DJ Screw’s fingerprints are all over mainstream music, from Travis Scott’s chart-topping Astroworld album that shot the producer-rapper’s career into the stratosphere, to Solange Knowles ode to Houston, When I Get Home, to her superstar big sister’s resurgent single “Bow Down/I Been On,” that preceded her world-stopping eponymous fifth album. This music slows and stretches vocals and beats, morphing sounds into molasses in the way Screw popularized, first in Texas, then nationally. So much music finds its origins in Screw’s style, like the “slowed + reverb” edits of popular songs littered across the web or the Chopstars “chopped not slopped” reimaginings of whole projects, like the soundtrack for 2016 Oscar winner Moonlight.

In a new book, DJ Screw: A Life in Slow Revolution, coming April 19, 2022 from the University of Texas Press, Galveston native and writer Lance Scott Walker traces Screw’s path to prominence, from his meticulous study of his mother’s records as pre-teen — when he scratched her prized ‘Ring My Bell’ record and other treasures into oblivion — to earning a diamond clad ring for his culture-making mixtapes at a prominent New York City award show less than a year before his untimely death in 2000. Weaving flashes of his own voice into an oral history featuring over 130 of Screw’s friends, family, heroes, students, and more, Walker stitches together a full picture of the iconic DJ’s legacy.

Walker’s book comes after 16 years of research and writing four other titles archiving the Houston rap scene. As he worked, other tributes to and explorations of Screw’s story have emerged, particularly in the last few years. The summer’s season of Spotify/Gimilet’s hip-hop podcast Mogul was dedicated to Screw. Last December, the Hollywood Reporter announced that Isaac Yowman and Sony were developing a full length DJ Screw biopic after Yowman premiered a shorter film that winter. Last January, Yowman teased a documentary on DJ Screw as well.

“What’s beautiful about the story of DJ Screw is there’s so many different ways to tell it,” says Walker. “I’m so excited that Houston’s got a crop of young writers that are doing great work down there: Brandon Caldwell, Shelby Stewart, Maco Faniel, Rocky Rockett, Julie Grob, and Shea Serrano’s in there because he did so much chronicling of the Houston hip-hop scene. I’m happy with how much stuff I was able to get in the book, but I’m happy that it’s not the final word.” Here, he talks about his entry to the Screw cannon and offers an exclusive first look at the cover for DJ Screw: A Life in Slow Revolution.

Your untraditional biography of DJ Screw includes dozens of voices. What’s your relationship like with these people in his orbit?

It’s different with everybody. There’s some people who I’m closer to; there’s others I’ve butted heads with a little bit. But that’s also why you take your time with something like this, because people get to know you over a long period of time; your intentions and what you’re trying to do becomes clear over time. You end up developing friendships. There’s people that I text on holidays, there’s people whose birthdays I know that I text, there’s people who call me on my birthday. I’ve been working on this book for a long time, so anybody who’s been a part of it or whose orbit I’ve crossed into, I’ve had a chance to explain it to them, I’ve had a chance for them to see some of my other work out there and to see what I’m doing and how I’m trying to highlight their voices as opposed to mine.

In the preface of the book, you mention that you’re an outsider in Screw’s life, that you’re coming into it as a white writer and that you couldn’t tell his story alone. What made you decide to take on this book?

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Nobody else was doing it. I started slowly mentioning it to a lot of people, because I wanted to kind of take the temperature — is there somebody else out there who’s writing this book? Is there a Black writer out there who’s writing this book? Even 15 years ago, it wasn’t lost on me that that’s an important part of the perspective. Over years of taking the temperature and looking around and keeping my ear to the ground, nobody was writing the book. So that’s why I started slowly working on it. And all I can really do in the end is try not to make the narrator of the book too white. That’s why I formatted it the way I did, to where most of what you’re reading is in other people’s words. I wanted to highlight the voices of the people who are around him and be somebody who’s just telling you the story around the campfire based on all the conversations he had.

What’s the most recent thing you’ve heard DJ Screw’s influence over?

There’s a song that I heard in the grocery store the other day. And it was an R&B song, and I Shazamed it and I took a screenshot because I was with my wife. I was like, “Do you hear that double tap?” She’s like, “What?” I was like, “Do you hear the double tap?” I was like, “That’s from DJ Screw right there.” [The song is VanJess’s “Feelz Right.”] And it’s not to say that nobody else has ever done it, it’s not to say that nobody else has ever done a double tap, but there’s a very specific way, much like there’s a very specific way that John Bonham or Omar Hakim played drums. There’s a very specific feel that they had on the drum kit, and there’s a very specific feel that Screw had on the turntables that no one else has ever been able to replicate.

Have you ever imagined what Screw might be making or even how other people in music might be experiencing him had he not passed away?

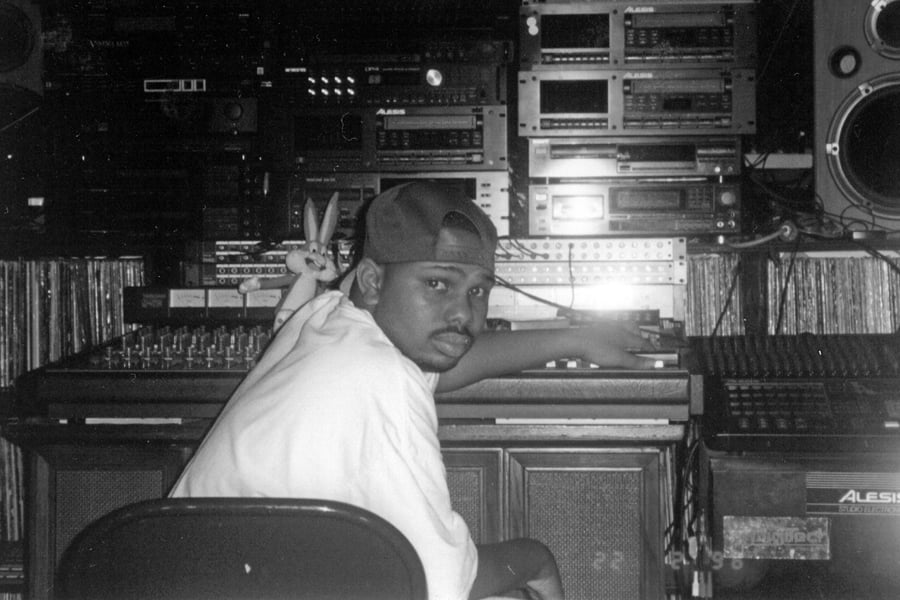

I think we’d know about a whole lot more artists that he would’ve taken under his wing. That was something that was a big part of his life. There’s maybe a lot of people who didn’t become artists just because their life took a different path, and their paths didn’t cross with DJ Screw because he wasn’t here. I think that’s maybe the most profound part of it. But we talk a lot about how he was just a vinyl and cassette guy, and that’s true, but he also did acquire gear over the years, he upgraded his gear as he got more money, he would buy more tape decks and processors and that sort of thing.

I think he probably would’ve taken on the digital era in his own way, on his own terms. Technology now is insane with how fast it moves and how much artists and musicians can do really just hitting a couple buttons. He didn’t use computers, he didn’t use any kind of digital processing. He only, as far as I know, made one recording that even went to digital tape. So I think he would’ve continued to experiment, and I think his business sense would’ve changed, maybe starting a label and just doing some different things with the resources that he already had, and using technology in a way that felt right to him.

In the book, you write “When he ran things back—to tap the drums, repeat words or whole phrases—Screw was emphasizing what he wanted to hear.” Do you hear that same intentionality from the people who are chopping up music today?

Not quite, but also, I’m not as up on contemporary stuff as I would like to be. Of course when you listen to different slowed and chopped music mixes, you’re going to hear some of that, but I think the magical thing about when you listen to DJ Screw is that you’re hearing something that he very personally is connecting with. That’s not to say that other DJs aren’t feeling that, of course they are. But this is the originator and he’s the one who took these different techniques and created this style with them, this stream of consciousness of where he wanted to take his music. You have to think about it, it’s a very different world. DJ Screw never even lived to see 9/11. He lived in a very different time than what we’re talking about. So we’re talking about different stuff, music, 1990s gangster rap — that was his wheelhouse, that’s what he was listening to. They’re talking about different stuff. So he’s running back things from his era that he’s hearing, that he’s feeling. And like I said, it’s not to say that artists don’t do that today, but there’s just no magic like the way he heard it.

From Rolling Stone US