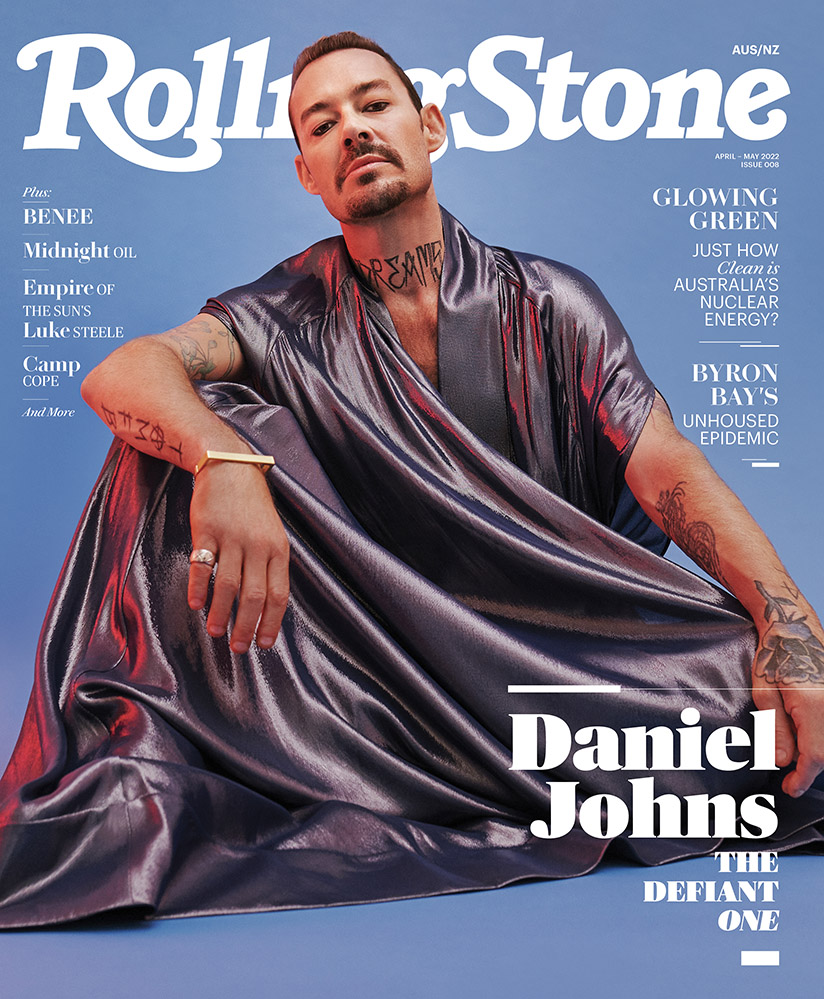

Sam Wong and Long Story Short for Rolling Stone Australia/NZ

As Daniel Johns releases his first solo album since 2015, he's clearing the air about his past and present, and plunging headfirst into his 'FutureNever'.

“In Australia, I’m kind of famous, so I kind of expected something,” Daniel Johns says with a sly smile. “I assumed something would happen, but I didn’t expect the round of applause I got.”

It was in the final months of 2021 that the world found itself engrossed in the latest Spotify original podcast, designed to answer its titular question, Who is Daniel Johns?. The multi-part production was an impressive undertaking, with host Kaitlyn Sawrey diving deep into the life of its namesake as he eschewed his usual apprehension toward media attention in an attempt to invite fans deeper into his world.

As with anything Johns touches, it was a riveting success, beating out the likes of Joe Rogan to become Australia’s most popular podcast, with countless listeners globally receiving an unprecedented insight into one of the country’s most beloved artists. But as the dust settled, one question remained: if this podcast told us all about Johns’ past and present, what does the future hold?

Daniel Johns, photographed in Newcastle on February 12th, 2022, by Sam Wong and Long Story Short.

It’s a cool day in Newcastle as Daniel Johns welcomes me into his coastal home; the same home he once referred to as a “‘Seventies porn palace” out of Boogie Nights. A brewing rainstorm can be seen in the distance via an ocean view, while a friendly hug from a barefoot Johns accompanies the trip across the threshold and into a world that can only be described as an artist’s paradise.

Guitars, vintage synths, old drums, and countless other pieces of gear sit to one side, while renovations see a number of paintings (Johns’ lockdown-inspired foray into the medium) scattered against a wall. Just by the door sits a Yamaha grand piano, the same instrument on which Johns wrote the material for 2002’s chart-topping album, Diorama.

On paper, the prospect of sitting down with Johns is an almost daunting task. After all, he’s a 42-year-old with the legacy of an 80-year-old, he’s sold more than ten million records worldwide for his work as a member of Silverchair, The Dissociatives, DREAMS, and as a solo musician, he’s won more ARIA and APRA Awards than any other artist (21 and six, respectively), he’s the only Australian to win both a Grammy and an Emmy in the same year, and his disdain for both interviews and being in the spotlight is well-documented. But as we sit down in Johns’ living room, his dog Gia sitting casually alongside us, the perceived barrier crumbles. He asserts himself not as an icon of the music world, but rather, a vulnerable human being with an innate desire to create.

“Some people write records so they can perform it live, which is completely cool, but I don’t write music so I can perform it,” Johns explains, his sleeveless black top showing off his famous tattoos. “I write music because I’m trying to figure out ways to get the shapes in my head into a sonic form. I don’t think I’ll ever stop because I don’t think I’ll ever get what I want.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“I write music because I’m trying to figure out ways to get the shapes in my head into a sonic form. I don’t think I’ll ever stop because I don’t think I’ll ever get what I want.”

The podcast Who is Daniel Johns? arrived in October of 2021, more than six years after Johns had last released a solo album by way of his 2015 solo debut, Talk, and three years since the release of No One Defeats Us, the long-awaited debut from DREAMS, a collaboration with longtime friend and collaborator Luke Steele.

“I believe that the embryo of the podcast was me saying to the record company, ‘There has to be a way to reach people with music where I don’t have to perform on stage’,” he recalls. “Because I really, really don’t want to do that.”

Immediately, the podcast became a massive hit, with fans the world over appreciating the invitation into Johns’ rise to fame as the frontman for Silverchair while still a teenager, his vulnerability as he discussed his battles with both anorexia and reactive arthritis, and the bluntness with which he clarified that not only would his iconic band never reunite, but he would also likely never perform live again.

“I didn’t really comprehend that, for lack of a better term—and I hate this term—my ‘fanbase’ was still there, that they’re still hanging around,” he explains. “I think that’s the beauty of being in the game for almost 30 years; I think I’ve proven that I don’t deliver shit.”

“I think that’s the beauty of being in the game for almost 30 years; I think I’ve proven that I don’t deliver shit.”

Despite describing the podcast as a way to escape a need for more therapy, Johns explains he didn’t expect anyone to care too deeply about it, but was honoured that listeners were eager to hear the truth after years of misinformation, which included a high-profile defamation suit against News Corp in 2019. That case resulted in Johns receiving a six-figure settlement after the publication of photos which falsely claimed to show Johns “swaggering out of [a] notorious Sydney brothel”.

Using it as an opportunity to set the record straight on many questions that would frequently come his way, Johns admits it has the added benefit of helping listeners with their own struggles.

“There’s a lot of people that have issues that they’re embarrassed to talk about. It’s not embarrassing to have been sick or fragile or to be sad,” he notes, before his mischievous smile gives way to a sly quip. “No one’s embarrassed about being happy, except for goths.”

However, the biggest benefit of the podcast was the way it managed to serve as a bridge between the past and the future—a necessary step which allowed Johns to excise any mental confusion and forge ahead with pure clarity.

It was in early December that Johns announced the forthcoming arrival of FutureNever. Some snippets of his second solo record had been teased throughout the podcast, but it wasn’t officially unveiled until Johns shared a personal letter to his fans.

“FutureNever is a place where your past, present, and future collide,” he explained. “In the FutureNever the quantum of your past experiences become your superpower.”

“I know I have a tendency to go missing but I’m back now,” he concluded. “Follow me into FutureNever.”

Preceded by no singles, the record was born out of Johns’ desire to simply “fuck shit up” and to create things that are “real and resonant”, though he admits that its almost “schizophrenic” nature will polarise some listeners.

“I’m sure I’m going to get slayed in the press, because it doesn’t sound cohesive,” he admits, casually brushing off memories of past criticisms. “But I’m not cohesive.

“Some people are going to be perplexed because it’s not an experience of a record that I’ve ever done before. It’s more a collection of stuff that I’ve been doing while everyone thought I was dormant.”

“I’m sure I’m going to get slayed in the press, because it doesn’t sound cohesive. But I’m not cohesive.”

Enthusiastically referring to it as the best record he’s made to date (while freely admitting any artist would label their current work as such), FutureNever doesn’t have origins in the conventional compositional sense of writing for the purpose of a new record. Rather, Johns explains it was the product of three entirely different albums colliding.

Never one to stop writing or composing (he admits to having thousands of demos around the place), three separate records (which will remain unheard) had managed to make themselves apparent over the years. One, dubbed “The Modern Punk Record”, featured an electronic punk sound; another—”The Opera Record”—was self-explanatory; while “The Modern Electronica Record” featured the sort of futuristic R&B sound he had ventured into with 2015’s Talk.

“I thought they were all separate records, so I was like, ‘I don’t know what the fuck to do’,” he admits, “and I also had thousands and thousands of demos.

“So I actually called my label and just went, ‘Once again I’ve bitten off more than I can chew. I don’t know what the order is, I don’t know what the fuck to do.’ And it took ages to figure out that all of those sessions which I thought were different projects, were just me doing songwriting sessions. So I was actually doing the same record.”

“It took ages to figure out that all of those sessions which I thought were different projects, were just me doing songwriting sessions. So I was actually doing the same record.”

Though initially he’d toyed with the notion of releasing the three records under different names (to which he was told, “that is the dumbest idea you’ve ever had”), Johns began to realise he had effectively created the same record three times with different genres across eight years.

Intriguingly, the genre-hopping style of the record also influenced his synesthesia–a sensory phenomenon in which one sense often involuntarily stimulates another. While many artists see colours when they listen to music, Johns’ new record reacts with his synesthesia to provoke chaotic images of gangster movies and the Forties.

“It’s crazy how many different genres there are, but it sounds like the same record,” he explains, perking up as he animatedly lists examples of famous albums that have done the same. “‘Have you heard Smile by The Beach Boys? Have you heard anything that OutKast has done?’ Most of my favourite records feel chaotic.

“I’ll do like an old school Prince funk jam, then do something like it’s from an opera, and something like it’s from the Tron soundtrack if it’s cool and it makes sense lyrically. Everything’s supposed to sound like it’s a collage rather than a painting. It’s bits and pieces stuck on each other, and it’s supposed to be a bit more dimensional.”

For many of those close to him, the creation of such a record would be of no surprise. Having long been described as a visionary, Johns’ musical ideas began to flourish as he left his teen years. Following Silverchair’s grunge-laden 1995 debut Frogstomp and 1997’s Freak Show, Johns began to showcase his unique flavour and grandiose ideas on 1999’s Neon Ballroom, an album that kicked off a run of what he labels “predominantly solo records with a great rhythm section”.

Noting that every Silverchair album was set to be the last after Neon Ballroom, Johns explains he began to perceive resentment following the creation of this record. “It was always like, ‘It’s the three of us or it’s not a thing’,” he recalls, remembering a meeting with bandmates Ben Gillies and Chris Joannou which saw him request their presence as he followed his vision.

“It was like, ‘I know this is going to be uncomfortable, but I’m going to pretty much make solo albums, and you’re going to be the rhythm section. Otherwise I’ll get another rhythm section’,“ he notes. “Obviously I would’ve preferred what [ended up happening], because they were really good, and we were all friends from childhood.”

“We were successful enough, I didn’t want to do something amazing or else I’d get murdered.”

However, the decision to work on a record such as Neon Ballroom, that is, one with a far more resplendent vision than the likes of Freak Show, was difficult for Johns, given that he had previously tried to keep his head down while in high school for fear of his aspirations making him the target of bullying.

“High school was so traumatic for me,” he recalls. “I wouldn’t say I was visionless, but I didn’t know what to do next, because if I did something too good, I was probably going to get beaten up. We were successful enough, I didn’t want to do something amazing or else I’d get murdered.

“As soon as I left high school, that’s when I moved into the house. I started writing Neon Ballroom, and then I was like, ‘Okay, everything’s changed now.'”

He pauses for a brief moment as he reflects on that time in his life, the air in the room changes and he wipes his eyes.

In 2002, Silverchair released Diorama, a record often considered to be their magnum opus. Working with composer Van Dyke Parks, and inspired by a sound more characteristic of the baroque pop genre, Diorama was a kaleidoscopic mix of sounds that went from the band’s classic grunge to an orchestral power ballad in moments. Despite lacklustre critical reviews, the record would win five of the seven ARIA Awards it was nominated for, with the band’s performance of “The Greatest View” at the ceremony considered a career highlight, especially given Johns’ battle with reactive arthritis at the time.

Grammy Award-winning producer David Bottrill, who has worked alongside icons such as Peter Gabriel, King Crimson, Tool, and Muse—and co-produced Diorama alongside Johns—recalls the sort of vision the Silverchair frontman brought to the table.

“I think he’s one of the rare talents of musical compositional ability in that he’s almost too clever and almost too talented in a way,” Bottrill explains. “I think he has a hard time tempering what he does for commercial appeal. Because I think he’s so uniquely talented as a writer and as an artist.”

One of the record’s standout moments, the five-and-a-half minute “Tuna in The Brine”, is remembered by Bottrill as an example of Johns’ legendary creativity thanks to its sweeping orchestral arrangements, complex chord structures, and soaring, almost operatic vocals.

“He’d never played piano before,” he begins, “But he got this piano, learned how to play it and wrote ‘Tuna in The Brine’. It’s an extraordinarily complex composition. I mean, nobody does that. When you’re a kid, you pick up a guitar and you write C, D, G songs—you don’t write ‘Tuna’.”

“He got this piano, learned how to play it and wrote ‘Tuna in The Brine’. It’s an extraordinarily complex composition. I mean, nobody does that. When you’re a kid, you pick up a guitar and you write C, D, G songs—you don’t write ‘Tuna’.”

Recalling the time spent working alongside Johns and his Silverchair bandmates while recording Diorama, Bottrill explains that Johns stands tall as a unique talent whose desire to create is only handicapped by the general public’s ability to understand it.

“[If] you keep driving forward and compositionally writing things that you want to develop into something special, unique, and emotional […] then you end up with somebody like Daniel who creates these amazing things,” Bottrill notes. “And sometimes—for lack of a better description—goes above or beyond what people can comprehend.”

Though he admits his only failing on the record was his inability to help Johns “dumb it down” for the masses, he concedes that some of the greatest songs in rock music were often far from the traditional compositional structure, yet received widespread praise years down the line.

“[Queen’s] ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ is a classic example of that,” he points out. “Who would say that was a structure that was pop standard format? And yet, [it was] hugely successful. To this day, it’s one of the most classic rock and pop songs ever.

“The world was open for this kind of experimentation in pop or rock music. So I was excited to explore these new, or even old dimensions, but bring them into a new era.”

One notable fan of Silverchair and the wider catalogue of Johns’ is Ryan Tedder, a prolific songwriter, three-time Grammy Award winner, and the lead vocalist of chart-topping pop/rock outfit OneRepublic. Just two months younger than Johns, Tedder explains he found himself looking to the Aussie musician as an example of what a potential career could be.

“It was like [Silverchair were] teenage superheroes because nobody, no 15-year-old that I was friends with, had even a snowball’s chance in hell of getting a record deal, much less writing a decent song,” he remembers.

“I had just started writing songs at 15. So for me, I was probably the biggest Silverchair fan in the state of Oklahoma. And then I ended up following them all the way through.”

As Tedder recalls, the careers of both Silverchair and OneRepublic were akin to passing ships in the night, with Young Modern arriving just months before OneRepublic’s debut album, Dreaming Out Loud, was released into the world. Despite this, he remembers the record and its lead single, “Straight Lines”, having a profound impact on the music his band would make.

“I remember doing promo in America in 2007 and 2008, when they were promoting [the single] and I was telling radio programmers in America, ‘Guys, you’re sleeping on the Silverchair single,” he recalls. “‘You got to be playing “Straight Lines”. This song is an absolute banger’.

“I remember that we were all so obsessed with that record. We actually have probably tried to copy it a few times with OneRepublic.”

“I remember that we were all so obsessed with that record. We actually have probably tried to copy it a few times with OneRepublic.”

But despite Silverchair’s lack of success in the US, Tedder claims it was in fact Johns’ musical versatility, and his lack of desire to pander to audiences by repeating the same trick over and over again that contributed to his overall success as an artist. While Tedder notes that Americans are notoriously the “most fickle audience in the world”, Johns’ refusal to “play the game” set up by major record labels, and to instead stay true to his own creative visions, is a testament to his status as an artist.

“Doing [The Dissociatives and Young Modern] back to back really shows the breadth and depth of what that guy’s capable of, which is just crazy,” he explains. “And then he did the solo [material], which is more R&B and urban. I think the guy can do whatever genre he wants to.

“More than anything, it’s really hard when you don’t have parameters. When you’re capable of actually genre-hopping or shape-shifting into so many genres, that is the hardest. Believe it or not, options can spell disaster, and I often end up jealous of artists who can only sing one way, really only play one instrument, and are only interested in one genre. That’s kind of a blessing, because if you’re a guy like Daniel, you’re just going, ‘Well, my option is everything’. And that’ll drive a person crazy.”

In the years following Diorama, Johns again showcased his appetite for a grander vision. While 2004 brought with it the self-titled album from The Dissociatives—a collaboration with longtime friend Paul Mac—2007 saw the release of Silverchair’s Young Modern, their final record before their 2011 split. While 2015 featured the release of Talk, 2018 saw Johns and Luke Steele release DREAMS’ first album, a record that arrived after the duo had made their live debut at Coachella—the first band to perform at the iconic Californian festival before releasing any music.

“I love that record,” Johns says of DREAMS’ debut. “I think that’s—in my entire career—the least successful and most proud I’d been of a record until now. I’m proud of all my records, but just in terms of the amount of effort, the amount of vision that went into it, and the risks that we took. I was so proud of it.”

However, it was his solo debut, Talk, that achieved the most attention upon its release. Ending a lengthy drought of records from Johns, it was—like every record he had released previously—designed as the next step in a continual musical evolution, and most importantly, a reaction to everything that had come before.

“It’s about deleting yourself and starting again,” Johns told triple j’s Richard Kingsmill at the time. In hindsight though, he argues that summation was more pertinent for FutureNever than Talk.

“Talk was pressing restart; like starting a new career,” he explains. “And it was very much on purpose so I didn’t sound like a rock’n’roll band.

“Talk was pressing restart; like starting a new career. And it was very much on purpose so I didn’t sound like a rock’n’roll band.

“FutureNever is a lot different because I’m embracing the past, I’m embracing the present, and I’m looking forward to the future. Whereas Talk was more like a desperate attempt to get to the future; leap-frogging everything that’s happened.”

Such a decision to rapidly race to the future was understandable. After all, with countless fans ignoring the prospect of a burgeoning solo career to instead plead for the return of Silverchair (whose final three records Johns looks at as solo releases anyway), it makes sense that there would be a mad dash to move ahead and break new ground.

“Talk was a protest against everyone that wanted me to keep doing Silverchair, despite the fact that Silverchair was always different,” he explains. “I was really worried about if I had a future outside of the brand and the band Silverchair. FutureNever is way more emotionally evolved.

“It’s not just about avoiding what happened in the past. FutureNever includes everything,” he adds. “The record is a celebration of self-acceptance, whereas Talk was an avoidance of myself.”

Indeed, FutureNever is an album unlike anything Daniel Johns’ fans have ever heard before. Those seeking something of a Silverchair throwback are advised to look elsewhere, but for anyone hoping to find Johns at his creative peak, it’s manna from heaven.

Due to its somewhat unexpected composition as the best tracks from three separate records, it shows an unfiltered artist at his best, and one creating work far from the idea of monetisation and commercialism.

“We started working on a record here [during lockdown in 2020] and I deliberately said, ‘This is not for public consumption; this is just for a visceral experience’,” he recalls. “I really just wanted to sit and fuck with gear and just be crazy and make shit—no one needed to hear it. But as usual everyone goes, ‘That should be the first single’.”

Frustrated by the way everything turns into a corporate exercise when you’re a signed artist, Johns turned his attention to painting—for the first time since high school—as a way to escape the idea of selling a product, even though demand for his paintings have begun to grow. Given the current mid-pandemic climate for artists, Johns is in an enviable position. He says he’s not in it for the financial side of things, admitting he’s happy with the position that he finds himself in, and that if “everything went to shit right now”, he wouldn’t care.

“I don’t think people realise how much I don’t give a fuck about that bit,” he explains. “It’s the only reason that the FutureNever is so important to me, because I’m actually so proud of it and I want people to hear it. I really genuinely do.”

“I really just wanted to sit and fuck with gear and just be crazy and make shit—no one needed to hear it. But as usual everyone goes, ‘That should be the first single’.”

It’s easy to see why. Despite its varied sounds, it feels indelibly stamped with Johns’ classic influence. A natural evolution from his last body of work, it effortlessly moves between the woozy pop of songs such as “Mansions”, the operatic grandeur of “Reclaim” (which shows a side of his work that we’ve not yet seen), and “Electric”, which feels like the closest Johns has ever come to making a ‘pop’ record. In the case of the latter, it also sees Johns working with the extremely talented vocalist Moxie Raia who, by design, remained a complete unknown to him at first.

“I’ve never met her,” he admits. “We had the song and our producer was working on the demo, and he sent it back with this funk jam in the middle with this girl. I’ve still never met her, I don’t even know her name, but I was like, ‘This chick is fire’. She sounds like a star.

“I kind of loved that I heard it back and I deliberately have never tried to figure out who it is, because even to me that’s mysterious. This random goddess comes into the song.”

Though they’ve since formally connected, that’s not the only collaboration featured on the record, with names such as What So Not, Van Dyke Parks, and Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker making appearances, while the Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan and Jimmy Chamberlin both appear on one song.

Meanwhile, the record also boasts some call-backs to Johns’ past, by way of the purplegirl-featuring “FreakNever”, which revisits his 1997 single, “Freak”, through a modernised yet childlike lens, or “Those Thieving Birds Part 3”, which completes a trilogy first explored on 2007’s Young Modern. However, one of the record’s biggest moments comes by way of “Cocaine Killer”, a song created with Peking Duk, hours after they’d abandoned what Johns believes could’ve been a huge single.

“I wrote that song right here with Peking Duk, ages ago,” he recalls. “I’m gonna say 2017 or 2018, maybe even earlier. They’re writing all these party bangers, and they played me that beat and I was like, ‘I want to do something on that’.

“Ironically it was the morning after we wrote a song that we thought was going to be a massive Peking Duk hit, and I was like, ‘Nah’. We did it in about three hours and then obviously we worked on it for ages.”

While FutureNever undoubtedly creates new opportunities, they won’t be explored in a live setting. Johns explains he no longer has a desire to perform live.

“I’m 95% sure that it’s never again,” he explains. “I never said ‘No, never again’, because it’s not healthy; you’ve said it and now you can’t. It’s like putting yourself in jail. But I have absolutely no fucking way to think in my head that that’s something I would want to do.

“I didn’t enjoy it since I was like 17. At the start, when I was like 13 to about [1997], I loved it. I just loved it because you just want to play and put pedals on. From about the second album, I’ve never wanted to be onstage. I’ll do it, for example, when Van Dyke Parks calls me and asks if you want to learn 30 American classics and play at the Adelaide Festival, I’m like, ‘it’s Van Dyke Parks, okay’. But I don’t need that validation.”

In the Who is Daniel Johns? podcast, Johns explained his mental health plays a role in his decision not to play live, with a mental cloudiness and stage fright working against him in addition to regular anxieties that go along with any performance. Stage fright might not be an uncommon experience, with a 2016 survey finding that about 75% of artists admitted to performance-related anxiety, but for Johns, it’s a debilitating condition that hampers his ability to perform to the level he strives for.

But in addition to that, he also notes that for any artist that experiments sonically, the live experience usually ends up somewhat more disappointing than the record.

“The future is freedom. That’s how I think about it.”

Though Johns has performed live in recent years—including the aforementioned Van Dyke Parks performance, two Opera House shows supporting Talk, performing with DREAMS at Coachella, and appearing alongside close friend What So Not in 2019 for a rendition of “Freak” at Splendour in The Grass—he explains that the only time he would perform again would be to aid a friend, before upping his level of certainty to 99.9%.

“I just don’t feel like a performing artist. I don’t feel like a touring artist,” he explains. “I feel like someone who needs to come up with stuff, and come up with new shit.

“The performance is fine; I’m totally cool to perform. It’s the bit leading up to it. It drives me mental. It drives me crazy, I get so anxious. If someone said to me—like they did with the Van Dyke Park Adelaide performance—’Okay, in three months, you’re going to do this thing’. I was like, ‘Okay, cool that seems far enough away’. From that night on, I couldn’t sleep. Three months of thinking about, and it drives me fucking crazy.”

Sitting in his Newcastle home, it feels as though we’ve come full circle. Johns is no longer running from or reacting to his past, and he feels at peace with the present while looking into the FutureNever. But the question remains: What does the future look like for Daniel Johns?

“That’s a good fucking question.” He looks to his right, staring through his stereo setup and casually-placed musical equipment as he pauses for a few moments to think. “The future is freedom. That’s how I think about it.”

(Cover photograph by Sam Wong for Rolling Stone Australia/NZ, with assistance by Steven.K.W.Chan, and production by Long Story Short. Styling by Jana Bartolo, and assisted by Kirsten Humphreys. Grooming by Gavin Anesbury and assisted by Lucy Jackson. Lurex cape by Common Hours. Ring by Chanel. Bracelet by Valentino.)

This interview features in the March 2022 issue of Rolling Stone Australia. If you’re eager to get your hands on it, then now is the time to sign up for a subscription.

Whether you’re a fan of music, you’re a supporter of the local music scene, or you enjoy the thrill of print and long form journalism, then Rolling Stone Australia is exactly what you need. Click the link below for more information regarding a magazine subscription.