Leonardo Wilhelm DiCaprio’s parents hung a painting above his crib in the grotty 1970s East Hollywood neighbourhood of Los Angeles when he was a baby. The painting wasn’t an action shot of Peter Rabbit or Curious George. No, it was a reproduction of Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch’s three-panelled “Garden of Earthly Delights”, a dystopian visual description of Eden being found and lost. It is one of DiCaprio’s earliest memories.

“You literally see Adam and Eve being given paradise,” says DiCaprio, his blue eyes peering above sunglasses in a Miami Beach restaurant that has somehow worked “SoHo” into its name. Underneath the table he fidgets his feet in and out of canvas loafers. He drifts away for a moment. DiCaprio just finished shooting an interview for a climate-change film he’s making. (Original working title: Are We Fucked?) He’s already been to India flood plains and the Antarctica polar cap, and now he’s not far from the Miami playgrounds where he once reputedly left a nightclub with every woman from his VIP section. All, according to DiCaprio, could be washed away.

He snaps back to the painting. “Then you see in the middle this overpopulation and excess, people enjoying the fruits of what this environment’s given us,” he says. He laughs a sad laugh punctuated by the DiCaprio smile that can be mistaken for a sneer. “Then the last panel is just charred, black skies with a burnt-down apocalypse.” He stops for a second before shrugging. “That was my favourite painting.”

Halfway between mother and maker, Leonardo DiCaprio is not unhappily marooned between the bright light of his own life – a looming Oscar, a personal fossil collection, a chauffeured rental Tesla – and the bleakness of the overheated world he inhabits with denialist Republicans and a Bangladesh coastline that could be nearly a quarter underwater by 2050. He wants us to move off fossil fuels entirely and wonders where we would be if we had spent billions on finding renewable energy sources rather than on the Iraq War.

“He has an intellectual restlessness,” says longtime collaborator Martin Scorsese. “He devours books and texts and information.”

A friend might tell DiCaprio to lighten up, but that’s not going to happen. “There are very few civilians who have the same understanding that this guy has of climate change. Leo’s a wonk,” says Mark Ruffalo, who has just combined forces with DiCaprio on the Solutions Project, a group of scientists and stars hoping to move America toward full renewable-energy use. “He’s putting his ass on the line.”

DiCaprio’s life-is-brutish-and-short worldview has permeated his post-Titanic film choices, especially his work with Scorsese, from Gangs of New York to The Wolf of Wall Street. He is now starring in The Revenant, the bleak tale of trapper Hugh Glass, whose body is demolished by a very angry grizzly, and who loses his family to the viciousness of the White Man. (Making matters worse, he must drag around Moses’ neck beard.)

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

“We went out there with the purpose of discovering something and seeing what nature was saying,” says DiCaprio of shooting The Revenant. The response? “This crazy, insane message that stopped production.”

Eventually, Glass is double-crossed by a man with half a scalp. He is left for dead, rides a horse off a cliff, sleeps in its carcass and chews on a bison liver. He remains mute for weeks. These are the lighter moments between arrows exploding arteries and knives removing testicles. During the Fitzcarraldo-esque shoot in the Canadian Rockies and Argentina, director Alejandro González Iñárritu burned through crew members. Iñárritu says that in their downtime he and DiCaprio would chew their own facial hair to pass the hours.

After that experience, maybe a Catch Me If You Can-style light comedy for DiCaprio? Not bloody likely.

“I would love to do something even darker,” says DiCaprio with a devious smile. He knows he sounds slightly mad. “I don’t know, like how would you penetrate the mind of somebody like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver? There’s a word in German that they don’t have in the English language that’s called schadenfreude. It means humiliation for somebody else.” He smirks. “It’s what I see sometimes when I watch certain politicians, but it can be done in movies, like when Travis Bickle takes [Cybill Shepherd] to the porno theatre for his first date. You’re like, ‘Oh, God, please don’t do this!'”

Not everything is so dark. There are still starlets, scuba diving and industrialist friends named Vlad with giant yachts. I ask him later if he’s afraid of slipping down into the gloaming like some character from a movie about a doomed 1912 cruise ship.

“I work hard at trying to create a balance.”

Successful?

“We’ll see.”

He makes his excuses and stands up. It’s time to jump into a helicopter and check out the suburban sprawl that threatens the Everglades. He takes a puff on a vaping device, exuding a maple-syrup smell that makes me want pancakes. He pulls a watch cap over his eyes and ducks out through the restaurant’s service alley. His chauffeured Tesla peels out for the heliport. A man left behind speaks into a wrist device, inadvertently proving that Leonardo DiCaprio is not just a man but also an organic commodity that can be used for good or evil.

“The package has left the building. I repeat: The package has left the building.”

Here’s the transitory question on the table: Is this the year Leonardo DiCaprio finally wins an Oscar, after four nominations? “Sure, everyone likes to be recognised, but that’s out of my hands – other people control those things,” DiCaprio tells me as he preps for an interview with a hurricane expert. “I will say it would help the film, bring it to more people.”

“He uses his body and a pair of eyes to convey so many emotions”, says Iñárritu.

The Revenant is like free guacamole to hungry film critics, with Birdman director Iñárritu at the helm and best-living cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki shooting scenery that out-Malicks Terrence Malick. But it could be a tough sell to punters plopping down $10 at the West Des Moines multiplex on date night. There are only two female characters in the film. One is murdered; the other is gang-raped by French trappers. The film is 156 minutes long, and it becomes quickly evident that any white character not named Hugh Glass is going to make the worst possible moral choice imaginable. But DiCaprio’s performance holds this cinematic hellscape together. (When Iñárritu saw him with his long beard, he exulted, “This man is a fucking trapper!”) DiCaprio is largely silent for the film, a feat harder than it sounds.

“He uses his body, which is wounded, and a pair of eyes to convey so many emotions in takes that are six or eight minutes long,” says Iñárritu. “He has to make us believe that he is cold, that he is wounded, that he is devastated, that he is angry, that he is hopeless. Without one word, you have to understand what this guy is thinking and feeling.” There’s a scene where DiCaprio finds his dead son and is broken. But he hears a crow singing beyond the trees. You can see him taking in death and life simultaneously.

“He was interacting and listening to every piece of nature and wind, and reacting to that,” remembers Iñárritu. “That’s the most difficult thing to do, and in the moment that he did that, I said, ‘This guy is really present. He has this rhythm, and he owns that rhythm.’ ”

For DiCaprio, the roots of The Revenant and his environmental work all began with a meeting with then-Vice President Al Gore in 1998. DiCaprio had grown up with a melancholy for extinct creatures – he once impressed Dr. Kirk Johnson, the director of the National Museum of Natural History, with his knowledge of the long-gone great auk, a bird hunted to extinction in the 1800s.

“I remember the thing that I got the most sad about when I was little was the loss of species that have been as a result of mankind’s intrusion on nature,” says DiCaprio, whose Los Angeles home features a massive fossil collection. He then mentions three species, only one of which I’d ever heard of: “Like the quagga or the Tasmanian tiger or the dodo bird.”

Titanic came out in 1997, and DiCaprio went from promising actor of his generation to one of the most famous faces on the planet. There was the requisite news of bawdy behaviour and a slew of model girlfriends, some of which still trickles out in the tabloids, as he remains single. You can ask him about it, but he will wave it off, saying, “I liked it when you went to see a movie and you didn’t know everything about the actor.”

Like Warren Beatty, Robert Redford and Paul Newman before him, DiCaprio longed to be seen as something more than just a panty-dropper. A friend set up a meeting with Gore. The vice president sketched out the planet and the atmosphere on a chalkboard and told the actor, “You want to be involved in environmental issues? This is the most important thing facing all of humanity and the future.”

At first, it was just appearances at Earth Day events and the occasional conference, and then there was the narration of his climate-change film The 11th Hour in 2007. But in the past decade, it has gone from passion to obsession. “I am consumed by this,” says DiCaprio. “There isn’t a couple of hours a day where I’m not thinking about it. It’s this slow burn. It’s not ‘aliens invading our planet next week and we have to get up and fight to defend our country’, but it’s this inevitable thing, and it’s so terrifying.”

A couple of years ago, DiCaprio met with a casual friend, the actor Fisher Stevens, once known as Michelle Pfeiffer’s ex and the ethnically dubious star of Short Circuit 2, but now an accomplished documentary producer. The two had become reacquainted while filming the disappearing reefs in the Galapagos, an event made memorable for DiCaprio’s scuba tank malfunctioning while shooting footage and DiCaprio desperately looking for someone to help him to the top. He (of course) found Ed Norton, who shared air with DiCaprio as they slowly ascended to avoid the bends.

Stevens and DiCaprio talked of shooting a climate-change film that would feature DiCaprio as a man on a global pursuit for the truth. The film would be equal parts gonzo, absurd and scare-the-shit-out-of-you testimonials from scientists and leaders. (There’s a Joaquin Phoenix quality to some of it, with DiCaprio, in full Revenant shagginess, interviewing a pristine Bill Clinton with the New York skyline behind him.)

In the past decade, climate change has gone from his passion to an obsession. “I am consumed by this,” says DiCaprio. “There isn’t a couple of hours every day that I’m not thinking about it.”

Just as preproduction was starting for the doc, funding came through for The Revenant. Rather than pass on either project, DiCaprio chose to see a symmetry between the two, with Hugh Glass representing a man on the front end of the West’s destruction of the land and the extermination of other cultures, and DiCaprio’s documentary set two centuries later as the world faces the bill for all the raping and pillaging. The links grew stronger as DiCaprio visited the hellish Alberta, Canada, tar-sand oil fields, several hours north of the breathless mountains and streams of the Revenant set. Meanwhile, filming was repeatedly hampered by a lack of snow as Alberta “enjoyed” the warmest winter on record. The connections left Iñárritu and DiCaprio shaking their heads as they suffered through multiple delays.

“It was a parallel universe,” remembers Iñárritu. “We discussed it at length. It was scary to be depicting how it all started in this country, and now we’re suffering 200 years of consequences for that. It was a mirror. It was funny and scary as hell.”

“We went out there with the purpose of discovering something and seeing what nature was saying,” says DiCaprio about the shoot. He flexes his hands open and shut in frustration. “That was never directly articulated, but it was like, ‘OK, what happens if we put ourselves in the elements? What are we gonna discover?’ The thing that I was left with was this crazy, insane message of nature fighting back and essentially stopping production.” Later, he put it more bluntly. “The big question is, is it all too late?”

As the documentary crew travels from global bleak spot to bleak spot, Stevens has occasionally had to remind DiCaprio not to wallow too much in hopelessness. “I’m more the light and he’s the dark,” says Stevens with a grin. “I’m always saying, ‘Don’t be so fucking pessimistic, man. If we make a movie where it’s already too late, what are we making the movie for?’ ” Stevens smiles hopefully. “Leo gets that.”

We’ll see. DiCaprio has final cut.

It’s the Sunday after Thanksgiving, and Miami Beach is in a sleepy interlude between turkey and the hordes arriving later in the week for Art Basel, which is Sundance for the art crowd. Stevens and his crew are setting up in the city hall offices of Mayor Philip Levine to ask him about how rising waters are threatening the city (a line of questioning partially inspired by a 2013 Rolling Stone article by Jeff Goodell). DiCaprio arrives looking tired in a short-sleeved polka-dot blue shirt and droopy jeans exposing powder-blue boxers. He stretches theatrically.

“I think I got too much sleep last night.”

Stevens laughs. “That would be a first.”

DiCaprio is two-tracking obligations as details of The Revenant have started seeping out and his camp has had to tamp down rumours that he was sexually assaulted by a grizzly in one of the film’s gory passages (“That’s not what’s happening”). Then a veteran movie blogger said that he loved the film but there was no way women were going to sit through the gorefest. “I think it’s silly, and I think that the women I’ve spoken to really enjoyed the movie,” says DiCaprio.

But after a quick hairbrush session, DiCaprio shifts into environmental-warrior mode. Stevens gives him a list of questions, but he largely wings it. First, DiCaprio and Levine talk of mutual friends, including billionaire Russian construction magnate Vladislav Doronin.

“Our good mutual friend Vlad says hello,” says Levine, before telling a story about Doronin offering to take him out for an ocean swim and Levine joking about his fear of not returning.

“Vlad is a lot of fun,” admits DiCaprio, adding how much he enjoys Doronin’s Aman Resorts, discrete seven-star accommodations scattered across the globe.

Then they begin to talk. DiCaprio asks Levine if he’s worried about declining real-estate prices.

“I’m not going to preside over Miami Beach becoming Venice,” says Levine. “I think property levels are just going to continue to rise.”

DiCaprio doesn’t agree, saying he’d already unloaded his beach house: “I wouldn’t take that bet.”

Levine wants to show DiCaprio some of the work the glitzy resort town is doing to lessen the impact of rising tides, so we pile into the Tesla while the mayor travels in a black SUV. DiCaprio understands no mayor is going to come out in public and say, “Sell your condo, we’re screwed”, but he doesn’t share his optimism. “You know what they’re doing now?” DiCaprio asks. “They’re building high-rises where the lobby can flood and the rest of the building can just continue on. But he’s right, prices are still going up. It’s unbelievable.”

We stop at a section of streets that the city has raised one-and-a-half metres to provide a bulwark against the sea. The two do a walk-and-talk while Sunday brunchers begin to gawk and stalk at a careful distance.

We eventually reach the water, and it’s horrifying in an affluent kind of way. The water level has risen to nearly equal with boat docks, rendering ladders leading into the ocean irrelevant. DiCaprio and Levine walk out on a tenuous sea wall and look across the bay to where, coincidentally, their friend Vlad’s yacht glitters in the morning light. The mayor admits that the city needs $400 million to build new sea walls and a system of pumps and to raise roads. And that number doesn’t even include sand from the Bahamas.

DiCaprio nearly does a spit take.

“The Bahamas?”

The mayor nods and says Bahamas sand can be cheaper than American sand.

During a stop in the interview, DiCaprio points at a tan older gentleman combing his luxurious silver hair on a balcony in a nearby high-rise.

“Look at that guy,” says DiCaprio. “He has no idea what is going on.” DiCaprio watches him with fascination for a moment and then makes a joke. “He probably knows that he’ll be dead soon and won’t have to worry about it.” He glumly says goodbye to the mayor, and tosses his swag of Miami Beach caps and cuff links into his trunk.

He settles into the back of the Tesla.

“The Bahamas, did you hear that?”

The conversation turns to places like Bangladesh that don’t have the money to deal with the rising waters. “The story of climate change is gonna be places with the most military power to protect their own resources,” says DiCaprio, hitting the vape pipe. “The billions of people that haven’t contributed to this problem are gonna be the first to suffer.”

Above, the sun tries to break through morning clouds and shine light through the Tesla’s opaque roof. It is not successful.

At the People’s Climate March in New York, 2014

The image of Dicaprio as an empty libertine gorging in his own garden of earthly delights – which has stuck since he rolled with a travelling pack of ruffians derisively labelled the Pussy Posse back in the 1990s – isn’t any more true or false than it was with leading-man predecessors like Redford and George Clooney. (DiCaprio recently ended his relationship with model Kelly Rohrbach, according to reports; before that, the best rumour was of a casual liaison with Rihanna.) Has there been skeezy womanising? Perhaps, but DiCaprio was and is single, and you can see skeezy womanising at Buffalo Wild Wings on a Thursday night. There has been some twisted comeuppance; in 2005, DiCaprio had to get more than a dozen stitches to his billion-dollar face after a Hollywood Hills party when a former model slashed him with broken glass, a shot that may have been intended for someone else.

Beneath that reputation has been an actor devoted to his craft since his early tweens. DiCaprio was partially raised by an underground artist, his father, George DiCaprio, a comic-book author and distributor. Leo grew up in Los Angeles, but not the Los Angeles of Hollywoodland. As a kid, he saw junkies in the alleyways and prostitutes at the nearby hotel. After a halcyon stay at a progressive school near UCLA, he returned to his neighbourhood school for junior high, where he was regularly beaten up.

“I was a bit of a loudmouth, and I was in an environment where the elements aligned to have kids smack the hell outta me once in a while,” DiCaprio tells me with a smile.

DiCaprio found refuge in drama classes and started hitting auditions, driven by his mother, Irmelin, his most patient supporter and critic. (She’s been known to critique the wardrobe authenticity in his films.) There were cattle calls, a Matchbox commercial and a year when he wasn’t cast in anything. Instead, he took to his room and spent a year watching movies with his father’s guidance, developing a taste for films like East of Eden and A Face in the Crowd.

He knew acting was what he wanted to do and started making friends at auditions with other dreamers, like Tobey Maguire. “I’ve got plenty of new friends through the years, too, but I’ve held on to some of them for 25 years now,” says DiCaprio. “There’s an inherent comfort level that can’t be duplicated and can’t be manufactured. You don’t have to do catch-up interviews – they’re up-to-date.”

There was a part on the 1990s ABC sitcom Growing Pains, in the classic ratings-booster role of boy without a home. But it all changed when he beat out Maguire and others for the lead in an adaptation of Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life, starring opposite Robert De Niro. DiCaprio’s father had taken his boy to a screening of De Niro’s Midnight Run a few years earlier and told him if he wanted to be an actor, De Niro was the one to watch. DiCaprio thought he blew the audition by screaming his lines, but De Niro liked his intensity.

De Niro recommended DiCaprio to Scorsese, and when the actor and director worked together for the first time, on 2002’s Gangs of New York, it was a 26-year-old DiCaprio who was dispatched to Daniel Day-Lewis’ New York brownstone to try to lure him out of retirement, sitting with him on a Central Park bench and silently waiting for him to make the first move.

DiCaprio is cagey about his next film, but he’s been casting about for a project that speaks to his politics. He dreams of releasing his documentary in tandem with The Revenant‘s DVD release, and he has already optioned an unwritten book on the Volkswagen emissions scandal. There’s a great narrative film to be made about the environment, insists DiCaprio – it’s just a matter of finding the right project.

“I don’t know how to crack this yet, but I would love to do something that isn’t about waves crashing on the Empire State Building,” he says.

We’re eating at a posh Miami restaurant, and a stray little girl wanders by, with no clue that she is eyeing one of the world’s most famous movie stars. DiCaprio takes off his sunglasses and offers a long aww. I ask him if he sees time in his life for a family. He responds abruptly, the only time in our two days together.

“Do you mean do I want to bring children into a world like this?” says DiCaprio. “If it happens, it happens. I’d prefer not to get into specifics about it, just because then it becomes something that is misquoted. But, yeah.” He shifts uncomfortably in his chair. “I don’t know. To articulate how I feel about it is just gonna be misunderstood.”

One thing is clear: He’s not going to retire and chain himself to the gate of a BP plant. There has to be a strategy.

“I had a friend say, ‘Well, if you’re really this passionate about environmentalism, quit acting’,” he says. “But you soon realise that one hand shakes the other, and being an artist gives you a platform.” He pauses and offers his palms upward. “Not that necessarily people will take anything that I say seriously, but it gives you a voice.”

One afternoon, DiCaprio is heading in the Tesla to another appointment, and he wants to make something very clear.

“This is not my life,” says DiCaprio, dressed in the same outfit as the day before to maintain continuity in the shooting. He stares intently at me. “I’m not followed around by publicists, security guards, drivers and all that. That’s not my day-to-day life – it’s my professional life.”

Talk moves to what he loves to do most: scuba dive in exotic locations. He’s hit Australia, the Galapagos and multiple spots in the Caribbean. Even relying on the oxygen kindness of Edward Norton to survive hasn’t dampened his love.

“It’s a hypnotic, unbelievably beautiful ecosystem that’s below the surface of the world we live in,” says DiCaprio, his face relaxing noticeably. “It’s a complete escape from absolutely everything.”

Today is an escape of a different sort. DiCaprio is standing on a catwalk outside a giant glass tank simulating a hurricane at the University of Miami. As the waters pound a model house on a model beach, he makes a joke: “I spent a lot of time in a tank like this for Titanic.” For 45 minutes, a scientist tells DiCaprio about the shredding Florida will take during the next hurricane. DiCaprio hits the vape pipe during a pause and exchanges a look with Stevens that suggests, “You try to put a happy ending on this.”

DiCaprio says goodbye to the crew and says he’ll see them in Paris for the climate-change conference. He knows that one of the first things conservatives will throw at him is the amount of fuel used by the thousands of attendees.

“There’s no way we’re not all hypocrites,” says DiCaprio. “We’ve built this. Our entire society is oil-based. Everything that you see is because of fossil fuels. The day there is a sustainable way to travel, I’ll be first in line.”

For DiCaprio, the trip was worth it. After the Paris Agreement was signed, he declared, “[This] gives us a shot at saving the planet. There is no time to waste. This marks the end of the fossil-fuel era.”

But that’s a week away. For now, he has a few hours of downtime with his art-gallery friends. On the way downtown, I mention that his intensity on global warming is, well, intense.

“You noticed that, huh?” he says. “This has got to be the largest human movement in history, and it takes every religion, every country, every individual contributing to it.”

We arrive at a ritzy gallery that shows no sign of the coming apocalypse. Security guards swarm the car. I begin to say goodbye, but DiCaprio puts his hand on my arm. “Don’t worry, I’m not jumping out of the car.” He continues on for a couple more minutes about a new ally in the fight. “We finally have a pope for the first time that is speaking through his encyclical and has aligned himself with modern science.”

Someone knocks on the window. It’s time to go. DiCaprio opens the door, and the likely next winner of the Oscar for Best Actor is immediately engulfed in handlers. He turns back and shouts over his shoulder with a smile, “Nice talking to you, bro!”

For just a moment, Leonardo DiCaprio looks like a kid without a care in the world.

—

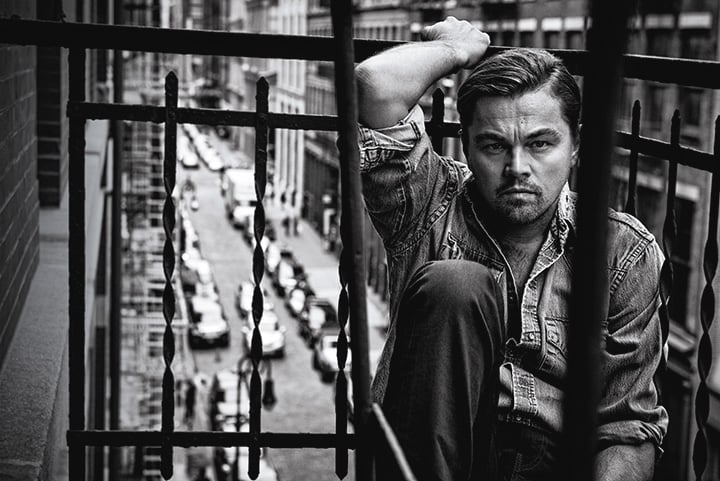

From issue #772, available now. Top photograph: DiCaprio in New York, 2015. Credit: Mark Seliger.