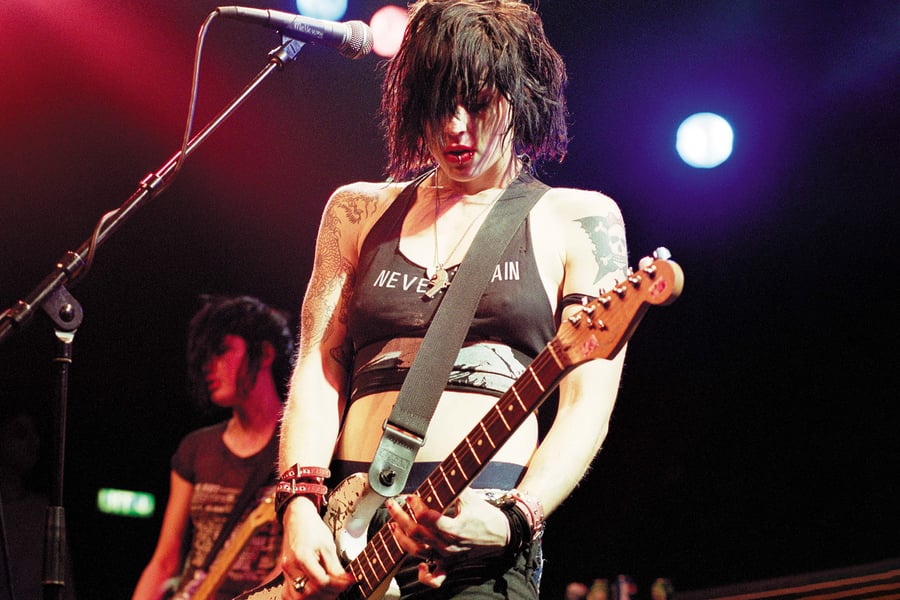

Brody Dalle is rarely seen without her sneer. It was there last year, when she was mugging into an iPhone camera, posting from the road with her punk band of two decades, the Distillers. It was there a month into the pandemic, when she Instagrammed her quarantine hair. It was there last summer, as she teased fans by posting from the studio, revealing that she and her bandmates were in the home stretch of a new record, their first full-length in 17 years. And you can almost hear a hint of it in her speaking voice — more SoCal than Melbourne these days, and less raspy than one might imagine, given the guttural, syllable-packed screeds found on her records — as the Australian-born singer-guitarist calls in from Malibu. But where her sneer comes through in its purest form is on The Distillers, the band’s self-titled debut.

“The idea back then with punk records was just to bang it out as fast as you can,” she says. “And if you took too long, it wasn’t punk.”

The album — which came out in January 2000, and has just been reissued in a newly remastered digital version, with vinyl to follow in November — opens with a moment of feedback, before the quick smash of snares, and Dalle’s snarled voice. “Oh, Serena,” she growls over power chords. “Oh, Serena, I know what they’re saying about you.” Someone’s talking shit on Serena, and it’s clear the woman at the mic isn’t having it. From there, the band blasts through 14 more songs in just over 30 minutes — some harking back to Dalle’s girlhood in Melbourne, Australia (“Gypsy Rose Lee,” the hidden track “Young Girls”); some dealing with the divisiveness she encountered when she moved to Los Angeles at 18 (“L.A. Girl,” “Girlfixer”); others referencing the documentaries she watched on world revolution (“Idoless,” “Red Carpet and Rebellion”).

While the album’s songs took cues from the Nineties pop-punk mainstreamed by Green Day, the Offspring, and her then-husband Tim Armstrong’s band Rancid — “I think I was really impressed with the way he sang,” she says — Dalle twisted the genre into something unique, barking calls for teenage uprising and observations from the girls in the pit. The Donnas and the Lunachicks had packaged that sound into something more palatable, but the Distillers were like a band you might find playing your friend’s basement. And they were fronted by a woman who looked like she could kick your ass and steal your boyfriend — but who sang about how such petty confrontation was, in fact, the problem with the scene. “I did experience a lot of cattiness” within the L.A. underground, she says. “And I just don’t operate like that.”

Dalle had moved to Los Angeles in 1997, when she was in her late teens, to be with Armstrong. A couple years before, they’d met at the Summersault Festival in Australia, where she was playing with her band Sourpuss. He invited her to America, and Dalle — using money she’d won in a settlement with the government after she was sexually abused by a friend’s dad — made the trip. There, she immersed herself in the SoCal punk community orbiting Epitaph Records, and went about putting together a new band. She found bassist Kim Chi and Matt Young, and in 1999, the new group put out a four-song EP on Armstrong’s fledgling label Hellcat. They added Rose Casper on guitar, and their debut was released the following year.

The Distillers shot on to success, releasing Sing Sing Death House in 2002, and 2003’s Coral Fang, which included the single “Drain the Blood,” and brought them radio play and some MTV fame. But each album featured a different lineup, and each was a little more refined than the last. The Distillers remains the grittiest of their releases, with the urgency of teenage aggression, friendship, and heartache steeped in fast guitars and slamming drums. The Coral Fang lineup reunited in 2018 for a series of shows and a seven-inch, and have been working on a new album, though no release date has been set. (“I’m so fucking excited for this record to come out,” she says. “I have never been more proud of a record than this one.”) In the meantime they’re playing one-off gigs, like a virtual, acoustic Halloween-themed set on October 30th.

Earlier this fall, Dalle got on the phone with Rolling Stone to reminisce about what it was like to be the young, crazed girl who made The Distillers.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Looking back on The Distillers 20 years later, how do you feel it holds up today?

I feel like the melodies and the hooks still stand up — even though I feel like it’s the equivalent of having someone read my teenage diary. Not because of the content, but because it’s so immature. I still love the record; the influences at the time are so immediate and obvious. I was trying to find my sea legs, in terms of writing, getting the melody to fit with words. That was my first foray into that realm and I struggled with it, but everyone goes through that phase.

Had you been writing these songs throughout your teenage years? Or were they mostly written when you got to L.A.?

Well, “Blackheart” I think I wrote when I was like 15. And then the rest of it I wrote in America. The first song I wrote in America was “L.A. Girl,” which I wrote on my ex-husband’s upside-down left-handed guitar, because I didn’t have a guitar with me. So, yeah, I kind of had to figure out how to play guitar backwards, which is good for you; it’s good for your brain.

How did the Distillers originally come together?

Because of my ex-husband’s life and social circle, I was kind of just immediately dumped right into the whole Epitaph scene. And he, at the time, was starting up his record label, Hellcat. So I spent a lot of time there — day in and day out — because I didn’t know anywhere else, and didn’t know anyone else. And having played in bands pretty much my whole teenage life, playing music was a compulsion for me, a necessity.

And I started looking for people to play with, and someone highly recommended Kim [Chi], and said she’s a badass bass player. It turned out that she most definitely was, and still is to this day. She can out-fucking-play anybody. And then I found [drummer] Matt [Young] through the Adolescents. We started playing at a rehearsal space in Hollywood, and then started doing small shows, mostly in Orange County. And we did a couple tours, and the rest is history.

You’d made the seven-inch with Kim and Matt and then brought on Rose Mazzola for the album. How did that change the dynamic of the band?

I just really loved that there were three women up front, and these women were able to sing the other parts. It just was powerful, and super cool. I loved it. But there were struggles. There was Rose, she was young — like 16, 17, and she had some serious kind of issues, teenage kind of complications, and drug addiction on top of it. So, I was basically her babysitter and I had to take care of her, which I didn’t mind because I absolutely fucking adore her. And she lived with me mostly in L.A. But then sometimes with band dynamics, especially for me leading the charge — people either are totally willing to go along with your plan, or have a plan of their own, or don’t like your plan. And I felt like there was a collusion going on. I wanted to go in a certain direction and they didn’t. So I had to let them go.

How were you treated when you were introduced to that Epitaph scene in L.A.?

I was treated mostly really well. I think there was some suspicion initially about what my motives were. So that was difficult to work through. I have definitely struggled throughout my life with dynamics with women, either as a kid at school being left out and bullied, whether it’s physically or just, there’s the group of girls standing in the corner and there’s me sitting by myself at lunch and they’re talking about me. … But it’s just life experience and healing those kind of deeper, darker parts, and coming out the other side.

The debut album features various female characters, including Gypsy Rose Lee and Gerti Rouge. What do they represent to you?

Gypsy Rose Lee was from my childhood. I had a childhood friend, and we would play this game where she was Gypsy Rose Lee and I was Marilyn Monroe and we would dress up. We were really little, like eight years old. She was a Sagittarius, and I think Gypsy Rose Lee was a Sagittarius. I can’t remember, but somehow that tied into it. And then Gerti Rouge is a pseudonym for my childhood best friend whose dad sexually abused us. And we eventually ended up taking her dad to court and she lived with my family for about a year and then ended up in a women’s refuge. So yeah, that’s who Gerti Rouge is.

And the song “Oh Serena” seems to touch on some of those same themes — being rejected, being sexualized. Was she also a person in your life?

Yeah, it was a made-up character based on experiences and being treated a certain way, or seen through a certain lens that comes out of childhood pain, which ends up in promiscuity and then how people treat you when you’re trying to process and work through and understand your own demons, and your own pain. I guess not being allowed to have that space to do it, and just kind of being typecast as a slut.

On the Distillers’ second record, Sing Sing Death House, you get a bit more political, but those themes start to creep in on this album, with lines about religion and uprisings and revolutions. What was pushing you to write about that at the time?

I was watching a lot of documentaries about world revolutions, and then trying to write in narratives. But that first record was so difficult for me to make the words fit. I try to sing those songs now, and I’m like, “What the fuck am I even saying?” Like, “What is this?” I’m having to put actual words in there, essentially rewriting the songs, but you live and learn. I don’t know if you’re going to ask me about The Village Voice?

I was! [Ed. note: The Village Voice ran a review of The Distillers when it came out in 2000, criticizing the sometimes-nonsensical lyrics.]

We got the review in The Village Voice, and it was scathing and hilarious and life-altering, basically. The reason that my lyrics are so succinct on Sing Sing Death House is because of that review, where he says, “What the fuck does this even mean? That’s not even a word.” I had an actual copy of it. In fact, I think I read it in New York, which probably really made it much worse. And I just wanted to run and hide and not be seen anywhere. No holds barred — just straight-up brutal honesty. I’m super grateful for that, because it kind of set me on a different trajectory, where I had to really fucking buckle down and know what I was saying, and make it all come together.

Are there any particular lines on the album that stick out to you now?

Oh, my God. Well, I mean, there’re songs like “Red Carpet and Rebellion” that was about — I ended up living in Geelong, which is like an hour outside of Melbourne in a beach town. The house was this old Seventies house and it had bright red carpet. And I kind of tied that into the Russian revolution somehow. I don’t really know what I was thinking at the time, but there was a lot of young teenage rebellion going on in that house and different dynamics between people. So that was my exploration in that home.

What do you remember about the recording process? Did it take you guys a while, or was it a pretty quick thing?

Oh, no, it was fast. I don’t even think it was a week. It was probably like three or four days. And that’s recording, singing, mixing, mastering. There was a lot of stuff going on; there was someone who contributed to the record who was going through a really, really fucking intense situation in their marriage and they had a young child who eventually died and I had been taking care of her and it was just fucking brutal. It was so brutal to watch that person go through this fucking devastating tragedy. Taking care of this little girl who died is fucked up.

Do you think that kind of played into your creative approach — this intense tragedy happening around you?

Yeah. It kind of tied into “Young Girls,” even though “Young Girls” is about Gerti Rouge. It kind of had a color of that — like neglect, deep childhood pain.

And what made you want to include Patti Smith’s “Ask the Angels” on this album?

Well, I love that song and I had played — or maybe my ex-husband played a show and I met her. I just love that fucking song, man; it’s a powerful song. That record is incredible, and I was just listening a lot to her at the time, and I wanted to sing that song, and also put a different flavor into the record, too, so it’s not just all this intense, fast punk. There always had to be one mid-tempo song. That was the rule — maybe two but never three.

What else were you listening to at the time? You said before that you feel like your influences were very obvious on that record, but I’m wondering what you hear when you listen to it?

Well, I definitely hear my ex-husband’s band. I hadn’t really found my thing, or also the thing that I had before wasn’t cool enough in the eyes of the peanut gallery, so I felt like I had to try to fit in — and it’s just so glaringly obvious. But I tend to listen to stuff that doesn’t influence me, as well, like I was listening to a lot of Lady Saw, who’s a dancehall artist from Jamaica. And my favorite song of hers is “Sycamore Tree,” so I think I listened to that song about a thousand million times. I’m trying to think of what else I was listening to — a hell of a lot of X-Ray Spex, and probably Black Flag and Dead Kennedys, for sure, and Blondie. Blondie was something I had on repeat a lot back then.

Has the way you think about writing songs changed during the last 20 years?

I mean, it’s usually directly related to whatever I’m going through at the time, mixed with a deep well of childhood pain. So, it’s whatever’s happening in the present time, and somehow it’s about the evolution of your person, your spirits, your behaviors, your psychology, and then seeing it through a filter, or seeing it through other situations, other people, other scenarios, telling stories that you can relate to. And I think over the years I’ve gotten a little bit more comfortable with being more personal and more direct in what I’m saying.

But I started writing poetry when I was, like, eight years old and I was lucky to have a woman across the street — her name was Jacinta, she worked for the Age newspaper in Melbourne, which is the main newspaper, and she was also a poet. In exchange for babysitting her daughter she would help edit my poetry. I was super grateful to have her mentor me in that way. So, I mean, lyrics were super important to me; they were one of the things that I work the hardest on.

The lyrics on this album chronicle the experiences of a very young woman. Your daughter is 14 now — watching her grow up, do you have a different perspective on how you were processing everything you were dealing with at that point?

I mean, when you’re a teenager, you feel like you’re so much further ahead of where you actually are, and you have all these beliefs and feelings that are so fucking intense, and I think it’s just a natural progression. But yeah, in hindsight, looking at her and even looking at my boys, it’s like, they’re just so young. I think when you’re a teenager it’s hard to encapsulate or understand, or be able to step outside of yourself without that life experience. So things can be so final and so fucking passionate with no room to compromise, or to see other viewpoints. And it’s through that process — dating and arguing and discovering and listening to the older people who mentor you or people you respect — you start to kind of figure out your values and your beliefs and how they fall into your life and what everything means. It’s a crazy, awesome process.

In a similar vein, what advice would you give to the Brody making this record? Both musically, and how to handle being in a band that got this big.

I don’t think I would give advice.

Yeah?

I think it would just be, push yourself. Because the thing is, when you’re younger and just in general, my personality, I don’t like to be pushed around. It’s hard to be … I’m trying to think of the words. I don’t know, I’m stubborn, you know what I mean? You have to kind of get slapped around a few times before you’re like, “Oh, shit, OK, I get it.” So, everything happened the way it did; everything happened for a reason and it was just meant to be. I don’t think I would interfere with that. I may just be like, “Push yourself, keep going; push to get the best thing that you can out of yourself.”

What are you most proud of about this album? Why do you think it resonates so much now?

I’m proud of, I think I said earlier, just the melodies and the hooks. And I think without them it probably wouldn’t have carried the Distillers where the Distillers ended up going. And it’s just, like, my first real record-making experience. I was proud of working with the band and everyone’s parts and especially Kim’s. Kim’s bass playing is just fucking sick. And then I think when Kim and I sing together, it’s really awesome too. And I’m definitely not proud of my lyrics.

Have you kept in touch with all the ex-members?

I sometimes talk to Kim through Instagram DMs. And then Rosalyn and I speak, too, and I follow her on Instagram as well, and I spoke to her maybe a year and a half ago. She called me to apologize and also say thank you, which of course I never even for one second thought that was necessary or owed or anything like that, but I think because she’s sober and clean she was having a moment of clarity and I don’t fault her or hold anything against her. She was just a kid. And it was my pleasure to take care of her and kind of mentor her and just watch her go through her own process. She’s so fucking cool and beautiful and she’s still making music and she’s has a really incredible voice. And yeah, my thing was, Rose was just really special. I just loved her like a sister.

Would you ever try to get that original lineup back together for a show?

Yeah, maybe for fun, for sure. I mean, it’s definitely crossed my mind, but I’d have to run that by my guys and see if it makes sense. Everyone’s kind of in different places, but yeah.

From Rolling Stone US