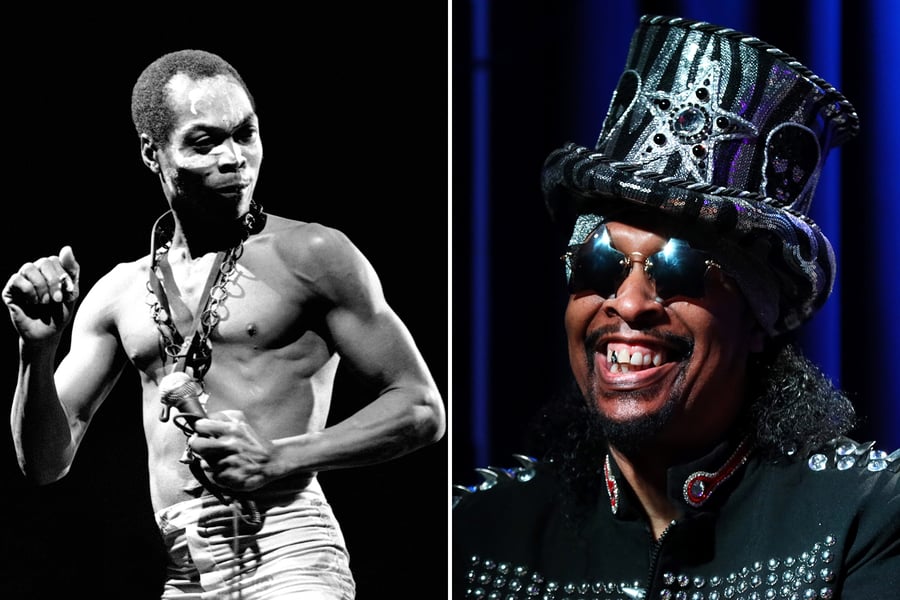

In “Viva Nigeria,” one of Fela Kuti’s earliest 45s, the Afrobeat pioneer proclaims, “Men are born, kings are made.” Kuti, who was born a man in 1938 and died a king of music in ’97, transformed his home country and the world at large into something more inclusive and compassionate through driving, dynamic drums, big, funky horns, and scabrous lyrics that skewered the violent military junta controlling Nigeria. He had studied music in London, where he played piano in jazz, R&B, and rock groups — creating a tight bond with Cream’s Ginger Baker — and toured the United States by the time he returned to Lagos in 1970. That’s when Kuti, whose mother was a feminist and labor organizer, decided to use his unique fusion of African sounds and American soul-music innovation as a vehicle for bettering the political climate of Nigeria.

It was also around this time when James Brown staged a run of concerts at a stadium in Lagos. He had recently overhauled his backing band and brought in brothers Bootsy Collins on bass and Catfish Collins on guitar, to help him realize a funkier sound on songs like “Sex Machine” and “Super Bad.” Bootsy, at the time, was still in his teens, so the trip to Africa was especially revelatory because that’s when he first witnessed the man Nigerians called “the African James Brown” — Fela Kuti, who has been nominated for a spot among the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s 2021 class — live for the first time.

Although the exact date of the concert is fuzzy — Collins remembers it taking place in March or April of ’71, but a 1970 issue of Jet suggests it was November of that year — the memory remains vivid for the bassist, who attempted some of Kuti’s rhythmic ideas on his 1976 solo record, Stretchin’ Out in Bootsy’s Rubber Band. Collins’ music from the Seventies, when he was a member of Parliament-Funkadelic, earned him a spot in the Rock Hall the year Kuti died. Here, Collins recalls, in his own words, why seeing Kuti live impacted him so greatly, as well as why the Afrobeat king is forever a legend.

We played in Lagos, Nigeria, for, I think, three days. And Fela invited us to go to his club [the Afro-Spot] a couple of those nights. I had never heard of him until we actually got to Africa. People were encouraging us see him and were telling us that he was the “African James Brown.”

When I did see him, it was so amazing the way he directed the band and the way he had the way he had the songs flowing — everything reminded me of a James Brown show. They were playing their own songs, but they had the stage presence of a James Brown show. And he would vibe with the audience. It was a powerful thing. He was a phenomenal musician.

The real kicker for me was what happened when we were on the way to Fela’s club [before his concert]. The army was in control [of the country]; they were like the police. Them cats did not play. We were doing the James Brown show in a stadium. I remember this guy comes in and told the officer that he wanted to see James Brown, and he was blind. So the officers start laughing. “OK, we’ll take you up to see James Brown.” They were snickering. So one of them takes the guy up the steps and he said, “You really want to see James Brown?” Then they beat him all the way down the steps and out of the place.

When I saw that, I was like, “Oh, man. Are we in the right place? Are we sure we can even go out to [Fela’s] club?” It was like, man, these officers who were supposed to be our protection just don’t care. That was the only downer of our time in Lagos. Other than that, it was the bomb. We had the greatest time with Fela.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

But when we were on the way to see him, in the taxi that the hotel got for us, the army guys pulled us off the road. It was me, [Brown’s organist] Bobby Byrd, my brother Catfish, [Byrd’s wife] Vicki Anderson in the back and a couple of the horn players up in the front. Of course, I’ve got my little stuff [weed], because we all want to get ready and go into the show and have a good time. So we had [the joints] out and started hooking ’em up, and the next thing you know, the army guys come to the window. I’m looking at Vicki Anderson — we called her “Mommy-o” — and I was like, “Can I give you this so you can put it in your purse?” And she was like, “Oh, no. That ain’t gonna work.” She said, “Put it in your boot.” So I put it in my boot. We didn’t know what these guys was gonna do, ’cause they didn’t take no crap from nobody. So I put it in my boot.

A guy comes up and knocks on the window, and he says, “What’s in the boot?” And I was about to crap all over myself. I’m looking at Mommy-o like, “How did he know I put that in my boot?” So I didn’t move too quick; I just sat there and looked for a minute. And then he hollered at me, “What’s in the boot?!” And I was just getting ready to open my boot and pull it out, and the driver said, “No, no, no, he’s talking about the trunk.” I said, “Oh, my God.” I was getting ready to really mess up. My heart was on the floor. Then the driver got out and opened up the trunk, and [the soldier] said, “OK, you can go.” Even the thought of what they could have done to us was incredible.

We went on to the show, and Fela greeted us and had us come to the backroom. I just threw my little stuff away, but as soon as we walked in the room you didn’t even need nothing. You didn’t have to smoke anything. You just walk into the room and you’re just done — you’re cooked. They had some bomb everything going on up in there. They had [joints that] looked like cigars. And that was like nothing to them. It was like, “Man!”

They let us come out in the front and watch from the front row. We got our eyes blown and an earlobe of sound that I would never forget. Those drums, the rhythm guitar, the bass. We had no idea that they even played normal guitars and bass. I guess they probably had just came out over there; they wasn’t like Fenders and stuff like that, but they were six-string guitars and four-string bass. They had a keyboard player, too, and I lost count on the drums. The whole front of the stage was just loaded with drummers, and they was rocking the whole stage. They were just so funky, I couldn’t believe it.

Fela would jump off the stage. He would sing. He would dance. Then he’d jump up on the keyboard. He was really deep. He was a deep guy to sit there and watch. He knew we was going to love it. You could tell he knew. He put on the best show just because we were there. I think he does that naturally anyway. He just really shined this night. And the drummers were so amazing. Words wouldn’t give it no justice. It was something you need to be in front of and feel. They were like, “This is how we’re feeling, and we want you to feel this way, too.” And they shared it with everybody.

Everybody was on the floor, jamming and dancing. We actually learned a couple of African dance moves. We saw a few people doing this one thing and it was kind of simple. Me and one of the horn players, we got out on the floor and started doing it, and the people were grooving off of us. I was like, “Wow, this is cool. I can do this.” It was a fun time.

Fela was just so powerful with it. When we were there, he had a record out under the name Fela Ransome and Nigeria 70. That was the record he had out when we were there. And you’ll get a chance to hear some of what we were hearing when we were at the club. It was just mind-blowing. What he brought was just so powerful.

After the show, he invited us backstage. He was one of the nicest guys. Unlike James, he was the kind of guy you would just love to hang with. He didn’t have all these rules and regulations. He was just a good guy to be around. The vibe was great. He was, like, a real musician. He just loved people to love his gift and what he was doing and what he was bringing to the audience. He was asking us about being with James Brown and how often we practiced. It was more like a musician would talk. I know he was getting into a lot of political stuff, but he talked to us more about the music.

And he and his musicians thought we were amazing, and that’s what really got me. They were bowing and talking about how great we were, and it was almost like they didn’t know how great they were. They were messing us up. We were like, “Y’all are the cats.” They were like, “No, no, no. You guys.” So they was praising us for how tight we were with James and how great the show was, but it was them. It was definitely them.

We never did get a chance to hook up after that, but his music had an influence on me. It soaked in so much that when you listen to “Stretchin’ Out,” you’ll hear the African root on the kick drum that stayed with me for years. We didn’t get to record “Stretchin’ Out” until 1975, so for all those years I was like, “I’ve got to lay this groove down that I remember from Africa.”

To me, the feeling part of what Fela and his band were doing meant more than anything. The way they made you feel was some undercurrent funk right there. It was the undercurrent that you don’t really get to hear. On Minimoogs [synthesizers], they’ve got an oscillator that you don’t really get to hear, but you feel it; that’s what was going on in Fela’s rhythms and the music. If nothing else, they should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for that. You didn’t even have to see them. When they played that music, you felt you saw them, and even if you couldn’t dance, you was dancing. And that’s that undercurrent funk. That’s what Fela had: that undercurrent funk.

From Rolling Stone US