“Subdivisions,” one of Rush’s most beloved songs, is also one of their simplest. Geddy Lee’s insistent synth riff gives the track — a fan favorite from 1982’s Signals — a muted, almost drone-y quality. So you might hear it 100 times before you realize what’s going on just underneath the surface: That Neil Peart, the band’s brilliantly obsessive supergenius of a drummer, has gone to the trouble of crafting a different drum part for every single verse.

He starts the first one (“Sprawling on the fringes of the city…”) with a humble backbeat. Then, as Lee sings “in geometric order,” he switches to a busier, more lopsided pattern that almost seems to stumble along. The second time around (“Growing up it all seems so one-sided…”), he begins with a spare four-on-the-four bass-drum pulse, then moves (“Opinions all provided…”) to a kind of cyborg James Brown beat — devilishly syncopated and weirdly funky.

The variations continue from there: Verse three (“Drawn like moths, we drift into the city…”) features a cramped pattern interrupted by a weird, jutting fill, while verse four (“Some will sell their dreams for small desires …”) gallops away on a triumphant, slamming snare-kick groove.

Realizing what’s going on, you might wonder, is he simply showing off? Tossing out rhythmic Easter eggs for the drum-geek faithful?

But consider the song’s lyrics — written, like those of nearly every Rush song from 1975 on, by Peart himself. “Subdivisions” is an achingly poignant chronicle of the suburban teenager navigating cruel social hierarchies on one side (“In the high school halls / In the shopping malls / Conform or be cast out”) and soul-crushing sameness on the other (“Growing up, it all seems so one-sided / Opinions all provided / The future pre-decided / Detached and subdivided / In the mass production zone”). “Nowhere is the dreamer / Or the misfit so alone,” Lee sings, and Peart’s ever-morphing beats — set against the song’s cyclical, almost lulling form — are that misfit dreamer, railing against conformity, struggling to find a voice in a dreary and oppressive world. Like the Neil Peart aesthetic as a whole, the song’s drumming is at once profoundly nerdy and totally exhilarating.

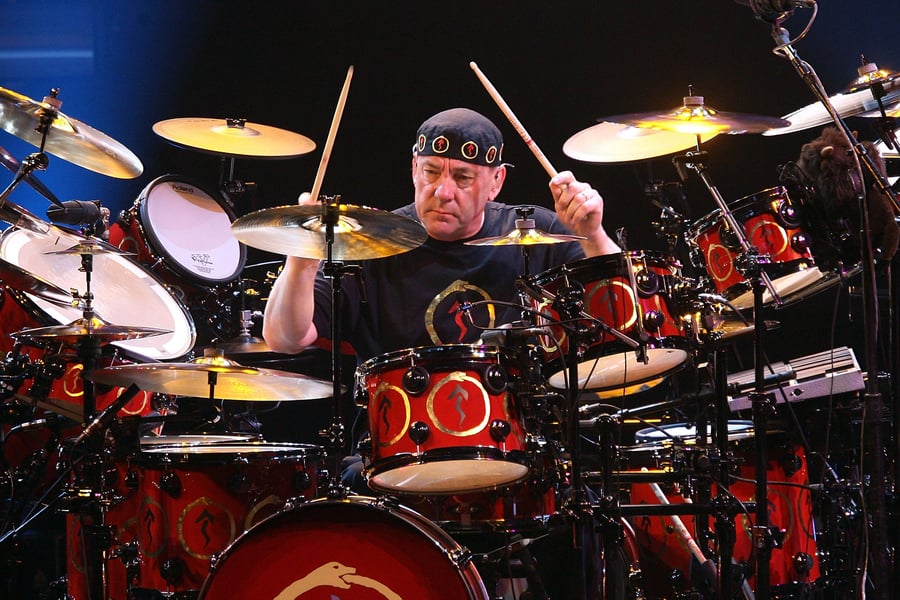

Am I, a die-hard Rush fan of 25-plus years, overthinking the significance of the beat swapping heard on “Subdivisions”? Quite possibly. But, I’d wager, no more than Peart himself. Rock has maybe never known a greater overthinker than Peart — who died this week at age 67 — a player and conceptualist for whom no detail was too minuscule to sweat. Consider the way, during his monster fill in the middle of “Tom Sawyer,” he takes a microsecond-long detour from his innumerable tom-toms to slam out an offbeat cymbal accent; how, during a pause in the overture section of sidelong 1978 epic “Cygnus X-1 Book II: Hemispheres,” he throws in a tiny ping on what sounds like a triangle; or how, during what seems like a straightforward rock groove on 1993’s “Animate,” he moves his right-hand stick from the outside to the inside of the ride cymbal with each note, creating a subtle shift in texture.

Before Peart — and since we’re overthinking, let’s clarify that it’s pronounced “peert,” not “pert” — all this fuss would have been anathema. (To many prog skeptics, surely it still is.) By the time Peart recorded his first album with Rush in 1975, the cornerstones of modern rock drumming had all been firmly laid down, mostly by British players taking cues from American R&B and jazz. For an aspiring drummer, there were many ways you could go: You could dig into a feel-good backbeat like Ringo or Charlie; you could gleefully trample the riff like Moon; you could channel the fluidity and fire of big band and bebop like Ginger, Mitch, Ian Paice, or Bill Ward; you could dial both the muscle and the funk way, way up like Bonham; or you could stylishly reconcile technicality and groove like Collins and Bruford. As different as they were, one thing all these players had in common was a fundamental looseness behind the kit. They all, in their own way, swung hard.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Peart was different. Watching him with the band in the early days, like on the “Anthem” clip below, he seemed steely and determined, almost grim. His playing rocks, without question, but it is a rock born out of concentration rather than abandon. He idolized Keith Moon, but in terms of approach, their basic philosophies of drumming, the two might as well have been playing different instruments.

Peart was not about feeling his way through the music; his approach was to get it all perfect ahead of time and execute prewritten, essentially unchanging parts with flair and excellence, almost more like a classical percussionist. (It’s ironic that in the lyrics for “Hemispheres,” Peart wrote about the struggle between Apollo and Dionysus for the soul of man, and the importance of finding a balance between the two tendencies, because in the vast majority of Neil Peart drum compositions, Apollo clobbered Dionysus every time.)

In the late Seventies, Peart’s style flourished along with Rush’s music, rising to meet the insane complexity of Lee and Alex Lifeson’s writing with equally high-tech invention. Check out, for example, the roughly 90-second outburst that ensues near the end of “Cygnus X-1 Book I: The Voyage,” a patch of prog whitewater that presages the entire genre of technical metal, and the busy, riff-gobbling style of drummers ranging from Dream Theater’s Mike Portnoy to Mastodon’s Brann Dailor.

But it was in the early Eighties, as Rush started to master more concise song forms, that the full extent of Peart’s mastery really became apparent. His parts on immortal hits like “Tom Sawyer” and “The Spirit of Radio” — which features a precison-sculpted ride-cymbal rhythm that would become one of his sonic signatures — remained extremely, sometimes outrageously, busy, but he started balancing that tendency with a real sense of economy and restraint. Check out how he gets out of the way of Lee’s voice during the verses of “Limelight” — a song where his lyrics wrestled with the vertigo of sudden fame — or how he lays down a crisp, minimal groove on Permanent Waves deep cut “Entre Nous,” one of the best songs ever written about the importance of space in relationships. I don’t think it’s an accident that his drumming uncluttered itself at more or less the exact moment his writing started tackling human emotion directly, without an extra layer of allegorical or sci-fi trappings.

Even where his signature busy-ness remained, as on “Subdivisions,” he was able to the serve the songs because, after all, he’d helped write them.

“There are a lot of reasons why I get away with being so active, especially how I got away with it in those days, and it was because of having carefully orchestrated drum parts that framed the necessary vocal parts of the song,” he told Modern Drummer in 2011. “I never got intrusive in that respect. And I know what the lyrics are and where the vocals are going to go. I don’t know how many drummers I’ve talked to that had to record a song when the lyrics weren’t written yet, and what a terrible handicap that is.

“I love the fact that not only are the lyrics written, but because I wrote them I know them,” he continued, with a laugh. “I know where I can punch up vocal rhythms and accents, for example. It’s really lovely to be able to do that. I think a lot of drummers are forced to play simpler than they’d like to, just not to take a chance on being in the way. It’s like a session musician thing — you’re supposed to be invisible. But in a band you’re supposed to express yourself.”

In the Eighties, that expression manifested itself as a deep investment in sleek pop rhythms. But Peart never stopped packing his drum parts full of tasty microdetails for fans to geek out over: the vibrant electronic-percussion flourishes in the chorus of tearjerking “Where did the years go?” anthem “Time Stands Still” or the sudden, unexpected rest that concludes the chorus of elegiac anti-teen-suicide track “The Pass.”

During Peart’s final two decades as an active drummer, he seemed to do everything he could to expand his drumming horizons, delving into the music of Buddy Rich and rebuilding his technique from the ground up with the help of midcareer mentor Freddie Gruber. As he told RS’ Andy Greene, that study gave him a “different clock” behind that kit and you can detect some added air and elasticity in his beats on 1997’s excellent, underrated Test for Echo.

But ultimately, he was not — like, say, Ginger Baker or Bill Bruford — a player who would ever really sound at home in a jazz, or even jazz-y, context. (Even unpacking how Gruber helped him loosen up his time on the instructional video, A Work in Progress, he often sounds like a middle-school science teacher running down the periodic table.) The bits of clunky big-band swing he’d throw into his epic solos at Rush concerts showed, again, that he simply had a different rhythmic orientation than the rock giants who preceded him — one that was uniquely suited to his band’s unapologetically brainy sound. Some players would cower before a passage like the choppy rhythmic morse code that opens 2007’s “Far Cry,” for example, but Peart just comes off like he’s shooting lay-ups.

On Clockwork Angels, Rush’s final LP and the first time they’d ever made a front-to-back concept album, Peart reserved most of his obsessiveness for the steampunk-inspired storyline. Drumming-wise, for the first time, he seemed to allow himself the luxury of relaxing a bit, maybe getting a little taste of how his Sixties heroes like Moon felt behind the kit. He enlisted producer Nick Raskulinecz — dubbed “Booujzhe” by Peart for the way that he would suggest drum fills with “wild physical gestures and sound effects” — to help him out.

“Rush songs tend to have complicated arrangements, with odd numbers of beats, bars, and measures all over the place, and our latest songs are no different (maybe worse — or better, depending),” Peart wrote on his website of the Clockwork Angels sessions. “In the past, much of my preparation time would be spent just learning all that. I don’t like to count those parts, but rather play them enough that I begin to feel the changes in a musical way. Playing it through again and again, those elements became ‘the song.’

“This time I handed that job over to Booujzhe. (And he loved it!) I would attack the drums, responding to his enthusiasm, and his suggestions between takes, and together we would hammer out the basic architecture of the part. His baton would conduct me into choruses, half-time bridges, and double-time outros and so on — so I didn’t have to worry about their durations. No counting, and no endless repetition. What a revelation! What a relief!”

The approach — i.e., Peart for the first time approaching drum recording with the Dionysian abandon that most other players take for granted every time they sit down at the kit — worked beautifully. It’s not like he suddenly started playing like a hardcore-punk drummer; Booujzhe’s assist seemingly allowed him to be his old always-in-command self, just a bit looser. On the album’s title track, he sounds staggeringly good, channeling his Eighties economy on the bouncy, borderline-funky verse, then reasserting himself as the king of high-prog ferocity once the tempo jumps and Alex Lifeson’s distortion kicks in. What stands out most about his playing on the album, from the shaggy groove of “BU2B” to the punishing uptempo verses of “Headlong Flight,” is its sheer heft and authority. Freeing up his brain seemingly allowed him to throw his whole body into these songs.

But as witnessed by anyone who saw Peart on the Clockwork Angels tour — or the triumphant R40 one that followed — onstage, he never let go of the reins, never cut corners on all those wildly elaborate parts he’d crafted over the years. Never stopped obsessing. In 2018 Geddy Lee reflected on the drummer’s retirement and why there would likely be no more Rush tours. “Neil was struggling throughout that tour to play at his peak, because of physical ailments and other things that were going on with him,” Geddy Lee said in 2018. “And he is a perfectionist, and he did not want to go out and do anything less than what people expected of him. That’s what drove him his whole career, and that’s the way he wanted to go out, and I totally respect that.”

For many, playing rock music is about relinquishing control, embracing chaos — its rebellion depends on some combination of sweat, spontaneity, and raw sexuality. But that wasn’t Neil Peart’s way. Straining against a future pre-decided, a life detached and subdivided, he found his rock & roll release, paradoxically, in organization and order. Not cookie-cutter musical forms, but gorgeously elaborate rhythmic constructions of his own making, crafted to fit the emotional contours of songs he himself had a hand in writing. As a musician, was Neil Peart unusually uptight? Maybe. Was he completely, wholeheartedly, unapologetically obsessed? Without question. That perfectionism is what set him free.