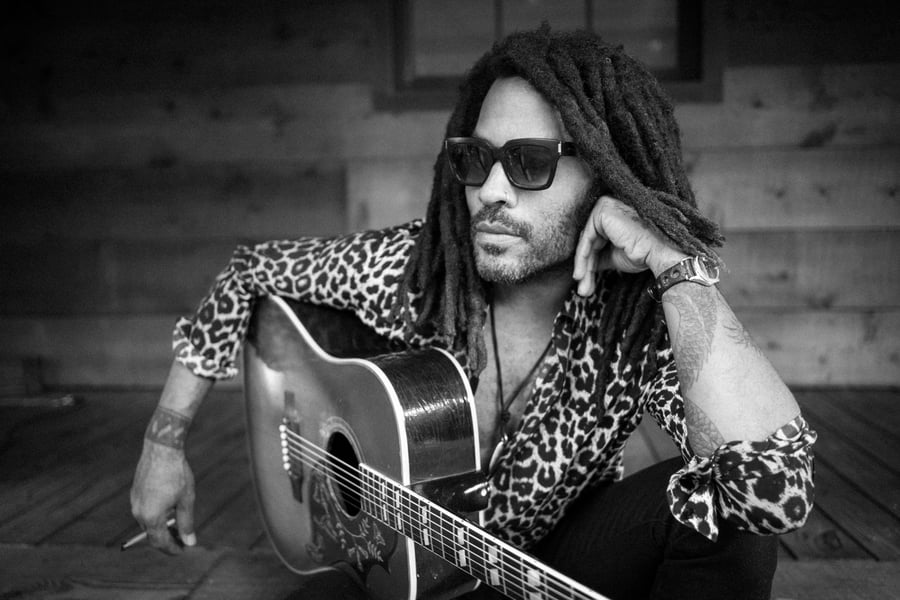

After the pandemic began spreading in early March, Lenny Kravitz left his Paris home and decamped to his retreat in Eleuthera, a small island in the Bahamas. Rather than touring the world and promoting his new memoir, Kravitz has been living the simple life, growing his own food and using trees as makeshift workout benches.

Kravitz has been in a reflective mood thanks to the memoir, titled Let Love Rule. It’s the first of two planned volumes, covering his life up until the release of his 1989 debut album. With little rock-star hedonism or stereotypical tales of excess to speak of — expect that in Volume 2 — you’re allowed to be skeptical. But the memoir is a fascinating look at Kravitz’s lifelong dualities. A biracial kid, the son of an NBC News producer dad (Sy Kravitz) and TV actress mom (Roxie Roker, of The Jeffersons), he shuttled between Manhattan and Brooklyn before moving to Los Angeles, where he felt equally at home in a Beverly Hills mansion and in goth, New Wave, and stoner/skater subcultures.

“I’ve always said that I love the extremes,” Kravitz says. “It’s the middle that I don’t do very well. Of course I can do it, but it’s not as appealing to me. I don’t get an energy from that. I feed off of the extremes.” The 56-year-old artist spoke to Rolling Stone from the Bahamas about the memoir, the pandemic, and slowing down.

Do you find it easier or harder to find creative inspiration during quarantine?

It’s been a really quiet, creative time. To be honest, when we are not in this situation and I’m down here creating, I realize that I’ve been quarantining my whole life. When I come down here, that’s kind of what it is. You’re around just a few people. The only difference is that you can go into the village [and] into the settlement and hang out with folks and go sit at a bar or restaurant and talk with the people. I miss that. But otherwise, this is kind of how I live all the time when I’m here.

Do you find it harder to find inspiration as you get older, or does age not play a factor?

I don’t deal with this aging thing. The numbers go up, but I’m still just as hungry and motivated and inspired as I was in the book. When I walk into that studio, it’s still magical to me. I never take it for granted. Being here enables you to hear yourself in a very clear way because you’re in nature. Because it’s so quiet. Because you’re somewhat isolated. It’s always been a great place for me to be creative. But, yes, I’m still in that place, man, thank God. I wouldn’t do it otherwise. I do know artists that as they continue doing this for years, I’ve seen folks get jaded [and] tired. They don’t want to be in the studio so much, and I have not experienced that.

Why a memoir now, and why break it up into two parts?

Well, I never thought about writing the book. I don’t think that my life is that interesting. [But] I’m glad that I did because writing this book was the best form of therapy I could have ever taken. This was a story about me finding my voice and I didn’t want it to be about stardom or fame. The second book will be a far more difficult book to write. Things got intense, but I think that [writing] it will provide the same level of therapy [and] a lot will be healed.

I was shocked to read that after you caught your father cheating on your mother, he told you, “You’ll do it, too” before he was kicked out of the house.

I was about 19. It was quite a deep statement at a time where I believe my mother wanted him to say something that would have benefited me. “This was wrong. I want you to understand and I’m sorry.” And he just went there. As hardcore of a statement as that was at that moment, I didn’t realize how deeply that had penetrated my being. But when I look back at it, I can understand now with new eyes and without judgment that he was just speaking what he thought was his truth.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

His father had done similar things and he was extremely angry at his father for that. And then he repeats the same sort of behavior, and then I guess he figured this is some kind of chain that can’t be broken. “You’ll do it, too, like he did [and] like I did.” It’s really sad and really intense and I had to deal with that years later.

You said the first thing that came to mind was the gun your father kept hidden in his closet.

I’m sure it was a dramatic thought of an angry teenager, because would I have done that? No. But I had that side of me that I could get angry quick. And I was so angry at him and I was so hurt, because I’m a mama’s boy, right? I adore my mother and I knew that that gun was in the closet to protect the house. But that’s where my head went. I remember telling my mother, “If you don’t get that [plane] ticket right now [to fly me out of L.A.], somebody might die.” Again, that’s an angry teenager, but that’s how I felt.

How do you think that event affected you later in life?

It definitely raised questions about commitment, and could I do that? But I spent some years working on getting that out of me. What was beautiful was that instead of seeing my father as my father and what he had done to me or to my mother, I saw him as a character. Because once you’re writing the book, everybody’s a character and you’re trying to put all of these things together. I got to see him as a man who was just trying to find his way to live through this experience with what he had, and what he had in some areas was limited to what his father did with him.

All of a sudden, all the judgment fell away and my love even opened up for him in writing the book. I ended up really liking him and understanding him and whatever was left of the anxiety, judgment, [and] hurt just disappeared because I accepted him as a human being … I love my father and I loved him more after writing this book. We made peace before he died.

You said in a video in March that “We’re all one; we’re one human race,” which has been an overarching ethos for you. There’s often a sense of utopianism in your work. Has that been harder to maintain with everything that’s happened this year?

No. It’s getting more intense. It’s getting more challenging. I know that we have the ability to come together; we’re just stuck in our horrible ways. I have remained positive through this. I’ve had days where I have to fight the depression coming on, because it’s just so sad how we treat ourselves and our planet. And to just see how backwards things are going. I saw the people before me fight for the things they fought for. If my grandfather was alive now to see to see what’s going on, he wouldn’t be able to handle it. I know we have the ability, but we have a deep hole to dig ourselves out of right now. The system needs to be completely torn apart and rebuilt.

Four years ago, you said, “Love has to be the final outcome of every situation.” Given the social unrest over the past year, is there ever a space for violence as a rebellious act to bring about social change?

I see why people get violent, and I understand it. That’s not my way; I want to take action through fighting those things, but not through violence. But do I understand the violence? Yes. Do I ever feel violent inside? Absolutely. It got to the point [where] I was watching all these videos where black men and women are being shot and I just couldn’t do it anymore. It brings out violent feelings.

In the end of the book, you write, “The life of a rock star is equal measure a beautiful blessing and a perilous burden.” What’s the “perilous burden” and how has that shaped how you relate to people?

I wasn’t prepared for what was to come. Even though I’d been around fame and I’d watched my mother deal with it in a very graceful way and I was around Zoe’s mother [Lisa Bonet] and watched her deal with it…. I was raised a very down-to-Earth person, but when the [first] record came out and the dynamic of fame came in and the music was playing all around the world, people’s attitudes toward me changed. I wanted to remain that same person that I was, but I had to take a real lesson in, how do I keep my spirit, but at the same time protect myself from people who are now seeing me as this thing and what they can get from being around me? I did remain open for the first couple of years and then, you know, things happened.

You told us in 1994, “I’m not a hippie. I’m just a person who likes what he likes and plays what he likes. Look what happened to the hippies. The majority of them are now the assholes that are fucking running everything.” Do you still feel that way?

That was the Nineties. I saw a lot of folks and friends of my parents — people that were hippies — [who] went on to become corporate yuppies and the whole nine. But that’s life. We change. “Hippie” is such a specific word. I guess you could say I’m still a hippie, whatever that’s supposed to mean. I’m into peace and love. I’m into nature. I’m into gardening. I’m into music and art. Whether it’s hippie or bohemian and whatever you want to call it, I do live that lifestyle. But I guess then, when I was saying “I’m not a hippie,” I didn’t want to be boxed into [that].

What was your personal definition of success when you first started, and how has that changed as you’ve gotten older?

My definition of success was that I was really proud of the albums and of the recordings. But I didn’t care that they were hits or they sold. I never went to one awards ceremony where I got the award. I remember one night I was in Paris. It was late at night [and] I was coming out of the club Les Bains Douches and I was in the back of some car and somebody called me and said, “You won the Grammy for…” I was like, “Oh, yeah, that’s cool, man. Great.” And I hung up and took another hit off my joint. I missed some moments where I should have been smelling the flowers. And so I’m now at a place in the last few years of my life where when I have any kind of success, I stop and I take a moment to take it in, because you should. I was always like, “Yeah, whatever,” because my head was so stuck in the artistry and the making of these things. I didn’t take that in and I should have.

Has the pandemic in a weird way been good for that? Many people have been forced to slow things down and get more reflective.

Oh yeah. It begins with just waking up and every morning [saying], “God. Thank you. Thank you. Another day of life.” That is exciting. Even the littlest things that we call the “little things” — like waking up, breathing, having fresh food to eat, having running water — are big things. I’m enjoying these luxuries and recognizing that they’re luxuries. For me, being here in the Bahamas in nature in a place that I have roots in and am able to isolate — but yet feel this energy from God and from nature and from the elements — [has] been very healing and I’m appreciative.

There’s always been a contradiction and duality in your life between the hedonistic rock star and the laid-back naturalist. You write in the book, “I am deeply two-sided.” Was that a natural outgrowth of who you are?

I’ve always had it, and it’s all I’ve known. I’m born a Gemini. My mother used to ask me, “Okay, which one of you am I dealing with today?” I’ve always thrived on it. I feed off the extremes. I can live on the street or I can live in a mansion. The middle, though, is not as appealing to me. I don’t get an energy from that that feeds me. At 15, my mother’s on the Number One [rated] television show. What do I decide to do? Leave because my father won’t let me go to a concert, and now I’m living in the street [or] people’s floors. I put myself in that position. I didn’t have to leave, but it worked for me somehow and it always has.

In 1995, you told us, “I want to do this till I’m old and little. I’d like to be like John Lee Hooker all in my little suit with my little gut hanging out, playing music, strumming my guitar.”

I don’t want the gut, but yeah, absolutely [I still feel that way]. When John Lee Hooker had that great success with that [1989] album The Healer, I was like, “Wow, okay, here’s an older guy and he’s having hit records and he’s touring.” Watching all the guys that I watched from Duke Ellington to B.B. King, who had to sit in a chair in his last performances. Mick Jagger is 70-whatever and can still rock a stadium better than most 20-year-olds. I’m in the middle now. I’m still young, and 20-some-odd years from now when I get to where Mick is, I’ll still be doing it if we have a world where we can do that. I plan on doing this until I can’t.

From Rolling Stone US