There is no such thing as a casual Frank Zappa fan — it’s an all-or-nothing proposition. (Really, there’s no such thing as a casual Frank Zappa listener, period: You either immediately recoil from his grandiose, often goofy odes to dancin’ fools and yellow snow, self-promoting pimps and and S&M aficionados … or you end friendships arguing over which bootleg of his Over Nite Sensation ’73 shows is the best.) And on a scale from one to plays-in-a-Joe’s-Garage-cover-band, we’d put Alex Winter’s level of worship somewhere near an eight. To call Zappa, his exhaustive new documentary, a labor of love would be putting it lightly — it’s a six-years-in-the-making valentine to someone who’s obviously an idol to the actor-filmmaker. Having gained the family’s blessing and access to the prolific musician’s personal vault, Winter has unearthed an ungodly amount of rarely seen and heard stuff, from early home movies to interviews filmed a few months before Zappa’s death in 1993.

That alone would make this essential viewing for the type of folks who’d walk down their wedding aisle to the skronk-funk of “Peaches En Regalia.” But the documentarian has a secondary agenda in mind. So yes, you get the full rockumentary treatment: his childhood and Eisenhower-era teen years, when this son of a chemist was obsessed with blowing things up; his discovery of musical expression, courtesy of an “evil, vile” album by French composer Edgard Varèse; his introduction to R&B and gutbucket blues courtesy of Don Van Vilet, the future Captain Beefheart; and how being framed by the vice squad in Cucamonga, California, fueled his lifelong rebellious streak. The first iteration of the Mothers of Invention gets a good amount of screen time; the second “Flo & Eddie” group (when the Turtles’ Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan joined a new touring band), a little less so. We see how his going-independent gamble in the ’70s paid off handsomely, and how the Barking Pumpkin era begat “Valley Girl,” which gave Zappa the one thing he didn’t want: a hit record.

Winter also makes sure he pays lip service to Zappa’s collaborators, some peripheral and some key. A who’s who of musical virtuosos (Steve Vai, Terry Bozzio, Adrian Belew, Chester Thompson) whiz by in clips, though only Vai ascends to talking-head status. Several Mothers players, notably Ruth Underwood and Bunk Gardner, share anecdotes about “the ersatz Pied Piper of Laurel Canyon,” as does Alice Cooper and GTOs superstar Pamela Des Barres. Graphic artist Cal Schenkel and Zappa’s animator-in-residence Bruce Bickford get credit where credit is due in regards to the visual components. Most importantly, Winter gives a good deal of the spotlight to the late Gail Zappa, a doe-eyed hippie chick who met Frank in the mid-’60s and became his wife, his muse, the mother of his children, a major creative partner-in-crime and his long-suffering Rock of Gibraltar. Though Zappa was already a gigging musician by the time they met, it’s impossible to walk away from the doc without thinking that sans Gail, there simply would not have been a three-decade Zappa legacy.

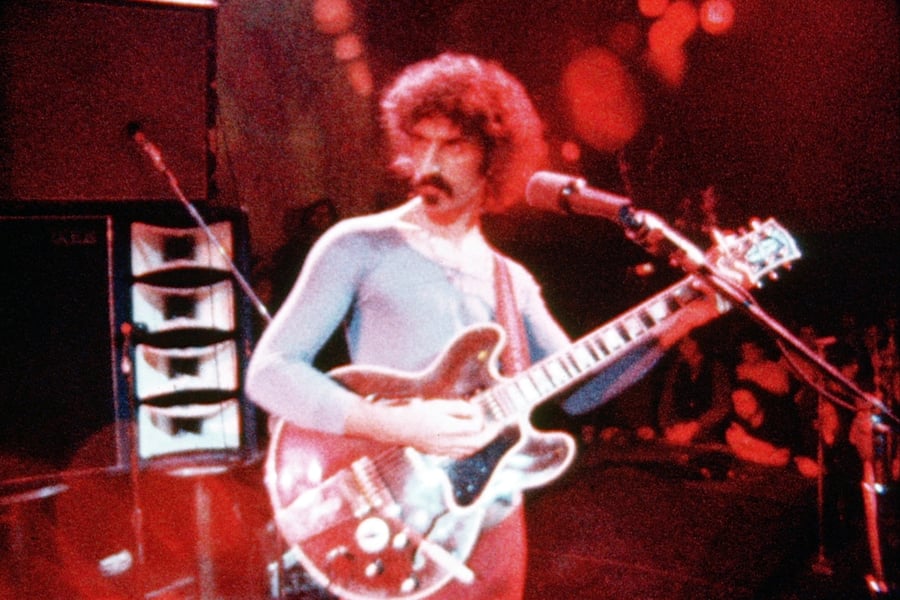

But she isn’t the focus of Winter’s mission of reclamation. Everyone thinks of Frank Zappa as the Pope of Prog Irreverence, the ultimate sardonic motherfucker with the Zapata mustache and that Bavarian Forest of a soul patch. He was the human embodiment of a smirk who seemingly played songs in the time signature of π, yet still gifted the world what one interviewee calls “crowd-pleasing, really filthy shit.” (We don’t know about crowd-pleasing, but can testify to the filthy part. Seriously, have you listened to Sheik Yerbouti‘s “Bobby Brown Goes Down” lately?!) Yet Winter mainly builds the bulk of his doc off a single statement: “I didn’t consider him as a rock star. He was a composer.” This is the thesis that Zappa pushes to the forefront. Frank’s orchestral work gets a lot of play here, much more than his rock stuff (the scarcity and brevity of his ’66-’78 live footage is likely to frustrate his guitar-hero fans). And if you don’t necessarily walk away thinking he’s a true peer of John Cage, Schoenberg, Bartók et al., you do gain a serious appreciation for his composing chops. Don’t think of the man as a shaggy-maned satirist/shock artist, it tells us. He was really a Modernist Mozart.

Zappa was both, of course, and Winter’s impressive doc admittedly works better as a preaching-to-the-choir portrait than a work of advocacy or conversion. But it is one hell of chronicle of Frank the Walking Contradiction: He was a rock star and a symphonic composer. Zappa was the poster boy for ’60s long-haired kooks and freaks who hated hippie culture, who made psychedelic music yet considered drugs a scourge upon society, and who insisted on breaking all the rules yet was a tyrant as a bandleader. He was a self-proclaimed self-centered person who stood up for other freedom of speech when the PMRC came a-callin’, despite the fact that they weren’t going after his music.

No one needed to stand up for this musical genius, yet Zappa does so nonetheless, and the fact that it goes the extra mile makes all the difference. “I’d rather not have [my music] played than to have someone play it wrong,” Zappa says at one point. The documentary makes you thankful he didn’t always stick that notion.

From Rolling Stone US