Thirty years ago this month, Madonna released one of the most fascinating records in her catalogue, I’m Breathless. Attached to her role as the nightclub singer/femme fatale in Warren Beatty’s 1990 film Dick Tracy, I’m Breathless wasn’t necessarily a proper solo album, but one of those “Music From and Inspired By the Film” projects that the world’s biggest pop stars always seem compelled to make (see also: Prince’s Batman or, more recently, Beyoncé’s The Lion King: The Gift). Meant to match Beatty’s exorbitantly stylized adaptation of the 1930s comic strip, I’m Breathless was a collection of big, brassy tunes that recalled the Prohibition era more than anything in the contemporary zeitgeist. It was a decisively dizzying left turn for an artist who’d already built a solid career out of them.

The year before, Madonna had released Like a Prayer, a critical and commercial smash, and a crowning artistic achievement to wrap up her remarkable run during the Eighties. Her cultural dominance was unparalleled; she’d brought a soft-drink conglomerate to its knees. But entering the Nineties, the one thing Madonna was not, was a movie star. It certainly wasn’t for lack of trying, but after a breakout turn in 1985’s Desperately Seeking Susan, her subsequent projects — 1986’s Shanghai Surprise, 1987’s Who’s That Girl, and 1989’s Bloodhounds of Broadway — had all been tremendous flops.

In a 1989 interview with Rolling Stone, Madonna wasn’t exactly willing to cede ground when asked if she considered herself a movie star: “Yes, if I could be so immodest to say so,” she replied. Though just a moment before she acknowledged the hurdles she faced in Hollywood: “I don’t really think they understand me well enough to think of me in any way,” she said. “A lot of them see me as a singer.”

That was all designed to change with Dick Tracy. The film had been a pet project of Beatty’s since the Seventies, and by the time Disney finally greenlighted the film in 1988, it seemed destined to be a summer blockbuster. Beatty would direct, produce, and star as the hard-nosed detective with the yellow cap and mac jacket; Al Pacino would play his nemesis Big Boy; and Madonna had secured the role of Breathless Mahoney, who falls hard for Tracy, tries to steal him from his girlfriend, Tess Truehart (Glenne Headly), and eventually turns out to be the conniving, merciless, faceless villain known as “The Blank.”

Like any proper Disney movie, music was a crucial component of Dick Tracy, and it ended up producing three separate albums. Beatty hired Danny Elfman to handle the score (album one) and singer-songwriter Andy Paley to make an official soundtrack (album two). He also enlisted Stephen Sondheim to pen several original songs, three of which were to be sung by Breathless; and Madonna — savvy as ever — used them to anchor her own new album, I’m Breathless.

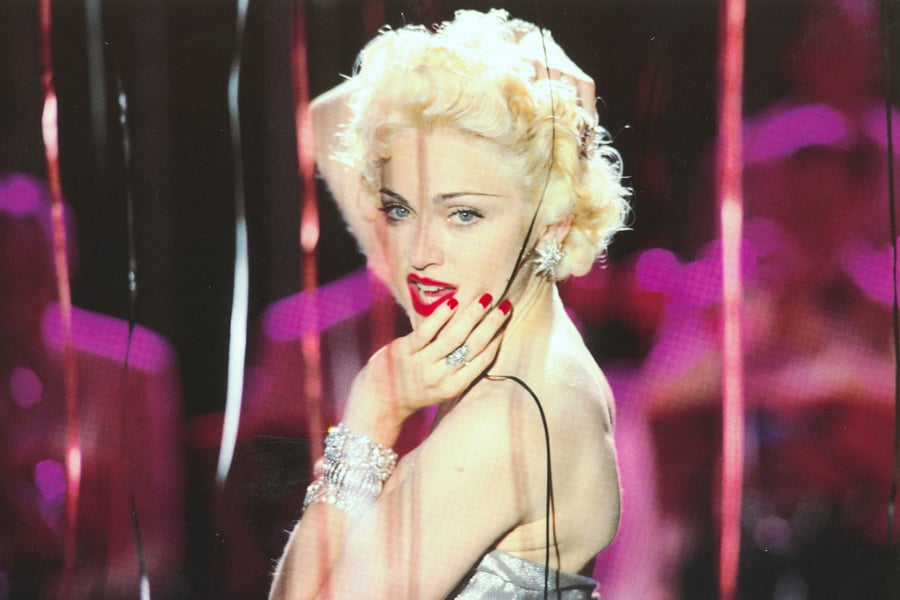

At the peak of her powers, Madonna could have easily recorded the three Sondheim songs for Dick Tracy and called it a day. Instead, the Queen of Pop chose to deliver a record of big-band jazz and musical-theater pastiche, cap it all off with one of her biggest hits ever, “Vogue,” and then make those songs a tentpole of her massive Blond Ambition Tour. Coming off Like a Prayer, arguably her most personal album to date, I’m Breathless could be viewed as a pivot to the comfort of character, but as much as the album is rooted in her Dick Tracy role, it simmers with a personal touch and tension that’s distinctly Madonna Louise Ciccone.

Madonna wasn’t Beatty’s first choice to play Breathless Mahoney — and she knew it. “I saw the A list and I was on the Z list. I felt like a jerk,” she told Newsweek in 1990. But with top choices like Kim Basinger and Kathleen Turner unavailable, Madonna managed to sway Beatty, and even agreed to work for scale, making just $1,440 a week on the film. Though as Forbes reported at the time, she did negotiate some extra points on the back end that certainly made it worth her while — to say nothing of the 7 million copies I’m Breathless sold worldwide.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

At some point, Madonna and Beatty’s working relationship became a romantic one. They dated for just 15 months, but the tabloid fodder was astronomical: Madonna had just ended her tumultuous marriage with Sean Penn; Beatty was one of Hollywood’s most prolific lovers; there were two decades in age between them; and he was directing and starring alongside her in an expensive summer flick with high expectations. The whole thing smacked of a publicity stunt. To suggest there wasn’t something mutually beneficial about it would be naive: Madonna wanted that Hollywood clout, and while Beatty could offer it, he was nevertheless coming off a massive flop of his own, 1987’s Ishtar. Considering that by 1990, he wasn’t exactly Clyde Barrow anymore either, some contemporary oomph to push Dick Tracy certainly wouldn’t hurt.

Madonna said as much herself in that Newsweek story: “Disney didn’t come to me and ask me to help market the movie. Let’s just say I’m killing 12 birds with one stone. It’s a two-way street. I’m not going to overlook the fact that it’s a great opportunity for me, too. Most people don’t associate me with movies. But I know I have a much bigger following than Warren does, and a lot of my audience isn’t even aware of who he is.”

But to assume their relationship was just an empty vessel for publicity feels unnecessarily jaded. It’s clear why it failed — just watch the famously private Beatty squirm every time he appears in Truth or Dare — but it also does seem like it was built on plenty of genuine mutual affection and admiration.

“I don’t know that there are many people who can do as many things as Madonna can do as well,” Beatty told Vanity Fair in 1990. “People who are in a positive frame of mind, who bring as much energy and willingness to work as Madonna does. She has, in this respect, a real healthy humility about the theater. I think this is a prime requisite to be able to function in theater — or, actually, in art.… As she goes on she will gain the artistic respect that she already deserves.”

Madonna’s relationship with Beatty wasn’t the sole force driving this moment in her career, but it is an important piece of it, and I’m Breathless feels not necessarily indebted to it, but crafted in its glow. Auteur that he was, Beatty was heavily involved with every aspect of production on Dick Tracy, including the music. In a recent interview with Rolling Stone, Patrick Leonard, one of Madonna’s go-to collaborators at that time, recalled a dinner with Madonna and Beatty to discuss ideas and reference points for I’m Breathless. Andy Paley — a go-to producer at Sire, Madonna’s label — says Beatty came to the studio on multiple occasions while he was working on the official Dick Tracy soundtrack, which the filmmaker wanted to feature all-new music that sounded as if it were released no later than 1939.

“Warren came to the studio and he played piano for the guys, he really got into it,” Paley tells Rolling Stone. “He would refer us to old records that he liked [such as Bob Wills and Fletcher Henderson]. He was so invested in that project.”

Along with being era-appropriate, the music for Dick Tracy had to fit its aesthetic, one in which the sets looked stripped from the Sunday funnies, every villain’s face was slathered in prosthetics, and Al Pacino could deliver 85 percent of his lines at a pitch and volume that still somehow didn’t feel half as over-the-top as everything else around him. Big-band arrangements may have been new sonic territory for Madonna, but big shows weren’t.

I’m Breathless came quickly, Leonard says. Usually, he and Madonna worked at a fast clip, but where Like a Prayer took a couple of months, I’m Breathless came together in only three weeks.

“It was like one-a-day for a little over a week,” he says. “I’d play her something, she’d write some lyrics, then go in and sing it. And I think in this case, many of those vocals were the final vocal. Then we just overdubbed the big band and orchestra in like one or two days.”

The three Sondheim songs, though — “Sooner or Later,” “More,” and “What Can You Lose” — were a different story, recorded separately from the sessions with Leonard and produced by another regular collaborator, Bill Bottrell. For decades, Sondheim had been composing music that could challenge even the top vocalists on Broadway, and Madonna, by her own admission, was far from the best singer in the world. In interviews from that time, she was open about the challenge his work presented.

“There’s not one thing that repeats itself,” she told SongTalk in June 1989. “It’s just unbelievable. When I first got them, I sat down next to him and he played them for me, and I was just dumbfounded. And then, forget about making them my own, just to learn to sing them — the rhythmic changes and the melodic changes — it was really tough. I had to go to my vocal coach and get an accompanist to slow everything down for me. I could hardly hear the notes, you know what I mean? So it was a real challenge. And they definitely grew on me.”

As Robert Christgau wrote in his review of I’m Breathless, “There are no doubt hundreds of frustrated chorines who could sing the three Sondheim originals ‘better’ than the most famous person in the world.” But Madonna put in the work and came to fully embody the tracks. The least gripping of the bunch is the tender duet “What Can You Lose,” and Madonna certainly holds her own alongside Sondheim vet Mandy Patinkin (who played Breathless’ pianist, 88 Keys, in Dick Tracy). “More,” however, feels practically prefabbed for Madonna — rich, fun, and gleefully gluttonous in the same way as “Material Girl.” And her navigation of the jazzy peaks and valleys of “Sooner or Later” is superb, a performance befitting the Best Original Song Oscar she helped Sondheim win.

As for the rest of I’m Breathless, Leonard says one reason it came together so quickly is that, unlike an “artist album,” for this one Madonna had “a script, a storyline, and characters in her mind that she could draw on.” Opener “He’s a Man” is most explicitly tied to the events of the film, as Madonna, as Breathless, tries to lure Dick Tracy away from his beat and law-abiding ways (“All work and no play/Makes Dick a dull, dull boy,” go the opening lines). But just as the three Sondheim songs appear in Dick Tracy as part of Breathless’ nightclub routine, much of the rest of the LP feels like what one of her sets would’ve sounded like. There’s the Carmen Miranda homage “I’m Going Bananas” (penned by Paley and Michael Kernan); the playful ode to soft boys everywhere, “Cry Baby”; the vintage torch song “Something to Remember”; and of course, that rollicking ode to spanking, “Hanky Panky.”

In many ways, I’m Breathless is a concept album and character study, though Madonna also found much to relate to in Breathless: “I’ve probably been preparing for the role all my life,” she told Interview in 1989. To that end, the album flirts with that space between person and persona, the most potent example being “Something to Remember.” It’s a devastating song about a devastating relationship, which Elizabeth Wurtzel, in her review for New York, said “sounds like a mournful but mature attempt to come to terms with her marriage to Sean Penn.” If that’s the breakup tune, other moments on I’m Breathless feel like they’re chronicling the ups and downs of the rebound with Beatty.

Listening to “Cry Baby,” it’s hard not to think of the way she refers to Beatty as “pussy man” in Truth or Dare, a nickname she expounded upon in a 1991 interview with The Advocate: “Warren is a pussy!… When I say ‘pussy,’ you know what I mean. He’s a wimp.” But then at the end of the album, Beatty appears on “Now I’m Following You,” a charming soft-shoe duet that Paley co-wrote with his brother Jonathan, Jeff Lass, and Ned Claflin. Beatty’s no belter, but he carries the tune with ease, and the chemistry between him and Madonna comes through in the song’s simple harmonies and head-over-heels lyrics: “My feet might be falling out of rhythm/Don’t know what I’m doing with them, but I know I’m following you.”

In Lucy O’Brien’s 2007 Madonna biography Like an Icon, session pianist Bill Meyers remembered the track coming together in just one take: “They’d paid for three hours, and the whole thing lasted 15 minutes,” he said. “I admire that. If you’ve captured the lightning in the bottle, why not?”

But even a song like “Hanky Panky” can say more about Madonna than Breathless. “I remember writing the music, and probably the first thing she sang was that,” Leonard remembers. “Right away, there it was, and not one to shy away from anything, it was on the list. I think things get blown up much bigger when they leave the studio. When we’re experiencing them, it’s just something to laugh about.” The song was born out of a Breathless line in the film (“You don’t know whether to hit me or kiss me,” she tells Tracy), paired with Madonna’s reading of the character as someone who “liked to get smacked around,” per a 1990 interview in Rolling Stone conducted by Carrie Fisher. But even as bawdy as a 1930s nightclub set could get, only the pop star who’d just left Pepsi out to dry would have the chutzpah see how far she could push Disney.

Speaking with Interview in 1990, Madonna acknowledged her penchant for being controversial, but she also found that particular word to be lacking. Instead, she framed the impulse this way: “It’s more like, ‘Hey, well, you know how they always say things are this way? Well, they’re not! Or they don’t have to be.’” When asked if she wrote her songs that way, Madonna replied, “I’m starting to. Especially on my last album [Like a Prayer]. And when you hear the Dick Tracy soundtrack, then you’ll know.”

In that same interview, Madonna revealed that she’d had to change some of the lyrics on I’m Breathless — “anything to do with sodomy, intercourse, or masturbation” — to appease Disney. But all the double entendres she managed to slip into the final version feels like a feat in and of itself. She flips one chorus on “He’s a Man,” to, “Cause I can show you some fun/And I don’t mean with a gun.” You can probably guess which word she stresses in this line on “Cry Baby”: “He acts like a real cock-a-doodle, he can’t even tell you why.” And on “Now I’m Following You, Pt. 2” — a contemporary dance-pop remix crafted by Kevin Gilbert — she coos what could’ve been a quip from her director’s cut of the movie, “Dick — that’s an interesting name.” And then, for good measure, the word “Dick” is chopped up and transformed to fit the song’s lead vocal melody. But Madonna’s purest presentation of her vision for I’m Breathless came on her Blond Ambition Tour. At each of her 57 shows, across three continents, Madonna would gleefully bump and grind with a Tracy look-alike and unleash a troupe of dancers wearing the yellow mac jackets and hats, with just black briefs underneath, for a routine of cancan lines and light striptease that’s wonderfully campy, sexy, and queer.

Arguably, the most sneakily subversive thing about I’m Breathless was the inclusion of “Vogue.” The song was certainly tacked on in part to satisfy the perennial music biz plea of, “We need a single,” but despite the vast sonic gap between it and the rest of the album, it doesn’t feel that incongruous thanks to the lead-in provided by the “Now I’m Following You” remix, and the song’s celebration of old Hollywood glamour. “Vogue” helped introduce underground ballroom culture to the American mainstream, and its legacy is a tangled knot of indisputable pop greatness and the issues implicit in a straight white woman using, and profiting off of, a culture and craft created by black and brown LGBTQ people, not to mention the mainstream’s willingness to seriously engage with that culture and craft only when it’s presented in this way.

The validity of these critiques, though, doesn’t mean one can’t still revel in the song’s brilliance, nor do they necessarily suggest anything malicious on Madonna’s part. She was steeped in New York City’s myriad music and arts scenes, and approached “Vogue” with a clear admiration and respect for the ballroom world. She was also, at the time, one of pop culture’s most prominent advocates for gay rights, someone who’d seen firsthand the devastation of the HIV/AIDS crisis and likely understood the many obstacles that still stood in the way of equality and justice. If nudging the needle of cultural opinion is one way toward achieving that goal, it’s hard to think of a more shrewd move than using a Disney movie as a Trojan horse for a song like “Vogue.”

Upon its release, Dick Tracy proved to be the blockbuster it was meant to be, grossing more than $162 million worldwide, picking up seven Oscar nominations, and winning three: Best Original Song for “Sooner or Later,” Best Makeup, and Best Art Direction. Madonna showed up at the 63rd Academy Awards not with Beatty, but with Michael Jackson, and performed “Sooner or Later” as if she were Marilyn Monroe, paraphrasing “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” to make a little barb about the Gulf War: “Talk to me General Schwarzkopf, tell me all about it!” she bellowed while windmilling a big fur boa. But Dick Tracy still didn’t exactly make Madonna the movie star she yearned to be. Her film projects over the next decade or so remained a mixed bag at best, with every A League of Their Own or Evita balanced out by a Body of Evidence or a Swept Away.

In the grand scheme of all things Madonna, the legacy of I’m Breathless is rather muted too. “Vogue,” of course, remains a concert staple, but per Setlist.fm, she hasn’t performed “Sooner or Later” or “Now I’m Following You” since Blond Ambition, and has only dusted off “I’m Going Bananas” for the 1993 Girlie Show World Tour and “Hanky Panky” for the 2004 Re-Invention Tour. And while the album surely ranks as a favorite for many fans, I’m Breathless hasn’t exactly achieved the status of a forgotten classic. But 30 years later, it remains a compelling snapshot of a pivotal moment in Madonna’s life and career, when the world rolled in ecstasy at her feet and she had the power to push it any which way she wanted, to mold it to suit her ideal.

There’s something about I’m Breathless that actually recalls a moment from another Warren Beatty movie, 1981’s Reds, his epic historical romance about John Reed and Louise Bryant. The movie features “witness” interviews from Bryant and Reed’s real life peers, and at one point, the author Henry Miller appears to offer this frank assessment of life in the early 1900s: “You know something that I think, that there was just as much fucking going on then as now.” Miller proceeds to ruin this perfectly astute observation with the qualification that he thinks sex has become more perverse and devoid of love, but the first part echoes something in Madonna’s remark to Interview about pushing buttons and boundaries. I’m Breathless allowed Madonna the chance to filter a staid Disney movie through her worldview. To say, like she so often did, “You know how they always say things are this way? Well, they’re not! Or they don’t have to be.”

A special note of thanks to AllAboutMadonna.com for its invaluable and extensive archive of Madonna press.