When I was researching my latest book, which celebrates the Australian pop scene of the Eighties, it quickly became apparent there were bands who were remembering the decade not for the success it brought them, but for the lack of it.

For every Crowded House or Midnight Oil, whose careers transcended the Eighties and saw them become Hall of Fame rock royalty and respected names in the States, there were also the bands who imploded before the decade was out. America was the holy grail for them all, but poor management, bad song choices, excessive record company spending and personnel fallouts meant that these bands became casualties of the decade.

“I called him a cunt,” came the brash statement from British music mogul Simon Napier-Bell at his 2023 Bigsound keynote.

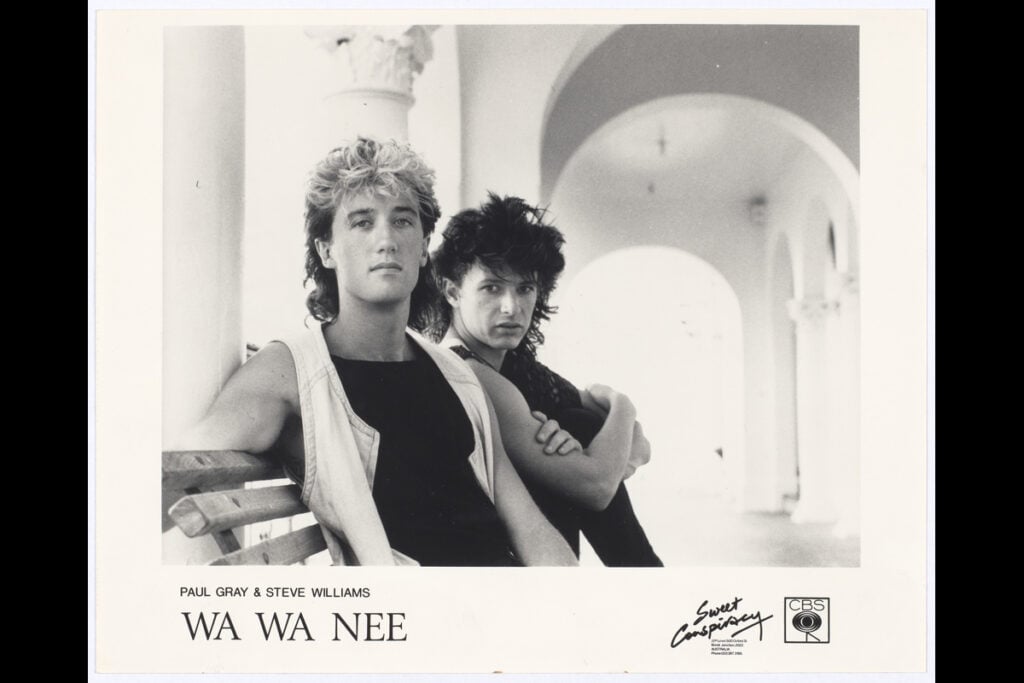

Napier-Bell was talking candidly about his time managing Australian band Wa Wa Nee in the late 1980s, and the person on the receiving end of the insult was the lead singer of the group, Paul Gray.

Napier-Bell was furious with Gray because he had declined to go to dinner with the head of their American record label. CBS had taken a punt on the Sydneysiders and were working towards a US Number One on the Billboard chart with their 1986 single, “Sugar Free”, which had already gone Top 10 in Australia.

The dinner refusal led to the band being dropped by CBS America and eventually led to Napier-Bell, a manager who had steered the careers of Sinead O’Connor, Jimmy Page and George Michael, parting ways with Wa Wa Nee.

Wa Wa Nee

In the 1980s, the United States was the ultimate destination for any band looking to expand their reach overseas. Australian artists Helen Reddy and Little River Band had already proved in the Seventies that chart success in America meant not only financial rewards, but a certain kind of validation and prestige that came with conquering the world’s biggest Western market.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Men at Work’s remarkable rise from Melbourne’s Cricketers Arms hotel to playing countless American stadiums and winning Grammys was the blueprint by which INXS and Crowded House would use to triumph on their US trajectory.

But for the few Aussie bands who found US success, there were even more who hit a brick wall, like Wa Wa Nee — whose chances were scuppered forever over that dinner invitation.

“The record company were working hard to make it happen for them,” stated Napier-Bell at Bigsound. “The first week, ‘Sugar Free’ went into the US charts at Number 91, the second week it was sitting at Number 49, then Number 35. We did some gigs, everything went brilliantly and then I had a meeting with Al Teller who was head of Epic and he said, ‘If everything goes well, we’re going to put Wa Wa Nee in to the Top 20 next week, and in three weeks you should be Number One, or at least in the Top Five.

“‘Also, tomorrow night I’d like to take you and Paul to dinner with my wife. My wife quite likes their music’.”

Paul Gray refused point blank.

“I’m an artist, I’m not a piece of meat,” he replied.

“It’s only dinner,” Napier-Bell reasoned. ”Be nice to the wife for a couple of hours, then you can go home to Australia knowing your record will be in the Top Ten.”

“N-O! Tell them I’m not well.”

It was here Simon dropped the c-word out of sheer frustration.

“You cunt.”

Napier-Bell couldn’t lie to Al Teller. He told the head honcho the truth.

The next week, ‘Sugar Free’ had slid back down to Number 41 and continued to fall out of the Billboard charts.

“Once Paul had dissed the CEO’s wife, the Americans couldn’t wait to be rid of us,” reflects Napier-Bell.

CBS America sent a directive to former Sony Music Australia CEO, Dennis Handlin, to “Stop sending us those silly Australian bands.”

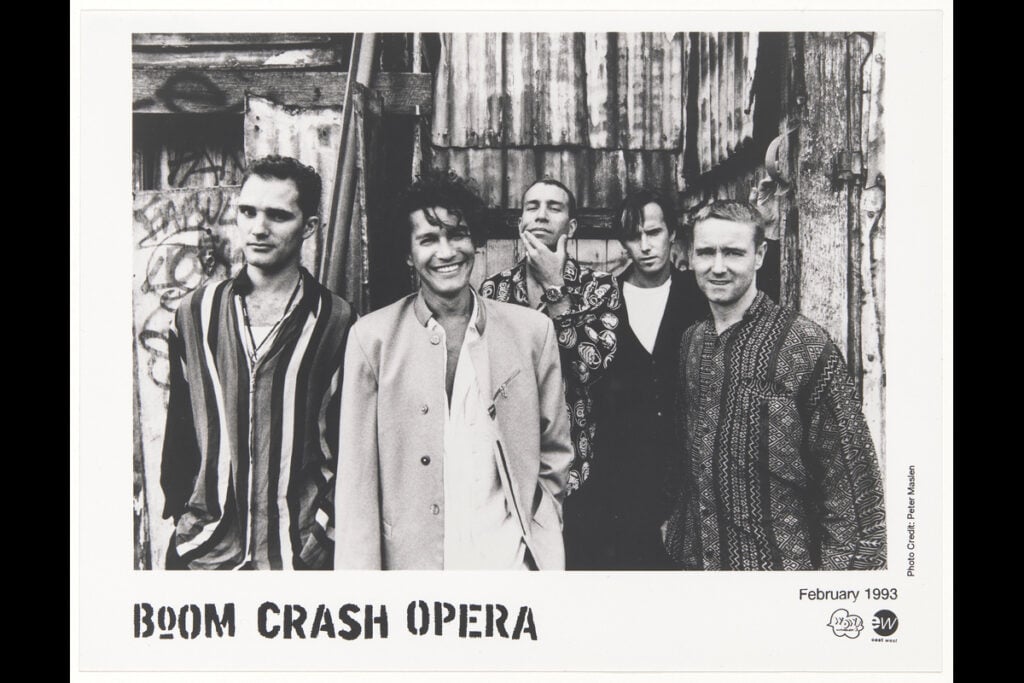

Boom Crash Opera

However, it wasn’t just about insulting the boss’s wife. Sometimes having a prominent American in your corner could actually have the opposite effect, as was the case with Melbourne band Boom Crash Opera.

The group were at the height of their commercial success in Australia, having gone gold with their ‘87 self-titled album, when U2 rocked up to their Sydney show with Rattle and Hum producer, Jimmy Iovine.

“Suddenly Jimmy says he wants to produce our next single,” says BCO guitarist Peter Farnan.

Farnan and the band explained to the super producer, (also responsible for Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell and Patti Smith’s Easter), that their 1989 album These Here Are Crazy Times! was already recorded and due for release in less than a month. They had also spent their entire budget.

Iovine offered to do two songs for free, believing he could help break the band in America. They flew to LA, and while Jimmy didn’t charge for his services, the recording studio and other hired hands did. It ended up costing them close to $100,000 and they came away with reworked Iovine versions of “The Best Thing” and what would become the fifth and final single from These Here Are Crazy Times!, “Talk About It”.

Meanwhile the first single off the album, “Onion Skin”, which Iovine didn’t produce, was blowing up on US college radio and peaked at Number Five on the alternative charts.

“It was really happening for us,” confirms Farnan. “We were ready to tour the US on the strength of that song, but then our management told us to hold off until the follow-up single, ‘Talk About It’ was released — a track that Jimmy produced. When that didn’t click, our whole US tour was blown out with just two days’ notice. I got the call as I was packing my bags and it pretty much broke all of our hearts.”

Farnan isn’t sure why the Iovine produced song didn’t work in America, where it should have, considering the pedigree of the name attached to it, but it could be because Iovine “over-produced” the song to the point that it didn’t sound like Boom Crash Opera anymore.

They attempted a second time, by engaging R.E.M. and Hootie & the Blowfish producer Don Gehman for their 1993 album, Fabulous Beast.

However, their time in the studio for that album also coincided with the 1992 LA riots. The entire place was on high alert and the band witnessed guns and mayhem in the vicinity of Hollywood. It wasn’t a conducive environment to create a record and they decided to get out as quickly as possible.

Fabulous Beast staggered into the Australian Top 20 in April 1993 and was never released in the US.

For BCO guitarist Richard Pleasance, the Eighties reminds him of excess. “It was just crazy the amount of money record labels were spending on producers, music videos and travelling. There was an ethos that if the producer was American then the album would be better, and the band had a better chance at breaking into the market, but that just wasn’t the case. They were just more expensive, and bands ended up owing a lot of money to their record labels… I still cannot believe how much we spent trying to make it.”

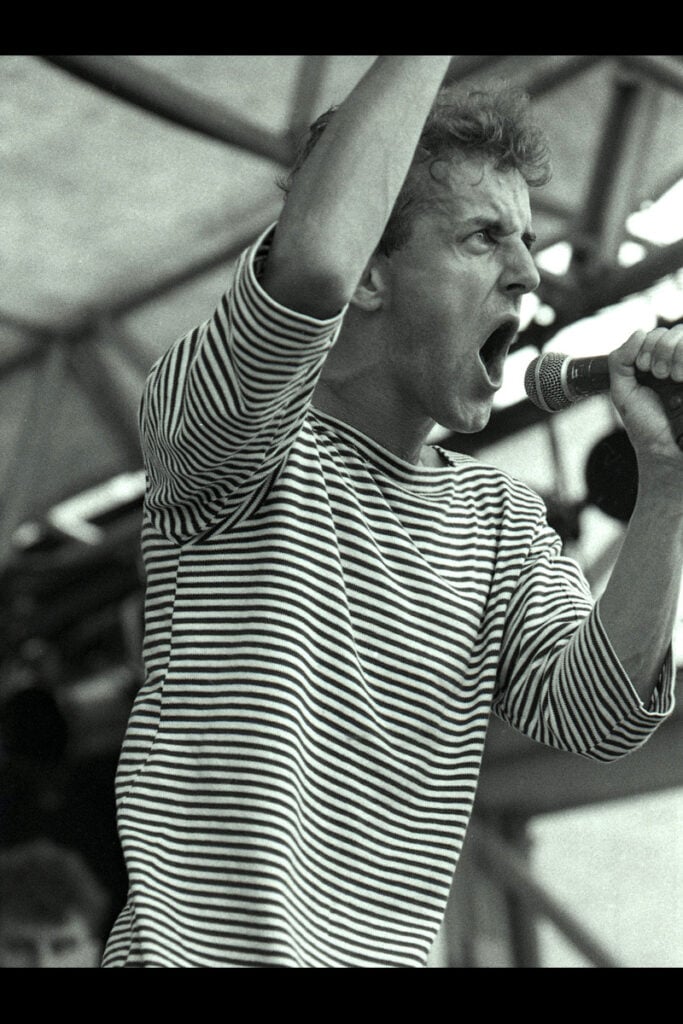

Machinations’ Fred Loneragan

Sydney band Machinations did enjoy some American success with their debut album Esteem (1983) which had been released through A&M Records in the US. Lead single, “Pressure Sway”, was doing great things on the college and dance charts.

“We couldn’t actually afford to go to America to maximise on this club and chart success,” says lead singer Fred Loneragan.

“So we sent our keyboardist over on a guest DJ jaunt which in hindsight probably wasn’t the best move, but we had no budget. He did some club and radio spots which went OK, but thankfully by then CBS America had expressed interest in us.”

Machinations had appeared on the movie soundtrack to Ruthless People with their single “No Say In It”; the soundtrack also featured Mick Jagger and Bruce Springsteen.

“Tommy Mottola [the then-head of CBS] wanted to sign us to one of the smaller CBS labels,” remembers Loneragan. “We were supposed to be going over to do a tour supporting Robert Palmer and we rang Tommy Mottola and he told us he couldn’t talk to us because his phone was tapped. This was around the time Sony were involved in a payola scandal. We didn’t hear from him for about six weeks — the label he was going to sign us to folded and everything went dead. We were so close!”

It was the same scenario for Kids in the Kitchen, an almost Duran Duran-esque Melbourne band who were tipped for big things when their debut album Shine (1985) peaked in the ARIA Top 10 and went platinum. Lead singer Scott Carne was only 19 years old at the time.

“We got signed to Sire Records in the States [they were noticed by the legendary Seymour Stein, who had already signed the Ramones and Madonna] and did a few showcases over there, but we couldn’t seem to get it happening in terms of good support slots or similar over there in the States,” Carne says.

“I think [Michael] Gudinski was worried about us jetting off because we were making good money for him here! The American label wanted to repackage us, change the line-up and get us writing with different people. Basically, mould us away from what we were and what we had achieved in Australia.

“It caused a rift within the band. Our manager sacked our drummer, saying we could get a better drummer over there. It was a terrible thing to happen to him and to us. I should have stepped up and said something but I was young and caught up with it all. That’s the regretful part.”

Kids in the Kitchen broke up in 1988 after their record company Mushroom insisted the band use American producers David Kershenbaum (Supertramp, Tracy Chapman) and Richard Gottehrer (The Go-Go’s) for their follow-up record Terrain (1987).

“We could’ve basically produced the album ourselves and probably done an equally good or better job, but unfortunately record companies want names of producers on the album and they end up just being really average.”

Kids in the Kitchen

For Melbourne band Real Life, they were one of the few who had overseas label support — they just couldn’t get any at home. Real Life shot to fame in 1983 with their homegrown hit, “Send Me an Angel”, which went to Number One in Germany and New Zealand, Top 10 in Australia and cracked the Top 40 in the US.

In 1986, the band recorded an anti-war song called “Babies” for their German and US record labels. While still synth-heavy, “Babies” sounded harder edged than previous Real Life output, breaking them out of the light pop mould and away from the ‘one hit wonder’ shackles of “Send Me An Angel”.

US commercial radio station KROQ placed the song on high rotation, which was a big deal for an Aussie band and it gained decent traction.

Their Australian record company BMG, however, refused to release the song locally, citing the lyrics, “We are bleeding babies” as offensive.

Lead singer David Sterry couldn’t believe it.

“That was the beginning of the end for me,” says Sterry. “What Australian label wouldn’t want to release a song that is screaming up the KROQ charts in the States? And we were fighting to get a new record deal with BMG. I still felt I had songs in me and that we weren’t just ‘Send Me An Angel Part 2’.”

In a bizarre turn of events, an American country music label called Curb re-released Real Life’s one and only global pop hit as “Send Me an Angel ‘89”, and remarkably, six years later, it surpassed its original US chart position and peaked at Number 26 in August 1989. It also went Top Five on the US Billboard dance charts.

So much for shaking off the ghosts of the past. While Real Life continued to produce music and maintain a following, the unique combination of factors that made “Send Me an Angel” a hit in the Eighties resulted in the band never surpassing the success of that iconic song.

Hodoo Gurus

Similarly for the Hoodoo Gurus, their American record label Elektra had grand plans in 1987 which fell flat over a song choice.

The label wanted to release “Good Times” because it featured US girl rockers the Bangles on backing vocals, who were hot property at the time. “Walk Like an Egyptian” had been a worldwide Number One and Elektra were keen to capitalise.

“We had originally thought of ‘Good Times’ as a B-side,” says Gurus’ frontman Dave Faulkner. “But the song was so good that as soon as the Bangles put their voice on it, we knew we couldn’t leave it off the record because it was so amazing.”

According to Faulkner, that’s where the problems started.

“The label was like, ‘Aha, here’s our chance to break this Aussie band in America. We’ve got this successful pop act on their song and they can ride on their coattails and get on the charts.”

The Gurus were dead against it. “Good Times” was a fun song, but hardly a single and certainly not one that the band felt was their strongest from 1987 album Blow Your Cool! to launch them in the States.

“We said, ‘But what about “What’s My Scene”? It’s done really well in Australia’, but they said that it was better suited for college and alternative radio. They kept telling us that we didn’t know their market and we tried our best to persuade them otherwise, but they wouldn’t be swayed.”

Faulkner remembers pleading with the heads at Elektra to change their minds.

“We begged. They literally said this to us: ‘Don’t stop us having this hit. We know what we’re doing. We can do this’.”

The record company got their way and, unsurprisingly, “Good Times” was a flop. It was a false start for the band who couldn’t crossover from the US alternative to the mainstream charts, despite releasing several albums in the US.

“Our worry was that people would hear ‘Good Times’ and not understand the rest of our music because it was a bit of a leftfield song for The Gurus,” states Faulkner.

“‘What’s My Scene’ kind of got shuffled away and never got its chance to really be pushed to real radio over there, which was a crime in my opinion. So that’s what happened. But, then of course afterwards they said, ‘Oh, I guess the public weren’t ready for it’. You know, it was never their fault, it was our fault all along but I do think about what American success could have led to.”

Manager Simon Napier-Bell never held what happened in America against Wa Wa Nee or Paul Gray, who sadly passed away from cancer in 2018.

“You couldn’t really fault Paul. He was principled and stuck with what he believed in. His life was about music, not PR,” he says.

Napier-Bell did manage to get the band to Italy and other parts of Europe, but it was evident that without the support of CBS America, the rest of the world wasn’t going to happen for them. He parted ways with the group and took on German disco group Boney M., who were enjoying a resurgence.

“For me — for the rest of the band, for Paul too — it was just one more rock ’n’ roll experience.

“Sometimes, especially in the 1980s, that’s just how things worked out.”

I HEAR MOTION: THE BANDS WHO SOUNDTRACKED OUR LIVES 1980-1989 by Jane Gazzo is out now through Melbourne Books.

This article features in the September-November 2024 issue of Rolling Stone AU/NZ.

Whether you’re a fan of music, you’re a supporter of the local music scene, or you enjoy the thrill of print and long form journalism, then Rolling Stone AU/NZ is exactly what you need. Click the link below for more information regarding a magazine subscription.