The Painter and the Thief, Benjamin Ree’s documentary on a curious friendship, starts with a crime. The Czech artist Barbora Kysilkova is exhibiting her work in an Oslo gallery — she’s recently moved to Norway to live with her husband — when two paintings are stolen. They are worth roughly 20,000 euros together; one of them, “Swan Song,” is considered to be her masterpiece. Surveillance footage captures a duo entering the building through a back door and exiting with two rolled-up canvases. The culprits are later identified and caught. During a hearing, Kysilkova approaches one of the accused. His name is Karl Bertil-Nordland. Why did you pick those two particular paintings to steal, she inquires. “Because they were beautiful,” he replies.

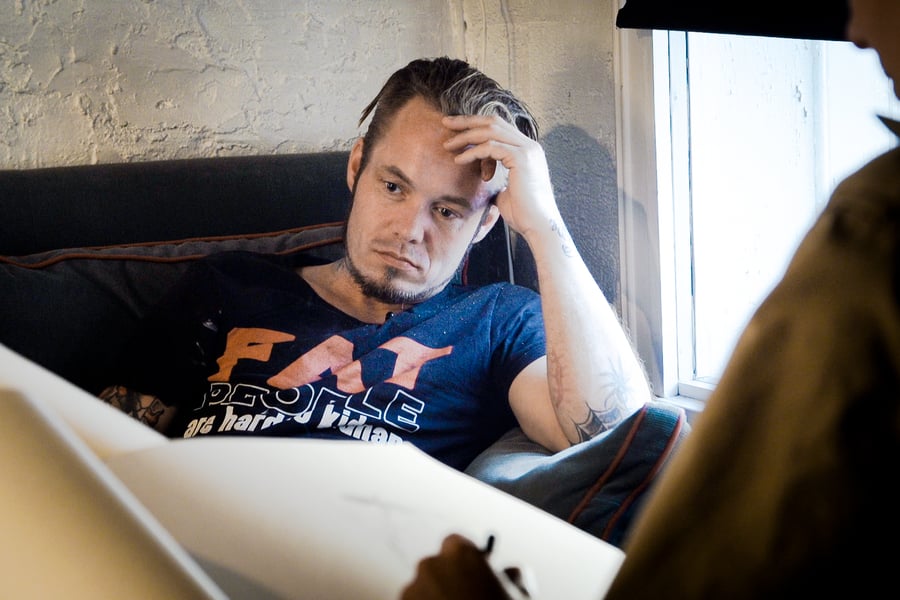

Ree has said that he had come across the case when he was researching the high rate of art theft in his the Scandinavian country, and had originally envisioned doing a short piece on the what, where and why of it all. Instead, he stumbled on to something a lot more intriguing. A drug addict and petty thief, Bertil-Nordland can’t remember what he and his partner did with their bounty. It’s all sort of blur, he says. As penance, the painter asks him to meet with her and allow himself to be sketched. The handsome, tattooed crook is confused by the offer. Still, he agrees to sit for Kysilkova. They chat, smoke, drink coffee; at times, it almost seems like the artist is flirting with her subject.

She also starts working on a proper portrait based on the drawings. They slowly get to know each other. Ree’s cameras capture all of this. Most importantly, he is there when Kysilkova shows Bertil-Nordland what she’s been up to, at which point you witness one of the most astonishing real-time emotional displays to be captured on film … and the documentary suddenly becomes an entirely different beast altogether.

A profound look at the art of healing — and the healing power of art — The Painter and the Thief ends up delving into the past of both people, and excavating lifetimes of pain, trauma, good and bad decisions. Bertil-Nordland, it turns out, was not always a career criminal; he loved to teach, he was a competitive BMX racer, he’s an expert in traditional carpentry. Kysilkova was not always a renowned artist, and has experienced more than her share of rough patches. Both of them are broken, with histories involving substance abuse, domestic violence, familial strife and ongoing self-destructive streaks. Stability is not a guarantee for either of them moving forward. But both contain multitudes, and if nothing else, Ree’s film is a tribute to taking the time to know someone, to hearing someone’s story, to forgiving transgressions, and to getting to the point where you can accept that you have something to offer.

That Ree was present to record their burgeoning, mutually life-changing bond feels like an insane stroke of luck. The fact that he’s shaped this footage into something so moving, however, is a testament to his talent and his subjects’ fearlessness. If the film flags a bit when the two of them have a temporary falling out and the focus shifts to Bertil-Nordland getting his act together and whether this friendship affected Kysilkova’s marriage (spoiler: yes, it did), these detours eventually prove to be gap-filling necessities. It makes the point at which we leave both of these people that much more affecting. You can be successfully creative or you can end taking a much more crooked path. As The Painter and the Thief so ably demonstrates, your life is worthy or compassion and consideration regardless.