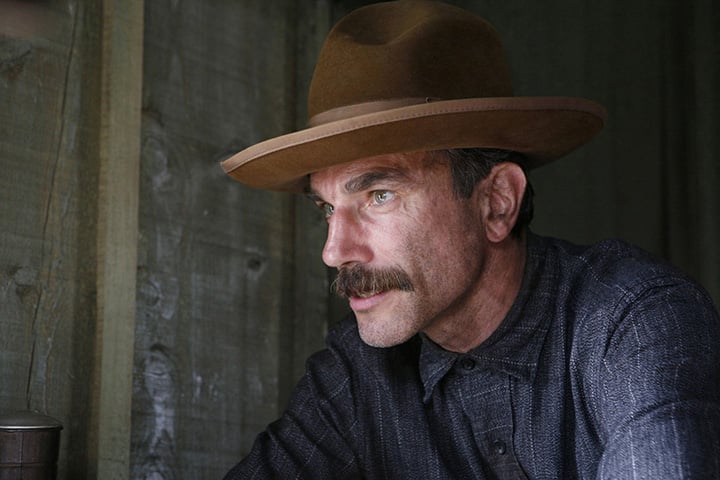

Daniel Day-Lewis has earned many accolades and awards over the last 35 years, but perhaps no one has more perfectly encapsulated this actor’s appeal than comedian Paul F. Tompkins. Cast in a tiny part in 2007’s There Will Be Blood opposite Day-Lewis, the stand-up comic later related what their first on-set encounter was like. “Now, I had been told that Daniel Day-Lewis was kind of an intense person,” Tompkins says. “And he’s really not. He’s really … THE MOST INTENSE PERSON that has ever lived on Earth. He’s not doing anything – he’s just sitting in a chair – and I am terrified of him, as if a jungle cat has wandered onto the set.”

It’s funny, yes – but there’s something incredibly accurate about Tompkins’ observation. If it’s true that Day-Lewis is indeed retiring after Phantom Thread, his latest collaboration with Paul Thomas Anderson, hits theaters in December, then we’ll miss the sleek, jungle-cat ferocity he brought to his best roles. Other tributes will praises this peerless performer’s obsessive preparation – learning Czech for The Unbearable Lightness of Being, living off the land for months for The Last of the Mohicans – and while that’s an indication of the commitment he brought to his characters, such testimonies make the performances themselves feel like burdened ordeals. Nothing could be further from the truth. Part of the pleasure in watching him on screen was being able to sit back and savour as he devoured a role with ravenous glee. Other actors pour themselves into their parts; few brought such lip-smacking gusto. He made the craft of acting look like so much damn fun.

Starting in 1985, with A Room With a View and My Beautiful Laundrette, Day-Lewis began wowing audiences and critics. In the former, he played a haughty twit; in the latter, he was a gay, soulful street tough. In his review of Laundrette, Roger Ebert noted that “seeing these two performances side by side is an affirmation of the miracle of acting: That one man could play these two opposites is astonishing.” Miracles never ceased with him onscreen. Day-Lewis soon won his first Best Actor Oscar – the first of three, the only man to date to make such a claim – for My Left Foot, in which he played Christy Brown, an artist born with cerebral palsy. It’s the sort of part that frequently leads to awards, but it’s a testament to his restlessness that what, for other actors, would be a career-defining performance became merely a jumping-off point. Along the way, he often looked like he was having a ball.

And it’s not that he couldn’t play men being torn apart by their passions – The Age of Innocence and In the Name of the Father bear that out. But Day-Lewis is almost second to none in his ability to make suffering feel revelatory and cathartic. Watch Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of the Edith Wharton novel about desire and class structures, and you’ll feel how his refined, muted Newland Archer is inextricably pulled toward the melancholy tractor beam that is Michelle Pfeiffer’s Ellen Olenska. But Day-Lewis renders the character’s romantic anguish with such crisp urgency that it goes beyond Masterpiece Theatre mannerisms. He’d Initially balked at the part – “I was hoping he’d ask me to do something more rough-and-tumble,” he later admitted – but the actor figured out how to bring raw energy to a restrained role. Rather than folding Archer’s misery in on itself, Day-Lewis projected it outward. You are ensnared by the same spell the Countess had weaved on him.

He was just as remarkable in other new guises. As Hawkeye in The Last of the Mohicans, he internalised his months of preparation to give us a bracingly authentic portrait of a rugged individualist, one dashing and thrilling all at once. With his broad chest exposed and sporting a flowing ponytail, the man looked like a three-dimensional replica of those hunky heartthrobs you see on the covers of period romance novels. Yet he figured out how to ennoble that cliché, imbuing this action hero with soulfulness and undeniable physicality, becoming the embodiment of director Michael Mann’s muscular, grandiose filmmaking.

Day-Lewis seemed to walk away from the profession in the late 1990s after The Crucible and The Boxer, well-meaning dramas that didn’t deserve the actor’s lethal focus. But he rebounded triumphantly. If the Eighties were Day-Lewis’ coming-out party and the Nineties his flirtation with Hollywood, then this century has seen him embrace larger-than-life characters that put his bravado on rich display. Gangs of New York started the run. His Bill the Butcher is a right bastard who rules 19th-century Gotham through violence, intimidation and a cocky grin that suggests he secretly (or not-so-secretly) wants to slit your throat. This reteaming with Scorsese started what you might call the jungle-cat period, the actor melding intensity with beautifully modulated showmanship. His turn as Bill was theatrical because Bill himself is – in another life and another era, this gangland murderer could have been in pictures.

After 2005’s The Ballad of Jack and Rose, a gentle father-daughter drama he made with his longtime partner Rebecca Miller, Day-Lewis delivered a trilogy of unbridled turns that occasionally made even Bill the Butcher seem timid. The greatest of the bunch is Daniel Plainview, the manically driven oilman of There Will Be Blood. Recently topping The New York Times‘ list of the century’s best films, writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson’s compulsively fascinating portrait of capitalism and religion at war for the soul of America strives for greatness at every turn – and Day-Lewis recognised that subtlety had no place in such a searing vision. It’s the monstrous, oversized performance that speaks directly to this epic’s themes, as if the actor (who won his second Oscar for the role) had absorbed all of the country’s grand contradictions to bring us this raging entrepreneur so full of ambition, so lacking of compassion for his fellow men. It wasn’t just Tompkins who was terrified and delighted by Day-Lewis’ volcanic stillness – he was merely the first of many viewers utterly absorbed in his mastery.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

A different kind of showman emerged in Day-Lewis’ gutsy turn as the conceited director Guido in Nine, an overblown, ill-conceived big-screen musical adaptation of the Broadway redo of 8 1/2. It’s far from the man’s finest hour, but Guido captures the actor at his most dreamy; you can forgive the guy for, on occasion, deeply digging the fact that he’s a glamorous movie star. That light palate cleanser, however, merely set the stage for his monumental turn in 2012’s Lincoln, taking on one of America’s most iconic and beloved figures. Nobody remembers now how daunting that task could be: Day-Lewis (winning his third Oscar) gave us a president beaten down by political and personal difficulties who, somehow, maintained his wonderfully dopey sense of humour in the thick of the Civil War. Who else other than the actor could have played Honest Abe with such offhand gravitas that you looked past the venerable president to see the very human, sparklingly intelligent man underneath the top hat?

Throughout his career, each time Day-Lewis essays a new role, audiences are greeted with a litany of tales regarding his infamous reluctance and mythic levels of preparation. (For instance, he first turned down Lincoln, writing director Steven Spielberg a lengthy letter articulating his reasons for why he didn’t feel up to the task.) These stories are passed around with a kind of hushed awe, as if these external factors are a key to his brilliance. As we await Phantom Thread, let’s take a moment to forget that sturm und drang and focus, instead, on the ripping elation his full-bodied performances have evoked.

Lord knows that’s what Day-Lewis would prefer. Speaking with Rolling Stone U.S. after Gangs of New York‘s release, he seemed frustrated by the legend that’s built up around his acting choices. “People talk, apparently on my behalf, about this torturous preparation period,” he said, “but it misses the point, because for me it’s sheer pleasure.” All this time, the agony we thought he’d been experiencing was actually ecstasy. It was his pleasure – and he made sure it was ours as well.