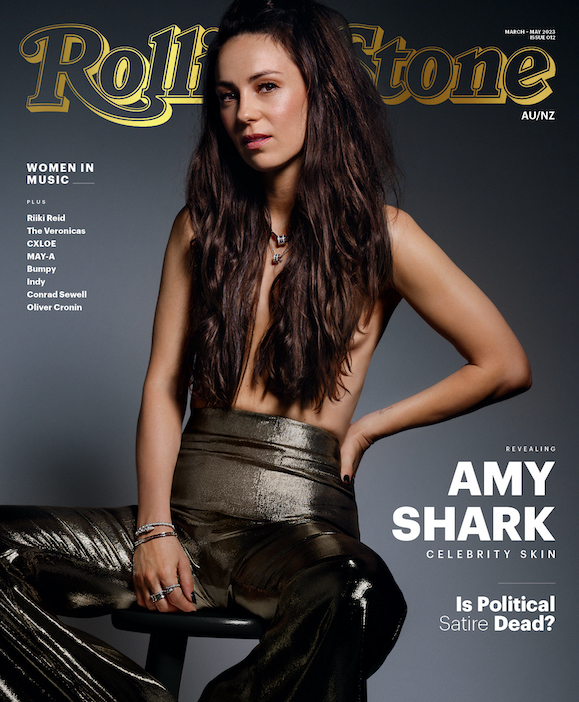

Photo by Michelle Grace Hunder

Amy Shark’s Celebrity Skin: The Rolling Stone Cover Story

A thick skin is necessary for the current Amy Shark era. She’s exploring new waters, both sonically and personally, and it seems she’s ready to plunge into greater depths, writes Poppy Reid.

A young woman in black heels and a corporate-grey pencil skirt rushes to her fridge. Pulling out a frozen meal, she looks exasperated as she melts off the crusted ice with a hairdryer.

The YouFoodz commercial from 2015 is convincing; you can picture this character’s long day at her desk job, and how she missed her lunch break when she got called into a meeting. What you may not fully understand is the actress behind the character: an equally exasperated aspiring musician.

Seven years ago Amy Cushway (as she was then known) was a novice thespian, taking odd acting gigs between working her own nine-to-five as a video editor for rugby league team the Gold Coast Titans. As a teenager, she was awarded Outstanding Actor two years in a row at her high school drama festival. “I’ve still got the goblets to prove it,” she chuckles, as we have lunch in her Gold Coast hometown. “And they’re still stained from all the Passion Pop I drank out of them in the park after I won them.”

Fast forward to 2015 and she’s performing covers at pubs across Queensland, almost ready to give up on music altogether. That part of her story is widely known: how her now-husband Shane secretly applied for the grant which led to the recording of breakout hit “Adore”; how he believed in her, wouldn’t let her give up, and eventually ditched his own career as a Chief Financial Officer to manage her full time. But Amy has told that widely-publicised story already, so when her team schedules several one-on-one days of interview time for us it seems she’s ready to plunge deeper than she’s ever been.

Zooming out to capture everything that Amy’s involved in, you might think it would be overwhelming for one person. She’s an investor in beer brewing company Fields Brewing, she’s a judge on Australian Idol, she’s drip-feeding singles and music videos from an album she’s still creating, she’s relentlessly touring (in 2022 she performed seventy-four shows), travelling, and nurturing friendships, her marriage, business relationships, and creative partnerships… Even acting is still on the cards; she turned down a movie late last year. It’s enough to exhaust even the most seasoned pop star. And yet, she has an ease about her.

The waiter at Rick Shores has us seated at what he calls the “rock star table”. With an uninterrupted view of Burleigh Beach, it’s so close you can hear the waves crashing in front of us. Over two beers and the kind of seafood you do write home about, Amy is telling me she “doesn’t give a fuck anymore”.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“I’m not sad anymore,” she says, referring to her first two number one albums Love Monster (2020) and Cry Forever (2022). “And even if some songs are sad, I’m okay with it. It’s not going to take me over like some of the other songs did.”

Tracks like “Amy Shark” and “Baby Steps” — which weave in details of her estranged relationship with her father — were tough to write and tough to promote. Naturally, her father reached out after hearing the lyrics to “Amy Shark”: “And I did it all without a phone call / Or a Christmas card / You have no heart”. But Amy is the type of person to put certain people in a locked box, and bury it deep in her mind, if she needs to. You’re packed away and gathering dust. Forgotten.

“I did it with my dad,” she admits. “It’s like bro, you can email me all you want. It just doesn’t affect me. It’s gone. […] And you know what, it’s so ‘in a box’ that I’m now like, ‘Poor guy. Hope he’s alright, wherever he is’.”

A thick skin is needed for Amy Shark’s current era. Though far and away her biggest commercial achievements are nine multi-Platinum singles, and over thirty award wins including a Rolling Stone Australia Award, eight ARIAs, and four APRA songwriting awards, her spot next to Meghan Trainer and Harry Connick Jr. on the Australian Idol judging panel places her in living rooms across the country for eight weeks. But unlike its predecessors, the reveal of the Idol judges faced backlash over its glaring whiteness. The show was lambasted on social media until producers announced Idol judge alumni Marcia Hines had joined the fold as a guest judge. It’s understood none of the judges knew the full judging panel lineup until the day of announce.

The move to mainstream television kicked off last year when Amy Sharkjoined Celebrity Apprentice, a reality competition series where she joined stars like actor Vince Colosimo and NRL player Benji Marshall to take on challenges and raise money for charity. Amy raised $20,000 for music industry charity Support Act.

Amy Shark, photographed on December 6, 2022 at Work Horse Studios in Sydney by Michelle Grace Hunder. Creative: Katie Taylor. Stylist: Jana Bartolo. Hair and Makeup: Sara Tammer. Production: Long Story Short. Photography Assistant: Jade Florence Mulvaney. Styling Assistant: Kirsten Humphreys. Styling Intern: Yasemin Onur.

The rapidly expanding world of Amy Shark, outside of just music, was initially a challenge for someone who doesn’t court the limelight. Until recently, Amy struggled with the material and immaterial consequences of fame. From being recognised and idolised (the waiter at lunch said he was “privileged” to be serving us) to the new waterfront home, and the full team of staff who work for her, she attached guilt to her success. She believes the guilt was partly thrust upon her from a modest childhood growing up with her mum, stepdad and half-brother, and partly due to Australia’s tall poppy syndrome, which dismisses those who dare to dream big and get paid accordingly. Now, she leans into it unapologetically and refuses to mute her successes.

“I don’t know what’s happened but I just don’t give a fuck,” she flashes a cheeky smile. Amy, who had long been embarrassed about her wealth and success, comes from a family where these things have never been seen as important.

“To the point where — and I’m not bagging my parents, but they walked into my [new] house and were like, ‘Oh, la-de-dah’. You know what I mean? ‘It’s a lot to clean’.

“[…] That used to really hurt me. And my parents don’t know…” she pauses, “I don’t think they go out to hurt me at all. But that’s who they are. And I used to really struggle with that. Whereas now, I’m proud of it. I’m not embarrassed by doing well or buying a big house or having shit. Or being on TV, or doing weird things.”

“I don’t know what’s happened but I just don’t give a fuck.”

Walking into Amy Shark’s Gold Coast home is, at first, like walking into a show home. “We’re renovating,” she clarifies, giving me the tour.

From the freshly polished floor tiles, the still-to-be-hung portrait of Amy Winehouse, the pristine carpet on the second level, and a scattering of belongings still packed in boxes (including a stack of record plaques filling an entire guest bathroom), the house feels largely unlived in. That’s because it is. Amy Shark completed the biggest local tour of any Australian artist last year when she took the See U Somewhere tour on the road for sixty dates. She slept in buses and hotel rooms for four months and when she wasn’t touring she was in studios dotted across the globe. At the time of writing, she’s rusticated in a cottage with producer Dann Hume at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios in South West England. She doesn’t stop, she’s a global force, and she has no plans to slow down.

There are two rooms in the house that feel very ‘Amy’. Her home studio, and the bedroom — complete with a walk-in robe (where clothes are colour-coded), and motorised blackout curtains. “Watch this,” she says as she hits the button to darken the room. “This is my favourite thing about this room.”

Above the bed is a large print of Carrie Fisher laughing at the beach, in costume as the tough heroine from Star Wars, Princess Leia. “Is Shane a fan?” I ask. “No, that’s me,” she smiles.

In the closet I notice a pair of black and white Alexander McQueen boots, proudly on display but never worn. “They’re Shane’s,” she says. “They’re a gift from Russell Crowe for [Shane’s] birthday.” She’s laughing now at the polarity between how ostentatious the gift is from a Hollywood magnate and how unassuming of a person her husband is — as if she can’t quite believe their life sometimes.

Clearly her main priority and most-used space in the house, the studio features no less than nine guitars, a Nord Stage 3 Compact keyboard, a sound desk, and a blue velvet couch.

Amy heads to the computer to play me a few tracks she’s been working on, but as soon as she logs on, the call-to-arms charge of Reclaim Australia by hip hop duo A.B. Original starts blasting. “He’s probably one of the main people I text,” she shrugs, referring to one half of the duo, Briggs. “We both have a very dry sense of humour.”

A pop artist who listens to political-activist hip hop and opts for baggy T-shirts and Ugg slides, Amy is not interested in peddling female pop artist stereotypes — even during her hosting duties on Australian Idol Amy rocks baggy Gucci shorts and flats.

Amy Shark may have come into the industry as an outsider — just listen to the lyrics of “I Said Hi” for an insight into how gatekeepers ignored her until the cries from fans were too loud to ignore — but no one can pull the wool over her eyes. She’s been charging through the music industry, slowly changing the rules for female pop acts by playing the game she has to and also making up some rules of her own. She’s aware, more than most, of the importance of reinvention as a female artist. It’s why she donned a platinum-blonde wig for the “Only Wanna Be With You” music video and single promotion (and swiftly ditched it when she realised she’d be sitting next to blonde bombshell Meghan Trainer on Australian Idol).

She plays the “Only Wanna Be With You” video on her screen and sits next to me on the blue velvet couch, hiding her face and giggling behind her hands. “It’s cringe for me to watch,” she says, peeking through her fingers as Blonde Amy dances on-screen.

That first taste of album number three has clocked millions of streams, and kicked off Amy’s current fun, up-tempo songwriting era. Written with US songwriters Joe London and Grant Averill in LA, the song was sparked by a chance interaction with an ex-boyfriend at a corporate gig.

“He’s had a few beers, so he’s all relaxed,” she recounts. “So we got through all the bullshit about your life, ‘Congratulations’…,” she wafts her hand in the air as if to say ‘et cetera’. “And then he was like, ‘What happened with us?’

“I was like, ‘Oh I’m not doing this! I’m not. Not here, right now. Like dissecting a fucking relationship I was in five hundred years ago,” she grins awkwardly as the memory rushes back. “I can’t… This can’t be happening.”

On the plane home Amy let the situation marinate, how this man was a great catch, but in truth, was a distraction from the person she wanted (but who was taken at the time); her now husband Shane.

“He really was a really nice guy, a good looking dude. And I turbo-dated for so long because I couldn’t be with the person who I wanted to be with. So, I dragged him on,” she says, wrinkling her nose. “I dragged him on a lot.”

When I meet with Amy at producer Konstantin Kersting’s Brisbane studio, they’re finalising the vocals on “Only Wanna Be With You”. Amy has ditched the trademark top-knot, something I’m told she does when she prefers not be recognised. She’s without makeup, of course, and is dressed in blue jeans, a cut-off The Cure singlet layered over a white T-shirt, and brown Birkenstock sandals with grey socks. Jumping into the vocal booth, she experiments with some lyrical variations before finding the inflection she likes.

“Yeah sick. Let’s just do a couple of those,” says Kersting from the desk.

His hands move at lightning speed to re-configure the track, his bright green nail polish a fluorescent neon blur. He plays it back to Amy and she beams: “That’s a totally different bit now.”

At this point in March last year, seven months before the single was released, Amy and Kersting had been working on the new era of Amy Shark every weekday for a month. They were averaging four songs every five days, and Kersting mentions they’ve only revisited one song so far.

“Sometimes artists are scared of going in a certain direction,” he says, “because they have a preconceived idea of what their sound needs to be. Whereas Amy just came in and was like, ‘Let’s do whatever the fuck we want to do’.”

“We’ve tried a bunch of shit and nothing’s scared me,” Amy adds. She checks her phone and touches her stomach. “Should we go eat?”

In line for sushi nearby, Amy casually lets slip that she underwent surgery to treat a chronic condition. We’re just about to order and the restaurant is crowded; I remind myself to ask her about this later.

When Amy Shark first burst into public consciousness in 2017 with her debut EP Night Thinker, she had already spent years feeling locked out of its inner circle. She came into the industry as an outsider, knocking on its door and receiving lukewarm responses — as the industry is known to do. But then something changed. The fans chose Amy Shark as their own, they lifted “Adore” to the top of the charts, requested her music at every radio station and turned up to her gigs donning her signature top-knot hairstyle.

Amy has never held this against industry executives though. Instead, she uses her knowledge of the game to change it from the inside. She handles both worlds — the industry rat race and true fan connection — differently, but with the same hands. She can be the grin-and-bear-it pawn at the office showcase for puppeteers; but don’t think she’s not holding half the strings behind her back. She’s sitting in the boardroom meetings, she’s leading creative strategy discussions, and she’s pitching her next steps in order to unlock marketing budgets. Amy doesn’t know how to take a backseat — nor does she want to.

Perhaps this is why she still hasn’t spoken about what really happened at the 2018 ARIA Awards. According to The Australian, Denis Handlin, the fired former head of Sony Music Australia, left her “in tears” after she forgot to thank him during one of her three acceptance speeches.

Amy Shark, photographed on December 6, 2022 at Work Horse Studios in Sydney by Michelle Grace Hunder. Creative: Katie Taylor. Stylist: Jana Bartolo. Hair and Makeup: Sara Tammer. Production: Long Story Short. Photography Assistant: Jade Florence Mulvaney. Styling Assistant: Kirsten Humphreys. Styling Intern: Yasemin Onur.

Amy continues to play the long game, and even now, in the comfort of her home studio, tries to close the chapter. She’s visibly uneasy, and after an impulsive glance at the door (as if she’s checking her nearest exit), she deflects from how she became embroiled in the controversy surrounding Sony Music Australia.

“A lot has been said, not from me, but from others… which is disappointing. Some true, some not true,” she says lugubriously. “I remember the night as a night my music was celebrated. I worked incredibly hard on Love Monster, and the ARIAs were a time for me, my team, my label, my agents, my publishers, and my fans, to come together and enjoy, and be grateful for, what that album achieved.”

“A lot has been said, not from me, but from others… which is disappointing.”

Amy is driving us from her house to Glass Dining & Lounge Bar in Main Beach for lunch. It’s a nice change for Amy, who is usually the passenger: “Someone’s always putting me in a car. Whether it’s to get me somewhere or to get me the fuck out of somewhere.”

“Someone’s always putting me in a car. Whether it’s to get me somewhere or to get me the fuck out of somewhere.”

The chipping black paint on her fingernails glints in the November sunshine and I remember to ask her about the surgery she had.

Amy’s agony with endometriosis began in 2017, a year before she was diagnosed. She says the excruciating abdominal pain, which reaches levels of acute intensity around her period, is “unbearable”.

“If I didn’t have codeine I would die,” she says. “I’ve had breakdowns before. I’ve been at an airport and Shane will just see me rummaging through shit. Especially if we’re going international and I know I can’t get it. […] If I didn’t have those tablets, I would have to cancel shows. There’s no way I could stand up.”

Amy had excision surgery to remove endometriotic lesions from her body in 2019. Shortly after, she was onstage at Winton’s Way Out West Festival and found herself with a burst stitch at one of the surgery entry points.

“I didn’t even say anything,” she remembers. “Shane goes, ‘How do you feel?’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah, I think I’m good’. And I looked down and I was like, ‘Fuck, one of my stitches has popped out’. I didn’t tell anybody.”

At lunch Amy tells me about the author her and her friends love because of how “spicy” the writing is. She struggles to recall the author’s name and messages the group text thread she has with the girls she’s known since high school. One friend swiftly replies and she reads it out loud: “Verity by Colleen Hoover. It made me think I don’t give enough blow jobs.” Amy launches into a fit of laughter.

Later, two men who had been lazily sauntering along the marina pier decided to stop right behind our table. One man’s arse is millimetres from Amy’s head. From her seat she grabs onto the chair arms and turns around toward them. “Are you right?” she says with an agitated grimace.

‘A woman would never be so unaware of her surroundings,’ I think.

If music is a reflection of society, then it’s musicians who hold up the mirror. Amy may be a woman of definitive presence, but she is hyper aware of the gendered hurdles she must navigate as a woman in music.

“Dean Lewis and Vance Joy can look the exact same forever, and their music is enough. Women have to keep reinventing and reinventing and reinventing,” she says, irritated. “[…] I just wish I could have my same old brand forever, but you feel boring. You feel like people are bored with you.”

“Women have to keep reinventing and reinventing and reinventing,” says Amy Shark.

Amy reminds me of how Adele scrapped an entire album about motherhood when her manager told her it wouldn’t sell. As someone who might choose to have children one day, Amy is frustrated by the clear double standard for men and women in music.

“Kevin Parker’s got a kid [and people think] ‘That’s so cute. That’s so cool’. ‘Oh Matt Corby is a dad? That’s so cool’.

“‘Amy’s pregnant? Oh, she’s a bit unfuckable now’. That is the word. She’s just a little bit unfuckable and people can admit it or not. You can be like, ‘Yeah girl’ all you want. It does something in people’s minds that I don’t think they’ll ever be able to control.”

Amy had little support for her music ambitions growing up. Her mum and dad had her when they were just twenty and nineteen, respectively. Her now estranged father spent much of her life living in Canada and her mother isn’t exactly a sidestage stalwart. She did have one family cheerleader though, her grandmother.

“I would give my whole heart and soul for my nan,” Amy says. “I would do anything for her — and she’s built that. You’ve got to build things.”

Last year Amy skipped Australian music’s night of nights, the ARIA Awards, to sit on her nan’s couch and watch the TV broadcast. She was up for Best Australian Live Act, but with her nan’s carer overseas for a month, Amy stepped in to help for those four weeks.

If Amy’s nan is her biggest cheerleader, her husband Shane is her lodestar. She’s visibly more relaxed when he’s around, and he’s the creative sense-checker she values most.

“There have been so many times where I’ve worked my arse off on something. And he’s the only one whose opinion I really cared about,” Amy says.

Part of Amy and Shane’s secret sauce is the fact that he doesn’t ask about the exact inspirations behind her lyrics. It’s a fascinating dynamic, where her husband refuses to pry into something her fans actively dissect each time she releases a song.

“That’s why Shane and I work so well,” she says. “He just doesn’t have it in him to be like, ‘Is it about me?’”

“[…] I wasn’t just born and met Shane,” she clarifies. “We’ve worked really hard to become a very…” she pauses, “you know, what’s the word? Not a confident couple, but we’re not insecure.

“He knows that these stories are what has given us this life,” she adds. “He knows I’ve had my heart broken before. We’ve both dated other people, we’ve both had weird experiences.”

Amy Shark, photographed on December 6, 2022 at Work Horse Studios in Sydney by Michelle Grace Hunder. Creative: Katie Taylor. Stylist: Jana Bartolo. Hair and Makeup: Sara Tammer. Production: Long Story Short. Photography Assistant: Jade Florence Mulvaney. Styling Assistant: Kirsten Humphreys. Styling Intern: Yasemin Onur.

Amy dips into that sharp, biting humour that has resonated with so many Australians: “I can talk about the argument we had about our Superannuation fund, if you want. But I don’t know if that’s going to hit the charts.”

Sonically, the record doesn’t exactly pale against the indie-pop odysseys Amy has released in the past. But it doesn’t traverse old ground either; it’s unlike the dramatic indie-alt-rock blend of Love Monster or the sublime guitar-pop of Cry Forever. Instead, this developing record is Amy’s turbo-charged, richly literate line in the sand. It’s urgent, it’s belting, it’s fun, and it tells you to meet her at the bar.

The record has a warm blanket moment too. Amy hasn’t laid down the demo for the album track yet so grabs an acoustic guitar and plays a quick concert for one in her studio. “Beautiful Eyes” is a soul-stirring song about inner strength, with lyrics like: “Don’t hold back when your legs start moving/Try to react/Don’t think just do/Don’t let the days go by/Open your beautiful eyes.”

One track she plays from her audio files completes the triptych of blink-182 members Amy has now collaborated with. Following 2018’s “Psycho” featuring Mark Hoppus, 2020’s “C’mon” with Travis Barker, and now “Only Friend” with Tom Delonge, Amy is averaging a Blink collab every two years. Interestingly, the song was written in 2018 and was previously titled “Alien”. But with Delonge being closely watched by the US government due to his obsession with extraterrestrial life, the track title had to be changed.

“He was like, ‘Hey, can we change the hook so I can be on it?’ I’ll show you. It used to be ‘You’re the alien in the room’. And now it’s ‘You’re my only friend in the room’.”

Amy moves to her desk to play “Only Friend”. It’s about a person she dragged along to an event that’s not their scene. All signs suggest the track is about Shane, but in this moment, Amy would prefer to focus on the guitar riff.

“Just listen to this riff okay? I’ll play you a little bit of it, but just listen to this for a second.” The snappy, pop-punk guitar part plays. “Isn’t that sick?”

Amy Shark reveals another piece of her psyche with each record. The more albums she releases the more unapologetic she is, and the less she curtails herself. After almost a decade spent finding and honing her sound, she’s done with second-guessing and is now in her most experimental phase.

“I don’t care if it sounds dance-y and there’s some pop with a capital fucking P coming up. If that’s what the song wants, that’s what it’s going to get.

“[The album’s] got everything in it to possibly go ‘boom’. Who knows,” she shrugs. “You just never know. In my car it goes boom. That’s all that matters.”

If my days spent tailing her have taught me anything, it’s that there is no Amy Shark, the alter-ego, and Amy Billings the woman. The Amy that exits stage left after a blazing arena concert to take selfies in the carpark with fans is the same Amy tucked up in bed reading steamy psychological thriller Verity by Colleen Hoover. Amy Shark has been through the eye of the needle, personally, physically and professionally. However, she’s spent the last few years focusing on what matters most: family and music. In that order.

“When I’m here,” Amy Shark gestures to the four walls of her home studio, “nothing can hurt me.”

“When I’m here,” Amy gestures to the four walls of her home studio, “nothing can hurt me. And as long as I’m not going through some hectic divorce or my close friends don’t hate me; as long as my personal life is good, I don’t give a shit about anything else. Because they’re the only people that really matter.”

This Amy Shark interview features in the March 2023 issue of Rolling Stone AU/NZ. If you’re eager to get your hands on it, then now is the time to sign up for a subscription.

Whether you’re a fan of music, you’re a supporter of the local music scene, or you enjoy the thrill of print and long form journalism, then Rolling Stone Australia is exactly what you need. Click the link below for more information regarding a magazine subscription.