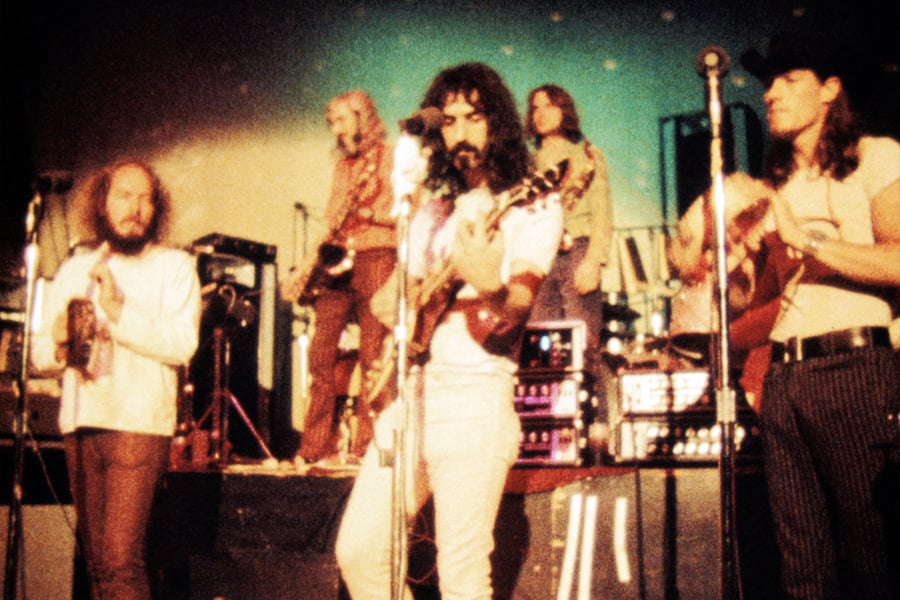

It’s a happy “Franksgiving” for Zappa fans as director Alex Winter’s years-in-the-making authorized documentary Zappa has finally arrived. Touted as having unprecedented access to Zappa’s immense vault, the documentary is packed with never-before-seen footage of the legendary rock polymath: composer, guitar god, father to the Mothers of Invention, free-speech activist, humorist, satirist, author, occasional actor, beloved late-night guest, and Czechoslovakia’s one-time Special Ambassador to the West on Trade, Culture, and Tourism.

Zappa released more than 60 albums during his lifetime, so a two-hour documentary barely scratches the surface of his story; you’d need something Ken Burns–sized for that. Still, the unearthed footage should be enough to make completists happy, while the documentary itself serves as a perfect roadmap for future generations of fans, covering everything from Frank’s strange childhood to Freak Out and his 1993 death.

Like Zappa’s oeuvre itself, the documentary isn’t without flaws. Both diehards and casual fans may bristle at the fact that the Seventies stretch that produced some of Zappa’s most lasting work — Overnite Sensation, Apostrophe, One Size Fits All, Joe’s Garage, etc. — is reduced to 30 seconds of screen time. However, Zappa does exactly what it sets out to do: establish its subject as one of 20th-century music’s most innovative and uncompromising composers.Although nothing too revelatory comes to light in the film — at least for longtime devotees — here are some things Zappa neophytes might learn from the documentary:

1. Zappa’s vault makes Prince’s look like a safety deposit box.

There have been glimpses into Zappa’s vaults — Classic Albums specials dedicated to his Over-Nite Sensation and Apostrophe LPs have teased the epic scope of the collection, while the Zappa Family Trust’s steady flow of semiannual archival releases hints at the amount of indispensable audio that still lingers in there. But on the visual end, Zappa’s private collection has never been excavated to this extent. “Most of this material has never been seen,” the documentary notes early on.

Zappa also provides quick snippets of some of the vault’s more intriguing audio material, including a tape labeled “Clapton at Home” — where the two guitar gods played around at Zappa’s house — as well as another tape capturing the time Zappa and Captain Beefheart had “a jam in the basement.” The doc also unearths what could be the most pristine footage of the Mothers’ 1971 jam with John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

However, the film’s rapid-fire editing — perhaps an attempt to squeeze in as much vault footage as possible — is sometimes too disorienting, which is ironic because …

2. Zappa originally dreamed of being a film editor, not a musician.

“I became obsessed with editing, and I would edit just because I liked to edit,” Zappa says in voiceover. “I would splice an 8mm film that was in the house to anything else.” One such victim of Zappa’s filmic Frankenstein-ing would be his parents’ own 1939 wedding movie, which Zappa punctuated with insert shots of flying saucers and nuclear holocaust. The documentary, thankfully, unearths this early evidence of mad genius.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Zappa’s love of editing would ultimately weave its way into his music as the guitarist pioneered what he coined “xenochrony,” in which he deposited moments captured onstage — often breathtaking guitar solos or a certain drum rhythm — into his studio recordings. Zappa would also later satiate his editing fix with 1983’s The Dub Room Special, which he constructed in a Burbank post-production facility.

3. Unsurprisingly, the man who penned “Let’s Make the Water Turn Black” had a weird childhood.

The son of a chemist, Zappa states that he learned how to make gunpowder at the age of six, and that his father’s occupation at a Maryland factory where chemical weapons like nerve gas were made left its mark on his psyche and worldview.

“Everybody that lived in the project had to have gas masks in their house in case the tanks of mustard gas broke,” Zappa says while notating sheet music. “The toys I remember growing up with were the little chemical beakers my father would bring home, and the gas masks that were hanging in the hall closet.” (The gas mask would be a reoccurring motif in the Mothers’ music, captured on record in the Debussy-referencing “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Sexually Aroused Gas Mask.”)

After the Zappas moved to California, Frank’s predilections toward explosive chemistry continued. “The last experimentation that I did with explosives was when I was about 15 years old,” Zappa says casually in an archival interview. “I mixed up this quantity of powder which consisted of regular black power and then flash powder, which is 50 percent zinc, 50 percent sulphur, mixed with sugar, and attempted to set fire to the high school I was attending.”

4. A magazine article about “ugly music” ignited Zappa’s interest in composition.

As Zappa reveals in the documentary, his parents were “opposed to any involvement in music that I might be interested in,” but a magazine article about record store magnate Sam Goody and his ability to sell “ugly music” — specifically, The Complete Works of Edgard Varèse, an avant-garde French composer — piqued Zappa’s interest.

“It was because of that Varèse album that I read about in the magazine, and hearing ‘Ionisation,’ that I [began] writing orchestra music. I had no interest in Beethoven, Mozart, or any of that stuff; it just didn’t sound interesting to me. I wanted to listen to a man who could make music that strange.” Zappa adds that he wrote orchestra music before he ever attempted a rock & roll song. Varèse’s adventurous approach to music would remain the chief influence throughout Zappa’s career.

It was Zappa’s high school friend Don — or Don Van Vliet, a.k.a. Captain Beefheart — who introduced teenage Frank to R&B, doo wop, and another of Zappa’s major influences, Johnny “Guitar” Watson. Zappa said of the guitar, an instrument he would later lord over, “Once I figured out that the pitch changed when you put your finger down on the fret, I was hell on wheels.”

5. Zappa was prolific except in the friends department.

“I don’t have any friends,” Zappa admits in an interview — shown in Zappa — a few years before his 1993 death. The documentary tackles how the artist always prioritized his own music above personal relationships, even keeping his longtime collaborators at arm’s length.

As longtime Mothers of Invention percussionist Ruth Underwood says in the doc, “I used to think, ‘OK, he’s called me here’ — and I don’t mean in the early days, I mean in full flower of playing with him — we’d talk for a minute and then there isn’t even a ‘Thanks for coming by’ or ‘See ya later.’ He would just turn the other way, and I would be waiting for him to turn back and say [something], but if he did turn it back he’d go, ‘Oh, you’re still here?’ Like I was dismissed, without even being dismissed… You can interpret that as being, ‘What a fucking self-centered asshole,’ but I think that he was so single-mindedly needing to get his work done.”

“My desires are simple: All I want to do is get a good performance and a good recording of everything that I ever wrote so I could hear it, and if anybody else wants to hear it, that’s great too,” Zappa says in an archival interview. “Sounds easy but it’s really hard to do.”

6. He had an unusually understanding wife.

“I married a composer. I don’t know what he is to anybody else, but to me he was a composer. And you have to be out of your mind to begin with to take it on,” Zappa’s widow Gail says in the film during an exclusive interview recorded prior to her 2015 death.

The documentary covers Frank and Gail’s sorta meet-cute moment — they were set up by the infamous “Suzy Creamcheese” for the sole purpose of Frank getting laid — and the tribulations their union faced. It was a complicated marriage where Frank would carry on relationships, sometimes flagrantly and in full view of the press, with other women while on the road.

In one archival interview, the married Zappa admits, “I’m a human being. I like to get laid. I mean, you have to be realistic about these things: You go out on the road, you strap on a bunch of girls, you come back to the house and find out you got ‘the clap,’ what you gonna do? Keep it a secret from your wife? So I come back to her and I say, ‘Look, I got the clap, go get a prescription.’ So she goes out and gets some penicillin tablets, we both take ’em, and that’s it. She grumbles every once in a while, but y’know, she’s my wife.”

While not turning a blind eye to Frank’s misdeeds, Gail’s advice to those considering marrying a musician: “Don’t have those conversations.”

7. The Beatles kinda screwed Zappa over.

The documentary reiterates how influential Zappa was on the Beatles — “They’ve explicitly said ‘Sgt. Pepper was our attempt to make our own Freak Out,’” guitarist Mike Keneally says — but the Fab Four weren’t exactly grateful for the inspiration. It’s been long-documented that the release of the Sgt. Pepper-mocking We’re Only in It for the Money was delayed pending Beatles’ approval, but in Zappa we hear the disappointment on the matter in Zappa’s own words.

“MGM was panic-stricken that they would be sued by the Beatles, and wanted legal assurance that the Beatles weren’t going to harm them. … All the legal gyrations took about 13 months,” Zappa says of the We’re Only in It artwork. “I know I talked personally to McCartney at one time and said … ‘Can you do anything to help me?’ And it was like he was on the other end of the line, ‘You mean talk about business? Oh, we have lawyers who do that.’ He just had no interest in participating in a discussion of the legal ramifications of a parody of a Sgt. Pepper’s cover.”

Despite the cover-art tiff, Zappa would later enlist Ringo Starr to portray him in his 200 Motels film, and jammed with John Lennon onstage at the Fillmore East in 1971.

8. Zappa had a bad experience hosting SNL.

When Zappa hosted Saturday Night Live in October 1978, the artist’s drug-free (and outwardly anti-drug) lifestyle allegedly came into conflict with the show’s boisterous, often drug-fueled cast members.

One sketch featured Bill Murray and John Belushi as Zappa fans who “freak out” when they learn that their favorite Mothers albums were not recorded under the influence of drugs. A deadpan Zappa delivered his lines, eyes fixed on the cue cards, while the SNL cast overreacted around him.

“I thought the whole skit sucked myself, and I was stuck doing it,” Zappa says in the doc. “They wouldn’t let me write anything for the show.” Previously a musical guest in 1976, Zappa never returned to SNL following the 1978 hosting debacle.

9. Zappa blamed MTV for the decline of the record industry.

Performance art, bizarro movies (like 200 Motels), Bruce Bickford animation, and concert videos were important components of Zappa’s music, so one would think he would embrace the arrival of MTV, a network dedicated to the visual side of music. But he recognized early on that music videos would have a detrimental, homogenizing impact.

“The record industry decided this is the wave of the future, and they started signing only groups who look good, and the whole idea was making ‘picture music,’” Zappa says in the doc. “When the music business was still sort of about recording songs, you could have a hit record if it caught on in one of 10,000 different radio stations in America. Now, instead of having 10,000 chances to make a hit, you’ve got one.” (In a quote excised from the film, Zappa adds that “MTV has all the record companies by the balls.”)

10. Zappa’s biggest hit was the result of his daughter just wanting to hang out with her dad.

As the documentary shows, Zappa’s constant touring often made him an absent father. In 1982, his teenage daughter Moon Unit slid a handwritten note under his studio door — beginning “Daddy, Hi! I’m 13 years old. My name is Moon,” as shown in the doc — and asked to collaborate. The result was “Valley Girl,” the biggest and lone Top 40 hit of Zappa’s career.

11. “Zappa” was synonymous with “freedom” in Czechoslovakia.

The film opens and closes with what was Zappa’s penultimate onstage appearance with a guitar, a 1991 concert in Prague, Czechoslovakia, freshly democratized by the Velvet Revolution. “This is the first time I’ve had a reason to play my guitar in three years,” Zappa tells the audience, many of whom waited decades to see him live. “Please try and keep your country unique. Don’t change into something else.

Zappa had an unlikely influence on the architects who would lead the Velvet Revolution, including author Vaclav Havel, future President of Czechoslovakia and a noted Zappa fan. “In Czechoslovakia, when young kids played rock music, the police would tell them ‘Turn off that Frank Zappa music,’” someone states in Zappa. “And all of a sudden, here’s Frank Zappa. He was a symbol of this freedom.”

Following his 1991 concert, Havel named Zappa as Czechoslovakia’s Special Ambassador to the West on Trade, Culture, and Tourism, although the title was short-lived; U.S. Secretary of State James Baker — whose wife Susan was aligned with the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) that Zappa famously clashed with at a Washington D.C. hearing — forced the Czech government to rescind the honor.

From Rolling Stone US