In 1975, Lou Reed gave Andy Warhol a BASF C-90 cassette. One side was a mix of live Reed songs recorded at recent tour dates. The other was an apparently homemade demo of a dozen songs based on his friend and mentor’s newly-published The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B & Back Again, published the same year. The idea, it seems, was to sketch out a kind of musical theater piece. The notion wasn’t new to Reed: The previous year, he’d tried unsuccessfully to enlist Warhol in creating a stage production of Reed’s Berlin LP, a project it would take him three more decades to realize. And just prior to Berlin, of course, he had the most consequential hit of his life with a song purportedly born of another unrealized musical — one based on Nelson Algren’s 1956 novel A Walk On The Wild Side.

The story of the “Philosophy Songs” tape came to light this fall when Cornell professor Judith Peraino published an essay called “I’ll Be Your Mixtape: Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, and the Queer Intimacies of Cassettes” in The Journal of Musicology. (Full disclosure: Peraino is a friend.) The recordings had been but a rumor among Reed superfans, and the existence of an actual tape of them in the Andy Warhol Museum archives in Pittsburgh made news internationally, in spite of the fact that almost no one could hear it.

The museum’s all-knowing late archivist, Matt Wrbican, was well aware of the tape before Peraino happened on it. But due to access and copyright restrictions, it hadn’t been written about until the author gained access to the recording, recognized its importance, and gamely worked around the restrictions. In the essay, she broadly described 12 songs played on acoustic guitar, rudimentary folk and rock riffs with audible traffic noise in the background; on one of them, she noted a boogie groove resembling “I Wanna Be Black,” a then-unreleased song Reed had been performing live (a version appears on the tape’s flip side). Peraino noted lyrics that touch on ideas from Philosophy and other Warholia, among them the presentational heroics of drag queens (“ambulatory archives of ideal moviestar womanhood,” as Warhol wrote in Philosophy), fame, success, and sex, plus reflected stories and gossip from Warhol’s circle, which Reed was still part of. Assorted signature Warhol expressions (including the notion of a “put on”) are referenced, ditto a story about his dog taking a shit in the aisle of his local Gristedes grocery, the conceit of a Warhol doll that does nothing when you wind it up, plus assorted gripes and snipes — a “shocking tirade of bitterness and accusation” towards the artist, as Peraino fairly describes it — capped by Reed’s apologetic authorial endnote.

It’s the stuff of compelling psychodrama. And while the version of the tape in Pittsburgh remains off-limits to the general public, Peraino also connected the dots to an apparent “Philosophy Tapes” fragment, available for anyone to hear on-site at the New York Public Library of the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, which opened its own Lou Reed Archives earlier this year — a veritable motherlode of Rock‘n’Roll Animal history and ephemera. Apparently part of a messy work tape including a portion of The Eagles’ One of These Nights LP, the fragment is illustrative (and not just in the revelation that Reed might’ve been an Eagles fan). There’s an acoustic guitar strumming beneath possibly improvised lyrics, full of playful word repetitions, and sung in a gentle voice that more than anything else recalls Reed’s latter-day work with the Velvets. It’s the sound of a master storytelling songwriter at work.

Whether the “Philosophy Tapes” or any of the unissued recordings in the Reed Archives will ever see official widespread release is an open question. At one point, there was talk of a Bootleg Series akin to Bob Dylan’s ongoing reissue project on Legacy, which also controls much of Reed’s back catalog. But in the meantime, coincidentally enough, there’s been a flood of Reed-related archival activity to accompany Peraino’s work.

A is for Archive: Warhol’s World From A to Z (Andy Warhol Museum/Yale University Press) is a massive achievement that the aforementioned Matt Wrbican completed shortly before he died in June. The book, with an insightful preface by Blake Gopnik (whose forthcoming Warhol bio promises to be a major event), surveys a series of exhibitions and projects curated from literally hundreds of thousands of Warhol’s personal items, drawn from the 610 storage boxes known as his Time Capsules and other sources. Surprisingly, the volume doesn’t dwell much on the Velvet Underground, whom Warhol mentored and “produced” in their early days. But the unpacking of gay porn magazines, tape recording experiments, and telephone obsessions, the mask-wearing and dress-up adventures (drag, clown, zombie), the New York nightlife addiction, the close friendship/working relationship with Billy Name, the gleeful cultural button-pushing, the faux-naif/primitive interview poses, the mentoring of younger artists, the relentless work ethic, even the obsessive archival documentation-cum-hoarding — all shine light on Reed’s own obsessions and art practices, and the New York City petri dish they grew in.

The framing of the latter is the great achievement of The Velvet Underground Experience (Hat & Beard). Basically the exhibition book for the show that opened in Paris in 2016 and occupied a pop-up space on Broadway for a few months last year, it spends many of its photo-rich pages depicting New York’s fertile 1960s art scenes, at whose nexus the Velvets pitched their tent. Spreads are dedicated to filmmakers Jonas Mekas and Barbara Rubin, forebears of the experimental film scene the Velvets soundtracked; Allen Ginsberg, figurehead of the New York poetry scene Reed was inspired by and participated in; and La Monte Young, the avant-garde composer who mentored John Cale and whose sound profoundly informed the Velvets’ own. There’s also a wealth of primary-source material involving Warhol and the Factory crew, including Velvets collaborators like poet Gerard Malanga, multi-media artist Danny Williams, and of course Nico, plus other band influences like actress Candy Darling, muse of multiple Reed songs. Curated by Carole Mirabello and Christian Fevret, longtime editor of the touchstone French music magazine Les Inrockuptibles, the show deserved a longer and wider U.S. run than it got; hopefully the book will inspire a rerun.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

A deep dive into what remains for some the supreme Velvets LP, their self-titled third album, came out of a collaboration between three of the world’s most devoted Velvet Underground archivists — M.C. Kostek, Alfredo García, and Ignacio Juliá. I Met Myself In A Dream… This is the Story of the Third Album (The Velvet Underground Appreciation Society) is a limited-edition book centered on photos taken by Sandy Schor during and around the 1968 recording sessions. Intended as publicity stills and album art, the images have great intimacy: Reed tuning a 12-string Gibson hollow body; the band set up behind ratty padded sound baffles, preparing to record in real time; and in-studio smoking breaks (Mo Tucker seems a Marlboro gal). Shots illuminate Reed’s affectionate relationship with Tucker. In one, they grin at each other, maybe the tambourine they pass between them. In another, the band poses outdoors in a verdant wood, Reed very high-Sixties in velvet slacks and a flowered, ruffled blouse of sorts, doubled by Tucker in a wide collared man’s shirt and jeans. In portraits, Doug Yule looks soulful in paisley; ditto Sterling Morrison, in one photo almost literally hugging a tree. The book also documents the album’s physical release, marketing material, and a startling array of obscure press notices (about the only kind the band got at the time). At the tail end of 1968 — after the departure of John Cale and the souring of the band’s relationship with Warhol, in the wake of the King and Kennedy assassinations and the Chicago and Washington riots — the third album was born in tremendously dark times, not unlike our own a half-century later, and Reed’s music responded accordingly. “I’ve gotten to where I like ‘pretty’ stuff better,” he told his frenemy Lester Bangs, in a quote used in the book’s excellent introductory essay. “You can be more subtle, really say something and sort of soothe, which is what a lot of people seem to need right now.”

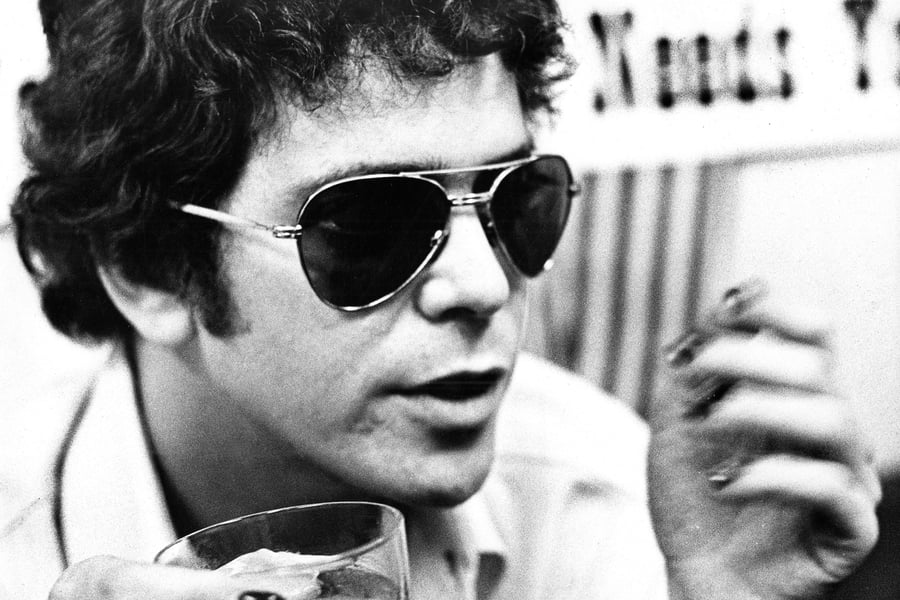

There’s not a lot of soothing going on in My Week Beats Your Year: Encounters With Lou Reed (Hat & Beard). Like Warhol, Reed made press interviews into performance art — and despite his legendary loathing of the process, he was a master of it. Curated and edited by writers Michael Heath and Pat Thomas, the book is a greatest-hits compilation of Reed’s more entertaining, illuminating, nasty, wiggy, bullshitty, warm, and generous conversations, and if it’s inevitably incomplete, it’s admirably representative, with plenty of classics. Yes, there’s an installment of the legendarily pathological exchanges between Reed and Bangs (the 1973 Creem magazine piece “Lou Reed: A Deaf Mute In A Telephone Booth”), and a pair of his livelier interviews with this magazine, including a vivid 1976 throwdown with writer Timothy Ferris. In the latter, Reed embeds an interview he did himself (apparently discussing coprophilia with a trans sex worker on a recording) into the conversation with Ferris; he goes on to dismiss Bob Dylan’s career output almost entirely (a position he’d later reverse, if he ever truly held it), then waxes ecstatic about Neil Young’s guitar work on Zuma (“excruciatingly beautiful … it made me cry”). Elsewhere, he speaks directly about queerness, Metal Machine Music, tai chi, the realities of earning a living as a musician in the 21st century, and much else. It’s sad he’s not here to weigh in on our current cultural moment.

Last month, the Reed lyric anthology Pass Thru Fire was reissued as I’ll Be Your Mirror: Collected Lyrics, expanded with an essay from his wife and soulmate Laurie Anderson and an introduction by Martin Scorsese (who notes that Reed auditioned for the part of Pontius Pilate in The Last Temptation of Christ, a role that ultimately went to his pal and occasional rival David Bowie). There’s still more on the way. In the wake of last year’s poetry volume Do Angels Need Haircuts?, Anderson is preparing a volume of Reed’s writings that he’d begun before his death but never finished, on tai chi, a practice that profoundly shaped his later life. And Todd Haynes, director of the recent interrogation of corporate America, Dark Waters, has been working on a Velvet Underground documentary for some years now, which should be revelatory. All this seems fitting. Periodic creative flippancy notwithstanding, Reed’s intention was always to make art for the ages. As it turns out, he did.