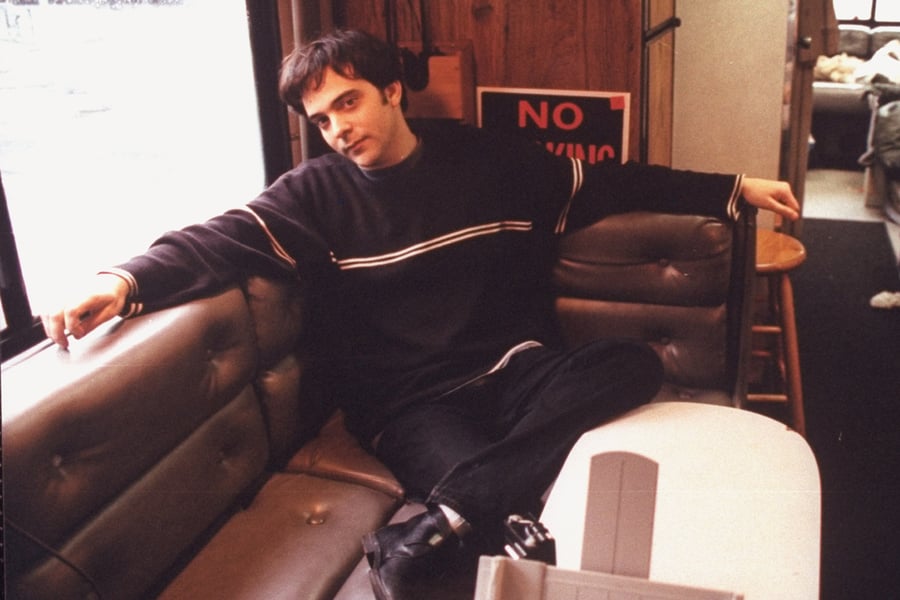

Since Fountains of Wayne co-founder Adam Schlesinger died of complications from COVID-19 on April 1st, tributes from his many friends and collaborators have poured in from all corners. Here, author and playwright David Bar Katz remembers their 35-year friendship.

There are songs we would all have known by heart that we’re never going to hear. There were going to be musicals we’d have waited in line to see that will never be composed. The expressions on my friend’s face that I was counting on to brighten the landscape of my future are now darkened by shadow; his light, relegated to the past, is now only cast from behind.

Like most of us, I thought the coronavirus only killed the old, or younger people with pre-existing conditions. Adam Schlesinger didn’t fall into either of those categories. But for as long as I’ve known Adam, he’s eluded categories.

We met in 1985 at Williams College, where we were placed in adjoining dorms. We immediately bonded over being Jews from similar areas, Philly and Jersey, who were now ensconced in WASP-y New England. While our fellow freshmen talked about Religion or Econ 101, we jokingly made our escape plan for when the inevitable pogroms arrived. Adam thought that I had the best shot at escaping because my years of prep school left me with a Brooks Brothers wardrobe that served as an excellent disguise that allowed me to “pass.” I said that Adam would actually be the one who survives: “They’ll keep you alive for your musical talent.”

“Great,” Adam said. “I’ll be like those Jews in the camps who were forced to play Mozart to Nazis.”

Our freshman year was in the pre-CD era, a time of cassettes and radio, so Adam immediately clocked the stacks of vinyl in my dorm room and dug in with an intense level of scrutiny. I realized he wasn’t just evaluating my music — it was as though he were reading my diary. Black Flag, The Specials and Yaz all received nods of approval, as did Gerry Mulligan, Mingus’s Pithecanthropus Erectus, and Make Way for Dionne Warwick. But there was only one album that Adam fully pulled out: the Police’s Reggatta de Blanc. The blue sleeve was worn to the point of being ragged, I’d played that album so often. Adam examined it closely. Then, with a severe look, he said, “You haven’t listened to this enough” — simultaneously conveying his critique of me and his adulation of the album. As we got to know each other I realized what a perfect Adam statement that was. He was totally serious. And it was a joke.

The name of his best-known band wasn’t dissimilar. Fountains of Wayne. It sounds mythical, encompassing the grandeur of nature, the power of water, and something somehow legendary. It was also a store in Jersey that sold the kind of fountains one would find on the lawn of a McMansion. Not to mention in front of Batman’s stately Wayne Manor.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

In college, Adam had a band called The Rhythm Method which played the big parties and mostly performed popular songs that they replicated perfectly. “Take On Me” and “Purple Rain” come to mind. I can still picture the half-amused, half-concerned look on Adam’s face as he played bass or keyboards or sang — a cross between someone simultaneously parodying a song, adoring the music, and being the anxious stage manager. I remember teasing him about the band’s name. I said, “The Rubbers or The Diaphragms would be more punk and sound cooler.”

“Yeah,” Adam said. “But the thing about The Rhythm Method is everybody knows it doesn’t work.”

***

Despite the coronavirus shutting down our world as it continues to rack up a sobering body count, many of us are still waiting for the other shoe to drop. Will it be as bad as they’re saying? Is the cure worse than the disease? Are we being overly cautious? When can we get back to normal life? As though this entire crisis is an inconvenient fire drill and we’re all impatiently waiting out in the cold for the experts to tell us the coast is clear so we can go back inside and return to business as usual.

For those of us who knew Adam personally, the virus is now worse than anything we were expecting. No cure could possibly do more damage than this disease, and returning to “normal life” is now an impossibility. It will never happen, because Adam Schlesinger laughing and fathering, joking and composing was normal life. And that is all gone forever.

Several years after college, Adam and I sat in my apartment brainstorming about writing a musical together. About what? In what style? I put on Sondheim’s Company. I noticed that Adam looked like Sondheim had in the early ‘70s as he fretted through the documentary of the making of that musical’s Broadway soundtrack, though Adam was ten years younger. Adam picked up a half-size, out-of-tune guitar and preceded to play a ska, then samba, then emo, and finally baroque version of “Being Alive.” “Hurry up and pick one,” he said. “We open tomorrow.”

Adam’s first “professional” theater gig was writing the music and running the sound booth for a sketch comedy show I was writing with John Leguizamo at 1st Avenue’s legendary downtown performance space, PS 122. I got more enjoyment listening to Adam and Steve Gold arguing in the two-foot by four-foot sound booth about sound effects or music that came too early or too late — due to the actors’ improvising — than I did from the show itself. I remember turning to look back at Adam in the booth, pissed due to a late cue, then seeing him in there, harried and scrambling. I just felt lucky, knowing the most talented person in the building was noodling Madonna’s “Vogue” on a synth and hitting buttons that made Speedy Gonzales’s “Arriba, arriba … Andale, andale!” echo through the building.

This series of sketches was expanded into a network television show, House of Buggin’, that was the beginning of Adam’s career as a TV and film composer. I’d love to take some kind of discovery credit, but my sensation is not so much one of pride as privilege. If you’re alone on a hike and fortunate enough to catch a beautiful sunrise, you don’t feel like you caused it, you just feel blessed you were in the right place at the right time to experience it. I’m reminded of a conversation I had with Austin Pendleton years ago. I’d brought up that he was the first person to cast Philip Seymour Hoffman in a professional production. Austin grinned: “David, anyone with eyes who had been there would have cast him.” Adam’s talent was always unmistakable. Adam’s success was always inevitable.

***

A few years ago, as Adam and I discussed parenthood over drinks at the Knickerbocker, I said I’d seen that Company documentary again recently. “You still look like Sondheim,” I said. “But now he’s the one who’s younger.” Adam took a sip of his whiskey and said, “Check back in a few years and I’ll be a ringer for Elaine Stritch.”

Like so many of Adam’s fans, over the past few days I’ve turned to his music, looking there for comfort. Looking there for Adam. But even his most upbeat songs now sound discordant and dark. So much of Adam’s music was optimistic. Even his most melancholy songs always promised a crunchy, upbeat power chord just around the corner. But the virus that had hijacked my friend’s cells wasn’t content to stop there. The coronavirus had also infiltrated his music, burning through and re-writing his songs as it had his cellular DNA.

The virus has forced us into solitude and isolation. We’re bereft. But my friend’s alone, and I need to find him. In my mind I skip from song to song, trying to outrun the plague in search of Adam as lyrics to various songs conflate in my head.

And now you’re leaving New York.

For no better place.

You’re going nowhere.

And I’ll be there too.

When you lose someone you love, you just want the person back. And when you realize that’s impossible, the next impulse… You just want to join him.

I wanna sink to the bottom with you.

I just wanna, I just wanna, I just wanna….

I might as well go under with you.

In 1996, when I was first filing away Adam’s debut album, I went to the F’s, making space between Fugazi and Fleetwood Mac and Foreigner. I remembered extolling and critiquing each of these bands with Adam, who commented on people and music in the same way. He’d say something admiring and analytical, then sarcastic and funny. And then sincere.

I decided not to file Adam’s first album in the F’s. I keep it in my “need to listen to more” section, right beside the same worn copy of Reggatta de Blanc that Adam held up to me when he was 17.