One day in the late Nineties, Dave Lombardo, the metal drumming powerhouse best known for bringing a tornado-like fury to Slayer’s early thrash masterpieces, was driving from San Francisco to his home in Los Angeles. On the way, he threw on a recording of an unusual gig he’d just taken part in: a performance of a so-called game piece by John Zorn, in which the category-defying composer assembled a group of improvisers and staged a spontaneous sonic happening according to a series of rules, cards, and gestures.

For most of his musical life to that point, Lombardo had performed in highly controlled settings, but he’d always felt he had a gift for more off-the-cuff playing. With Zorn, he finally got the chance to explore it. And listening back to the show, he had an epiphany.

“I got a board tape of it, and while I was driving home from San Francisco to L.A., I felt this joy,” Lombardo explains, “’cause I felt that there were other musicians that thought along the same lines that I did when it came to music and being creative and improvisation and spontaneity. And I was happy, man. I was just like, ‘Wow, finally I found other musicians in another style of music that think like I do.’”

A few years earlier, Mike Patton had undergone a similar awakening. The Faith No More singer met Zorn when Patton’s other band, the genre-juggling art-metal outfit Mr. Bungle, invited the composer to produce their 1991 self-titled debut. Soon after, Patton and other members of the group started working with Zorn on his own projects, starting with Elegy, a 1992 album combining avant-garde chamber music and surreal soundscapes.

“He would give me direction in the studio, like, ‘Improvise this part,’” Patton recalls of his early Zorn sessions. “I’m like, ‘Improvise, what does that even mean? I’m a singer; I’ve got parts.’ He was just like, ‘No. No parts.’ So, really, he broke down musical language to me in its elemental particles.”

Speak to various Zorn collaborators about their experiences with him, and you’ll hear lots of stories like this: accounts of musicians engaging with unfamiliar styles and practices — and discovering facets of their creativity that they never knew existed.

Though Zorn has operated almost entirely outside the mainstream, he’s gradually asserted himself as one of the most influential musicians of our time. His projects and endeavors during the past 40-plus years could fill an encyclopedia: from rigorous classical works and radical reimaginations of Ennio Morricone film themes to deep explorations of his Jewish heritage under the Masada banner, whimsical neo-exotica, and sprawling improv excursions, where his sometimes jagged, sometimes supple saxophone playing mingles with the sound worlds of collaborators like Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson. But there’s one musical territory he’s mined again and again: the improbable intersection of jazz and the more extreme reaches of underground rock, from death metal to hardcore punk.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

These elements have swirled together in Zorn projects like the groundbreaking radio-dial-on-the-fritz ensemble Naked City, whose self-titled debut turns 30 this year; Painkiller and Bladerunner, improv collectives powered by elite metal drummers; and the aggro yet sensuous Mike Patton–fronted Moonchild. Though it represents only a fraction of his total creative activity, Zorn’s jazz-metal odyssey has forged new musical hybrids, fostered communication between scenes that once seemed entirely separate, and even inspired younger players to develop specialized skill sets that transcend any one style.

And the journey is ongoing. On June 26th, decades after Naked City’s seismic impact, Zorn, now 66, is releasing a brand-new style-smashing opus: Baphomet, the eighth album in five years by Simulacrum, a riotous death-metal organ trio teaming Medeski Martin and Wood organist John Medeski with members of vanguard heavy bands Cleric and Imperial Triumphant.

“The thing about John is, he’s asking a question,” explains Joey Baron, the renowned jazz drummer who’s anchored a slew of Zorn projects, including Naked City and Moonchild. “Like, ‘What would this be like with this?’ He’s asking that question, and then he envisions it. And then he hears it and he sees it, and he makes it happen.”

Summing up Zorn’s impact on himself and his peers, Patton simply says, “He made the world bigger.”

I. “The Joy of This Outrageous Juxtaposition”: From Spy vs Spy to Naked City

In early March, roughly a week before COVID-19 would bring New York to a standstill, John Zorn turns up at a Greek restaurant in his longtime East Village stomping grounds to discuss how his own musical world grew so vast.

Zorn’s omnivorous sonic appetite developed young. Growing up in Queens, he became fascinated with organ music after seeing The Phantom of the Opera, and later started playing flute and guitar. He learned Beatles songs, and caught a memorable Doors gig in 1967, paying special attention to Ray Manzarek on keys. But by age 14, he was already studying classical composition, and soon sought out more outlandish sounds.

“I was into modern classical — started with Bach and then moved to Ives and then, through movies like 2001, Ligeti, Kagel, Stockhausen, and it opened up,” Zorn says. “But a lot of that music at that time was very much a conceptual experiment. It was very intellectual. And it didn’t grab me on a gut level.”

Zorn found the immediacy he was looking for in jazz, particularly the work of progressives like Sun Ra, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and Cecil Taylor. He singles out a Taylor show he saw at a tiny SoHo restaurant in Manhattan in the early Seventies — when the late piano titan was giving the kind of marathon concerts documented on the 1973 live album Akisakila — as a turning point in his musical thinking.

“As soon as you walked in, the piano was right there and the drums, and then the place was packed,” he recalls. “And I came in and I was sitting under the piano — I mean, underneath the piano, on the floor, right next to everybody. And there was a cathartic experience. ‘Cause they started playing, and this is the Akisakila period, where Cecil was playing for two hours straight nonstop, full-tilt. I was coming out of [early-20th-century composer Anton] Webern, where every note had to have meaning. Every note, as a student composer, had to have a reason for being. And then I saw this, and it was a whole other world of power, emotional power, that it had. It was overwhelming. So I guess I spent the rest of my life — I’m still doing it — blending these two worlds of intensity and catharsis with very considered and well-thought-out formal plans.”

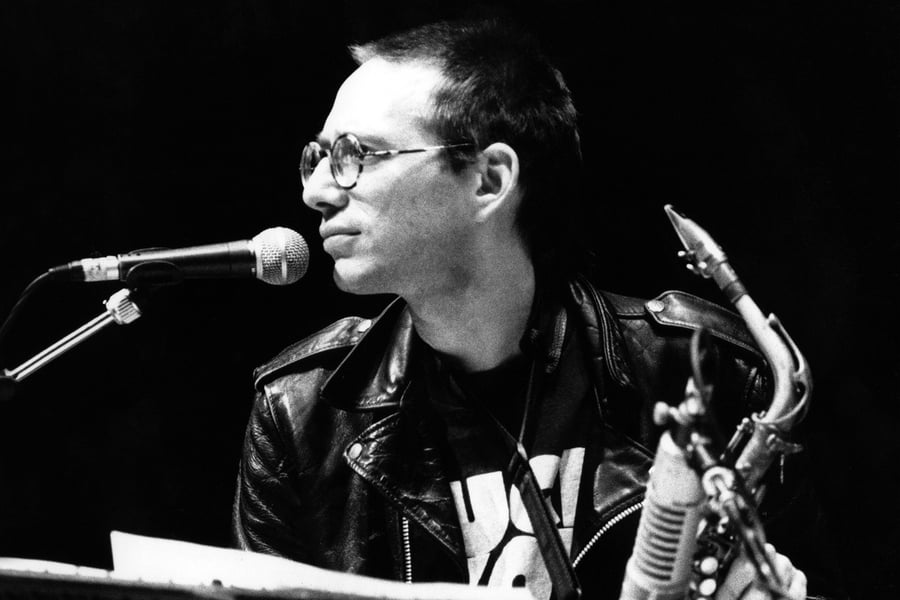

That duality once manifested in an image of a brash and brilliant rebel, restlessly traversing the Manhattan streets in his uniform of a leather jacket and camo pants, sometimes accented by a rattail haircut and a “Die Yuppie Scum” T-shirt. These days, Zorn retains the camo, but his bearing has softened somewhat; he now comes off more like a friendly uncle, happy to sit down and spin a few yarns about his wilder years, often chuckling at the madness of it all. But beneath his warm demeanor and old-school manners — even when talking, he insists that his tablemate’s plate stays full — Zorn remains vigilant. He’s exacting when discussing his work, and quick to wave off a question he feels is beside the point.

After high school, Zorn studied composition at Webster College in St. Louis. While there, he took up saxophone, inspired by For Alto, a landmark 1969 solo LP by sui generis Chicago composer-improviser Anthony Braxton. He also picked up on a key musical thread from his past, researching the work of Carl Stalling, who wrote music for the Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes cartoons Zorn loved as a child, and whom Zorn would later praise as “one of the most revolutionary visionaries in American music.”

Zorn dropped out of Webster after three semesters, and, following some time on the West Coast, made his way back to New York. By the mid-Seventies, he was giving conceptual performances at his downtown apartment, and assembling groups of improviser friends to take part in his early game pieces like Lacrosse, Hockey, and Pool. (“What I basically create is a small society, and everybody kind of finds their own position in that society,” Zorn once said of the intent behind these works, which include the celebrated, often-performed Cobra.)

In the Eighties, Zorn delved deep into jazz repertory, studying the work of bebop giant Charlie Parker, and learning tunes by lesser-known greats such as Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley, and Sonny Clark, the latter of whose work he covered on a 1986 album that also featured future Naked City bandmate Wayne Horvitz. Zorn signed with major-label subsidiary Nonesuch, which backed ambitious projects like his Morricone homage The Big Gundown and Spillane, a kind of aural film inspired by hard-boiled crime novelist Mickey Spillane. Meanwhile, a chance encounter outside East Village venue King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut sent him down another musical rabbit hole.

“There was some girl with dyed-blond hair and there was a group of people talking, and she says she’s the vocalist in a hardcore band,” Zorn recalls, noting that we’re currently sitting less than a block from where this took place. “I didn’t really know what that was, so, ‘OK, lemme see what that is.’”

Zorn didn’t have to go far to satisfy his curiosity. At the time, the center of the hardcore universe was just a few avenues west, at the Bowery club CBGB, where kids would flock to hear now-legendary bands like Agnostic Front and Cro-Mags play at epic all-ages matinee shows held on Saturdays and Sundays.

“You’d leave after seeing six bands completely drenched in sweat — I mean, as if you had dived into a pool of sweat,” Zorn recalls of the matinees. “I stood over by the wall, to stay out of the way. … It was pretty wild. And what I came away with was really more about intensity than musical content. A lot of the bands are just playing the same chords over and over, and the lyrics are usually — you know, you can’t understand most of them, except when everybody’s chanting.

“For the people in the room, it was very much a social, cultural experience; it was a place they could go to feel connected with people who were like them. For me, I wasn’t like them,” Zorn continues with a laugh. “I was older than them, you know? Like, ‘What’s this guy doing?’ I didn’t look like an old man, but I didn’t make any friends there. I wasn’t there for the hang; I wasn’t there for the scene. I was there to check the music out. And there were a few bands that I thought had really interesting musical content in terms of the form. Dealing with a limited amount of musical materials, you can still make something very, very interesting. … So I came away with that feeling of intensity, the kind of intensity that now we can connect up with seeing Pharoah Sanders, seeing Sun Ra, seeing the Art Ensemble.”

Spy vs Spy made that connection explicit. The 1989 release, Zorn’s third album for Nonesuch, consisted entirely of pieces by avant-jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman. Zorn, fellow saxist Tim Berne, bassist Mark Dresser, and dual drummers Joey Baron and Michael Vatcher played Coleman’s themes with absolute precision, but added a crucial twist: a crazed, cacophonous energy clearly informed by Zorn’s journey into the hardcore underground.

The album’s liner notes cataloged Zorn’s interests at the time. Included were shout-outs not only to Coleman, but also to CBGB and underground metal and punk outfits like England’s Napalm Death, Seattle’s the Accüsed, and Lip Cream, a chaotic group from Japan, where Zorn lived part time from the mid-Eighties through the mid-Nineties. The acknowledgments ended with an emphatic statement: “Fucking hardcore rules.”

“I’d been playing Ornette’s work since I first picked up the saxophone,” Zorn explains of the origins of Spy vs Spy. “I had a band with Tim where we did the stuff fairly straight, but when it came down to, like, ‘OK, this is not just at some party or in a basement somewhere, now we’re gonna go onstage and do it,’ it’s like, I’m not gonna do some half-assed version of Ornette with two saxes, bass, and drums, and just copy it. Does the world need that?

“Did you see that movie Listen to Me, Marlon?” he continues. “There’s all these tapes that Brando did talking to himself, and there’s one line where he says, ‘Do it the way it’s never been done before.’ And when I heard that, I was like, ‘Man, yeah, that’s the way I’ve been doing it all this time.’ I’m not gonna do Ornette the way [it’s been done] — it’s gotta be done like it’s never been done before.

“And [Spy vs Spy] certainly was never done before,” he adds with a mischievous laugh. “It also shocked the shit out of people.”

“I’m not gonna do some half-assed version of Ornette with two saxes, bass, and drums, and just copy it. Does the world need that?” —John Zorn

Zorn isn’t exaggerating. In the jazz community, the project touched a nerve. “Although intended as homage,” wrote critic Francis Davis in The Atlantic, recounting a performance by the Spy vs Spy band, “the concert amounted to heresy.”

Even now, Zorn clearly relishes the middle-finger jolt of Spy vs Spy and the work that would follow (he titled one Naked City piece “Jazz Snob: Eat Shit” and another “Perfume of a Critic’s Burning Flesh”). But he notes that his engagement with hardcore was also a straightforward reflection of his mindset at the time.

“Ramping the intensity up was one reason why I got attracted to that music,” he says. “Another reason was, on a very personal level, I was going through a lot of anger at the time, and you do what’s real. You don’t put it on like a suit of clothes; you do what’s real.”

That anger grew in part out of Zorn’s experiences in Japan, where he’d started to feel increasingly alienated.

“I found it really exciting at first, really stimulating,” he says of his life there. “I got accepted for who I was and what I was. But then the more I learned the language, the more I learned the culture, the more I understood how repressive it really is and why so many people want to leave there to be expressive, and how hard it is to survive. In some ways, that’s what drove me toward these more intense sounds.

“After a number of years, maybe 10, I began to feel, ‘Who am I?’” he continues. “Yeah, there was a lot of anger, and it was coming out in the music.”

Another thing that was coming out in Zorn’s music was a penchant for rapid-fire change. His college research had zeroed in on this trait, which he found both in Carl Stalling’s cartoon scores and the work of modern composers like Webern and Igor Stravinsky. “He would have a block of instruments working in a certain pattern and then … Boom! He would change to another,” Zorn once said of Stravinsky, singling out his 1913 landmark The Rite of Spring. “Throughout the whole piece that’s basically all that’s happening … Boom … Boom … Change … Change … Change, one thing to another.”

He later elaborated on this when discussing the ideas underlying the game piece Cobra:

“I think in blocks, in changing blocks of sound, and in that sense, one possible block is a genre of music: pop music, jazz music, classical music, blues music, hardcore music. They’re all blocks that can be ordered and reordered the way the 12 pitches in the chromatic scale can be ordered or reordered.”

If Spy vs Spy was about playing jazz with the ferocity of hardcore, Zorn’s next project, Naked City, focused on juxtaposing those styles and other “blocks of sound” in breathless succession. Everything was fair game: Slick funk, ambling country, chilled-out reggae, nimble bebop, stylish surf rock, moody klezmer, or assaultive bursts of noise-metal madness, punctuated by Zorn’s squalling alto sax and and the unhinged yowl of Yamatsuka Eya, vocalist of Japanese avant-punk wild cards the Boredoms. The result, heard in full flower on Naked City’s self-titled 1990 debut and 1992’s Grand Guignol, was a barrage of hyperactive, micro-detailed pieces that often exhausted themselves in less than a minute, leaving the listener dazed and exhilarated. (The band’s 1990 compilation album, Torture Garden, which landed on Rolling Stone’s 100 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time list, strung together 42 of these painstaking yet maniacal works, from “Thrash Jazz Assassin” to “Igneous Ejaculation” and “The Ways of Pain,” in under a half-hour.)

Naked City’s first album, from 1990. “I saw it as a compositional workshop,” says Zorn of the band. Cover photo by Weegee. (Photo: Nonesuch Records)

Rounded out by longer compositions like Grand Guignol’s dark, episodic title track, and covers of everything from pieces by Zorn’s modern-classical heroes to the James Bond theme song, Naked City’s early records were simultaneously a celebration of eclecticism and an assault on staid genre hierarchy. (“There’s good music and great music and phony music in every genre, and all the genres are the fucking same!” Zorn told an interviewer in the pre–Naked City days, and Rolling Stone’s original Naked City review later described the group as hopping among idioms with “the kind of grinning, methodical urgency you’d expect from a chain-saw murderer in a rush-hour subway car.”) The cherry on top was Zorn’s unsparing visual aesthetic: Naked City’s cover featured “Corpse With Revolver,” a grisly image by legendary New York street photographer Weegee, whose 1945 book — aimed at a tabloid audience who, Weegee once wrote, “had to have their daily blood bath and sex potion to go with their breakfast” — gave the band its name.

For Mike Patton and the other members of Mr. Bungle, a California band that had been mashing up funk, metal, ska, and more on their early demos, Naked City was an immediate revelation.

“I was with all the Mr. Bungle guys, and we were in a record store in Santa Rosa, California, and I found [Naked City], and it was in the jazz section, which for us was kind of like, ‘Eh, why go there?’” Patton recalls. “This was a long time ago, before my mind had opened. … And there it was, and on the cover was the famous Weegee photo, and I’m like, ‘I gotta have this,’ based on the cover alone. And I bought it, and I remember us listening to it on our drive to San Francisco, and we all freaked out. Like, we flipped out. And it was a moment. There’s a reason I remember that, because I think our worlds changed, especially for the Mr. Bungle guys. It was like, ‘This guy’s doing what we want to do!’ Or, ‘This guy’s doing something that we’re trying to do!’

“Listening to Naked City, to me, it just made every other band, every idea that we had had, sound lazy,” Patton adds. “Like, it sounded like it was on half-speed.”

“It answered everything we were hoping for from music, in a way,” says Mr. Bungle guitarist Trey Spruance of Naked City. “We were putting on Song X by Ornette Coleman and then listening to Slayer and then putting on Stravinsky; that to us is like the collage that we sort of envisioned in a way, coming together in one piece. And we weren’t really sure how to do it; we were sort of ambling our way towards that kind of a thing. And all of a sudden, the first Naked City was out there. … It seemed to us that this was just a natural place that music was going, and [John] was out there in front of it.”

It makes sense that Naked City registered as a new benchmark for musicians looking to break out of genre confines, since for Zorn himself, the band was all about testing both his own limits and those of his bandmates.

“I saw it as a compositional workshop,” he says of the group, whose core lineup also featured Spy vs Spy’s Joey Baron on drums, along with Wayne Horvitz on keys, guitarist Bill Frisell, and bassist Fred Frith. “Let me pick the five best musicians I know, who can play everything, and see what I can do with those guys and how I can challenge them.”

Given the band’s capability for feral intensity, it’s almost miraculous that the players involved were largely unfamiliar with the thriving hardcore and metal underground that Zorn was exploring at the time. Naked City drummer Baron started out as an actual self-described “jazz snob”; his early CV included work with heavyweights of the genre like singer Carmen McRae and guitarist Jim Hall. In the early Eighties, after moving from L.A. to New York, he started playing with cutting-edge bandleaders like Tim Berne and Bill Frisell. He met Zorn in 1987, when both were a part of Ambitious Lovers, a skewed pop outfit co-led by No Wave guitar luminary Arto Lindsay. Baron remembers covering bands like Cream and Vanilla Fudge growing up, and says he saw a gig by the punk band Fear when he was living in L.A. But before his time with Zorn, he’d never played anything remotely resembling a blast beat — the jackhammer rhythm pioneered in the mid-Eighties by drummers like Napalm Death’s Mick Harris, and a key element of the Naked City sound.

“He had tapes of stuff like Napalm Death,” Baron explains of how Zorn illustrated what he was looking for. “He would play it for me, and I was not into that scene at all. … But John had a definitely formed picture, and he could clearly define it by what he chose as examples to play for me, and that really helped me focus in and kind of go for the essence of what he was looking for.

“And I’m not a hardcore [drummer]; I wouldn’t categorize myself as that,” Baron continues. “But I just tried to go for the essence, rather than a robot copy of something. And I tried to just keep whatever I bring to the table and just add a sensibility that John was looking for. But John, I think he did illustrate that, and he would occasionally just tell people, ‘No, I want noise. Just scratch those notes out, unplug the cord on the guitar …’ He was very direct, very precise. He knows exactly what he wants, and he’s usually pretty good at describing it if what he wants is not happening.”

Bandmate Bill Frisell was also a hardcore neophyte. Now one of the world’s most celebrated improvisers, the guitarist was just starting to make headway on the New York jazz scene when he entered Zorn’s orbit in the early Eighties. He met Zorn at the SoHo record store where the composer worked, and went to hear one of his early game pieces. (“It was like I’d just landed on another planet,” Frisell recalls of the gig.) Shortly after, he participated in one himself, meeting future Naked City colleagues Horvitz and Frith through the experience. By the mid-Eighties, Frisell and Zorn were constant collaborators. The guitarist appeared on early Zorn records like The Big Gundown and Spillane, and even performed with him in Japan.

Zorn gave the guitarist his own hardcore crash course. “I remember when I was in Japan, he played me some Japanese hardcore band, with, like, a Sony Walkman,” Frisell says. “He put the headphones on [me], and I listened to this thing, and it was like hearing Stravinksy for the first time. It blew my mind. It just opened my senses to the possibilities there.”

“[John] played me some Japanese hardcore band, with, like, a Sony Walkman. … It was like hearing Stravinksy for the first time.” —Bill Frisell

Beyond just getting acclimated to Zorn’s hardcore-informed aesthetic, the players had to condition themselves to withstand the force of the music itself — especially when performing in small clubs like SoHo’s Knitting Factory.

“I’d never really played that loud,” Frisell says. “Wayne and Joey and me, we all got these custom-made earplugs, just to be able to deal with it. I think Fred and John were cool with just being in it. But it was brutal. … I remember some of the times at the Knitting Factory, what it felt like on the stage — I just had to have those earplugs in. It’s like you’re in the middle of this storm. It was physical; you could feel it in your body.”

“That’s the hardest physical work I’ve ever done,” says Baron of playing in Naked City, and adds that, at the time, he took lessons in endurance from famed Dave Brubeck drummer Joe Morello to help him manage. One particular chapter of Naked City nearly pushed him to the brink: when the band was performing its 1992 release Leng Tch’e (the title refers to the Chinese execution method known as “death by a thousand cuts”). Here, the group traded “blocks of sound” jump-cuts for an excruciatingly slow half-hour doom-metal hellscape punctuated by manic drum eruptions.

Looking for the next frontier in heavy at the time, Zorn says he turned his attention from speed-crazed grindcore to the lumbering churn of bands like the Melvins. “OK, I’ve mastered the Webern, 30-second, one-minute piece that’s not just one scream, but that actually has a structure, has a form, and there’s maybe 10 or 20 different elements in that short 30 seconds,” Zorn says. “What can I do with a long-form piece of that intensity? As a composer, it’s the natural thing, to challenge yourself every which way you can. And the inspiration in that world was the Melvins. I thought they were amazing.”

“I’ll never forget,” Baron says with a laugh when asked about performing Leng Tch’e. “It’s extremely exhausting for the drums. Because, you know, the electronic instruments, they can just turn up a knob and the sound is there. To compete with that or to blend with that [as a drummer], it’s not just the PA being loud; you’ve got to hit like that. That was extremely challenging for me, because it’s a long time: If you’re doing a blast beat, 30 seconds can seem like hours.”

Yamatsuka Eye entered Naked City a bit better prepared. The vocalist, who’s around 10 years Zorn’s junior, was accustomed to wildly over-the-top performance styles; as a member of the Osaka, Japan, noise band Hanatarash, he’d shriek with alarming fury, abuse power tools onstage, and leave venues literally leveled.

Eye knew Zorn’s work well when he met the composer in Japan in the late Eighties at a show by Geva Geva, the vocalist’s trio with fellow rock extremists K.K. Null and Tatsuya Yoshida (both also later Zorn collaborators).

“John Zorn’s music and jam sessions were already on heavy rotation on my Walkman back then,” Eye (now known as Yamataka Eye) writes in an email. “His music really expanded my consciousness and influenced me, so I was really happy when he came up and talked to me.” He recalls hearing various Zorn solo albums, as well as improv collaborations with Arto Lindsay and experimental guitarist Elliott Sharp, on tapes he’d gotten from friends. “It was refreshing to hear this new approach to improvisation, and listening to him felt like juice was being squeezed from my brain,” Eye says.

Zorn invited Eye to perform with Naked City, and his debut with the band came at a 1989-90 New Year’s Eve show at New York’s Puck Building. Within the band’s highly structured sound world, Eye acted as a carefully deployed chaos element, cued in and out by Zorn. “John’s hand signals either meant ‘stop’ or ‘go,’ and besides that I was free to do what I wanted,” Eye says. “My approach was to insert my voice as a dynamic object into the performance,” he adds.

As for the band’s signature jump-cuts, he wasn’t fazed in the slightest. His band Boredoms would soon become well-known in the West for their ecstatic, off-the-wall approach to rock, so he felt right at home within Naked City’s rapid-fire shifts.

“During the performance, there would be moments that sounded like a scene from a film, but the next bar would transform into something completely different,” he recalls of the Puck Building show. “While we were performing, it didn’t feel like we were destroying the context of the music, but felt more like a three-dimensional and multifaceted sensation of riding a vehicle, which felt really good. My brain would automatically integrate all these sounds together into one image. This approach felt more real to me than the music I had listened to up until then, and was close to the way I perceived music in reality. I wouldn’t call this music ‘eclectic’; it was more like the way we perceive dreams. It was like a holistic and balanced presentation of reality to me.”

Eye soon became an integral part of the band. Frisell recalls being awed by the vocalist’s intensity as a performer, and struck by his unusual way of preparing for shows.

“It seemed like he was sleeping all the time,” Frisell says. “He would just sleep, and then he would wake up and he would go nuts. … It was so wild. It was like he would hibernate, and then when it was time for the gig, this force was unleashed.”

Eye confirms that hibernating was more or less exactly what he was doing.

“In order to put all my energy into the live shows, I was pretty much sleeping when we weren’t onstage,” he says. “I would sleep on the side of the stage until the moment John would call me for my vocal parts. … After awaking from my sleep, I would scream as hard as I could, with my body convulsing as if I was having an epileptic seizure. When I did this, it felt like my consciousness was being cracked open, and I started to think that there was something to this, so I also started to believe that there may be some kind of correlation between screaming and sleeping.”

“Listening to [John] felt like juice was being squeezed from my brain.” —Yamataka Eye

Eye says he wishes he could have gotten to know the other members of the band aside from Zorn better, but that the language barrier made it tough. Musically, though, he felt totally aligned with them, despite the fact that they came from very different backgrounds. To him, Naked City’s marriage of jazz spontaneity and hardcore power only confirmed what he’d seen around him in the Japanese underground.

“I personally never thought that jazz improvisation and hardcore punk were utterly different worlds,” he says. “For example, [Dutch free-jazz drummer] Han Bennink heavily influenced a lot of Japanese hardcore drummers. John may have also sensed the similarities between these two worlds, but I think that he was the only person back then to interpret the explosiveness of extreme metal and grindcore as a form of jazz and present it in a new way.”

Even as the band pushed them past their physical limits, Frisell and Baron stress that playing in Naked City was often pure joy. When asked about performing with Eye and the band’s later-period vocal guest Mike Patton, for example, Baron lights up.

“It was capital F-U-N,” Baron says. “I’d never heard anybody do what either of those guys did. … Even though [Eye] spoke no English, it didn’t matter. We were a team. And same with Patton. He’s really talented; he’s an amazing, flexible, versatile vocalist. Unbelievable. And very funny also.

“It was just a ball doing things together,” the drummer continues. “And when we were in the heat of the storm or the heat of the battle, just all of us giving our 110 percent to help bring about John’s vision of the music, it was just fun and exhilarating.”

Live videos of the group back up Baron’s account: As fearsome as Naked City could sound, smiles and laughter were omnipresent onstage. Zorn says that mood might have led to his intentions for the project being misread.

“A thing that was really misunderstood at the time was, people thought this was some kind of ironic joke, ’cause postmodernism was really big in the Eighties,” he says. “So, when we were laughing, having a great time, everyone thought we were laughing ’cause it was ridiculous, or something, that we were laughing at the music. You can ask anybody I ever worked with: I never did anything that I didn’t believe in 1,000 percent. It’s sincerity, always.

“Why we were laughing was just sheer joy: the joy of music-making, the joy of this outrageous juxtaposition,” Zorn continues. “And when you laugh, you’re not always laughing at something. But see, the audience couldn’t swing with it. They couldn’t understand. ‘How could someone like that enjoy so much music? There must be something else going on.’ Maybe they were laughing at it, so then they put it on us. We never laughed at anything we did; we loved it, and we had a great time doing it, and that’s where the laughter came in.”

“I’ve had the experience where someone thinks I’m joking or making fun of something, and I just don’t do that, and that’s not what we were doing,” says Frisell, who has gone on to cover everything from the Beach Boys’ “Surfer Girl” to the Happy Trails theme song in his own later work. “And I know that’s [John]: Everything he was putting in front of us was out of love of the music, like total respect of the music.”

The love that Zorn put into the group, and his commitment to always finding somewhere new for it to go — as on Naked City’s fascinating final statement, 1993’s Absinthe, which traded jazz, metal, and pretty much every other recognizable genre for pure textural oddity — brought about a deep commitment on the part of the other members. According to Baron, what made projects like Naked City and Spy vs Spy work wasn’t about whether he and the other players in the group came from a metal or hardcore background, but that they approached the project with open minds and a real dedication to realizing Zorn’s wildest musical fantasies.

“The audience couldn’t swing with [Naked City]. They couldn’t understand. ‘How could someone like that enjoy so much music?’” —John Zorn

“John always has a vision, a very clear vision; he’s incredible that way,” Baron says. “And I think his vision is a lot of times something a lot of the participants don’t really know about or they don’t have, but that’s where the trust comes in and the respect; all that comes into play, and that kind of lays down how it will come out. The thing that made it work was, I think, that everybody involved trusted, and nobody judged it.”

That trust ultimately made Naked City a school unto itself. In Zorn’s eyes, their unconventional approach to hardcore — for example, the way Baron played blast beats using a jazz drummer’s traditional grip, with the snare-hand stick held sideways, rather than the “matched” grip favored in rock and metal — was a plus: the result of musicians being pushed outside their comfort zone and finding a novel way of addressing the challenge.

“At that particular point in time, there were just a handful of people that could’ve covered that range and make it real on the planet,” Zorn says. “Now it’s commonplace, but back then it was cutting-edge that anyone could do that amount of different musics authentically, and make it their own. Whenever Frisell does anything, he makes it his own. And Joey too. And I did talk to him about playing with matched grip. I said, ‘Look, I’ve been going to these [hardcore] gigs; they’re all playing matched grip; you can get a little faster with it.’ He’s like, ‘John, this is the way I play; don’t tell me how to play.’ ‘OK,’ I take two steps back. …

“It’s like a learning moment. You don’t tell someone how to do something; you give them a problem and have them solve it. So from then on, I was just like, ‘Great.’ And what made that music so unique was the fact that they weren’t [hardcore musicians], they weren’t playing clichés, ’cause they were unique.”

Part II: ‘Hidden Passageways’: Painkiller, Bladerunner, and Beyond

At the same time that he was exposing jazz-oriented players to hardcore in Naked City, Zorn was also experimenting with the opposite approach in a series of groundbreaking improv groups. One of the first to enter Zorn’s world through this channel was drummer Ted Epstein.

Epstein had never heard of John Zorn when he moved from St. Louis to New York in the fall of 1986 along with his bandmates in Blind Idiot God, an instrumental trio that alternated between brawny, structurally intricate hardcore and cavernous dub reggae. Not long after, Zorn caught the band live at CBGB, liked what he heard, and asked them to fly overseas for a collaborative gig.

“From the time I first heard of John Zorn to the time I was playing on a stage in Italy with John was maybe two weeks,” Epstein recalls.

Zorn worked with the entirety of Blind Idiot God, teaming with them on a Naked City–style original called “Purged Specimen,” as well as early versions of a couple of pieces that Naked City itself would later tackle. But soon he began calling on Epstein for other opportunities, recruiting him for an explosive cover of the Stooges’ “T.V. Eye” that also featured Eye on vocals, and once even asking him to sub at a Spy vs Spy show, where he played alongside Baron.

“He seemed to really enjoy what would happen when he just threw me in crazy situations,” Epstein says. “I didn’t know Ornette Coleman songs. I might have tried to listen to some on my Walkman on the way there or something, but, no, I didn’t know the music. … It just kind of happened, and it was really great, honestly.”

Soon after, Zorn and Epstein came together in a new group with Elliott Sharp. Calling themselves Slan, the trio — once dubbed by Zorn as “the world’s first all-Jewish heavy-metal band” — played New York and toured Europe and Japan in 1990. Their sound was a free-form noise-jazz pileup that fully embraced Epstein’s pummeling, metallic style.

For the drummer, who had never improvised before working with Zorn, holding his own with players from that world was instructive and inspiring.

“He led me to realize that I could do things that I didn’t know that I could do,” Epstein says of Zorn. “Or that I could adapt musically to situations that I might have considered just beyond me. And definitely part of that, honestly, was just realizing that whatever instincts I had musically, whatever techniques I had under my belt — even though I thought of them as being really rock or funk or hardcore or punk, or whatever I thought they were — they really weren’t exclusive to any particular genre, that jazz is big enough that you can do lots of things within that, under that umbrella. And there are connections there that you don’t see.

“There are these hidden passageways between different genres of music,” he continues, “and especially when you have the privilege of working with really great musicians, you get to see how you can travel along those different axes, and find your way to something.”

At the time, Zorn was traversing these passageways constantly, guesting in the studio with industrial-metal weirdos OLD and playing live with the Rollins Band rhythm section of bassist Andrew Weiss and drummer Sim Cain. For his next sustained genre-spanning improv venture, Zorn delved even further into the rock underground to recruit a player he’d already drawn considerable inspiration from (and played for Baron to acclimate him to the way of the blast beat): Napalm Death drummer Mick Harris.

Zorn had been a fan of Napalm Death for a few years, ever since a clerk at an East Village record store had turned him on to them. (“I just said to the guy, ‘Pull out five of your favorite hardcore records, just things that have been on your fuckin’ turntable nonstop,’” Zorn recalls, “and one of the ones he pulled out was Napalm.”) Influenced by the more extreme end of American hardcore, the British outfit upped the speed and aggression to unprecedented levels, compressing their songs into brief, white-knuckle tantrums — including one that famously clocked in at barely more than a single second — on future cornerstones like 1987’s Scum and 1988’s From Enslavement to Obliteration. Zorn got in contact with the band’s label, pioneering U.K. grindcore imprint Earache, and in the summer of 1989, during one of his stays in Japan, he caught up with Napalm Death backstage at a Tokyo show. Mick Harris was already a Zorn fan, having been turned on to Spy vs Spy by Earache employee Martin Nesbitt, and the two chatted about a possible collaboration.

From there, they stayed in touch. “I used to send John Zorn postcards when I was on tour with Napalm,” Harris recalls. “Say I was in Germany, or wherever I was, I would always send John Zorn a postcard. I would send [renowned BBC DJ] John Peel a postcard, I’d send my mom and dad a postcard, and I’d send my wife, Helen, who was my girlfriend back then, [a postcard] — so it was always four postcards that went out.”

Harris visited New York in early 1991. He met up with Zorn for some food and record shopping, and the two continued their chat about working together. They’d made no specific plans prior to Harris’ visit, but on the spot, Zorn suggested they do some recording. Harris mentioned he was a fan of Last Exit, a brash, punishingly loud improv group convened in the mid-Eighties by hyper-eclectic bassist-producer Bill Laswell. Zorn and Laswell were friends who had run in the same downtown avant-garde circles for years, and — during joint and separate trips overseas — had bonded over a shared interest in the wildest Japanese hardcore records they could find. So Zorn called up the bassist the very same night, and he booked a session for the trio at Laswell’s studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

On the day of the recording, Harris, who had never improvised in his life, found himself in a cab with Zorn on the way to the studio to make an entirely improvised album with two world-renowned practitioners of the style.

“So you can imagine — just a little kid I was,” Harris says. “I’ve never been in that situation before. Yes, I’d met John, obviously, but I’ve never met Bill, never improvised like that in the studio before. I was a two-bit, self-taught punk drummer, and confident of what I did with Napalm, but outside of that, I don’t know.”

Arriving at the studio, Harris marveled at Laswell’s master tapes, evidence of his production work with everyone from Mick Jagger to Motörhead. He picked out a drum kit, and then the band got down to business.

“John’s like, ‘Yeah, Mick, Bill’ and ‘Bill, Mick.’ And, ‘Yeah, let’s just put the cans on, let’s run the tape and do it.’ ‘Well, do what?!’” Harris recalls, cracking up at the memory. “[John] said, ‘Don’t worry, it’ll be fine. Just get behind the kit and do what you do.’ That was it. Three hours later, we’d done this record.”

The results became an underground landmark. Released in late 1991 on Earache as Guts of a Virgin — and credited to Painkiller, a moniker that both Zorn and Harris confirm wasn’t a reference to the 1990 Judas Priest record of the same name — the EP was an organic, on-equal-footing meet-up of jazz and rock’s furthest extremes, with Zorn’s alto sax screeching over Harris’ frantic blasts and the massive rumble of Laswell’s bass.

The album’s gruesome cover art, showing an autopsy of a pregnant woman in graphic detail, resulted in a police raid on Earache’s U.K. office, after the photos were seized by customs en route to the label. “This was before the internet; I don’t know where he’d get these photos from,” says Digby Pearson, the label’s founder. “Anyway, it was pretty shocking and pretty horrible, and then I spent six months fighting a criminal case which didn’t eventually go to court, because my lawyers had to spend a lot of time to save me going to prison over this.”

Full-bore shrieking from both Harris and Zorn only heightened Painkiller’s unapologetic rawness. “My family yelled and screamed my entire childhood; that was what they did,” Zorn says when asked about his affinity for such extreme vocals, which he also provided at times in Naked City and Slan. “That’s how they communicated with other. Screaming was very natural for me; it’s in my blood.”

Occasionally Zorn and Harris got assistance onstage from guest screamers that included Yamatsuka Eye.

“Painkiller was like a pair of extremely tense wire ropes that are crisscrossed,” Eye says. “The wires are pulled so tightly that they might split at any moment, but when you pluck them, they produce an incredible sonic vibration. The point of intersection of these wire ropes is a safety zone where you can escape the effects of gravity, and you can even place a tray with cookies or teacups. The tension is so extreme that a zone of relaxation is produced automatically. I was able to insert my screaming into that zone, all thanks to Zorn.”

Painkiller would move far beyond its primitive origins. The band went on to explore ominous long-form moodcraft — enhanced by live engineer Oz Fritz — on later albums like Execution Ground. “Mick would go from these blast beats, these really short, fast, extremely intense patterns, and then the next thing might be almost like a dub, atmospheric kind of thing, where he’s playing very minimal and incorporating dub into it without any connection to reggae,” recalls Laswell.

“Screaming was very natural for me; it’s in my blood.” —John Zorn

After a healthy amount of gigs, which took them from New York’s Knitting Factory to Japanese clubs and European jazz fests, the trio’s original lineup dissolved around the end of the Nineties. Harris plunged into the electronic-music underground with projects like Scorn; meanwhile, Zorn and Laswell would continue Painkiller with various other drummers, and would reunite with Harris for a single gig in 2008. (Zorn would go on to lend electric-shock sax solos to a 2012 track by the current incarnation of Napalm Death, which doesn’t include Harris.)

Looking back, Laswell sees Painkiller as a polarizing but ultimately galvanizing force within the larger world of jazz and improvisation. “It helped connect a lot of things to a lot of people, and I don’t think it necessarily inspired the fusion-jazz people,” Laswell says. “I think it was very confusing for those people, or concerning, or maybe disappointing. You know, you play Painkiller at a jazz festival in Europe somewhere and the opening act might be anything from Betty Carter to some smooth-jazz thing, and when you play this sound with Painkiller, which live is pretty loud, you get this effect of half the audience runs off, the jazz people, and then half the audience comes forward, and those are usually the kids, and the people that come for something else — not for the jazz. And by doing that, by showing that division, it changes festivals, so all of a sudden they start to book more interesting things. … It kind of sets a new standard.”

For Zorn, Painkiller was a chance to commune directly with the kind of raw, punk-minded aggression he’d originally savored at CBGB. “The guy was a maniac; the guy was amazing,” Zorn says of Mick Harris. “One of the most original drummers ever in the history of the world. It was incredible. He may not have been a schooled drummer … but he did his thing, and it was so intense — and he meant it with 1,000 percent of his being. He’s not someone that would ever phone anything in. Not one note was insincere.”

For Harris, the project was an assurance that he had something to offer the world beyond his role in Napalm Death, a band he left the same year Painkiller started. “With Napalm, there was a style, and in the end it’s something that I really hated and the reason that I moved away,” Harris says. “I felt sort of trapped in a box, that it was just ‘duh-duh-duh’ and nothing else. I was lucky getting the opportunity to work with John and Bill, ’cause they opened doors, opened possibilities, and just gave me that chance.

“John knew how much I had a real self-hate for my drumming, that I felt I was trapped in something,” he continues. “But he said, ‘You’ve got to embrace it, Mick. You have something there.’ And I said, ‘I do know I’ve got something, John, but I’ve got one bow.’ He said, ‘No, you’ve got more than that.’ … This is where John, he gave me something. That is true friendship and true words. He just said, ‘Mick, you have a fire. There’s people out there that are technical as anything. You’re not technical, Mick; that’s not your thing.’ He said, ‘But these technical people, they haven’t got a fire; they haven’t got a soul.’”

Beyond Painkiller, Zorn’s alliances in the grindcore world had a broader impact. Earache’s Digby Pearson — who, prior to putting out Painkiller, had released albums by Zorn favorites like Carcass and the Accüsed, along with Napalm Death — remembers being bewildered by Zorn at first, when Harris and Martin Nesbitt started singing the composer’s praises.

“I never actually signed the guy, or even wanted to work with him,” Pearson recalls with a laugh. “He kind of wormed his way in.” But on the strength of his colleagues’ recommendations, Earache licensed Naked City’s Torture Garden for a U.K. vinyl release in 1991.

“My problem is, I’m a bit of a philistine,” Pearson says. “I don’t mind admitting it. I’m just meat-and-potatoes hardcore punk, thrash, grind, and I was on a mission to just do that. And [Zorn’s] avant-garde leanings and all that were not my cup of tea.”

But eventually Pearson grew to appreciate Naked City’s outré charms. “When I finally heard it, I got it; I’m like, ‘OK, this is amazing. It’s like 40 tracks in, like, 20 minutes or something,’” Pearson says of Torture Garden. “When you listen back to it now, it’s 30 years ago and it’s so contemporary. … It’s almost pre-told the whole idea of Instagram or Vines or whatever, or six-second attention spans.”

Pearson also credits Zorn with helping to lend Earache and the developing grindcore scene an air of legitimacy.

“The bands and the musicians I was dealing with were literally from council estates, really young, 18, 20, doing their first albums in this industry, as I was — very much hardcore punk, kind of DIY-label vibe,” he says. “[Zorn] was the first guy, really, that had some clout, who gave everything a kind of respectability, which was very much appreciated. … ‘Cause it was such unlistenable music, it never occurred to me that Napalm Death was avant-garde, and he made that connection, John Zorn, and wanted to jump into it, which was great.”

The association between Zorn and Earache was brief, spanning just the Torture Garden reissue and Painkiller’s Guts of a Virgin in 1991 and another Painkiller EP, Buried Secrets — which featured appearances from members of U.K. industrial-metal juggernaut Godflesh — in 1992. But the connection would have a lasting impact for the label.

“There are actually loads of fans of Earache now that came on board at that period because of John Zorn, and stuck with me and went on to follow the journey since then, because he was an established artist,” Pearson says. “Looking back in hindsight, it was a perfect little collision between the worlds of avant-garde that he was involved in and the purist, if you like, grindcore that I was trying to develop.”

Back in New York, Kevin Sharp, a vocalist whose intimidating roar played a central role in the New York grindcore band Brutal Truth, had become a Zorn secret weapon of sorts. At various times, he joined Naked City onstage (sharing vocal duties with Eye), guested with Painkiller, and participated in an all-vocal edition of Cobra.

“John, he was like the essential educated musician; he was like the John Peel of America,” Sharp says. “He knew all music.”

“John was like the essential educated musician; he was like the John Peel of America.” —Kevin Sharp

Sharp credits Zorn with turning him on to revelatory albums by Captain Beefheart and Funkadelic, but more important, with pointing the way toward a broader musical aesthetic. Brutal Truth’s first LP, 1992’s Extreme Conditions Demand Extreme Responses, was an intense but straightforward grindcore record, like a more refined version of what their U.K. predecessors had churned out in the late Eighties. But on their second record, 1994’s Need to Control, the band came gloriously unglued, embracing a more chaotic and experimental sound that included noise interludes, more varied tempos, and even some guest didgeridoo, played by Andy Haas, a musician whom Sharp recalls meeting through Zorn’s orbit. From that point on, the band — and Sharp, in various other projects — would fly its freak flag with pride.

“His insanely expansive taste in music just forced everyone to up the game, so to speak,” Sharp says of Zorn. “We could have easily done our first record subsequently 10 times over. … I would say he encouraged me to really diversify instrumentation sounds, and also he taught me to follow the love of music and try not to focus on the business. And I kind of made a life out of that, so, hey, thanks, dude. It was a huge impact on me.”

Dave Lombardo would also see his world expand considerably after meeting Zorn. In the Eighties, the Cuban-born Lombardo redefined heavy-metal drumming with his double-kick–driven barrage on Slayer albums like Reign in Blood. He left the band in 1992, after recording two more all-time classics, and formed new project Grip Inc. In 1998, he met Mike Patton at one of the singer’s final shows with Faith No More, before their initial breakup. Patton recruited Lombardo for his new band Fantômas, and shortly after, on a hunch, the singer introduced the drummer to his friend John Zorn.

“I remember telling John, you’ve got to play with this guy Dave Lombardo,” Patton recalls. “I had started working with him in Fantômas, and I mean, he’s kicking the entire band’s ass. He’s, like, that good. And I told John, ‘Man, you’ve got to work with this guy. You’ve got to bring him out of his shell.’”

That process didn’t take long. Lombardo’s first encounter with Zorn came in September 1998, when, during an eventful two-day stint at the club Slim’s in San Francisco, the drummer played with Zorn twice, first, in a spontaneous sax-drums-vocals trio with Patton, and second, as part of a seven-piece band, also including Mr. Bungle’s Trey Spruance, performing the Zorn game piece Xu Feng.

“We performed onstage and created this barrage of noise, yet it was controlled and conducted,” Lombardo recalls of the Xu Feng experience. “It was enlightening for me to be a part of these musicians; it was just so much information. I was a sponge; I was loving every moment of it, because it had to do with improvisation.

“And I felt from my experience prior to meeting Patton that I had this — I don’t know whether you want to call it a gift or a talent, or whatever it is, where if someone starts something, a rhythm, a melody, a pattern, I could pick it up from where they left off and just continue improvising off of that. So listening was a big part of improvisation in those kinds of performances, and that was something that I was able to do.”

“[John’s] got this weird quality; I would call it a Cupid-like quality. He brings people together.” —Mike Patton

The Zorn-Lombardo collaboration progressed, and eventually the two formed a band: a quartet calling itself Bladerunner, which performed sporadically in the late Nineties and early 2000s, and also appeared on one track of Zorn’s 1999 album Taboo and Exile. Much as he had done with Mick Harris in Painkiller, Zorn gave Lombardo a chance to play with Laswell, a musician the drummer greatly admired. Naked City bassist Fred Frith — a veteran improviser who had also played in the British avant-garde rock band Henry Cow and previously worked with Laswell in early-Eighties prog-punk outfit Massacre — rounded out the group on guitar.

“He’s got this weird quality; I would call it a Cupid-like quality,” Patton says of Zorn. “He brings people together. And I don’t know how he does it. I don’t have that gift. There’s a certain energy that makes that happen. And being able to speak different musical languages is a big part of it, and he’s really, really adept at that.”

“[John] had found out through Patton that one of my favorite bands in the late Nineties was Last Exit, with Bill Laswell,” Lombardo recalls. “I loved that band. So when he found out that I was into Laswell, he said, ‘Oh, Laswell’s my friend. C’mon let’s do shows.’ And it blew me away. I was like, ‘What? I get to play with Laswell?!‘”

As with Painkiller, the band’s sets were all improvised and allowed the drummer to show off the full range of his abilities, from the speed-metal onslaught he’d perfected in Slayer to crisp funky beats and sparse accents that complemented the rest of the band’s jazzier, dubbier excursions.

Recalling the enthusiastic reception the band received at jazz festivals in New York and Paris, and at London’s Barbican Center, Lombardo sounds fired up, like the thrill hasn’t worn off 20 years later.

“Just these incredible moments that we shared onstage — Zorn pointing at me: ‘A little more of that …’ — just conducting and listening,” Lombardo says. “And it was all improvised! We would go onstage, play about 40 minutes, and people would think it was all written, but it wasn’t. It was so well-executed that people didn’t know we were performing this improvisation.”

Bladerunner paused in the early 2000s when Lombardo returned to Slayer, but resumed in 2014 after the drummer had parted ways with the metal band for good. In 2015, as part of a daylong Zorn marathon in L.A., Zorn and Lombardo performed both with Bladerunner and as a duo, situated in front of a Jackson Pollock painting at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“The duet in the Pollock exhibition was unreal,” Lombardo says. “Just Lombardo on drums, Zorn on saxophone. It’s insane what happens. So instinctual, so primitive, all relying on just listening to each other and where each other in that split second is going to go musically.”

“Performing with Zorn for me is liberating; it’s freedom,” he continues. “There’s absolutely nothing holding you back. No format, nobody telling you where to go musically, or anything. It’s just so refreshing, and I can go back to my regular music that I perform live in a different genre, and I’ll feel refreshed; I’ll feel cleansed almost. It’s like an exorcism that takes place, and I’m at the heart of it, and it’s just phenomenal.”

Part III: ‘Tweaked by Zorn’: The Mr. Bungle Alliance

For the members of Mr. Bungle, the experience of entering Zorn’s orbit was somewhere between boot camp and grad school.

Trey Spruance recalls that as producer of their debut, Zorn helped them to “clean some of our mess up.”

“One of the things that he had done on that first record was, he objected to the dirty guitar tones, ’cause we’re just these idiots from Eureka [California]; we don’t have any real equipment,” Spruance recalls. “Really just crappy amps, crappy instruments. So he hired out a Marshall half-stack, and I retracked all of the dirty guitar sounds on the records, because they were just not satisfactory. We had no idea what the fuck we were doing in the studio.”

The musicians may have felt green, but Zorn saw something in them early on. His initial meeting with them would mark the beginning of a vast string of collaborations — as well as, they all emphasize, close friendships — with Bungle members Spruance, Mike Patton, and Trevor Dunn, which started with 1992’s Elegy and have continued to the present day.

“I was working in San Francisco, recording some record, and the Bungle guys wanted to come and meet me,” Zorn recalls. “I came to the studio and I finished a take, and I came out into the meeting room and they were all sitting there with shit-eating grins on their faces, and you look in their eyes and you get a sense of who these people are. And I immediately said, ‘These are serious musicians; these are guys that are really open-minded; they’re interested in what I’m doing,’ and that’s where the Elegy record came about.”

Like the earlier Spillane, Elegy was an album of Zorn’s so-called “file card” pieces, which are assembled in the studio from a collection of musical or conceptual ideas, written out on actual notecards. Sonically, Elegy ranged from contemporary chamber music — with material quoted from “Le Marteau sans maître,” a challenging 1955 piece by the French composer Pierre Boulez — to unsettling soundscapes that played like movies in your head.

For Patton, the period was a key turning point. In the fall of 1991, when he recorded Elegy, he was just a year removed from a Top 10 hit with Faith No More, a band in which he played more or less a conventional rock-frontman role. Earlier that year. he’d been out on the road with Naked City, taking Eye’s place and responding to Zorn’s live cueing, and now he found himself being called on to improvise in the studio, an experience that caught him totally off guard.

“I didn’t know that shit at the time,” Patton says. “I was really ingrained into being a singer, which to me was a whole different chapter than I was aware of. And [John] was just like, ‘Do whatever you want!’ I’m like, ‘Whatever I want, what?!‘”

For Spruance, free-form music-making wasn’t so foreign, as he and Dunn had improvised together in high school and studied jazz at California’s Humboldt State University. But during the Elegy sessions, Zorn put the guitarist on the spot in a different way.

“He had quotations from Pierre Boulez, ‘Le Marteau sans maître,’ and he fucking put the guitar part in front of me,” Spruance says with an incredulous laugh. “I fucking played the hardest classical-guitar piece, probably most challenging in the whole fucking world. I had no time to prepare; he didn’t give me preparation for it. He’s like, ‘Here, you can do this; do that.’ I was like, ‘What the fuck?!’ So, like 10 minutes before we hit the record button, I’d be woodshedding as fast as possible. I’m not the best reader in the world; he knew that. And we’d get going on it, and he’s like, [mock-taunting] ‘See, you can do it, why are you doubting yourself? Look, you just did it, you fucking asshole!’ This kind of thing. So he puts you on the spot, and he somehow knows that you can do shit. …

“He knows how to inspire people, how to frighten people,” Spruance continues. “I mean, he’s really good at frightening people in the right way. He’s fucking super good at it, without being a bully. It’s, ‘Here’s your chance, go!’ But it’s not just, ‘If you fuck up, you’re done.’ It’s more like, ‘You can do it, I know you can do it, we both know you can do it, so fucking do it!’ That kind of thing. It was a real encouragement, actually.”

“[John] puts you on the spot, and he somehow knows that you can do shit.” —Trey Spruance

Zorn’s influence is unmistakable on Mr. Bungle’s later work, especially 1995’s Disco Volante, an album that effortlessly traverses metal, jazz, and many other styles, and moves at will between tightly constructed songcraft and abstract texture. And especially for Patton, his contact with Zorn would spur him to explore his most extreme musical impulses.

Patton’s first solo album, Adult Themes for Voice — released on Zorn’s Tzadik label in 1996 — came about at Zorn’s request. Recorded in hotel rooms while on tour with Faith No More, it’s an encyclopedia of alien sounds, sometime subtle, sometimes explosive, generated entirely by Patton’s voice, and it essentially fast-tracked the singer into the position of the elite experimental-vocal wizard that he occupies today.

“He’s the guy who said, ‘You should do a solo vocal record,’” Patton says of Zorn. “He’s like, ‘You got the pipes, you can do it.’ I’m like, ‘Uh, what? What would I do without a backing band?’ I didn’t understand. And slowly I began to learn that, oh, what I have is actually an instrument too; it’s not accompaniment; it’s not frosting on the cake. It’s an instrument, and I should showcase it. Not show off, but make it real, you know? And that was his idea. I would have never done that record without him, and that’s the weirdest fuckin’ record I ever made, by the way.”

Patton says the same of Fantômas, the singer’s all-star art-metal juggernaut with Dunn, Lombardo, and Melvins guitarist Buzz Osborne. Their 1999 self-titled debut and 2005’s Suspended Animation took Naked City’s concepts of frenzied Carl Stalling-isms and tiny sound blocks to terrifying new extremes, while 2001’s The Director’s Cut reimagined film themes à la Zorn, and 2004’s Delìrivm Còrdia ventured deep into sonic cinema in the vein of the composer’s file-card pieces like Spillane and Elegy.

“I wouldn’t have Fantômas without Zorn, and without Zorn being a close friend, a family member,” Patton says. “He gave me, somehow, the courage to do something like that.

“Musicians, man, some of us get really caught up in what we’re doing and where we fit, and he always gave me this weird sense of confidence — that maybe I shouldn’t have had, but he gave it to me — to try shit,” the singer adds. “How do you define that? That’s a teacher, or a seeker, an inventor and someone with a level of focus that, at least at the time, I did not have.” (Patton also notes that Zorn, who has released hundreds of albums of his own and by others on Tzadik since 1995, gave him the idea to start his own label — Ipecac, co-founded with Greg Werckman in 1999 — in order to release Fantômas’ self-titled debut.)

Zorn and Patton have gone on to collaborate on numerous projects. The singer fronted a briefly reunited Naked City live in 2003, and contributed vocals to expanded reissues of both that band’s Grand Guignol and The Big Gundown. The two also formed the improv trio Hemophiliac with Ikue Mori, drummer of the No Wave band DNA and another longtime Zorn associate, on electronics.

But their most ambitious joint venture to date might be Moonchild, a band that, much like Naked City, mutated radically across its lifespan as Zorn kept raising his compositional bar. While it touched on similar extremes as that group — for example, bruising heavy prog that can sound like the harsher moments of early-Seventies King Crimson, convulsive improvisation, and quasi-ritualistic mood pieces — its episodes are more sustained, its structures more conventionally songlike. (Another difference is that in Moonchild, Zorn’s role was more that of composer-conceptualist than performer; he played saxophone with the band only occasionally.)

Moonchild’s lineup mixed and matched players from various eras of Zorn’s career: Patton; Joey Baron; and Mr. Bungle bassist Trevor Dunn, who’d played in several of Zorn’s Masada ensembles, as well as in his game pieces, on soundtracks the composer wrote, and in his exotica-influenced ensemble the Dreamers. Guests like Mori, John Medeski, fellow keyboardist Jamie Saft, and multifaceted guitar master Marc Ribot later entered the mix. For the first five of Moonchild’s seven albums, released from 2006 through 2014, Patton utilized his full whisper-to-scream range while operating entirely without lyrics.

“It started as a compositional challenge, as a song cycle, songs without words,” Zorn says of the group. “I want to work with Patton more; Patton was very hungry to do more work together. ‘OK, so let’s start it with just bass, drums, and voice.’ Amazing. And I came in with nothing written down. I sang the parts; I talked the parts; I described what we wanted, this and that. I was very, very specific, especially with Patton’s voices, of what I was looking for.”

Unlike Naked City or other Zorn projects that Patton had been involved with, Moonchild was a fresh compositional venture launched with him in mind. “So I took it really seriously, and he pushed me to the brink,” the singer says.

“I would pass out in the studio,” he continues. “Here’s the way that some of those sessions would go: He’d be in the control room; I’d be in the playing room, where I was singing, and he’d look at me and he’d give me direction, by his hands — and this is another thing that Zorn taught me, was visual cues: invaluable, and I use them to this day with my own bands. … But in some of those Moonchild sessions, I would not breathe correctly and pass out. He would extend a scream over, like, 45 seconds, or something. And I’ll get into the scream, and he’ll go, ‘Go, go, go, go, go,’ and I’ll just keep going, and boom, I’m out. So I think that speaks a lot to pushing the limits of a musician, and that was his thing.”

Dunn says it’s been fun to watch his old friend Mike Patton get “tweaked by Zorn” over the years, and adds, “I got tweaked by him in my own way.” He speaks about Zorn almost as one would a tough sports coach, who asks a lot but gives a lot in return.

“Definitely, for me, he instilled a certain kind of energy that I think, sometimes as musicians, it’s easy to lose,” the bassist says. “You get a little bit lazy with things and you fall into patterns. But no, you gotta be on all the time. It’s definitely a challenge, but you have to be up for the challenge, too. And the fact that he’s really trying to get the most out of you, get you at your best and most creative and energetic, it’s really something to have a bandleader do that.

“At the end of the day, if you can get through something that he’s brought to the table, then he’s gonna say, ‘Oh, man, I can push it another step next time.’ I’ve definitely improved as a musician by working with him, and also working side by side with all these other musicians who are also being pushed.”

Much as Patton says he’s taken visual-cueing and other techniques he learned from Zorn and applied them in his own projects, Baron and Dave Lombardo also credit the composer with expanding their creative skill sets.

For Lombardo, coming into his own as an improviser helped him to stay inspired once he returned to Slayer in the early 2000s. “I started finding myself in that machine, redundant world of performing the same songs night after night,” he says. Before going onstage each night, the drummer says, he would sit in the back of the tour bus and listen to a variety of different music, from jazz to Gypsy music and blues, and then try to carry that spirit with him into the Slayer set. “When I played onstage, I would throw some drum rolls in there that would basically make the other guys in the band turn around and say, ‘What the fuck was that?’” he recalls. “They didn’t know where that drum roll or that interpretation of a drum roll I had written in ’88, or whatever, came from, but by listening to different styles of music and fine-tuning my ability to improvise, I was able to kind of wake the guys up onstage.”

Beyond his personal growth, Lombardo credits Zorn with opening up a line of communication between the greater jazz and metal communities that simply didn’t exist before. “He has been the bridge for the connection between two genres that probably would never have co-inspired each other,” Lombardo says. “He’s shown that it can be done. There’s only good music and bad music. … It’s all inspirational; you just have to find the beauty within these pieces and draw from it. And that’s what he’s done; he’s helped us to realize that there shouldn’t be a style of music that’s not explored and used to inspire you to create something. It’s all relevant, basically.”

“John has helped us to realize that there shouldn’t be a style of music that’s not explored and used to inspire you to create something. It’s all relevant, basically.” —Dave Lombardo

Just as working with Zorn gave Lombardo a new confidence in his ability to improvise, Joey Baron found that, post–Naked City, he was able to draw on the energy of hardcore, no matter what the context.

“I think it’s really good, [John’s] way of pushing people outside of their box, because when we all go back to doing what we do in our own pursuits, it has a profound effect,” Baron says. “And I noticed that tremendously, just that energy or that abrupt, blatant surge of power that that music has, really influenced me and it helped me whenever I played any kind of music. It was a nice addition to have in the toolbox.

“I wouldn’t strategically say, ‘OK, when we play “All the Things You Are,” I’m gonna do a blast beat on the bridge,” he stipulates with a laugh. But he notes that when playing in more traditional jazz settings, this kind of know-how might come into play in subtler ways. “I would play with all these groups that were nowhere near the amount of volume level, and completely different focus, completely different type of music,” Baron says. “But whenever I’m playing music, if the music calls for something where I can make my own decision about something, that element was in my toolbox, and if I felt, ‘Yeah, this could go this way,’ I would do it.”

Part IV: ‘This Alchemical Mix’: The Next Generation

In February 2020, an unusual band took the stage at an intimate Brooklyn venue called the Sultan Room. The latest example of Zorn playing musical Cupid, the trio brought together guitarist Matt Hollenberg and drummer Kenny Grohowski — respective members of vanguard extreme-metal outfits Cleric and Imperial Triumphant — with organist John Medeski, a hero to fans of groove-oriented jazz, thanks to his work with Medeski Martin and Wood. During a commanding yet exuberant set, the group presented music from its six prior Zorn-composed studio albums under the name Simulacrum, in which full-tilt death-metal riffage flows in and out of simmering postbop, disjointed improv, and dramatic, classical-like themes.

In some ways, this band, formed in 2015, feels like the ultimate chapter in Zorn’s jazz-metal odyssey. It grabs elements from throughout his history — his Nineties work with organist Big John Patton, a veteran of the Sixties Blue Note roster; the dynamic extremes of Naked City; the more patient compositional arcs of Moonchild; even the soothing textures of projects like the Dreamers — and rolls them into a holistic hybrid. A listener looking for a way to access this specific sector of Zorn’s work would do just as well to start with Baphomet, a new, 39-minute Simulacrum suite that unfolds with prog-like grandeur, as with Naked City.

“Absolutely,” Zorn answers, when asked if he views Baphomet as a culmination of this area of his output. “It brings everything together, because I’m an additive person. … A decision, once it’s part of who I am, it stays. I keep adding. I’m not a fashion guy, who just adds this and then throws the other thing away.”

“Simulacrum is amazing. It’s absolutely ripping; it’s killing,” says Mike Patton. “And it’s funny because I hear a lot of Moonchild in there, but it’s on a different curve. I mean, when I listen to [Baphomet], I think, ‘Fuck, I want to sing on this!’ But that’s not the point; the point is [John’s] perfecting and crafting a similar model, and I think that’s amazing.

“That dynamic was just wild for me,” the singer adds of the later era of Moonchild with Medeski that paved the way for Simulacrum. “Like, ‘Wait, bass, organ, drums, and vocals? That’s your fuckin’ instrumentation?!’ And guess what? [Zorn is] such a fuckin’ master that it worked. And he’d use the organ as a bass sometimes, or guitar sometimes. I mean, all I can tell you is, it was really, really exciting, and a great band. But like I say, Simulacrum is the next level from that. And taking my shit out of it, I think it’s compositionally way more advanced and more — just, now. It’s very now.“

Backstage before their Brooklyn show, the three members of Simulacrum talk through how unlikely it is for them to be sharing a stage — let alone to have released seven studio albums and a potent live disc, Beyond Good and Evil, as a band in a span of just five years.

“I love metal, but unless you go really back, keyboards are not a big part of it,” says Medeski, 54. “So [Simulacrum] is an interesting blend of stuff. … And it gives an opportunity to be in a vibe that I don’t get to do anywhere else in any way.”

“The three of us really don’t start in the same place musically, but there’s these little nodes that we all share in the greater web of music and journey,” adds Grohowski, 37, who in addition to playing experimental black metal with Imperial Triumphant also gigs with progressive jazz artists like Igor Lumpert and Andy Milne, and British fusion outfit Brand X.

“I haven’t thought about this before, but just thinking about it now … where we connect is a unique thing, and even where we don’t connect, but how we affect each other musically,” Medeski says. “And this is where Zorn is a genius at putting people together and putting elements together. Like, who would have fuckin’ thought of this? Only him. Who would have had the balls to actually do it and then write seven more records and really develop it? Nobody.

“And as a band, everybody’s sort of stepped up to the plate with this music, ’cause it’s really fuckin’ hard — like, really hard,” the keyboardist continues. “And I think for Zorn, the fact that everybody stepped up is like, ‘Oh, you can do that? Well, try this!’ ‘Here’s an uppercut.’ ‘Here’s a body blow.’ Because of how fun it is when we get together, he’s inspired.”

Hollenberg, a 36-year-old guitarist who came onto Zorn’s radar around a decade ago after Trevor Dunn passed Zorn a Cleric CD, agrees. “It’s almost like he’s a boxing coach or something,” he says. “He really wants to push everyone. It’s like a mix of Garry Shandling and Gordon Ramsay.”

“There’s no one else that I work with that they call me up and say, ‘Hey —’ and I just say yes before I even hear what it is,” Medeski adds of working with Zorn. “I don’t even ask, ‘What does it pay?’ I don’t ask anything. I just say yes. ‘Cause I know it’s gonna be great.”

“I’ll co-sign on that,” says Hollenberg.

“There’s no one else that I work with that they call me up and say, ‘Hey —’ and I just say yes before I even hear what it is.” —John Medeski

That Zorn still inspires this kind of loyalty — not just from his peer group and musicians like the Mr. Bungle crew, who came up in his immediate wake, but from much younger artists — is striking. Hollenberg, Grohowski, and their peers are players who have essentially grown up in the world Zorn has helped to bring about, where artists from the spheres of metal, jazz, and beyond regularly communicate and cross-pollinate. Consider not just Imperial Triumphant, a black-metal trio that builds improvisation into its songs, and Cleric, a massively heavy band given to drastic shifts in texture and style, but Starebaby, a band of jazz virtuosos drawing on their shared love of extreme metal to create a new mutant sound, or avant-metal guitarist Mick Barr’s collaborations with seasoned improvisers like Marc Edwards, Jon Irabagon, and Mike Pride. These musicians, and others like them, all operate in a distinctly post-Zorn sphere. In some cases, their own hybrid skill set may have even been directly inspired by him.

Take the guitarist Wendy Eisenberg. It would be impossible to put any kind of overarching label on their work to date (Eisenberg uses gender-neutral pronouns), which includes exploratory acoustic playing and high-energy art punk with bands such as Birthing Hips and Editrix, and — as heard on The Machinic Unconscious, a 2018 Zorn-produced album on Tzadik — anything-goes electric improv with Trevor Dunn and drummer Ches Smith. According to Eisenberg, 28, it was an early exposure to Zorn’s work that helped them establish such a broad aesthetic and range at an early age.