Brendon Love’s Invisible Enemy: The Teskey Brothers bassist details his journey with depression

Brendon Love’s Invisible Enemy: The Teskey Brothers bassist details his journey with depression

When The Teskey Brothers’ sophomore album Run Home Slow hit number two on the ARIA chart, sandwiched between Ed Sheeran and Northlane, there was a laser-focused concentration on the band of brothers and friends from Warrandyte Victoria. Just two years prior, the band broke into the mainstream and toured the world with their now trademark brand of slow-burn heartbreak and blue-eyed soul.

That attention deepened following the release of 180 Grams, a podcast series from Mushroom Group that unpacks “remarkable albums”. Run Home Slow certainly fits the bill. The album recording began at the home studio of Sam Teskey with a singer who couldn’t sing (Josh Teskey lost his voice after catching a nasty cold), a producer who was navigating a divorce with a seven month old baby back home in the UK (Paul Butler) and a tape machine that broke down on the first day of recording in analogue format.

However, it wasn’t the marital issues or the recording hurdles that led many listeners to reach out to the band with their love and support. Nor was it these hurdles which lead to The Teskey Brothers entering regular, self-imposed group therapy together. It was bassist Brendon Love.

Content warning: This article discusses depression, suicide, and other difficult topics.

Brendon Love has been with The Teskey Brothers since the band’s inception in 2008. Childhood friends with Josh and Sam Teskey, Brendon has a sense of humour worthy of a stand-up comedy tour, the guitar chops of John Entwistle, and the work ethic of Beyoncè. He also lives with clinical depression.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

The brief for the 180 Grams podcast was simple enough, just talk about the second album. But as we soon found out, you couldn’t talk about Run Home Slow without talking about the events which led to Brendon Love skipping a North American tour after recording wrapped up to enter a health facility.

Speaking to Rolling Stone Australia over Zoom, Love wastes no time doing what he later tells me is called “deflecting”.

“Might I say I thought we were here to discuss my love of Shaun Tan novels,” he jokes. “I heard nothing about mental health.”

Photograph by Al Parkinson

Take a cursory glance at Love’s Instagram page and you’d believe he is the life of the party. One video shows him reacting to a viral clip of Chris Hemsworth; the one where the film star offers up a swathe of compliments, direct to camera.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CEvTDqWBWU-/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Love plays along, rotating between bashful and flirtatious as he reacts to each compliment. But just as we don’t believe Ozzy Osbourne is a bat-eating beast offstage, or that Marilyn Manson doesn’t revert back to Brian Warner in the comfort of his own home, Brendon Love is more than just his Teskey Brothers persona.

In some circumstances, he’s the centre of attention, moonwalking across the stage and pulling vocalist Josh Teskey into a galloping ballroom twirl. In others, Love recoils from the spotlight and, god forbid, the praise that comes with it.

At a sold-out show in London in 2018, the band finished on a high. The crowd at the Omeara were like putty in their hands, engrossed in every note. For Love though, the success that night only exacerbated his imposter syndrome.

“It couldn’t have been a better gig objectively. But I just felt the worst I’ve ever felt in my life. People were coming up to me after the show and saying, ‘Oh I loved that so much’ and being really lovely and sweet to me. But I was like, ‘Argh this is making it worse’.

“I don’t know what that is,” he adds. “I think it’s maybe because you feel you don’t deserve it. You feel like a fraud or something.”

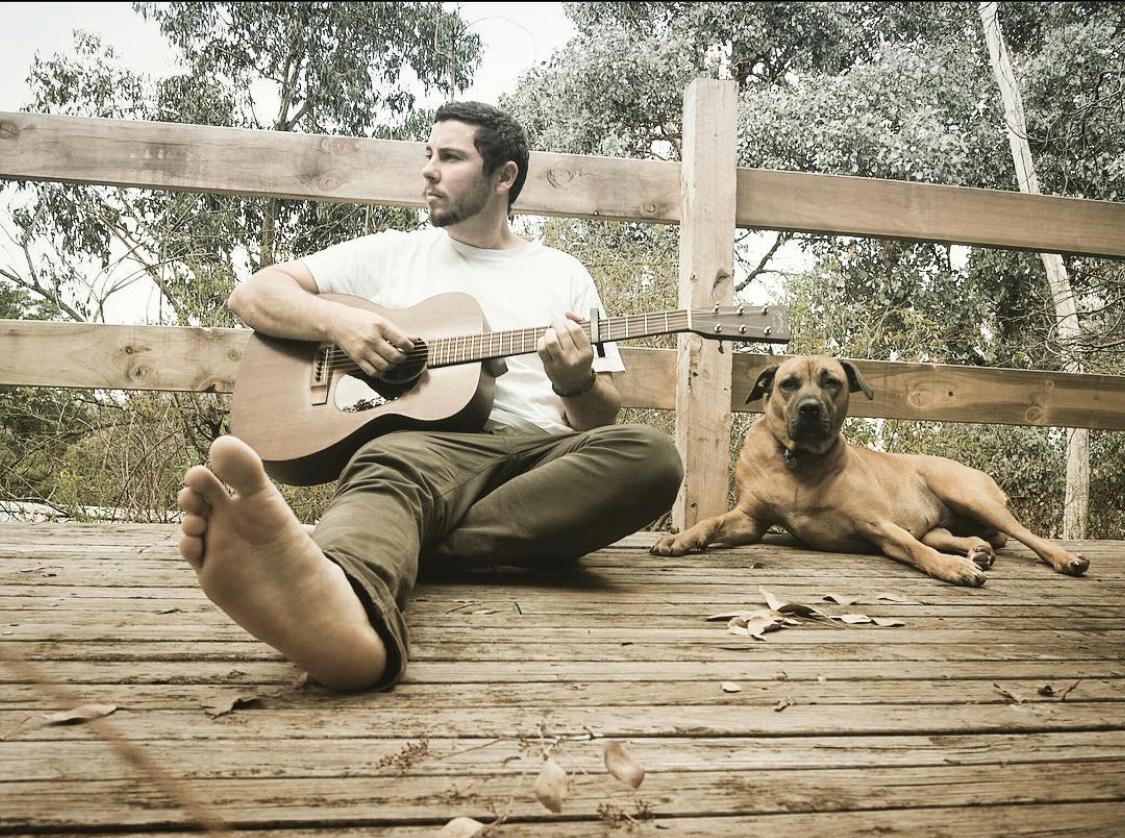

Brendon Love’s dog Clarice is laying at his feet while we talk. Bounding into his life five years ago as a rescue, Clarice offers routine and daily exercise for Love and acts as a reminder to keep his spirits in check

“She’s like the conduit for the world’s sadness,” says Love, only half-joking. “[…] It’s like Clarice is the ultimate empath. She absorbs everything around her, so she has these constant sad eyes which breaks my heart.”

Brendon Love with Clarice

Interestingly, there was one point where both Love and Clarice were on the same medication for their depression, they took their meds at the time together each day. The only difference was the dosage.

As a textbook introvert whose parents and brothers all have similar personalities, Love calls his personality type and upbringing a “perfect storm” for neurotic depression.

“Everyone has different personality types which are predisposed I guess to certain patterns of behaviour and feelings,” he says. “And you know, me being quite an introverted sort of insular person, it’s kind of this perfect storm.”

15% of the Australian population are living with some form of mental illness. One study indicates that one in six Australians is currently experiencing depression or anxiety or both. That’s equivalent to 3.2 million people today. Over 65,000 Australians make a suicide attempt each year and eight Australians die every day by suicide, the annual deaths in Australia wouldn’t even fit in Sydney’s Enmore Theatre.

Writer and historian Andrew Soloman has said the stigma attached to mental illness is subsiding. People living with a mental illness are no longer considered unreliable or even dangerous as they were in our recent past. Thanks to more people speaking up and out, we’re starting to understand just how ubiquitous it is. From Grammy nominated artists, to scientists, labourers, Peabody Award winners and retail assistants, mental illness doesn’t discriminate – and it also doesn’t always stop people from achieving great things.

Brendon Love was 15 when he first heard a personal hero speak up about depression. Paul Dempsey’s solo work has charted his bouts of clinical depression and ensuing writer’s block since the release of his Counterfeits and Forgeries EP in 2009.

“About the only thing time will tell/Is you to go fuck yourself,” he sings on the first line of “Nobody’s Trying to Tell Me Something”.

“That was the first time that I’d heard anyone sort of speak about it openly, in public. Particularly someone I idolised,” says Love, remembering Dempsey’s live show as a 15-year-old. “For me yeah, that was a big moment because I was like, ‘Oh wow’.

“He was just up there and talking about it so matter of fact and there was no shame in it. […] It was just like, ‘You know, got a bit of a cold’. It was just any other health thing and so that was a big comfort for me.”

It would take another 14 years before Love was officially diagnosed with clinical depression, in August 2018. Despite his understanding that depression is a common condition – and that even his musical heroes live with it – his perfectionist disposition at railed against the fact.

“It almost felt like my ego was telling me it was a cop-out and it wouldn’t allow me to have an explanation,” he admits. “It was almost as if I felt like I deserved to feel like this. And so therefore any form of understanding was like met with a bit of resistance.”

If you haven’t picked up on it by now, Brendon Love is a fascinating and complex person. It’s a natural assumption to think a band of brothers and friends who teamed up as teenagers would indulge in drugs and alcohol – at least in the formative years. Not for Love. Through a decade with the band before they were discovered by Marihuzka Cornelius at Mushroom Group, throughout their underage years sneaking into local gigs around Melbourne’s Yarra Valley – not to mention a full decade of youthful adventures before that – he was sober. He always has been.

“33 years sober I like to call it,” he grins.

Brendon Love was born with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, a rare genetic disorder that has been labelled “the most severe form of hereditary emphysema”. In hindsight, the rules around Love’s disorder – no alcohol, no smoking, no drugs, no smoke-filled bars for extended periods – all create the perfect environment for someone putting their mental health first. According to a study by the British Journal of Psychiatry heavy alcohol consumers had a five-fold higher risk of suicide than social drinkers.

In reality though, a keen concentration on physical health directly rivals against the life of a touring musician.

“It’s not what you think of when you’re nine years old, dreaming of being you know, a touring musician,” he says. “[…] There’s no manual.

“The demands of the job are certainly direct challenges to the three most important factors of mental health. Which are you know, sleep, good diet and exercise,” he lists, “and just routine in general. […] It’s up to you as the individual to help create the business that can be understanding and support mental health in that way and prioritise it.”

Photograph by Sanne Gault

In the days before the recording of Run Home Slow, The Teskey Brothers were in survival mode. In the midst of an Australasian tour the band were tapped to write seven original tracks for the Palm Beach motion picture soundtrack. Sync jobs are great revenue runners if you can get them, but they’re often written to brief and involve more back and forth between brand and band than many artists are used to.

“Anything that you can do in the music industry to remunerate your skill set, is what we were doing. We’d never had a busier year,” says Love.

Add to that the fact Love had taken on the role of producer in the initial stages of pre-production. This meant he was facilitating all of the pre-production sessions, managing session players, and scheduling and liaising with management and the label.

When the album recording was almost done, when producer Paul Butler had flown back to the US – and the band had completed an ambitious European tour – Love found himself completely unable to recalibrate, let alone celebrate.

“That’s when it hit me that, ‘Oh hang on, the workload’s done and I still feel like absolute shit’. You know what I mean? I can’t blame this anymore on sleepless nights and stress, and labels and a producer. You know, and a soundtrack. All of that is done,” he continues. “And I’ve got two weeks off, I still feel absolute like shit, and I have no sense of accomplishment or joy in my life whatsoever.”

Listen to The Teskey Brothers’ Run Home Slow:

As the band readied themselves for another tour, this time through North America, Love made the decision to stay home.

“I was in a bad place, no other way to put it. I just wasn’t thinking clearly… Not only did I not know the steps of getting treatment, I couldn’t even fathom wanting treatment or doing anything other than either rotting in bed or taking my own life.”

On the advice of his psychologist, Love checked himself into a mental rehabilitation centre as an outpatient and started taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a widely prescribed type of antidepressant medication.

“I knew if I went on the tour, one, I wouldn’t be healthy. And two, I’d be putting off treatment again,” Love says. “So I just wanted to draw the line in the sand and go, ‘it’s time to move forward, I’ve been sort of pushing this away and pretending it’s not happening for too long’.”

A Productivity Commission draft report on Australia’s mental health system (published last October) estimates that mental ill-health and suicide cost Australia approximately $130 billion every year. Love may have just learned about the Medicare rebate for his mental health plan, but rising numbers in mental illnesses suggest an overhaul of the current system, especially in relation to access and funding, is greatly needed.

As the effects of COVID were being felt across the country in May, Sydney University’s Brain and Mind Centre teamed up with the Australian Medical Association to construct a modelling on the mental health impacts of the pandemic. The findings suggest we could face a generational crisis with suicide rates rising as much as 50% over the next five years.

We’re already seeing signs that support the modelling. In August alone Lifeline was receiving a call every 30 seconds totalling to about 90,000 calls a month to the one provider. Meanwhile, Beyond Blue said more than 500,000 people have accessed their Coronavirus Mental wellbeing service.

Love made the right decision to sit the band’s last overseas tour out. He was growing irritable in the final recording days and his workaholic, perfectionist nature meant he was a stickler for nuance. Producer Paul Butler said the back and forth over how many tambourine hits should be included in the single ‘Hold Me’ lasted four days (it’s seven).

In the studio and writer room, Love fits the classic passionate schoolteacher trope, he expects a lot but he gives a lot in return. When asked how the North American tour went without Brendon Love, the band gushed over an “indescribable quality” that they genuinely missed.

“You don’t notice what you’re missing when he’s playing until you work with another bass player,” said Sam Teskey on the 180 Grams podcast.

That Love inspires this kind of loyalty is striking. While the band have spent the last 20 years together, they are now at a level where artists from varied genre backgrounds would be vying for a spot on the venerated train. The band are his equals, and yet, they’re inspired by him.

“It was lovely to listen back to on the podcast,” Love says. “I feel that I’m in such a better place that I’m open to receiving compliments in that way. Whereas you know, had they have said that a year ago it probably would have made me feel like crap.”

Instead of splintering off separately as many band members do after an album and the ensuing promo has wrapped up, the Teskeys stayed close. The introspective nature of the podcast, where each member was given space to reflect and listen back on each other’s experiences, changed the band forever. The Teskey Brothers now come together each week for what they call ‘open hearts’ – regular sessions where they forget the Teskey Business and tap into the reason they all came together in the first place.

“We’re much more trying to come back to forget about the band, forget about the business. We all started as friends and [it’s about saying], ‘Let’s just remember the importance of that’.”

Love is also exploring new ground. On R U OK Day this month he partnered with music industry charity Support Act for a 90-minute free online talk on mental health.

Throughout our conversation for this article, Love peppers in a few jokes; a bit of sarcasm here, a little jibe at his predicaments there. Near the end of our chat he tells me about the messages he received following the release of the podcast. Some offered support, others needed it, and he was happy to jump on a call with them to check in.

Love speaks very seriously when he says: “There is that sort of masculine, bravado thing where it’s like, ‘She’ll be right mate’. That has such a penetrating effect in workforces and social groups. It creates a status quo […].

“That’s just so destructive for so many reasons,” he asserts. “It’s important to bring this stuff to light and make people realise that it’s just so unbelievably common.”

You can’t help but feel dejected when Love lays out the societal contribution to mental illness so plainly. But for all his vulnerability and equal courage in offering it, he also portrays the exact attitude that is needed right now; to see vulnerability as a form of courage.

For anyone seeking help, Lifeline is on 13 11 14 and Beyond Blue is 1300 22 4636.