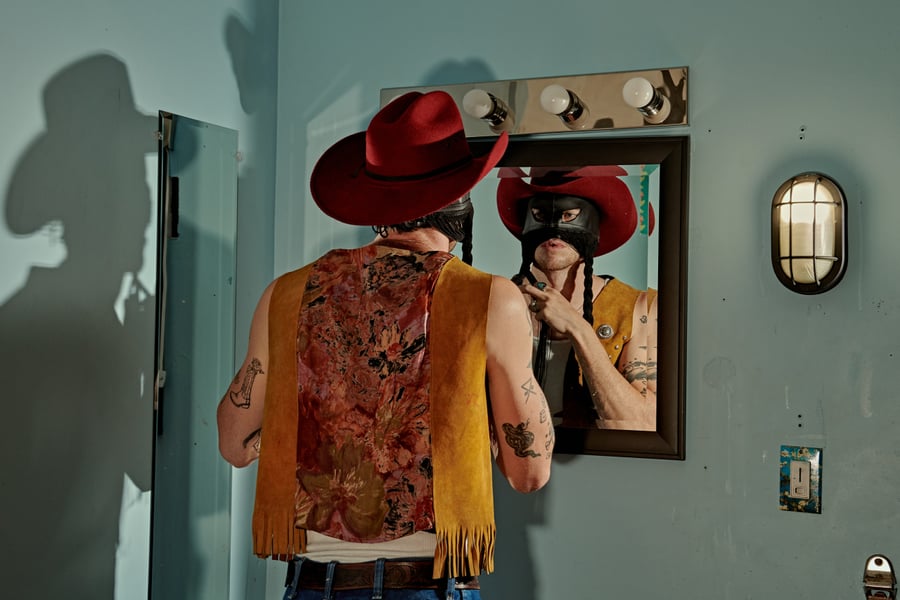

It may sound obvious, but Orville Peck doesn’t particularly go for casual dress. The masked entertainer tends to complement his signature facial fringe with bright colors and rhinestones, nods to a bygone era of country music when the entertainers lived large and wore the clothes to prove it.

“That’s what I grew up loving,” Peck tells Rolling Stone. “I’m not the kind of guy who wants to go onstage in jeans and T-shirt and pretend that’s me being real, because the real me is someone larger than life. I feel like sometimes people interpret what I do as a gimmick or a costume, but the reality is that’s just who I am.”

That’s not much of an overstatement — Peck seemingly sprung from nowhere in 2018, an enigma and an instantly recognizable star all at once. Legendary indie Sub Pop released his 2019 debut Pony, a gloomy, rumbling collection of tunes that sounded like Roy Orbison fronting Mazzy Star. Supported with near-constant touring, it became a bona fide hit and earned nominations for Canada’s Juno Awards and Polaris Prize. He made the jump to Columbia Records and released his Show Pony EP on on August 14th. In addition to queered narratives about truck drivers and lonely cowboys, Peck sings with Shania Twain and covers the Bobbie Gentry / Reba McEntire chestnut “Fancy” with a wild, Nick Cave-like intensity. His true identity is irrelevant at this point; he is Orville Peck, and Orville Peck is him.

During quarantine, Peck was forced to take his first break from the road in a long time, save for his second annual Rodeo at the Vogue Theatre in Vancouver, British Columbia, in late August. Otherwise, he’s mostly been at home in Los Angeles, writing new songs.

“I really miss performing, I really miss touring, touring is like my favorite thing,” he says. “For the meantime, I’m just writing a lot of music and trying to enjoy settled-down life for the first time in my life. I’ll keep you updated if I lose my mind.”

When you released Pony, it was such a fully formed thing, and nothing else really sounded like it at the time. How did you develop your sound?

Pony was so special because it was after a long hiatus from making music. I wanted to bring together elements of many different things that inspire me, so obviously, classic country and the showmanship and performance of a very specific era of country and western. I wanted to combine that homage and love of country with some newer references and elements, things that weren’t necessarily typical to the country sphere. It was just all the things I loved thrown into one because I also felt like that was really missing in country. I think people think I was trying to challenge it or that maybe I dislike country now, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. I’m such a huge fan of country and I have such a respect for it as a genre. I saw something missing from it that I wanted to see in it, so I decided to just do it.

Have you had a lot of people bait you into conversations about authenticity? Do you find yourself having to discuss that, or having to avoid those discussions?

Yes, constantly. It’s funny you say that because the irony of the whole thing is that some of my biggest fans are country fans, real authentic country music fans, and some of my biggest supporters are legendary country musicians themselves. People like Tanya Tucker or Shania Twain.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Shania went through a lot of those same things when she broke through in America: she wasn’t country enough, or she was somehow fake.

It’s the ironic thing about being criticized within the country world, or being questioned in the country world — it doesn’t really bother me because I feel like that has happened to so many legendary country performers who no one would ever consider questioning whether they were in the country canon. Something new comes into it and everyone gets their back up and wants to question the authenticity. Thankfully I will actually say that the reality is I feel like I’m very much accepted by the country community. Country fans don’t get enough credit for how much diversity and open-mindedness they actually want to see in their music.

You explore a lot of gay themes in your work. There have obviously been gay people involved in the creation of country music forever, but those stories aren’t as prominent. Still, it’s possible to see what Dolly Parton, Tammy Wynette, and Tanya Tucker were doing as flirting with camp, whether they realized it or not. Was that your experience?

Absolutely. A figure like Dolly Parton, it makes total sense to me that she’s a gay icon. That’s a unique person who understands what camp is, and camp is the intersection between performance and sincerity and Dolly Parton really epitomizes that. Dolly had a very interesting struggle within her own career, coming up first with Porter Wagoner and then going off on her own. She faced a lot of criticism in her life too — a lot of female country acts have not only faced a lot of criticism, but a lot of scrutiny, and not always been given the same opportunities as their male counterparts. So being gay and growing up listening to country music — I loved Merle Haggard and Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson and all of that, but I think I probably, whether I knew it or not, subconsciously connected more to people like Patsy Cline and Dolly Parton and Tammy Wynette and even Loretta Lynn. The female perspective in that space, the struggle of that, was probably closer to what as gay people, or queer people, we go through and experience.

With this year’s Show Pony EP, what adjustments did you feel like you needed to make, and do you see it as a bridge to whatever comes next?

I keep joking it’s like the middle sister, the troubled middle sibling. I don’t think my sound will ever change massively, to be honest, because I’m over 30 years old now and I still listen to the same records now that I’ve been listening to for 15 years. I don’t think I’m going to be making trap music on the next album or anything. But with Show Pony I had a different confidence. It’s funny, all my songs are tributes to eras of country or songs or tropes of country that I grew up loving. I put my own perspective on them and I have my own history into them. A perfect example would be a song like “Legends Never Die,” the duet I wrote for me and Shania. I don’t think I would have had the guts to do that on Pony, even though I probably wanted to, to make a Neil Young and Crazy Horse-meets-Nineties-radio-country rock banger.

“I was at the Grammys and during one of the commercial breaks, I heard someone calling my name. It was Shania”

It does sound the most like a country radio song I’ve ever heard you do.

Yeah! I kind of wanted it to be like a Tim and Faith song or something. That’s a part of country I love as well and on Pony I wouldn’t necessarily have had the courage to do that in a weird way. So with Show Pony, it’s not that I’m trying to change my sound — it’s an evolution of sorts, but it’s an evolution in my confidence. It hasn’t changed me as an artist, it’s maybe revealing more of me as an artist.

How did you get connected with Shania?

Someone told me she was a fan of mine fairly early on, last summer during the Pony era. I just didn’t believe it, to be honest. I thought the person was lying [laughs] or maybe misunderstanding. And I heard it again from someone else and I thought, “Oh my god, I guess this might be true.” I decided to shoot my shot and write a duet for us. I wanted it to feel really lazy and nostalgic but with a big punch, because there was a great era of Nineties country that felt rocking but also innately laid back. I thought it would be a cool thing for Shania. I wrote this song and sent it over to her people. I didn’t really hear much back, but then I figured it was a bit of a pipe dream and wrote it off. I was at the Grammys this year and during one of the commercial breaks, I heard someone calling my name. I turned around it was Shania coming down the aisle. She pulled me up out of my seat and gave me a big hug, and was like, “I’m such a fan of yours and I love the song you wrote for us and I can’t wait to work on it with you.” I lost my mind, obviously. I remember sitting back down, I don’t even know if I said anything back to her, which is crazy because I think I was genuinely speechless. Three months later, I was at her ranch in Las Vegas and we were hanging out with her horses and working on the song together.

At times Pony sounded really bleak, with “Dead of Night” and “Nothing Fades Like the Light.” Show Pony starts off almost in a weirdly optimistic place with “Summertime.” What did you have in time when you wrote that?

“Summertime” is funny. “Summertime” is about missing something that’s just out of reach or maybe it’s right there next to you but something about it has changed so you can’t love it the way you used to or maybe there’s something preventing you from enjoying it. It’s keeping the hope that that’s temporary and you can get back to this thing or this person or place that you love. It is a very positive song and it is hopeful, but I also think that hope can be a really devastating letdown sometimes. So it arguably might be the saddest song of all.

You sing about the solitude of cowboy life pretty regularly, and there are some parallels between that experience and that of queer folks living in rural areas. There is frequently distance between you and your lovers or other queer folks. It gets lonely.

The best thing about a country-western star to me, someone like Johnny Cash — the Man in Black, the voice of the imprisoned and the unwanted — those are sincere things about Johnny Cash, but he blew it up to a legendary performance status. Dolly Parton, the girl from Tennessee who grew up barefoot fishing on the river and she was bubbly but she could never catch a break. That’s the reality of who Dolly Parton is as a person, but she’s also blown that up to a performative, over-the-top level. I grew up feeling like an outsider my whole life. I have a very hard time talking about my emotions and feelings. I’ve traveled my whole life and never felt settled down, so to me the country-western, over-the-top version of who I am is like the Lone Ranger, a storybook cowboy who goes around town to town and lives from heartbreak to heartbreak, because that’s sadly kind of the reality.

Orville Peck at the Music Hall of Williamsburg for Rolling Stone (Photo by Victor Llorente)

From Rolling Stone US