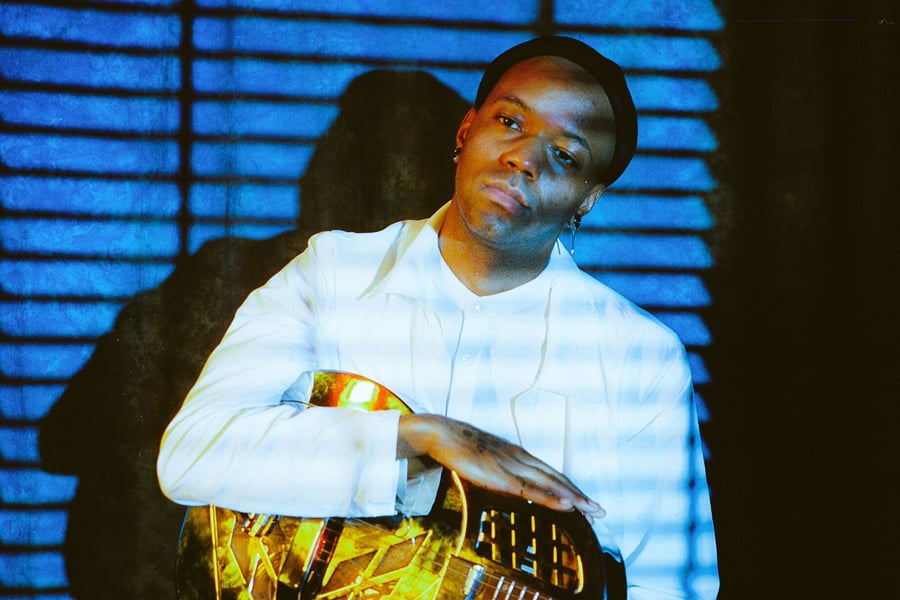

Carl “Buffalo” Nichols knows the question is coming, and he can’t help but smile. “Should I be careful or should I be honest?” he says, Zooming in from a hotel room before a show in Englewood, Colorado. “You know, this is a very loaded question.”

The question: “Where does the blues stand in 2022?” It’s a salient one for Nichols, a longtime Wisconsinite now based in Austin, who last fall released his debut record, a largely acoustic set steeped in the history of the genre. The album received generous praise, and helped get him his current gig opening for Houndmouth; in May, he’ll open a string of dates for Valerie June.

Nichols, 30, is part of a new generation of traditional-minded blues artists, along with acts like singer and guitarist Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, who’s up for a Contemporary Blues Album Grammy this year. Yet many of these rising stars feel like outsiders in their own genre. The blues album charts are consistently dominated by white artists, and when young acts sign up to play blues cruises, they find the decks packed with largely older, white crowds. “We’ve tried to preserve as much as we can, but the audience is primarily a white audience,” says Roger Naber, who runs the Legendary Rhythm & Blues Cruise. “It’s for people with money to take a cruise.”

For every Robert Cray or Gary Clark Jr. who’s broken through in the last several decades, many more white blues acts — from Eric Clapton to Stevie Ray Vaughan and George Thorogood, up through the Black Keys — have sold more records and had higher profiles. Judith Black, the newly appointed head of the Blues Foundation in Memphis, admits she was taken aback when she started her job last month. “Stepping into this role, I was introduced to far more white blues artists than I knew existed,” she says. “I was surprised at how few African-American blues artists were really being seen and heard right now.”

Nichols is unapologetically blunt when he discusses the way the music he loves has become disconnected from its cultural roots. He admires the way someone like Jack White used the blues as a jumping-off point for a style of his own 20 years ago. But in general, Nichols is rattled by what the traditional blues scene has become.

“So much damage has already been done that getting somebody under 35 to even consider listening to the blues is such a struggle,” he says. “From where I’m sitting, there’s a lot of great potential, but the potential is limited by the old guard, all the older white guys who have been doing it. They’ve ruined it for everybody else. And they’re still there and they’re still taking up way too much space, and they’re still making terrible music.”

His critique of the last few decades of traditional blues stars is unsparing. “Those Seventies and Eighties blues men took on these Black stereotypes and made this new stereotype of bad, ‘your uncle’s band in a garage’ blues music,” Nichols continues. “That’s what people have in mind when think of the blues. So when somebody younger comes along, they don’t even see a place for themselves. It’s already been so far removed from anything recognizable from what Black people have ever done. And then you have this really difficult question of, ‘How do I fit in — or do you even want to fit in?’”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“I can see his point,” says Cray, who, at 68, feels like the old guard himself. “That’s been going on for the longest time. In our early days, Black fans wouldn’t come to see the music. More and more Black people are coming to the shows now, but still a majority of the audience is white.”

St. Louis-based singer and guitarist Marquise Knox, who opened for ZZ Top and Cheap Trick on a recent tour, has seen the same dynamic in the blues business, where most of the leading indie labels who specialize and support the music, like Alligator and Blind Pig, are not Black-owned. “We’ve got a lot of white people in control of the music, and nothing wrong with that,” Knox says. “But these are generally people who say they love us, that they care about us and have respect for us. Then they get ready to book these festivals, and even if they hire us, it’s maybe three of us. And we’re going to be the ones that kick off the festival at 12 o’clock, one o’clock, three o’clock.”

“People say they love us, that they care about us and respect us. Then they book these festivals, and even if they hire us, it’s maybe three of us. And we’re the ones that kick off the festival at 12 o’clock.” — Marquise Knox

Nichols, Knox, and their peers aren’t just trying to kick-start the blues; they want to reclaim the genre, to have it tell more Black stories. “The genre is dominated by nothing but, you know, Caucasian people,” says Ingram, 23. “The festivals, the organizers, the record labels — everybody’s Caucasian. I hate to put it like this, but when you don’t have people who look like you running the show, that’s pretty much how it’s going to be.”

Their quest raises many fascinating and difficult questions. In 2022, how can the blues connect to young music fans of all backgrounds raised on hip-hop and pop music? In that context, where even a guitar solo can be seen as an archaic convention, what’s the future of the blues?

“I’ve seen so much diversity in my short career as a blues man,” says Nichols. “Even as a casual listener, I was so used to being the only Black person in a room. But then once I started creating my own space as an artist, I saw so many more people coming in — people who don’t identify as blues fans. There’s the fan base that the music industry markets to make money, and there’s the fan base of everybody else. That ‘everybody else’ fan base is a lot more diverse than people realize.”

In itself, Nichols’ journey to the blues is revealing. Born in 1991, he says the first music he remembers hearing was ‘NSync and Hanson, and even though he started noodling on his older sister’s guitar around 11 or 12, he spent his teen years searching for a direction. He played guitar in hip-hop bands, bought a turntable, dreamed of becoming a DJ, and formed a grindcore band called Concrete Horizon.

When he began dipping into his mother’s record collection, Nichols found CDs by artists like Cray and B.B. King, and Strong Persuader, Cray’s 1986 breakthrough album, stood out. “I thought, ‘Okay, this is called the blues?’” he recalls. “I really liked and still like Robert’s voice, and it was the first time I heard these lyrical guitar solos. I was able to imitate that pretty quickly.”

His interest in other forms of guitar music blossomed when he spent time with friends in Milwaukee’s West African community, who introduced him to artists like Ali Farka Touré, the late Malian guitarist and singer. “That put me on the journey of really understanding what folk music and cultural roots music are,” he says. “I saw what it meant to these people, and I felt this connection to it. But I also felt like there was something from my own culture that I needed to go back and connect to as well.”

Nichols, who started using the “Buffalo” moniker for some of his projects but also went by Carl, moved into folk and Americana, spending a few years in the Milwaukee duo Nickel & Rose with bassist Johanna Rose. The group cut some indie records, but Nichols soon grew disillusioned — a sentiment that roared out in a song, “Americana,” that addressed why he felt so out of place in that genre. “If I wasn’t standing on this stage, would you wonder why I was here?/Would you ask me if I was lost or if I came to sell you pills?” he sang. As he says now, “It sounds stupid to say it, but it’s not a song I wanted to write. But I had to write that song. At the time, I was just like, ‘Why can’t I just be comfortable in these places?’”

That point was rammed home not long after, when Nickel & Rose played a logging festival in Wisconsin and saw a Confederate flag on display from one concertgoer. “The reaction from not everybody, but from most people was, ‘What’s the big deal?’” he says. “We said, ‘This is the point: You’ve created a space where you don’t expect anybody who’s not white to ever come, and then when somebody does and says, ‘Hey, this is a problem,’ you don’t understand the problem because you’ve never considered the experience or the thoughts of anybody else. That was the broken record of Americana.”

Christone “Kingfish” Ingram (Photo: Justin Hardiman)

The lack of support Nichols felt from his own music community led to him moving away from Americana. Playing solo gigs at local hotels, he began refining a new style, which led to a deal with Fat Possum, the Mississippi-based label. “Every once in a while, somebody cuts through it all, someone who makes everyone listen when they’re singing in a bar,” says Fat Possum cofounder Matthew Johnson. “He’s a huge disrupter, and that’s always good. It’s what you’re looking for.”

Fat Possum established itself three decades ago by signing unjustly forgotten blues legends like R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough before it went on to work with the Black Keys, Soccer Mommy, and other non-blues and indie acts. According to Johnson, Buffalo Nichols is the first blues album the label has released in about 20 years.

Does he regret not signing more Black blues artists in the interim? “I wish we had,” Johnson says candidly. “It felt like the genre was hijacked and going in a direction we weren’t excited about. It became this bullshit of how fast you could play your scales. What the fuck happened?”

What did happen? The blues may have originated in the Mississippi Delta, but its rediscovery by white blues fans and musicians in the Sixties changed everything, as volumes of scholarly research since then have explored. Some of those kids formed their own bands to honor (some would say mimic) the blues, and white blues quickly became a hugely popular genre with a fanbase to match. Today, that’s led to an industry that seems more eager to promote the Black Keys’ R.L. Burnside covers than, say, a striking album by his grandson Cedric Burnside.

Nichols sees the current problem as two-pronged: making the blues relevant to a new generation of fans, and also convincing more young Black musicians to play this music in the first place. “The first step is representation,” he says. “The first time you see people who look like you making music, chances are that’s what you gravitate to.”

Some creators hope that topical songwriting can make the genre connect with listeners who don’t gravitate toward blues guitar solos — and who may be finding the longstanding artistic power of the blues expressed elsewhere. “Black people got more blues right now than we had 100 years ago,” says Knox. “A hundred years ago, they didn’t say, ‘Black folk won’t have a net zero in the bank.’ That wasn’t the forecast. But this is the forecast now. How do we talk about this? This is the blues’ problem. It is not ready to be as revolutionary as hip-hop, R&B, neo-soul, and all these communities.”

Ingram, for one, takes exception to the idea that young Black blues artists are few and far between. “The Black representation could be better,” he says. “It could always be better. But that’s one of the biggest problems I have. They try to paint a picture that young Black kids are only into what’s urban, but there are some of us out here who love the traditional style of music and want to keep it going.” Others in the blues world point to a slew of traditional-minded up-and comers, like guitarist and singer Melody Angel, blues-sax player Vanessa Collier, blazing guitarist Selwyn Birchwood, country-blues-rooted Jontavious Willis, and Memphissippi Sounds, a raw duo out of Memphis featuring Damion “Yella P” Pearson and Cameron Kimbrough, grandson of Junior. They join the likes of Adia Victoria and Amythyst Kiah, to name two acclaimed artists who are modernizing the genre by way of more contemporary arrangements while adhering to many of blues’ tenets.

One of the highlights on Nichols’ album is “Another Man,” inspired by the traditional Black spiritual “Another Man Gone Down.” Knox’s “You or Me” was fueled by the murder of George Floyd (“I know you seen the cops kill that man in the streets/I’m warning you, one day that could be you or me”). Ingram wrote “Another Life Goes By,” from his Grammy-nominated sophomore album 662, in 2019, thinking about the killings of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. By the time Ingram recorded it, Floyd was dead and the song took on another context.

Much like Clark Jr. has on his recent records, Ingram blends classic Delta lead guitar with tasteful electronic percussion to make the song extra contemporary. “If you look at the musical aspect of the song, we use beat programing and everything,” he says. “And even what the song is talking about — killings of unarmed Black and brown people — all of that is the blues. A lot of people forget blues was protest music. That’s we’re trying to do in this age. We have to bring that into 2022. I try to add a little bit of urban flavor to my blues. Then you can teach them about the raw, original thing.”

Veteran blues hero Taj Mahal, who’s been supportive of many upstarts over the years, saw for himself when he and Ingram both played on one of Naber’s blues cruises. “Incredible musicianship,” Mahal says. “An incredible vocalist. He’s unafraid to take some of the contemporary stuff and put it in the blues form.”

Ingram himself opened a dozen or so shows for Vampire Weekend, even joining them onstage a few times to jam on Neil Young’s “Vampire Blues.” “Each night was kind of nerve-wracking for me,” Ingram admits, “because anytime you try to bring blues to that age group, they might run away. But honestly, the response kind of surprised me. I was getting messages from kids who attended shows: ‘I wasn’t really into blues at first. But after seeing you play with the Vampire Weekend guys, I’m into it.’”

Encouraging millennials and Gen Z fans to give the blues a chance is another, separate challenge. “Young people need to see younger people playing the Blues,” says the Blues Foundation’s Judith Black. “I don’t know how many of them have actually had the chance to see younger blues artists, right? So giving them the the visuals will go a long way toward getting them interested.”

The foundation that she runs has a scholarship program in which they pay kids to attend blues camps around the country, and the non-profit Blues Kids Foundation holds annual Fernando Jones blues summer camps, where students as young as eight or nine years old hone their chops. The annual Chicago Blues Festival, taking place this June, will feature many free outdoor concerts to pull in potential new fans.

From Rolling Stone US