Since nostalgia for any era begins about two decades after the fact, early-2000s look-backs have arrived right on schedule. Jennifer Lopez and Shakira’s Super Bowl takeover returned us to their end-of-the-century breakouts; Bernie Sanders couldn’t have picked a more circa-2001 rock band for a rally than the Strokes; Jessica Simpson, once a national punchline after her Chicken of the Sea confusion, has a memoir at the top of the New York Times bestseller list; and suddenly everyone is re-examining Mandy Moore’s pre–This Is Us pop career. All that’s needed now are retro Napster T-shirts.

In keeping with the new wave of 2000s longing, it’s time to look back 16 years, to the day when one of the most notorious but ingenious albums in pop history was made available online for free. Especially now that copyright law weighs heavily on the minds of so many in the music business, Danger Mouse’s The Grey Album feels like the type of project that only could have happened then — and may never take place again.

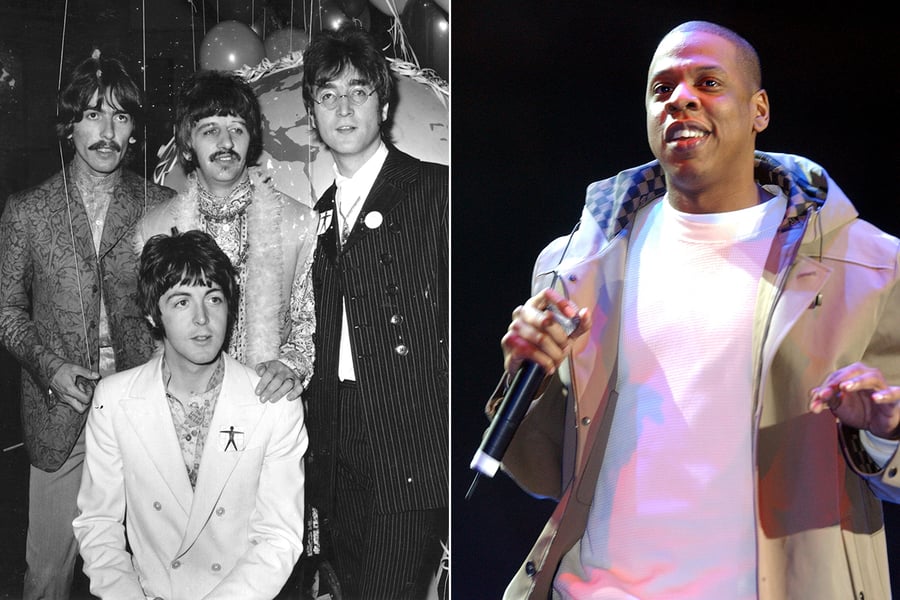

In the thriving, post-Napster world of online music, mash-ups were never as ubiquitous as they were in 2004. Most were novelties that have already been forgotten — remember “A Stroke of Genie-us,” which laid Christina Aguilera’s vocal from “Genie in a Bottle” atop the Strokes’ “Hard to Explain”? — but The Grey Album was a different, more ambitious, and more audacious undertaking. Then in his mid-twenties and striving to make his mark as a producer, remixer and DJ, Danger Mouse, a.k.a. Brian Burton, had an inspired idea: combine Jay-Z’s isolated rhymes from The Black Album (which had already been released as a separate record called Acappella) with vocal and musical parts from the Beatles’ White Album. It would be the ultimate mash-up, accelerated by advances in technology.

After piecing the album together in his bedroom studio in a few short weeks, Burton pressed up 3,000 CDs. He called his computer files “The Black-White Album,” so naturally the record came to be known as The Grey Album.

By the dawn of this century, the Wild West days of sampling were pretty much over, thanks to landmark cases like the Turtles suing De La Soul for the unauthorized use of a small bit of their minor hit “You Showed Me” on 3 Feet High and Rising. Clearing samples has become an industry unto itself, with armies of lawyers helping songwriters figure out if they’d prefer a lump-sum payment or a co-writing credit for the incorporation of their sampled song.

In that context, The Grey Album seemed especially brazen. Burton would admit he hadn’t obtained legal clearances for the Beatles tracks, but he also felt he didn’t have to: He argued that he wasn’t going to sell the album, but just give away copies to fellow producers and sample-obsessed audiophiles. He admitted there were “questions and issues” around the album, but that he didn’t “know the answers to many of them.” Defenders of the album made the case that it was very much in keeping with hip-hop’s tradition of music as collage art.

But some copies did end up for sale on eBay, among other outlets, and others popped up online. Jay-Z and Paul McCartney both seemingly had no issues with The Grey Album; Damon Dash, then working for Jay-Z’s Roc-A-Fella label, enthused about the way it brought “two great legends together.” But EMI, which controls the publishing rights for the Beatles’ records, was not so forgiving and sent Burton a cease-and-desist order, after which he yanked it from his website.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

To protest EMI’s action, nearly 200 websites offered free downloads of the album on February 24, 2004 — “Grey Tuesday,” it was called. Those sites were also hit with legal letters, but that day, more than a million copies of The Grey Album were supposedly downloaded. Had it been an official, legal release, The Grey Album would have been one of the best-selling albums of that year.

Next to the seamless samples of modern pop, The Grey Album sounds almost primitive; the musical stitches are easier to spot, and at times it feels a little forced. But the album remains startling and clever (and absolutely better than most of the brutish rap-rock fusion that preceded it). The blend of Jay-Z’s narrative of his life in “December 4th” with the acoustic guitar loop from “Mother Nature’s Son” works on musical and lyrical levels, as does the combination of Jay’s anti-media tirades in “99 Problems” with the discordant riff from “Helter Skelter.” I still love the way John Lennon’s “Oh, yeah!” exclamations and George Harrison’s grizzled guitar in “Glass Onion” push along “Encore,” and how the stately piano from “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” propels Jay-Z’s retelling of his career saga in “What More Can I Say” (even if the line “I’m at the Trump International, ask for me” now jumps out, and not in the best way). The album remains what it always was — a lively, mind-bending experiment that doesn’t negate either of the original albums and, in fact, reminds you of some the glories of each.

Would we get to hear such an experiment now? To be sure, the album worked wonders for Burton, who made a name for himself with it and went on to produce records for U2, the Black Keys, Norah Jones, Beck, and others, and become half of Gnarls Barkley. But far more so than in the post-Napster days of 2004, the music business is on edge about copyright infringement. In the wake of cases like the “Blurred Lines” lawsuit, so many songwriters are being dragged into court that, as Rolling Stone reported last month, some have taken out errors-and-omissions insurance in case they need help paying for copyright lawsuits. If anyone had the notion of creating something akin to The Grey Album now, those thoughts would be quickly extinguished, considered not worth the risk and cost.

For those who want to hunt it down, The Grey Album survives, on YouTube and eBay, where freshly printed vinyl copies are for sale. In whatever form, they’re reminders of a more innocent, less litigious, and more freewheeling time — one that, in the easily rattled music world of 2020, seems ever further back in the rearview mirror.