DMX’s first foray into major-label hip-hop was a failure. In the early 1990s, he released “Born Loser,” a loping anti-anthem for the down-and-out: “Even when I was little, nothing went my way/I got beat up and chased home from school every day,” DMX rapped. The single’s tone turns defiant — “Since I was born with no hope, I ain’t got nothing to lose” — but that didn’t help the track’s commercial fortunes.

While “Born Loser” missed the charts, it still caught the ear of a young New York radio DJ named Funkmaster Flex, who played the song on the airwaves at the station WBLS. “His delivery was aggressive, his voice was aggressive,” Flex recalls. When DMX returned later in the 1990s with a series of choppy, roiling hits for Def Jam — he cracked the Top 40 for the first time as a solo artist with “Get at Me Dog” in 1998 — Flex was at the New York hip-hop institution Hot 97, where he continued to support the rapper. DMX was on a pair of the Top 15 most-played singles from Hot 97 in 1999, according to Mediabase, and had another Top 10 on the station the following year.

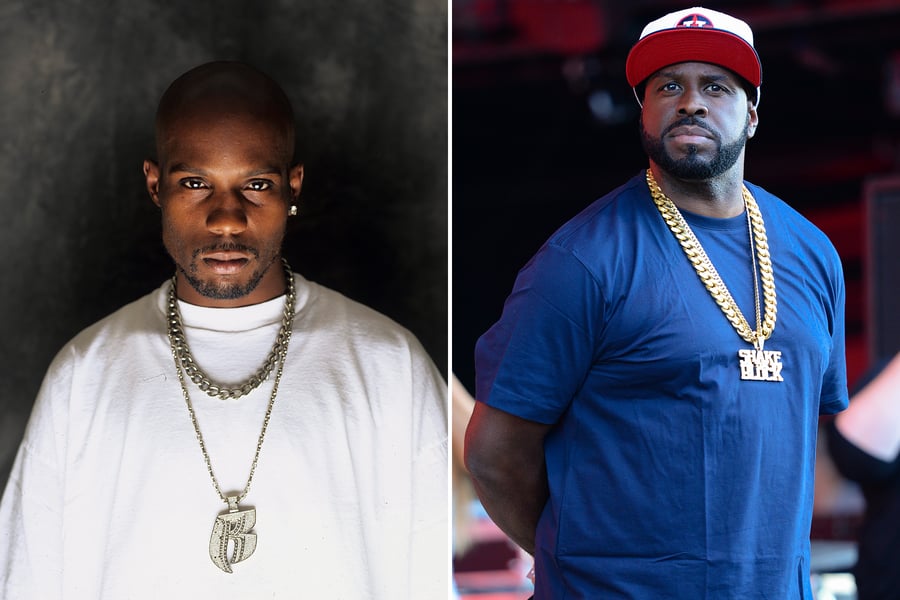

The two men became musical collaborators — DMX contributed to several Funkmaster Flex mixtapes, spawning a pair of minor hits — and shared a love of muscle cars. Following the rapper’s death last week after a heart attack, the DJ spoke with Rolling Stone about DMX’s career and his contributions to hip-hop.

I grew up in the Bronx, but after a couple years I moved to Yonkers. This had to be 1990, 1991. Not long after that I met DMX, when he had that “Born Loser” song. I was on WBLS in 1990. Before that song was on Ruffhouse, it was an independent record they pressed up. That’s when I played it, and that’s how I met him.

I didn’t know his level of dedication at the time, didn’t know what he would turn into, that he was gonna be that. But there weren’t that many people coming out of Westchester, out of Yonkers, then. In 1990, you’re talking a lot about A Tribe Called Quest, you’re talking a lot about De La Soul. It wasn’t an aggressive period for hip-hop. But he was aggressive.

DMX never changed his style of rapping. It just came into style by the later half of the 1990s. By then you had Onyx, other things that were aggressive. And that set the tone for DMX. When he got on, he was already 26 or 27 years old — he wasn’t a young rapper. He was a veteran that blossomed late.

[P. Diddy’s label] Bad Boy was shining bright at that time; they were at the forefront of the music game. [Jay-Z’s label] Roc-A-Fella was a little closer to [what] Biggie and Puff [were doing]. I don’t want to say Jay was similar to Big, but they weren’t about tank tops and motorcycles, which was what Ruff Ryders was. DMX was totally someplace else. One of one. Gutter. Street.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

He was on two or three of my albums. He was on “We In Here,” and he was on “Do You.” He had a great freestyle on [The Mix Tape] Vol. III. I used to work on his car sometimes, too. He didn’t live far from me, like two towns over. In his town, he’d drive those cars late. He liked muscle cars like I liked muscle cars. He was making a lot of noise in that town, a lot of noise.

I went to Canada with him once, we shot a video there. DMX didn’t have a license. Just to talk to him about the song, I had to go to Canada and ride around with him. He was exactly one inch from every turn, he would miss it by one inch. It was like, “Damn, this guy’s gonna kill us, man!”

I didn’t get on a private plane with him once, because he wanted me to ride with him someplace, but he had these remote controlled cars with fuel on the plane! I’m like, “I’m not riding with you and the cars — what’s gonna happen in the plane?” That plane goes down, DMX is gonna live guaranteed. Everyone else will die.

I want to say this in the best way possible. What I see people going through in the music industry is happiness or depression, that’s what I see in the business. I don’t want to say people don’t check on each other, but I don’t know if the powers that be who financially benefited from an artist like DMX — when you’re taking care of yourself, trying to get to a better place, there’s no money being generated, you know? I think sometimes there was a push to get him back on the road, get him back in the studio, get him back on the road, get him back in the studio. DMX is coming home; we’re putting him on the road. No one took advantage of him. But he sold millions of records — that fed a lot of people.

He was a good guy. Swizz Beatz put something on his Instagram that was very true, though maybe I didn’t realize it until Swizz said it: He said DMX “lived for everybody else but him.” He did. Do I think he was happy while he was doing it? I’m not sure. I always wondered what was troubling him. But you can tell when somebody has a good heart, from conversations, interactions, how they move. I always felt that from him. He was a street kid with a good heart.

From Rolling Stone US