly remember the reaction,” Harlow says. “Yeah, that’s hip-hop history right there. I don’t have any criticism of it, because you never know how someone felt in a certain moment. And what’s scary about the internet is you can make impulsive decisions, and they live on forever.”

For his part, Harlow is comfortable with gunning for the best-in-his-generation slot. But does he have the right to do so as a white man in a Black genre? “This is a question I’ve asked myself,” he says. “But at the end of the day, people could ask, ‘Is it right for you as a white person to rap?’ But people see I have an innate passion for rapping, so they don’t ask me that question. . . . There’s a competitive side to this, and honoring the competition makes it even more real and hip-hop, instead of me saying” — he affects a wimpy voice — ‘Hey, I shouldn’t have won that.’” He returns to that Macklemore moment: “That’s why they didn’t like that text, because it’s even more ‘I’m not as hip-hop,’ you know what I’m saying?”

Harlow smiles. “I’m saying, I love this shit so much that I’m gonna go out on that court and play as hard as you’re playing,” he says. “And we’re not gonna discuss if it’s OK. Let’s play ball.” It’s past 1 a.m. In a few minutes, Ciera and Tahira will be rejoining him. The movie rolls on. “I’m here to play ball.”

From Rolling Stone US