Last year, Dawes met producer Dave Cobb at his Nashville studio. The producer — who has made hit albums with Chris Stapleton, John Prine, and more — told the California band what he thought of their sound. “He’s like, ‘You know what I think Dawes needs?’” recalls Taylor Goldsmith, the band’s lead singer and main songwriter. “‘You need a record where everyone just gets out of the way and lets the lyrics be the focal point.’ And then he started playing us tracks off of Plastic Ono Band. He just seemed to have this vision: ‘This is what I think Dawes should do. Fuck extra guitars, fuck a bunch of synths.’ He wasn’t disparaging our previous work, but it was bold. And I really appreciated it. It got us all excited.”

The result is Good Luck With Whatever, which came out in October. The album captures the band shifting away from the rich, meditative sound of 2018’s Passwords and having some fun, on the Cars-y “Who Do You Think You’re Talking To?,” about living with the ghosts of a past relationship, or the blues stomper “None of My Business,” in which Goldsmith gets into a bar fight and has a long conversation with a Father John Misty fan (“He said, ‘Is it true he doesn’t eat/But lives off staring at the sun?/Or that he keeps a monkey as a pet/And taught him how to tune his drums?’”)

The album continues a steady, prolific run that began with 2009’s North Hills. The band have been opening up their sound in various ways since, embracing Grateful Dead folk-rock jams on 2015’s All Your Favorite Bands and adding strings and synths for 2017’s We’re All Gonna Die. The new album is also full of spare, moving moments like “St. Augustine at Night,” which touches on how everyone embraces adulthood differently. It’s something Goldsmith, 35, has been thinking about. He and wife Mandy Moore (who married in 2018) recently announced they’re about to become parents. We caught up with Goldsmith about the new album, how his marriage has inspired his songwriting, and how to keep a band together after seven albums and more than a decade on the road.

Dawes has been a really hard-touring band for the last decade. What’s it been like for you to be off the road?

I mean, it sucks. I won’t lie about that. But I will say that when it all started, I felt like, “I’m gonna see sides of myself that I’ve never met,” you know? I’m gonna see how I react to circumstances that I’ve never had to experience before. And I really felt like, “Oh, wow, I pivoted.” I didn’t lose my sense of self. I didn’t recede. I scored a little short [film]. I’ve been cowriting for other people’s projects. I didn’t just, like, turn into a ball and wait ’til tour comes back. And I didn’t resent being home. On one hand, I do feel very lucky and grateful. Not only are we having this kid, but because of [Mandy’s] work kind of shutting down for a good bit, and my work shutting down … it felt like, “We’re never going to have this kind of time together again, ’til we’re two retired people.” And we really get along great. I know that sounds simple enough. So I felt in those respects, it was like, “This has been such a joy.” But I also identify with being a guy on tour. It’s what I like. It’s the one thing I know that I know how to do. And so I miss it desperately, especially with putting out a record and wanting to spread the good word.

You’ve really stepped up your lyrics on this album. It really feels like you’re having a conversation with the listener. Is that something that you have to work on? Does it come naturally, or do you have to learn not to be heavy-handed?

Before we were Dawes, we were called Simon Dawes. At that time, I didn’t know what life was. I didn’t have experiences. I was, like, 17 or 18 years old. And so as a lyricist, it was like a lot of mimicry. I had to experiment to understand what feels false, and feels like bullshit for me. It doesn’t sound like bullshit when it’s, you know, “Tombstone Blues” by Bob Dylan. That feels like truth. That feels like conviction. And I feel like, if there’s moments where I might dabble in a more impressionistic approach, even on this album on a song like “Good Luck With Whatever” …. to me, it’s a song about relinquishing your codependency, hence the chorus and the title. But it’s also a song about the manifestations of paranoia. And it’s not a narrative song, that’s for sure. It’s not like some stream of consciousness poetry that’s inaccessible. I guess as I got older, [it’s been] getting away from Simon Dawes and figuring out what turned me on as a human being. You reach for stuff, you start to see what suits you what doesn’t. I would pick up an F. Scott Fitzgerald book and feel like, “Wow, this is fucking me up. This is getting me.” And then I would reach for, like, T.S. Eliot, and I just don’t think I’m smart enough. As time went on, I kept drifting towards these novels and narrative writers. That’s why a guy like Warren Zevon is maybe my favorite lyricist, because it’s always smart. He’s going for complicated ideas. He’s creating complicated reactions from a listener. But you never are misunderstanding what he’s getting after.

What new songs did you find yourself breaking new ground on?

I think it was hard for me to write certain songs because I was scared of … I hope this doesn’t make me sound like an asshole, but a song like “St. Augustine at Night” – I was just thinking, “this is really kind of plainly-spoken. And the progression is pretty straight.” We just don’t do the same kind of chordal structure or lyrical winks that other Dawes songs have. It doesn’t really play with structure that much. I think it took me a minute to allow that for myself. Not that I’m better than that. It was a matter of me being like, “I’m gonna trust that this is good because it feels right.” Also, “Didn’t Fix Me” is a five-verse song. Part of me was like, “Can I make this work?”

As a songwriter, when you listen to those Dylan songs that are like five, six, seven verses — “Visions of Johanna,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Desolation Row” — to me, part of why that it functions, is the way Dylan carves out a melody, the way he embellishes the melody as the song goes on, the space he puts in between each verse. How much space, how it differs from the break before, when there’s a harmonica break, when there’s not; these little tiny, tiny things. It’s almost like you’re testing the foundation of a house. Because you keep wanting to add another floor, and I feel like with “Didn’t Fix Me,” it’s like, “If this song isn’t good enough, it won’t be able to handle a fourth and fifth verse.” And I don’t mean that arrogantly, but it was just an experiment. I had never done that before. That was some new territory for me.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

I think the thing for me is being cognizant of how to pace our records. I think, if you go back to North Hills, it’s pretty darn serious and sad the whole way through. And I remember once Johnny Fritz told me when we I think we’d just released Stories Don’t End or something. He was like, “Man, you are one of the happiest guys I know. And you would never be able to tell that from your music.” I took it to heart. And I felt like, “I’m not that cool with that.” I want these songs to represent a full human picture.

And it’s true. I’m happy to say this. I’m one of the happiest people I know. I feel very lucky. I don’t feel like I did anything right to deserve that. I want the music to represent that, and I also noticed that with all of my favorite records, they do this incredible job of when to punch you in the gut, when to go light, and all these songs frame each other. One example I use is a record like Beggars Banquet. Like, if everything was as dense as “Street Fighting Man” and “Sympathy for the Devil,” I probably wouldn’t love it as much, even though those are my favorite songs. And I feel like it requires songs like “Dear Doctor” to prime you for “Street Fighting Man.” Let it Bleed, same thing, “Country Honk” makes you ready for “Live With Me.” Even songs like “Who Do You Think You’re Talking To,” I don’t know if I would have put those songs on North Hills, and I wish I had those songs back then.

What’s the story behind the album title, Good Luck With Whatever?

I love it when people say it back to me. It almost says more about them because they interpret it their own way. I like that it has this interpretable quality that some people read it and laugh, because it feels so dismissive to them. And other people feel like it’s another way of saying “May All Your Favorite Bands Stay Together,” a really sweet way to just say like, “I am not going to pay close attention, but whatever you end up doing. Good luck with that.” So some people see it as really sweet, and some people see it as really cynical.

What it means for me, I think a lot of this record is about relinquishing my codependence. To recognize when something doesn’t concern me. Like “Between the Zero and the One,” they’re fine. They’re not just like everybody else. Don’t judge these people too harshly. We’re all in the same place at different moments in our lives. And then more explicitly with titles like “Good Luck With Whatever,” I’m not going to judge, I’m not going to have an opinion where I’m not asked to. But I like recognizing that the world is a little less black and white. This sort of self-acceptance, for better or worse — rather than, like, insisting that I changed — I felt like it all filtered into that title, if that makes any sense.

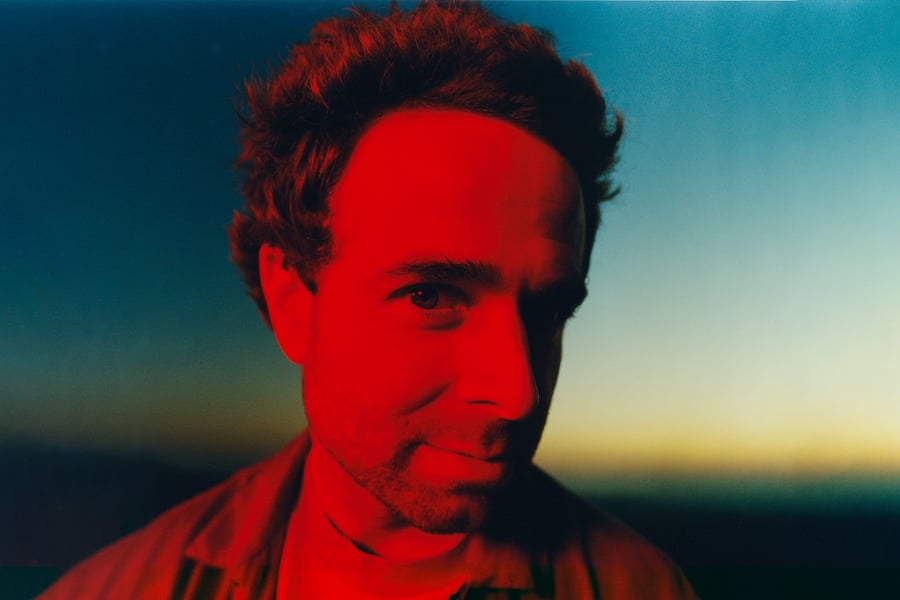

Jacob Blickenstaff*

I can hear that in “Who Do You Think You’re Talking To?” Did anything in real life inspire that song?

Yeah, totally. The seeds of it were were started a long time ago, but I wasn’t finished ’til this record. This wasn’t something that my wife and I were navigating anymore, but there was a time in our lives where, you know, she was still dealing with a divorce, and I was in her life. It’s that thing that everybody has their own version of…something triggering her, whether it’s a memory or word or a place. Like, “Oh, let’s eat there,” and all of a sudden, it’s a reaction you did not expect. I wanted to ask that actual question [“Who Do You Think You’re Talking To?”] and put it into a song about being able to recognize that we all have histories of our own, and that we all have to process them. Ironically, we don’t process them, typically, with the one who caused the drama. We process it with the next person who isn’t responsible for the drama, hence why you’re together.

So for me, it’s like, how do I refrain from my selfish tendencies and stop taking it personally? How do I still be there for someone that needs to go through something, even though my ego wants to to tell me, “I don’t deserve this, and she’s taking it out on me, which is bullshit.” And again, that was from a long time ago, and I embellish for the sake of a song. I didn’t have a song about that. I guess it’s a thing that we all experienced, but I didn’t know if there were that many songs about it, I guess.

Another highlight of the album is “Still Feel Like a Kid.” I’ve read musicians say that being a rock star allows them to never grow up. Do you in some ways still feel like a kid? Does that make it hard to relate to people around you?

I think for me, it’s been a matter of gratitude and just, like, celebrating. I think there was a part of me that wanted to turn it into shame in a way, because I’d come home and having old friends, as they go through life, we’d all get together and there’d be these conversations where my brain was like, “Wow, this thing’s pretty adult. I can’t believe they know what they’re talking about. Because I don’t know what they’re talking about.”

It’s this feeling of like, did I fuck up? Did I pursue this like 17-year-old hobby at the expense of adulthood? And in some ways, the answer is yes. But I think it’s in the good ways. I am prouder than ever that what I do for a living is yell my head off, and pace a stage at full speed, and play guitar solos and nerd out. I think I was nervous, like, “Oh, man, am I not a mature human?” And I think, “No, I am.” I show up in the ways I need to, when I need to, but when I’m on tour, when I’m writing a song, I actually am nurturing the 15-year-old in me. And that’s what makes me feel luckier than anything with being a musician. I was tempted to resent it. I think when you find something that helps you hold on to that part of you, and keeps it alive … We’re some of the luckiest people in the world. And sure, I don’t really know how to talk about finances or real estate. But I’m cool with that.

“The bands that are still together, still killing it,” says Goldsmith, “they prioritize the band over everything.”

Dawes has been together for more than 12 years now. Is it hard to keep a band together this long?

I think the intense work that we had to do was probably early, when we were still learning how to do it. Simon Dawes broke up, and a lot of that was just my inability to communicate with other people. That would manifest in bad ways. So going through that, and then seeing other bands, hearing about other bands that do exist for the long haul, you start to learn the same lesson over and over again: The bands that are still together, still killing it, they prioritize the band over everything. Not their private lives. But over a record, over a producer, over a song, over a show, or a tour, it’s like, “No, our feelings about this matter most.” And we’ve always been that way. Some people say they have a democratic aspect to their band. We do and we don’t. No one’s ever telling anyone else what to do. No one’s ever railroading anybody else. And we prioritize each other.

Every band is different. We hear these stories about, like, the Chili Peppers or the Stones — they don’t start writing until they’re together. They all get together and Keith will make up a riff and Mick will start making up melodies and they come up with the songs that way. Same with the Chili Peppers, they do it together. Our band’s DNA is a little different, where I write the songs by myself, almost like a singer-songwriter. But it’s very important that we’re a band. We’re very proud of that. We don’t want our records to sound like we’re a singer-songwriter. We don’t want to be perceived like that. These records are Wylie and Lee’s and Griffin’s as much as they’re mine. So when we go into the studio, it’s very important to me to release these songs as much as I possibly can. I show them what I wrote, and then we figure out how to play them together. And sometimes that might result in the song not making a record, because someone wanted to do a wacky thing, but that doesn’t really actually happen. But what does happen frequently is I get surprised, and that’s so fun.

I always felt like I’m a relatively nice person, but yeah, when I was 20 years old, I was terrified. I was insecure. I was in a band with Blake Mills, who’s like my hero. When Blake’s like, “I’m a great singer too,” I think there was a part of me that would just be like, “Oh God, this threatens my identity.” And that would come out in ways I’m not proud of, like, why [can’t] I sing it? Even though it was all ego. It’s just stuff I did wrong that I wouldn’t do again because I think I have a better sense of myself. So I try to take that those lessons into this band.

From Rolling Stone US