Hardcore, the genre and scene, has always been about breaking down barriers.

Anyone who’s grown up watching bands carve up community halls and suburban carparks will tell you that, at its best, it has resisted hierarchy, prized mutual care, and trusted its community to self-regulate. Values like that don’t always survive at scale, so when Grammy-nominated hardcore band Turnstile played two Sydney shows on consecutive nights last week, one with a barrier and one without, it felt less like a coincidence and more like a thesis statement.

What happened across Sydney’s Hordern Pavilion and Metro Theatre was part chaos, part cultural exchange, and also a demonstration of how heavy music has learned to survive visibility without losing its ethics.

Rocking up to the Hordern last Tuesday evening, the diversity of the audience was immediately striking. Not just in age (it’s worth noting the event was all ages), but in energy. Clear hardcore lifers in well-worn band tees stood alongside people who looked like they’d never set foot in a mosh pit before. Fashion kids. Pop-adjacent fans. Groups of friends clearly introducing someone to this world for the first time. Still, it didn’t feel fragmented. Opening bands Basement and Feel the Pain delivered sets perfectly engineered for throwing arms, the kind of physical warm-up this music demands.

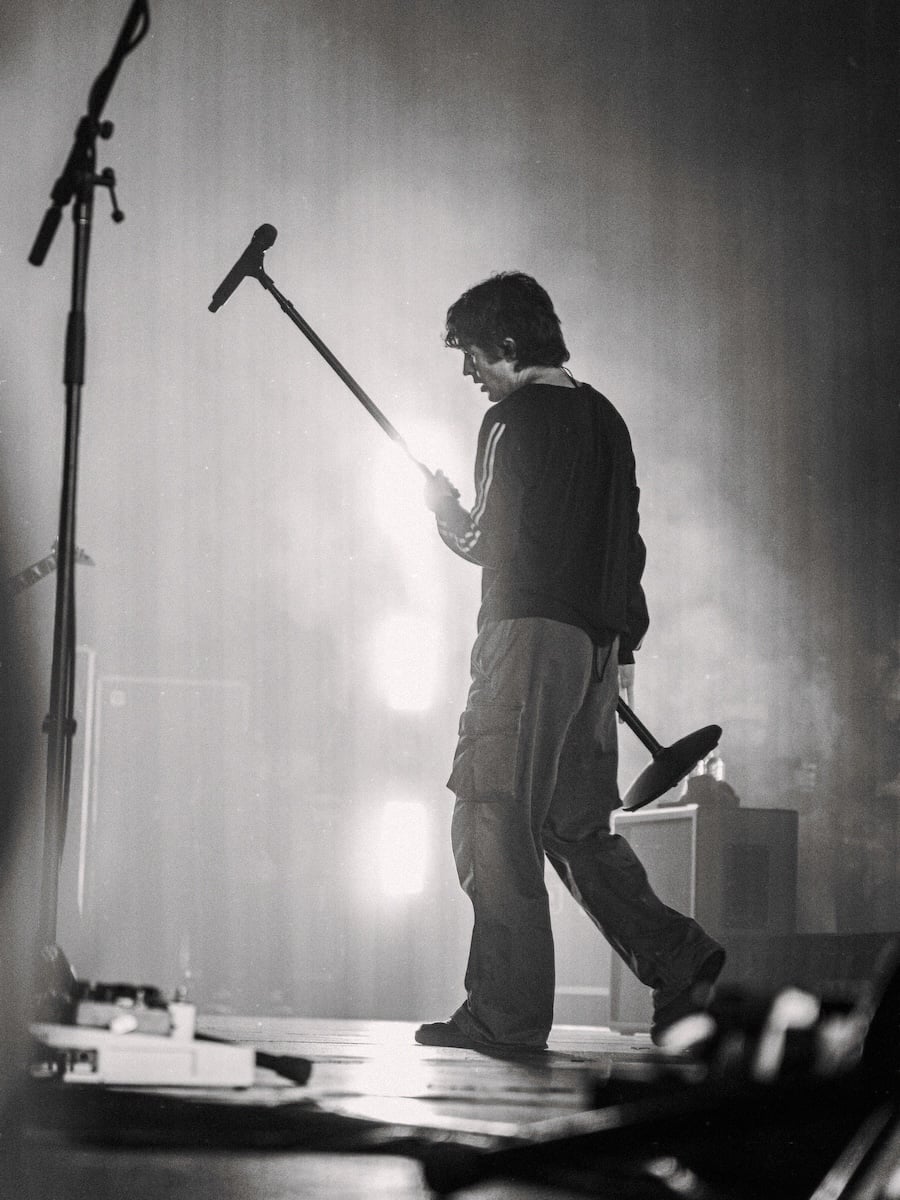

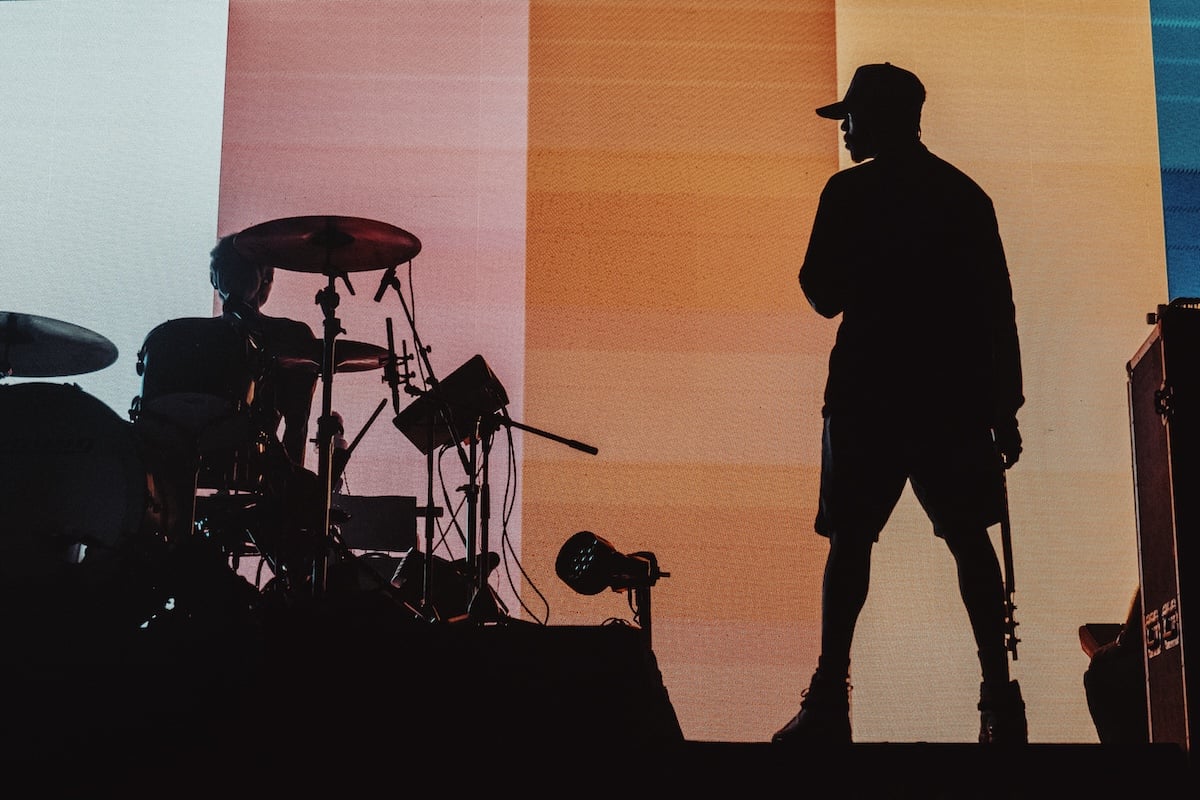

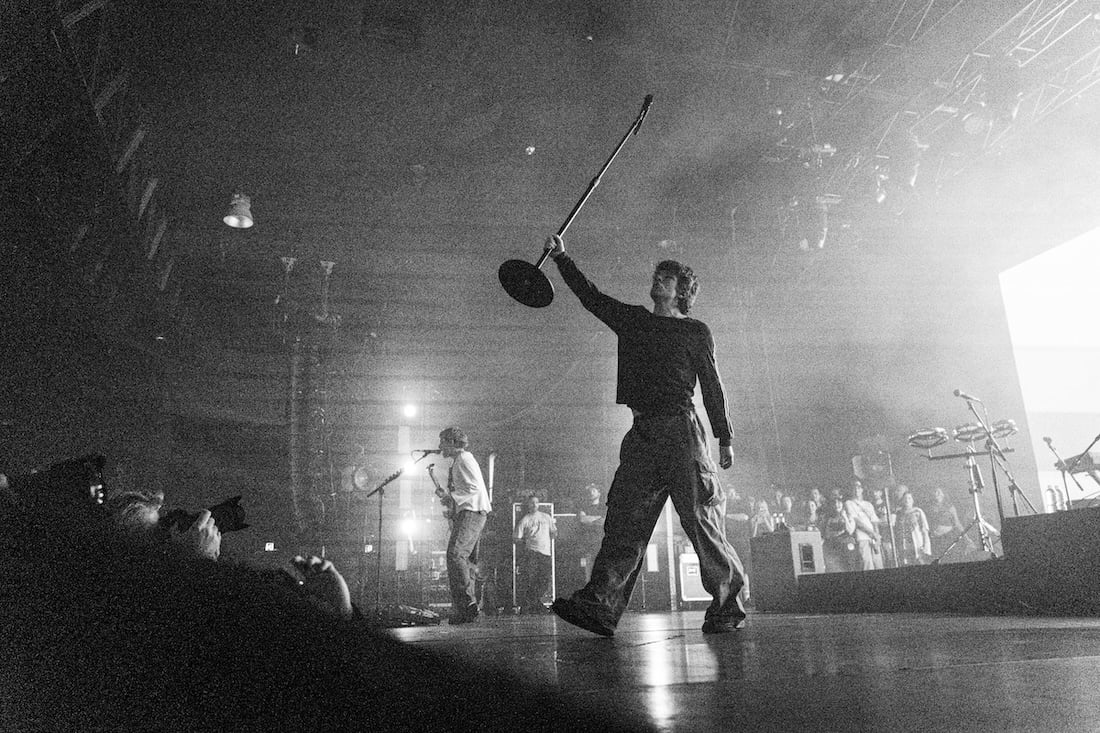

Once Turnstile took the stage, the room locked in entirely. That kind of full-bodied attention is rare at shows of this scale (and something that’s hard to conjure within the Hordern’s expansive space). Thousands of people not just watching, but listening and moving in unison. You could feel it physically: the collective intake of breath before the band’s now iconic on-stage rainbow (a subtle nod to Hendrix) ignited the space. The barrier was up, but it didn’t neuter the energy of the mosh. The undeniable feeling of presence in the room wasn’t aggressive, but a shared understanding that this intensity only works if everyone agrees to look after one another.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

If hardcore once built its mythology around endurance, on how much you could take a hit and keep going, this felt like something else entirely. A reframing in a room full of people that trusted each other enough to let go. And yet, as expansive and affirming as that first night felt, it still operated within familiar architecture. The stage had a barrier. There were clear roles. The band and audience remained physically distinct, even as the emotional distance collapsed.

Which is why the following night mattered so much.

Wednesday’s show at the Metro Theatre hadn’t been on the books for months. It came together fast, with conversations beginning just days before Christmas and tickets sold out in under 20 minutes. In 2026, these facts alone would be impressive, but even more striking was that all profits were directed to grassroots Aboriginal women-led organisation First Nations Response. It was a clear statement of community values embedded into the structure of the night itself.

And then there was the room.

Unlike the Hordern, Metro Theatre is intimate, vertical and built for proximity. Crucially, the barrier at the front of the stage was removed for this event, which meant no enforced separation between performer and participant. True to the spirit of hardcore, the stage belonged, temporarily, to everyone. As soon as openers Primitive Blast took to the stage, the crowd made it very clear that they weren’t just there to watch, but to make up a crucial part of the show.

It’s worth noting that Metro Theatre has, in recent years, rejected similar barrier-down requests for shows in other genres. The decision to remove it here wasn’t automatic: it was a gesture of trust. A venue’s acknowledgement that hardcore crowds, for all their volume and velocity, have a long history of self-policing.

Both Sydney shows also featured local hardcore outfit Speed joining Turnstile on stage in moments that landed less like a guest appearance and more like a quiet affirmation of lineage (Sydney shit, motherfuckers!!!). Speed aren’t just a local opener elevated for hometown goodwill. They’d spent time on the road with Turnstile last year in the United States, playing room after room across the country, absorbing and contributing to hardcore’s global circulation in real time.

Seeing that history fold back into Sydney felt significant. It’s a massive nod to Australia’s homegrown hardcore scene and a culture that has retained its literacy as it’s grown. A community where people know how to be present, how to hold space, how to meet intensity with care rather than chaos. Speed’s presence acted as a kind of proof that Australian hardcore isn’t simply consuming the global moment, but actively shaping it. In this context, the barrier coming down on night two didn’t feel like a risk taken. It felt like recognition earned.

If the Hordern show demonstrated hardcore’s emotional maturity, Metro Theatre revealed its structural integrity. This was a community trusted with freedom, and visibly capable of holding it and welcoming newcomers. The pit wasn’t controlled so much as collectively maintained to minimise injury. When things got too wild, the room adjusted. When someone needed help, it arrived instantly.

This wasn’t nostalgia for some imagined golden age. It was a living, functioning ecosystem.

Seen side by side, the two nights formed a kind of cultural proof. One showed how hardcore can expand without losing coherence. The other showed why, even now, venues are willing to hand it the keys.

In an era where live music is increasingly regulated, insured, and risk-managed in the name of safety, it’s quietly radical that one of the biggest hardcore bands in the world can still stand in front of a room and say: we trust you.

And the crowds sing it back.