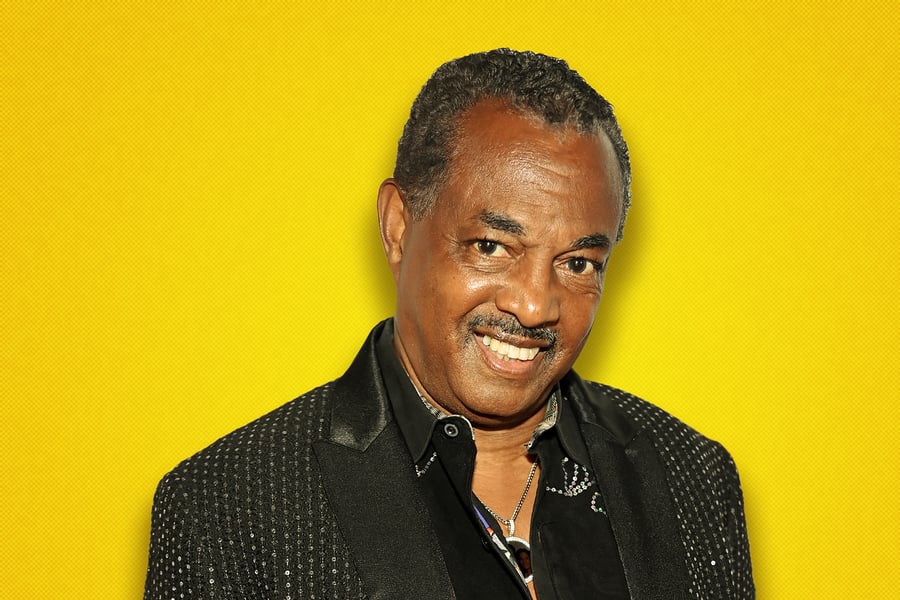

Kool & the Gang, one of the world’s greatest living groove-based bands, have been playing more than 100 shows a year for longer than Robert “Kool” Bell cares to remember. He was already adjusting to the unfamiliar sensation of a long stint at home in 2020 when tragedy struck — his brother and longtime bandmate Ronald Bell, known as Khalis Bayyan, died that September. Less than a year later, the group lost another co-founder in saxophone player Dennis Thomas.

“It’s not been easy,” Bell says. “We’re trying to keep moving forward. But my brother and Dennis are key members over the years.”

“Of course, in the last 20 years, we lost other key members,” Bell continues, ticking off names: Charles Smith, longtime guitarist, who died in 2006, Robert “Spike” Mickens, a trumpeter who left the band in 1984 and died in 2010, Larry Gittens, another trumpet player (2013), and Clifford Adams, a trombonist (2015). It’s the cruel reality facing a band that started back in 1964.

As original players fall away, the group keeps incorporating fresh faces. “Some of the new members have been with me now for 25 years,” Bell says, brightening. “New members can be old members too. You got to keep movin.’ Keep it movin’, and keep it groovin.’”

That’s as good an ethos as any for his group, which released Perfect Union, their 25th studio album, last year. “Hold On” is a slick ode to perseverance, with slippery guitar and pretty harmonies, while “High” channels the sound of early Seventies Latin rock groups like Malo — wrapping brassy runs around a brisk two-step — and “All to Myself” evokes the sugary danceability of mid-Nineties R&B. The album is shot through with square, uptempo beats and immaculately arranged horn sections, hallmarks of the Kool & the Gang sound since around 1979.

This band has had many iterations. After forming in the 1960s, the group — which had enough brass instruments to melt into a small statue — first started to earn hits in the early 1970s with funk based on the hard-driving templates of artists like James Brown. But where Brown’s music bristled like a clenched fist ready to let fly, Kool & the Gang’s was more of a cheerful wave; it was wild but also peaceful, making room for resplendently unhurried tracks like “Winter Sadness.” The band’s chanting, party-ready singles of this era — “Jungle Boogie,” “Higher Plane” — had much in common with the early hip-hop they preceded by half a decade.

But by the time rap began hitting the charts, Kool & the Gang had moved on, creating a tighter, lighter sound that was more repetitive and more danceable. They connected with the Brazilian writer-producer-arranger Eumir Deodato, whose rigorous approach and ideas about harmony and momentum were informed by his extensive time spent working with Antonio Carlos Jobim, Astrud Gilberto, Marcos Valle, and Milton Nascimento, among others. (Brazilian influences also added a jolt to another killer groove ensemble, Earth, Wind & Fire, in the 1970s; Deodato described their hit “The Way of the World” as “a samba with a cut-in-half drum beat to make it funk” in 2015.)

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

The late 1970s were an absurdly rich time for dance music: 1979 alone brought albums like Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall and Chaka Khan’s Masterjam, while Chic’s “I Want Your Love,” GQ’s “Disco Nights (Rock Freak),” Sister Sledge’s “He’s the Greatest Dancer,” and Stephanie Mills’ “What Cha Gonna Do With My Lovin’” all scaled the charts. Deodato helped Kool & the Gang streamline to compete in this ruthless environment. The band “used to come [in] with their songs that had about six or seven sections,” the producer said in a 2005 Red Bull Music Academy interview. “You can make ten songs out of this one!”

The new approach led to scrumptious 1979 hits like “Too Hot,” in which the horns are nearly silent and the rhythm section conjures beatific forward motion, yet Taylor stares resolutely backward, laying out the end of a high-school relationship in grisly detail. A commercially renewed Kool & the Gang enjoyed another eight years on the charts.

Kool & the Gang in the 1970s. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

It’s this period for which Kool & the Gang are most remembered. Sometimes even the hit parade from this era seems reduced to just two songs, “Celebration” and “Get Down on It,” which are the group’s most-streamed singles by a long shot. But Bell doesn’t seem to mind — he notes happily that “Celebration” was on President Biden’s victory playlist. He’s also counting on the track to help boost his recently launched line of bubbly, bottles of which sit next to platinum plaques behind him during a Zoom interview. “When people are drinking Cristal and Veuve Clicquot for new years, what song do they play?” Bell asks. “‘Celebration!’ So why not drink a little Kool champagne?”

The cheerfulness and ubiquity of those two tracks — along with a third, “Ladies Night” — has also helped Kool & the Gang land a fruitful side hustle opening for various rock bands of the same era. (Though one can’t help but wonder why the order of the lineup isn’t reversed.) “People are asking, ‘Kool and the Gang with these pop rock groups? How’s that happening?’” Bell says, pointing to recent stints supporting Van Halen as well as opening gigs for Elton John and Rod Stewart.

“David Lee Roth said, ‘listen, 60 percent of our fanbase are ladies and you guys wrote ‘Ladies Night,’” Bell recalls. “‘In the 1980s, we had ‘Jump’ and you wrote ‘Celebration.’ So, Kool, let’s go out and have a party.’” Van Halen fans weren’t immediately enthralled by the opening act, according to Bell. “We saw the Van Halen fans like, ‘come on, we want Van Halen.’ But when we got to ‘Ladies Night,’ ‘Get Down on it,’ and ‘Celebration,’ they jumped up and started partying.”

Maybe it’s not surprising, then, that much of the music on Perfect Union reaches for the sound of those hits, with crisp verses and brassy hooks. “‘Good Times’ — that’s almost like ‘Celebration,’” Bell says. His brother started composing the album before he died, and it’s dedicated to him. The songs are built on uplifting themes, and Bell repeatedly links the album to his hopes for “world peace” — a dream the band has endorsed at least since “Heaven at Once,” which came out in 1973.

From Rolling Stone US