Here’s a partial list of musicians we lost in the 2010s: Aretha Franklin, David Bowie, Chuck Berry, Ornette Coleman, B.B. King, Etta James, Whitney Houston, Lou Reed, Leonard Cohen, Prince, Merle Haggard, Kitty Wells, João Gilberto, Ravi Shankar, Tabu Ley Rochereau, David Mancuso, Amy Winehouse, Abbie Lincoln, Gil Scott Heron, George Jones, George Martin, George Michael, Allen Toussaint, Donna Summer, Phife Dawg, Prodigy, Adam Yauch, Heavy D, Captain Beefheart, Robert Hunter, Gregory Isaacs, Johnny Otis, Big Jay McNeely, Levon Helm, Kate McGarrigle, Guy Clark, Pete Seeger, Ralph Stanley, Gregg Allman, Glen Campbell, Maggie Roche, Mose Allison, Scott Walker, Jimmy Scott, Horace Silver, Fontella Bass, Lesley Gore, Percy Sledge, Alan Vega, Bernie Worrell, Wah Wah Watson, Scotty Moore, Roy Clark, Ric Ocasek, Roky Erickson, Tom Petty, Walter Becker, Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, Ray Manzarek, Glen Frey, Keith Emerson, Greg Lake, David Axelrod, Willie Mitchell, Tommy LiPuma, Ronald Shannon Jackson, Yusef Lateef, Ben E. King, Tony Joe White, Don Williams, Daevid Allen, Gilli Smyth, Jaki Liebezeit, Holger Czukay, Ray Phiri, Ray Price, Butch Trucks, Naná Vasconcelos, Troy Gentry, Mindy McReady, Rosalie Sorrels, Dolores O’Riordan, Daniel Johnston, Gord Downie, Mark Hollis, Chris Cornell, Kim Shattuck, Avicii, XXXTentacion, Lil Peep, Mac Miller, Nipsey Hussle, Neal Casal, Sharon Jones and Juice Wrld. And to be clear: this just scratches the surface.

People die every decade, but this was a shocking concentration of artists, giants of a generation or two, bedrock innovators plus younger trailblazers. Social media impacted our perception of it, magnifying mourning and loss as we all shared personal epiphanies, favorite songs, photos, video clips and other digital relics.

Art shaped our responses, too. The tradition of the death poem is plenty long, and there were many notable examples of it in the ‘10s. Advances in digital recording probably had something to do with it — home-based studios made work easier and less expensive for artists in failing health, working on erratic schedules dictated by their conditions. Not everyone gets a chance to compose their death, or wants to. But some artists who had early warning, inspiration, and strength enough made music that dealt specifically with dying: summarizing legacies, creating mementos mori, or simply consecrating their paths, doing what defined them.

Some of the most moving work came via the latter. Phife Dawg’s verses on A Tribe Called Quest’s We got it from Here… Thank You 4 Your service, recorded in his final months between three-day-a-week dialysis sessions, rang with his familiar righteous brawler uplift. On “The Space Program,” he referred to the dead strictly in third person, dispensing inspiration for the living in the interest of revolutionary wrong-righting: “For non-conformers, won’t hear the quitters/For Tyson types and Che figures/Let’s make somethin’ happen,” the man born Malik Taylor insisted, a loop from Andrew Hill’s 1969 spiritual soul-jazz gem “Lift Every Voice” buoying him with history. Phife would surely have had more to say on the solo album he’d begun, Muttymorphosis, left unfinished when he died in 2016. But he did complete “Dear Dilla,” a track memorializing his genius beat-making friend (whose LP Donuts is itself one of modern music’s great final statements). In the epistolary lyrics, Phife dreams he’s sharing a hospital room with Dilla, who’s making beats on his Akai 3000. In the song’s video, Phife struggles with his failing kidneys, gets bad news from doctors, and in a heartbreaking scene, must refuse a donut from Detroit’s Dillas Delights on account of his diabetes. “Hold tight, this ain’t the last time I see you,” Phife tells his dead friend, “Due time, that’s my word, I’mma see you.”

Gregg Allman’s career was as much about interpretations as songwriting, so it was fitting that Southern Blood was mostly a farewell mixtape of covers. Its one original, “My Only True Friend,” is the testimony of a dying artist hoping his work will grant him useful immortality. “I hope you’re haunted/By the music of my soul/When I’m gone,” Allman sings, “I can’t bear to think/This might be the end.” The covers are thematically on point: Tim Buckley’s rear-viewing “Once I Was,” Dylan’s Planet Waves sign-off “Going Going Gone,” the latter day Garcia/Hunter existential meditation “Black Muddy River,” and so on, ending with Jackson Browne’s “Song For Adam.” Browne’s reflection on the death of a friend made Allman think about his brother Duane, and during the session, when Gregg hit the line “it seems he stopped his singing in the middle of his song,” he choked up and couldn’t finish. The gap was left as is. Unable to track harmony vocals for the record after his condition worsened, he had Browne come in to sing them.

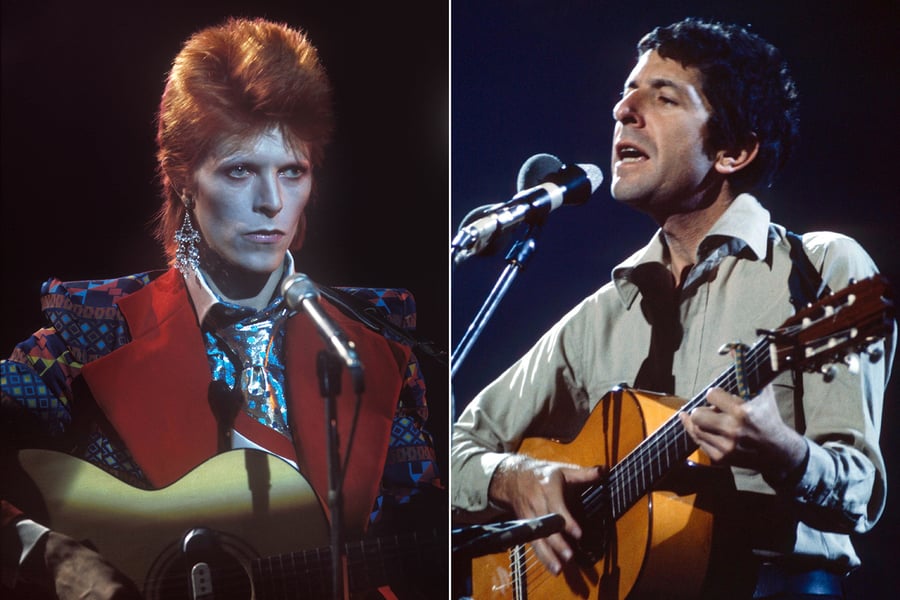

In his final months, Leonard Cohen wrote his way out of the world. With help from his son, Adam, he produced material for two separate albums, the 2016 You Want It Darker and this year’s posthumous Thanks for the Dance, plus a volume of poems and ephemera, The Flame. In them all, Cohen looked into the abyss and reflected on his past. He bid farewell to his late muse Marianne Ihlen, the subject of “So Long, Marianne” (“Traveling Light”). He enlisted the Congregation Shaar Hashomayim Synagogue Choir, engaging his Jewish-Canadian heritage (“You Want It Darker”). He conjured sexual conquests (“The Night of Santiago”), the fading of desire that comes with age (“Leaving The Table”), and the ache of deep loss (“Thanks For The Dance”). And he acquiesced to the inevitable failure that marks all life (“The Goal”).

Those records stand with Cohen’s greatest, just as Blackstar stands with Bowie’s. In what approached a culmination of legacy, Bowie recruited an entirely new band of top-flight New York City jazz players to execute some of his most complex music, working in largely uncharted territory. “Look up here, I’m in heaven,” he intoned, cheekily and tragically, in the video for “Lazarus,” laying in a hospital bed with a stylized bandage over his eyes, ranting like a deranged convalescent who literally collapses at his writing desk. He’d been simultaneously developing Lazarus, a musical that rewound his oeuvre, swirling together elements of Hunky Dory to The Man Who Fell To Earth, telling a tale of an artist at the end of the road. When Bowie died just weeks after its New York City opening, its meaning deepened, as did Blackstar‘s, an album released on his 69th birthday, two days before his death in January, 2016. Listen to that record now, with its allusions to lesions and Elvis and fame gone awry; it feels like it’s still deepening.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

At the brink of the ’20s, older artists continue to reshape their legacies. Joni Mitchell’s decision to publish her handmade 1971 art & lyric book Morning Glory On The Vine reframed some of her most well-known work, as did various tributes, including Brandi Carlile’s recent live recreation of Blue. Bob Dylan’s still reinventing his oeuvre nightly on his “Never Ending Tour,” and expanding his recorded history with the Bootleg Series — most recently, with his late-sixties sessions with Johnny Cash (whose American Songs series are their own landmarks of career final statements).

Others refine their legacies outside of the spotlight. David Jackman, the English visual artist and drone-based musician who has released over a hundred recordings during the past thirty-plus years, has just issued Herbstsonne (Autumn Sun), an album that in some ways seems to epitomize his artistic practice. A single 47-minute track — issued in a limited run of 300 CDs via the small German Die Stadt label and unavailable through streaming outlets — it’s a semi-ambient instrumental piece best experienced on a traditional sound system, one with enough bass response to give its complex, bone-rattling low-end tones full expression. It’s plenty autumnal: church bells toll for thee, the drone of an Indian tanpura conjures eternity. But the real action is the cluster-bomb piano chords that seem to drop from the sky — an unnerving but satisfying shock each time, tart and beautiful — with tones that decay like refractions of the final chord of The Beatles’ “A Day In The Life.” The elusive-per-usual maker isn’t explaining the album, let alone discussing his health or personal life. But it’s as potent as any of the aformentioned works, a sacred abstraction of musical death-rendering, handsomely minimal, both consoling and disturbing. It’s a fitting coda for a decade in which mourning, for the spiritual and for the corporeal, has become a default response.