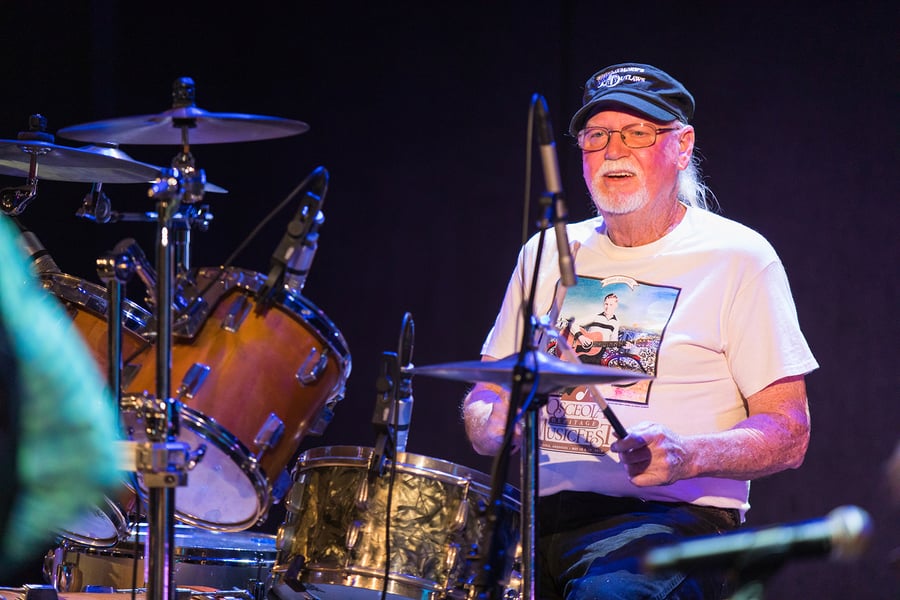

Richie Albright, who manned the drum kit for Waylon Jennings since the Sixties and was essential to the Outlaw country trailblazer’s signature rock-based sound, died suddenly Tuesday in Nashville. He was 81. A rep for Shooter Jennings, with whom Albright toured up until 2017, confirmed Albright’s death to Rolling Stone.

An Oklahoma native, Albright joined Jennings’ backing band the Waylors in 1964 in Arizona, and the group developed a fan base at the Tempe nightspot J.D.’s. Jennings’ first album, in fact, was named after the club, Waylon Jennings At J.D.’s (Albright is credited as “Richard Albright”). The two men developed a strong bond and Jennings relied on Albright as both a musical guide and confidant. It was Albright — whom Jennings once referred to as “my right hand” — who added a four-on-the-floor rock beat to Jennings’ country-rock guitar, adding another component to the oft-imitated Outlaw country sound in the process.

“His style of guitar playing was definitely different,” Albright told Michael Streissguth of those early J.D.’s gigs for the author’s 2013 book Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris and the Renegades of Nashville. “We did Dylan songs. We did Beatles songs. We did all genres of music. Did a lot of country stuff. It was kind of a castoff of Buddy Holly’s rhythm. It wasn’t country really.”

Jennings famously used the Waylors on his studio albums, a move considered against the grain in staid Nashville, with Albright keeping the beat on 1973’s Lonesome On’ry and Mean, 1976’s Are You Ready for the Country, and Jennings’ breakthrough, the 1973 collection of Billy Joe Shaver songs Honky Tonk Heroes.

In 1977, he played on one of the subgenre’s indelible hits and Jennings’ first crossover single, “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love),” off the Ol’ Waylon album, produced by Chips Moman.

“We cut the thing and everybody said, ‘Yeah, that’s a pretty good song,’” Albright told Rolling Stone in 2017. “I don’t think it really sunk in with anybody in the band until after it had been mixed. Everybody goes into the studio, turns down the lights, and puts on the record. When it finished playing, everybody went, ‘Damn.’”

But Albright also said that Jennings grew tired of the song: “He said, ‘Just remind me when I’m picking singles from now on that I got to sing that motherfucker every night.’”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Beginning with 1978’s I’ve Always Been Crazy, Albright began producing Jennings’ albums alongside the artist, including 1979’s What Goes Around Comes Around and 1980’s Music Man. He returned to the producer’s chair with 1990’s The Eagle.

In addition to playing with Jennings, Albright worked with luminaries like Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Jessi Colter, and Jennings’ son Shooter — whose middle name, Albright, was a nod to the drummer. As a member of Waymore’s Outlaws with the singer Tommy Townsend, Albright continued to play Jennings’ songs on the road, keeping alive the memory of the man he considered family.

In his 1996 autobiography Waylon, Jennings praised Albright as the catalyst for his enduring sound. “I’d turn around and look at Richie and we’d be going off on this tangent, jamming, letting the song carry us along, and a smile of satisfaction would spread across our faces,” he wrote. “I just knew musically we fit.”

Albright’s drum kit is currently enshrined in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, as part of the museum’s Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ʼ70s exhibit.

From Rolling Stone US