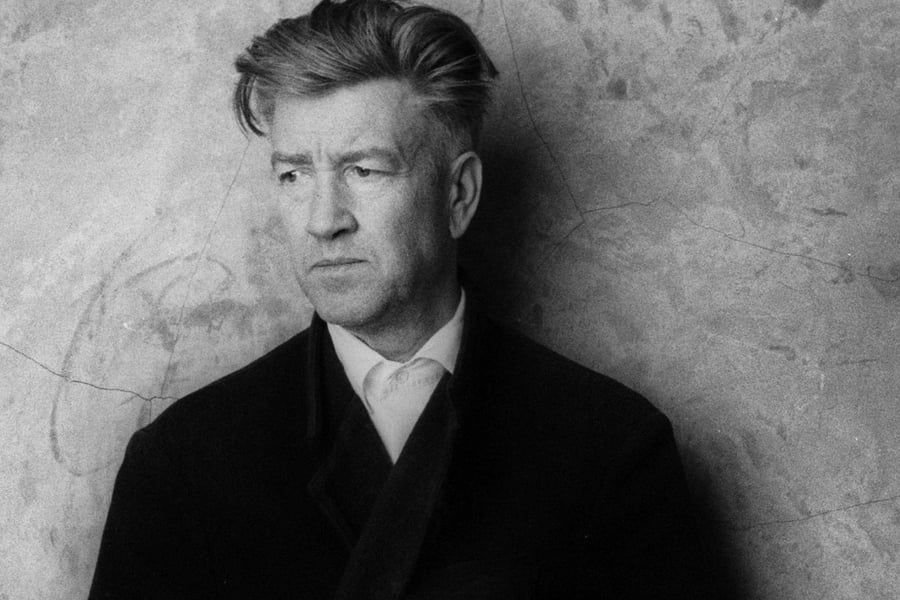

David Lynch, the singular American filmmaker and multi-disciplinary artist who conjured dreams and nightmares of unsettling beauty and psychic horror, has died. He was 78.

Lynch’s family confirmed his death on Facebook, writing, “It is with deep regret that we, his family, announce the passing of the man and the artist, David Lynch. We would appreciate some privacy at this time. There’s a big hole in the world now that he’s no longer with us. But, as he would say, ‘Keep your eye on the donut and not on the hole. It’s a beautiful day with golden sunshine and blue skies all the way.’”

A cause of death was not given, but in the years leading up to his death, Lynch was battling emphysema, which he contracted after years of smoking cigarettes (he revealed the diagnosis publicly in 2024). The disease left Lynch largely homebound, because the risk of catching Covid-19 or other bugs would potentially exacerbate his health issues. However, he continued to work, writing on Twitter at the time, “I am filled with happiness, and I will never retire.”

As a filmmaker, Lynch honed and presented a distinct style that teetered on the edge of the real and surreal. In masterpieces like Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive, and Twin Peaks (both the two TV series and the 1992 film Fire Walk With Me) he toyed with the mundane and the uncanny, balanced brutal violence and total love, and plumbed the depths of the supernatural and psychological. His work delighted, mystified, and horrified viewers, and rarely offered easy answers.

“They mean different things to different people,” Lynch said of his films in a 1990 interview with Rolling Stone. “Some mean more or less the same things to a large number of people. It’s OK. Just as long as there’s not one message, spoon-fed. That’s what films by committee end up being, and it’s a real bummer to me.” He added: “Life is very, very complicated, and so films should be allowed to be, too.”

Along with his 10 feature films and television work, Lynch directed an array of commercials and music videos, including visuals for artists like Nine Inch Nails, Moby, and Interpol. He was a dedicated musician himself, releasing a variety of solo and collaborative albums, including several with longtime composing partner Angelo Badalementi. And Lynch was an avid painter and visual artist, who exhibited his work around the world and spent nearly a decade drawing his own comic strip, The Angriest Dog in the World.

David Keith Lynch was born Jan. 20, 1946 in Missoula, Montana, but he spent much of his early life moving around the country due to his father’s job as a research scientist for the Department of Agriculture. His parents encouraged his artistic interests too: He drew on the reams of graph paper his father brought home from work, and said his mother “saved” him by refusing to give him coloring books where “the whole idea is to stay between the lines.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

But while Lynch’s childhood was, by all accounts, a calm and happy one — despite all the moving — he seemed cognizant of, and fascinated by, darker forces. In a telling exchange from that 1990 RS interview, he recalled the beaming smiles plastered on the faces of people in advertisements during the Fifties: “It’s the smile of the way the world should be or could be. They really made me dream like crazy. And I like that whole side of it a lot. But I longed for some sort of — not a catastrophe but something out of the ordinary to happen.”

He added: “Once you’re exposed to fearful things, and you see that really and truly many, many, many things are wrong — and so many people are participating in strange and horrible things — you begin to worry that the peaceful, happy life could vanish or be threatened.”

After high school, Lynch studied art in Washington D.C. and Boston, but got little out of the programs. He spent several years traveling around Europe, and when he returned, moved to Philadelphia and enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Around the same time, Lynch married his first wife, Peggy, and the couple had a daughter, Jennifer, in 1968. (Lynch and Peggy later divorced; Lynch would marry three more times and have three more children.)

Lynch has described his time in Philadelphia as both terrifying and deeply inspirational. One house he lived in was catty-corner to the city morgue, and Lynch once convinced the night guard to let him wander around. Another house was robbed on multiple occasions, with a boy who was murdered down the block in another home. “The feeling was so close to extreme danger, and the fear was so intense,” he said in the 2005 book Lynch on Lynch. “There was violence and hate and filth. But the biggest influence in my whole life was that city.”

It was during this time that Lynch experienced an epiphany: While staring at one of his paintings one night, he saw the colors start to move and heard the sound of the wind — an audio-visual sensation that convinced him to try filmmaking. He created his first short film, Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times), on a budget of $200 and released it 1967: Per its title, the animated short shows the bodies of six men filling up with a brightly colored bile, which they eventually spew out. It was, as Lynch put it, “57 seconds of growth and fire, and three seconds of vomit.”

Lynch’s early work found him experimenting with and mixing live action and animation, while exhibiting a sharp talent for horror and the grotesque. His 1968 short The Alphabet — in which a woman (played by Peggy) recites the alphabet then dies a gruesome death — helped him earn a grant from the American Film Institute, which he used to make his 1970 project The Grandmother. Around the same time, Lynch and his family relocated to Los Angeles, where Lynch studied at the AFI Conservatory and eventually began to work on what would be his debut feature, Eraserhead.

Filming began in May 1972 and took several years to complete, largely because of funding issues (the money came from a variety of sources, including grants, loans from Lynch’s father and friends, including Sissy Spacek, and even Lynch’s own paper route). The film tells the story of a new father struggling to survive in a bleak, industrial cityscape while his newborn, deformed baby screams constantly. Depsite the long production time, Lynch immersed himself in the film fully, in large part because he was actually living on set.

Eraserhead was finally released in 1977, earning mixed reviews and eventually becoming an underground midnight movie hit. One fan was producer Stuart Cornfeld, who worked with Mel Brooks, and eventually tapped Lynch to direct The Elephant Man, a drama based on the life of Joseph Herrick, an English artist with severe physical deformities. Starring John Hurt, Anthony Hopkins, and Anne Bancroft, the movie was a major hit and earned eight Oscar nominations, including Best Director for Lynch. (The film, however, went home empty-handed).

The Elephant Man immediately made Lynch one of the most exciting new directors in Hollywood. George Lucas even offered him the chance to direct Return of the Jedi, which Lynch declined. As he said in Lynch on Lynch, Star Wars was “totally George’s thing,” and he’d “never even really liked science fiction,” unless it was “combined with other genres.” Lynch tried to do just that on his next film, a big budget adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune, but the film was a critical and commercial flop. Lynch rued giving up Final Cut of the film, and even had his name replaced with a pseudonym on one version of the film that aired on broadcast TV.

In contrast, Lynch’s next project, Blue Velvet, was fully his. The neo-noir starred Kyle MacLachlan (who made his film debut in Dune) as a young man in a small town who hurtles into a harrowing underworld of violent abuse and unstoppable evil after discovering a severed ear in a field. Along with MacLachlan, Blue Velvet starred Isabella Rossellini, Laura Dern, and Dennis Hopper as the hellacious villain Frank Booth; it also marked Lynch’s first collaboration with composer Angelo Badalamenti.

Upon its release, Blue Velvet was a modest box office hit and divided amongst critics, though it did earn Lynch his second Oscar nomination for Best Director. The film’s legacy, import, and influence, however, is undeniable, thanks to Lynch’s inimitable mixing of white picket fence optimism, pop purity, and unadulterated evil.

“This is the way America is to me,” Lynch said of the movie in Lynch on Lynch. “There’s a very innocent, naive quality to life, and there’s a horror and a sickness as well. It’s everything. Blue Velvet is a very American movie.”

Lynch’s next movie, Wild at Heart, arrived in 1990. It starred Dern and Nicolas Cage as a couple on the run, featured a plethora of allusions to Lynch’s beloved Wizard of Oz, and won the coveted Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. But it was Lynch’s other 1990 project that left an even more indelible mark: Twin Peaks.

Prestige TV before there was prestige TV, Twin Peaks opened with the murder of homecoming queen Laura Palmer and followed the subsequent investigation, which only uncovered more secrets, both seedy and supernatural. The whodunnit made Twin Peaks an immediate sensation, but also arguably led to its demise. Under pressure from network ABC, Laura Palmer’s killer was revealed halfway through Season Two, leaving viewers with a big answer amidst an increasingly convoluted plot.

Lynch expressed serious regret over this choice, with his co-creator Mark Frost telling Variety in 2024, “David always said, ‘We should never solve the mystery — this should go on forever.’ And there’s a part of me that thinks he may have well have been right.”

Despite that early reveal, Season Two of Twin Peaks still managed to end on a cliffhanger, and Lynch retained his fascination with the Pacific Northwest town. His 1992 film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me dug into the last days of Laura Palmer’s life, and though it bombed upon release, it’s since been reclaimed as one of Lynch’s best works. Then, in 2017, Lynch spearheaded Twin Peaks: The Return, a new television series set 25 years after the events of the original show.

“It’s sort of like going back to a place where you grew up,” Lynch told Rolling Stone at the time. “You know your way around even though things are a little different. Memories come back and ideas come like that.”

The original success of Twin Peaks led Lynch to try a couple of other television shows with Frost, but neither On the Air or Hotel Room lasted more than a few episodes. He returned to film in 1997 with Lost Highway, another striking neo-noir that confounded audiences and critics but eventually found its devotees. And then two years later he released one of the biggest ostensible outliers of his career, The Straight Story, a charming, G-rated tale about a real-life World War II vet who drives his tractor across the country to make-up with his estranged brother before his death.

Of course, as only Lynch could, he followed The Straight Story with 2001’s Mulholland Drive: A haunting, multifaceted murder mystery and psychological drama, set against the always alluring, always repugnant, backdrop of Hollywood. (It also features one of the most terrifying jump scares in movie history.) The film is filled with clues to consider, ideas to chew on, and winding paths to follow, but Lynch rejected the notion that he was actively trying to tease or confuse his viewers.

“You never do that to an audience,” he said in Lynch on Lynch. “An idea comes, and you make it the way the idea says it wants to be, and you just stay true to that. Clues are beautiful because I believe we’re all detectives. We mull things over, and we figure things out. We’re always working this way. People’s minds hold things and form conclusions with indications. It’s like music. Music starts, a theme comes in, it goes away, and when it comes back, it’s so much greater because of what’s gone before.”

Lynch would direct just one more feature after Mulholland Drive, 2006’s Inland Empire, after which his last major project would be Twin Peaks: The Return. Still, he stayed busy, releasing a plethora of short films and web series (like his treasured “Weather Reports” — short clips uploaded to YouTube in which he’d discuss the weather in Los Angeles and share little aphorisms and musings). He even made a memorable cameo in Steven Spielberg’s semi-autobiographical film, The Fablemans, appearing as another legendary filmmaker, John Ford.

He turned more to music, releasing three solo albums — 2001’s BlueBOB, 2011’s Crazy Clown Time, and 2013’s The Big Dream — and a plethora of collaborative projects with Badalamenti, Jocelyn Montgomery, Marek Zebrowski, and Chrystabell. His last album, Cellophane Memories, with Chrystabell, arrived in 2024.

Last August, speaking with Sight & Sound for one of his final interviews, Lynch seemed as busy as ever. He said he’d pitched an animated project to Netflix that was turned down, and maintained the belief that he’d eventually get to make a film based on his 2010 screenplay, Antelope Don’t Run No More, even with his emphysema diagnosis hindering his ability to be out in the world. “Well, we don’t know what the future will bring, but we remain hopeful,” he said at the time.

In his 1990 Rolling Stone interview, Lynch captured the allure of his work, and the driving motivation behind it, when asked about a line that Cage’s character, Sailor, delivers in Wild at Heart: “We all got a secret side, baby.”

“I don’t want to see something so clearly that the would destroy an imaginary picture,” he said. “And I’m real thankful for secrets and mysteries, because they provide a pull to learn the secret and learn the mystery, and they provide a beautiful little corridor where you can float out and many, many wonderful things can happen. I hope in a way I don’t ever get the total answer, unless it accompanies a tremendous rush of bliss. I love the process of going into a mystery.”

From Rolling Stone US