He came down at the same time every day. At 11 a.m., the elevator in the lobby of the Hilton in downtown Nashville would open to reveal Little Richard, looking stage-ready — bouffant wig, sunglasses, full makeup, sequined jacket, sparkling boots — and being pushed in a wheelchair by his son, Danny. As the pair made their way across the floor to their gold Cadillac Escalade waiting out front, tourists would approach Richard, and he would hand them a pocket-size religious book with his photo inside. Occasionally, he would ask Danny to wheel him over to the piano, where he would play a few notes of a blues song or one of his own. When the crowd started getting too big or the phones started coming out, he would cut off the performance.

It was an open secret that Richard lived at the Hilton, though even some of the biggest artists in town weren’t sure if it was a rumor or the truth. Richard moved from Los Angeles to Tennessee in 2003 to be closer to his sister. He and Danny, whom Richard had adopted at age 14 in 1984, first moved into a house in Lynchburg, the home of Jack Daniel’s, but they quickly got bored living out in the country. The Hilton wasn’t the most discreet location — just across the street from the Bridgestone Arena, it was often packed with tourists — but Richard didn’t mind. He personally worked out a deal with hotel management to let him move in and pay by the month. “Everything was there for him — room service, security,” says Danny, 49. “I guess he just liked to come out to fresh people every day. He was excited, making people happy.”

Those brief appearances in the lobby were just about all anyone saw of Little Richard in his final years, before his death of bone cancer at age 87 on May 9th. After more than 60 years as one of music’s loudest and most hardworking performers — a run that stretched from the dawn of rock & roll through his years as a TV personality popping up everywhere from Full House to Baywatch — he stopped playing shows in 2013 and pulled a dramatic disappearing act: No new music, few interviews, not many visitors. Even Paul McCartney had a hard time setting up dinner, Danny says.

After making their way through the lobby, Richard and Danny would meet their driver outside and start their errands for the day. That meant making the long drive to Lynchburg, where Richard still kept a second home, so he could check his mail. Though he could easily have had his mail forwarded, it was a good excuse to get outside — a recommendation from Richard’s doctors after he had hip surgery in 2009. Along the way, they’d stop at the bank, the post office, or a fast-food spot like Chick-fil-A, Richard’s favorite. “180 miles a day,” Danny says. “90 there, and 90 back.”

Richard told a lot of stories about the old days on those car trips. Sometimes he’d talk about playing the chitlin circuit in the early 1950s, or mention an old memory of the Beatles or the Stones. When he was younger, Richard was known to get heated talking about how he was first, how the artists he influenced got rich playing rock & roll, about how McCartney didn’t thank him when he got his Grammy Lifetime Achievement award. Now, Danny says, the bitterness was gone: “Oh, he gave up on that. He came to the reality of what it was: That’s his life. In the later years, he was at peace with it.”

In the early Eighties, Little Richard moved into a different hotel: the Hyatt on L.A.’s Sunset Strip. He had spent nearly a decade away from rock & roll, working as a traveling salesman for Nashville’s Memorial Bibles International, on a multiyear “country-wide evangelical campaign,” where he preached the Ten Commandments at churches around the country and denounced his sinful past. But Richard needed money. He published an authorized biography, The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Quasar of Rock, which he promoted with a huge press tour (in an appearance on MTV, he called Prince “the me” of 1984). It was time to start being Little Richard again.

This era was also important for another reason: It’s when Richard adopted his son. Danny Jones’ memories of the singer go back to the second grade, when Little Richard would drive up to Danny’s mom’s house in South Central Los Angeles. “All the kids would be waiting for him to come over,” he recalls. “Whenever he did, he’d have a bag of coins, and he’d throw it up in the air and we scrambled. Oh, man, we got some money!”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

When he came into Danny’s life, Richard had just retired from rock & roll for the second time, giving up his $1,000-a-day drug habit to fully dedicate himself to the -Seventh-day Adventist Church. He found a friend in a fellow parishioner, Creola Jones, Danny’s mother. “When he started getting really deep back into the church at that time, she was really nice to him,” says Danny. “It wasn’t about him being Little Richard or anything like that. Just a brother in Christ.”

Richard became a constant presence at the Jones home. “He was very low-key, and very humble, believe it or not,” Danny says. The singer became a more important figure to Danny in his teens, especially after his father’s death in 1982. Richard sang at the funeral, and Danny remembers going to watch Richard preach at an L.A. church. “It was amazing,” says Danny. “He would never say anything to me about whatever I was doing. He would just always encourage me. . . . I had six sisters and three brothers, living in a poor neighborhood, doing whatever. My mom asked him: Could he take care of me? Because she didn’t she want me turning out like the rest of my -sisters and brothers, and he agreed to it.”

After a handshake adoption — no paperwork — Danny moved into the Hyatt, where Richard had a two-room suite. He would live with Richard for the next 36 years. “Parenting for him was: He would say something to you, and you had to figure it out,” says Danny. “He would make statements like, ‘You control the money, don’t let the money control you.’ As a kid, you don’t really know what that means, but as life goes on, you figure it out.”

Danny laughs remembering the time he had a hernia operation, and Richard suspected the teenager was pretending to be sicker than he was. Determined to catch him in a lie, Richard told him the front desk was calling: “He’s like, ‘Hey, there’s some girl downstairs to meet you.’ So, of course, I rushed down there real quick. They said, ‘Nobody down here to see you, what are you talking about?’ I come back up, and he’s just looking at me, shaking his head. I was like, ‘Wow, he got me once again!’ ”

Starting in the late Eighties, Danny joined his father on the road, where he saw a different side of Little Richard. “You had no idea what you was gonna get,” Danny says with a laugh. “He might say or do anything.” Richard’s longtime agent, Dick Alen, who worked with the singer on and off for 40 years, recalls a lot of “confusion” on the road — like the night Richard refused to go on because a state-owned venue wouldn’t allow his team to hand out religious books to the audience (“Richard said, ‘No Bible, no Richard’ ”). There was the time Richard landed in Toronto to play a baseball stadium, and the promoter brought him to a presidential suite that wasn’t good enough for Richard. “They told me they wound up walking up and down the hotel going through five different suites before Richard found one that pleased him,” says Alen.

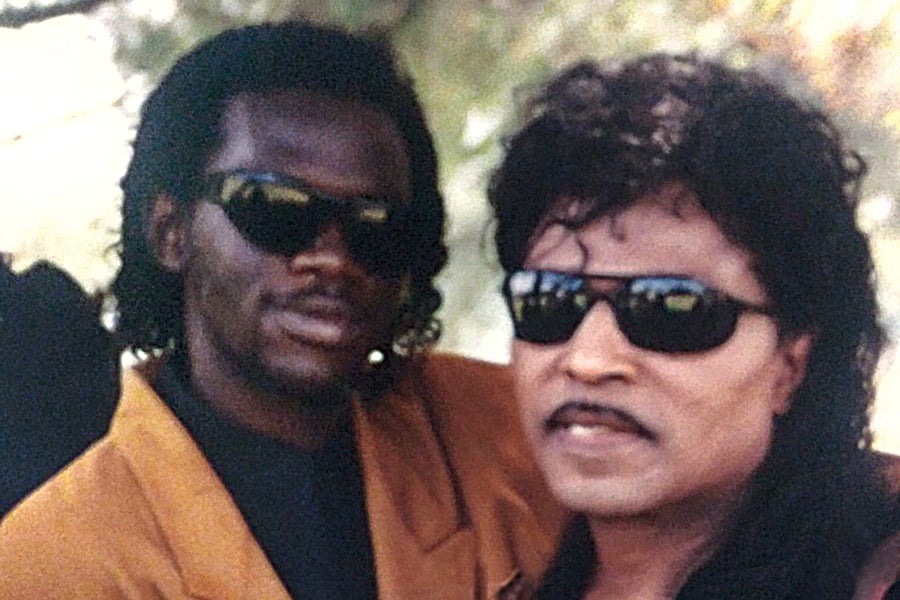

Little Richard with Chuck Berry and agent Dick Alen, who worked with both artists for decades.

Courtesy of Dick Alen

Richard’s competitive streak came out on the package tours he did with Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis beginning in the Nineties, when the three musicians realized that the money was much better when they played together. Though Richard called Berry his favorite rock songwriter, the two “had a rival thing,” says Danny, thinking back to a run of shows in Brazil, where the two artists agreed to alternate opening and headlining sets. The first night went fine, with Richard opening for Berry, but trouble started on night two: “Chuck rolled up and said he ‘ain’t opening up for no amateur,’ ” Danny says. “So he left, and Richard went out there and did a bunch of Chuck songs, and did his songs. He rocked the house. Like I say, you never know what you’re gonna get, anyway. The comedian? The preacher? The talker? The jammer? . . . His energy was unmatched. You’re trying to blow the roof off every night, and that’s what he did.”

Last spring, Tom Jones was on tour in the U.S. He had a day off after a show in Florida, and he knew how he wanted to spend it: by thanking his rock & roll heroes. He kept his private plane for the day so he could fly to Memphis to see Jerry Lee Lewis in the morning. In the afternoon, he’d swing through Nashville to visit Little Richard, who he’d known since 1965, when Jones made his first trip to L.A., to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show.

The day went well until Jones showed up at the Hilton. Though Richard had told him to come by, the front-desk clerk said that Richard was not expecting any guests. Danny came downstairs to apologize, too, but Jones persisted until they let him call Richard’s room. “Richard made it out like it wasn’t him that it was talking,” says Jones. “He said, ‘No, Richard is not seeing anybody, he is not feeling good,’ ” says Jones. “I said, ‘Look, Richard, it’s me! Don’t try to say that you’re somebody else, when I know it’s you talking!’ ”

The people around Richard were used to this behavior. Richard had become increasingly reclusive since giving his final concert on March 30th, 2013, at Las Vegas’ Orleans hotel. Though Richard smiled as he tore through classics like “The Girl Can’t Help It” and “Tutti Frutti,” he was in deep pain, the result of complications from his 2009 hip surgery. After the concert, Danny says, “He told me he wasn’t going out no more. He said it wasn’t worth it to him anymore. His hip was bothering him, and he just wasn’t feeling it. I told him, ‘That’s your career. Whatever you want to do, I’m with you.’ ”

Along with concerts, other things were off the table, too. In his final years, Richard turned down offers for interviews, feature films, and stage musicals, perhaps because he struggled with getting old and competing with the fiery image of his younger self. “He said music is different now, it’s only going to sell so much,” Danny says. “He said his legacy was already cemented. He didn’t want to diminish what he already started.” Religion played a big part in his decision to withdraw from the world, too. While the singer dressed up when he went out on his errands — “He was always Little Richard, in character” — he was a different person in private, reading the Bible in his hotel room.

Danny sees one Friday night in 2016 as pivotal. He and Richard were in their hotel room, beginning the Sabbath the way they usually did: watching religious videos on YouTube. One preacher made a point that resonated with Richard. “He said, ‘In the sanctuary, if you’re wearing flashy stuff, you’re taking attention away from [God],’ ” Danny recalls. After that, when Richard left the hotel room, he often went out with his white hair, no wig; conservative black suits; and house shoes with praying hands on them. “He said, ‘You can’t serve two masters,’ ” Danny says. “He changed everything. He just started being Richard Penniman again.”

Tom Jones finally ended up getting up to Little Richard’s room last year, after he promised the singer there would be no photos. He found Richard in bed in a nightshirt and no makeup. Still, Jones thought he looked good: “I said, ‘Richard, you don’t need the bloody wig. You got hair!’ And his skin was unbelievable. I said, ‘You don’t have a wrinkle in your face.’ He said, ‘That’s that Indian blood, Tom.’ ”

They talked for an hour. Jones brought up a 1964 TV special in Manchester, England, where Richard sang with the Shirelles — “If you want to see Little Richard at his best, that’s the one you wanna see” — and Richard’s 1969 appearance on Jones’ variety show, which only happened after Jones fought with the TV network. “He remembered everything,” Jones adds. “He was smiling and lit up.”

Before Jones left, Richard gave him a signed picture of himself from the Fifties. “He said, ‘I don’t look like I did in this picture,’ ” Jones says. “I said, ‘None of us do, the ones of us that are left. We all got white hair.’ It was lovely. He wasn’t bitter. He was happy, and that’s what I remember.”