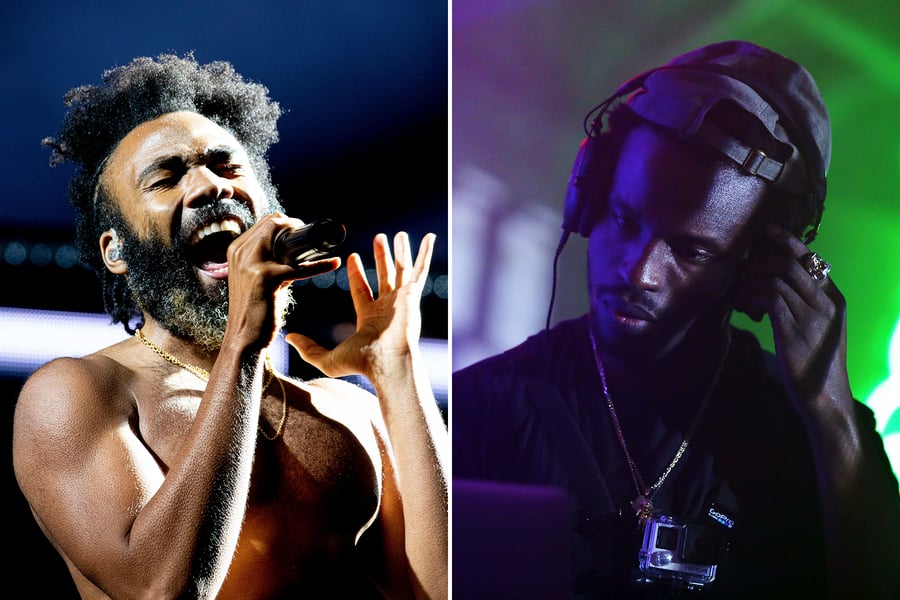

Over the past decade, Donald Glover has been building his Childish Gambino project from a side hustle to a Grammy-winning, arena-filling artistic persona. Through it all, he’s kept his circle small: His primary musical collaborator this decade has been the producer and composer Ludwig Göransson, a Swede who has known Glover since they worked on the NBC comedy Community.

It was a surprise, then, to see a third name listed prominently in the credits for Childish Gambino’s new album, 3.15.20: DJ Dahi co-produced nine of the 12 tracks. Dahi has spent the last decade amassing a star-studded but stubbornly idiosyncratic discography. He has made beats for Drake, Kendrick Lamar and Dr. Dre, but also hit the studio with Madonna and Vampire Weekend, crafted ubiquitous radio records but also taken the time to collaborate with indie darlings.

Dahi worked on 3.15.20 intermittently for over two years. He spoke with Rolling Stone about the importance of sitting with songs for a long time before putting them out and how — in his opinion — 3.15.20 is like a magic carpet ride.

How did you get pulled into working with Glover?

I knew the guys, I just hadn’t known Donald. I had known his manager, Fam [Udeorji], for years, and Ludwig as well for four, five, even six years. Me and Ludwig had worked on some stuff for Black Panther and for Creed when he was composing for that movie.

Fam was like, ‘I really want to get you with Donald and try to make something happen.’ We linked about two and a half years ago. When we finally got in the studio, it was a meeting of minds. I’m always project-oriented. I want to be there for the journey when I can — I’m always looking for opportunities to be a part of someone’s album in the sense of the whole thing. We initially locked in for a few weeks. But then it progressed to me just being around. Then you start really thinking about what we’re trying to accomplish and achieve. Whatever message you’re trying to do, I’m there to help make sure it sounds good. That was my role. We should try this, we should push that, we should pull back on this.

What was the message you were aiming for?

I’ve been pretty much in the studio with him on and off for the last two and a half years. Ludwig came in at different points in time; he’s also working on some crazy film projects. We might write a song, set it aside, come back. Try some things, set it aside, come back. There are a few songs on there we have had for a long time. We’ve been living with those: “This feels like it can last a while, it can be something that you can’t timestamp.” That’s something we were chasing. A feeling of, “I’ve heard this before,” but you can’t say, “this is from the 1960s, the 1970s, the 2000s.”

We wanted the sonics to have something warm, something familiar. Also we wanted to not get wrapped up in giving people hits and make this big thing. A big part of this is community. We want it to be an album you can share with your grandmother and an album you can share with your kids. You can include your family in it. That was more of a goal than, “make a single.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Several of these songs have been floating around for a while.

“Algorhythm” has been around. He performed that on his last tour. That was one that felt like either the beginning or the end of something. “Time” has been around a long time — I think we started that idea the first session that we got in and worked together.

I’m trying to think of the titles but then obviously these songs aren’t titled. The “[Feels Like] Summer” record [labelled 42:26 on the album] is old. The record that’s like “why go to the party?” a capella [39:28 on the album], that’s an older record, though we modified it over time, added some things. So almost half the album is records we’ve had and just been sitting with.

To me it’s good to know that records can live past a moment. Sometimes you get hyped about something, it sounds cool, but the moment goes by, the time and space you’re living in changes, and then it doesn’t sound that good. I lived with this stuff for such a long time. But I still listen to the album.

How did songs evolve as you sat with them?

The whole process for us was the jam. For “Time,” I came up with some chord melody ideas. Ludwig came in and started writing changes in the chord progression. Donald came in and laid some initial thoughts. The beginning of that record is totally different from when it is now. It was a lot more somber, a lot more heavy feeling. But I always loved the lyrics, the idea of things being very final.

We started letting other people hear the record, touch the record. We wanted to change the groove of the drums, and my boy Chukwudi [Hodge] came in and gave some crazy drum ideas. Then Ludwig reimagined the chords, made it sound a little brighter. Ely [Rise] came in and added some dope synth lines and another chord progression change. It kind of went through a factory line — everybody touched it at different times and added to it until it got to the point where it is now.

That is probably the record I’m most proud of. It’s the first song I did together with Donald. It wasn’t on the album, then it was, it changed, it came back — it meant something to the project.

Are you used to working that way?

Working on this album was different: The music kept evolving. And this was the first time I really had a chance to work heavily with a lot of talented musicians. You have an initial idea, and you sit with it for a while, and there was so much musicianship on this that things kept evolving to the point where it was like, I couldn’t even have imagined it being this way. Ideas are never done until you give up on ’em. On this one, we just kept trying.

Several of these songs change modes — “12:38” goes from the seduction funk to 21 Savage talking about police harassment, and “24:19” starts low-key and ends like an anxiety attack.

“12:38” was an evolving thing, too. We had an initial beat idea, and Ely had some good chords. To me it felt like, this is a simple, feel good record if we get it right. But for a while, we couldn’t figure out what it was for. Khadja Bonet came in and sang some parts for another record, and then they were chopped up and put in this record. It ended up having kind of The Love Below energy — funky, odd, but feels good. It kind of got set aside. But then Donald started to figure out what he wanted to say on the record. We had the 21 verse for a while. Ink was a songwriter who came in just to help write on the record. We took our time. We tried this, tried that. That’s in the year-and-a-half-old range.

When I explain it to the guys, the team, I always say the album felt like a global journey. You feel like you’re in different parts of the world. In my imagination, you’re on a magic carpet, flying over different parts of the world. You listen to someone’s conversation — “ok, cool, let me fly over to this country.” Then you go here. Then you go back in time. The transitional things are part of that. Just follow it and get to that end point.

Do you think there’s an artistic reason for the time stamps? To push the focus onto the whole album?

That’s a question to ask Donald, for sure. But goal-wise, it’s always about the whole package. The way we interpret and hear music now is very, “I can change this now if I don’t like it.” It’s easier to switch something. We want people to at least sit with the songs. It’s not about the separation of the songs, it’s about the whole.

“32:22” stands out on this — it’s more abrasive than everything around it.

The way I describe that one is if you went into some village, a tribal community of people you had never seen or heard of but were observing. That song is supposed to be an insight into a spiritual celebration of some sort. Going to a place, experiencing something, not just saying, “I don’t get it, I don’t understand.” Sometimes it’s good to be in an uncomfortable situation. That song, for me, does that. I always loved it because it doesn’t sound like anything anyone specifically is doing. It’s this tribal experience we don’t get to hear in our pop-world of music making. And there are only a few artists who can get away with that. Donald can do that. For a lot of artists, there are rules — you can’t do certain things. But he’s able to tap into something that others aren’t. This is one — I don’t know where anyone else is gonna try this.

Most people are probably unlikely to try the next song, too, which starts with cows mooing.

Again, I don’t know who else is gonna do that record, with the very happy, backyard barn sound music, the pleasant guitar, but then he’s talking about some drug references. What’s going on? It’s this uncomfortable space that we get to go in. It feels very personal, and he’s the one who does that. I can’t think of another artist who can occupy that space and feel genuine.

That’s what’s interesting for me: To work with someone who can, a lot of times, do whatever he wants. A lot of artists don’t get that opportunity. They have to stick with the narrative of, “I’m this.” I haven’t really worked with an artist like that [where they can say] “I don’t have to make this type of record.” Certain artists know their bread and butter. I want to be in a space where you love it or you hate it. The other stages of making songs feel boring to me. I don’t like to sit in the middle. Everybody else just sounds safe. That’s cool for other people, I’m not hating on it. I just don’t like sitting in that space. And me and [Glover] really connect on that idea. Let’s try some stuff.

Did you know he was going to upload the album for 24 hours then take it down?

I didn’t know nothing about that. With the album being released the way it was, it was confusing the idea of a traditional release. But it makes sense for now. The main goal is to have people sit with it, understand the flavors. It’s hard to get those moments from people. This is the one time nobody can go anywhere. So sit with this.