The 99 Best Movies of 1999, Ranked

From ‘Phantom Menace’ to ‘The Matrix,’ ‘Fight Club’ to ‘The Virgin Suicides’ — we rank the standouts of a truly outstanding year at the movies

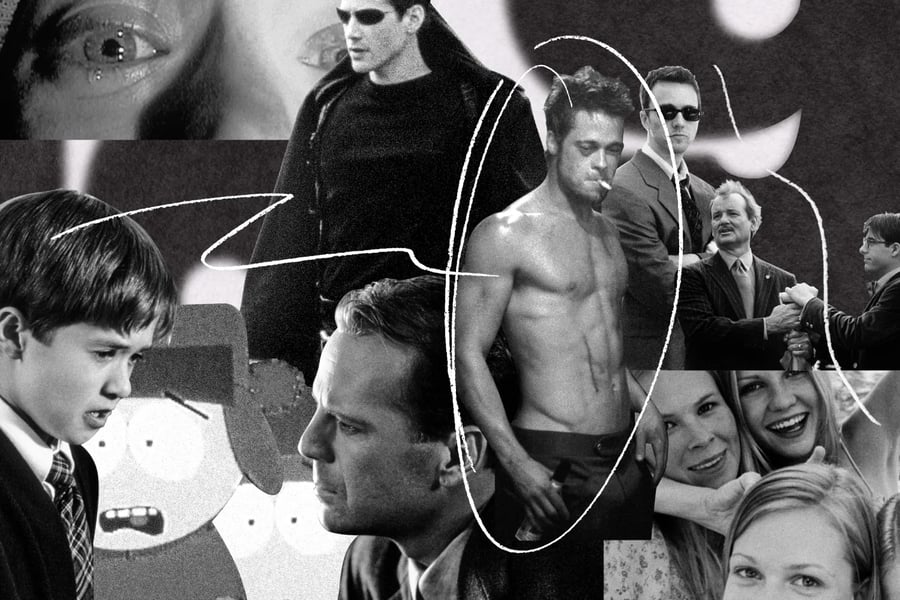

Clockwise from left: 'The Sixth Sense,' 'The Blair Witch Project,' 'The Matrix,' 'Fight Club,' 'Rushmore,' 'The Virgin Suicides.' PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY MATTHEW COOLEY. IMAGES IN ILLUSTATION: ©ARTISAN ENTERTAINMENT/EVERETT COLLECTION; BUENA VISTA PICTURES/EVERETT COLLECTION; COMEDY CENTRAL/EVERETT COLLECTION; 20TH CENT FOX/EVERETT COLLECTION; WARNER BROS/EVERETT COLLECTION; WALT DISNEY PICTURES/EVERETT COLLECTION

Maybe the thought first occurred to you during the end of March, when a graceful, modern update of a Shakespearean comedy and a groundbreaking science-fiction movie opened on the same weekend. Or perhaps it was the wave of summer releases that hit screens, from the single most anticipated blockbuster ever to Stanley Kubrick’s swan song, that made you think something special was starting to happen. Or it could have been the tsunami of zeitgeist-surfing movies — all from a generation of filmmakers who, having come out of the Sundance labs and/or cut their teeth on music videos, would resurrect the maverick spirit of the Seventies auteurs — that convinced you that 1999 wasn’t just shaping up to be a pretty good year at the movies. It was turning into a genuinely great year at the movies.

In fact, after the Golden Age apex of 1939 and the New Hollywood highlight of 1974, the last gasp of the Nineties is now considered to be one of single best 12-month stretches of American moviemaking ever. Add in the number of international films that were finally making their ways to our screens during those 12 months, and it would turn out to be a banner annum for American moviegoing as well. Not to mention that the lineups at both Cannes and Venice would earmark this as a standout year for the festival circuit as well. Thanks to a perfect storm of talent, timing, and taste, 1999 would quickly be viewed as a major milestone for the medium. And a quarter of a century later, it only looks that much more like a pinnacle.

So, in honor of the 25th anniversary, we’ve ranked the top 99 movies of 1999 — the best of the best, the box-office stand-outs, the big-name blockbusters, the brilliant indies and foreign-language landmarks, the bold documentaries, and a few of the batshit cult-movie outliers that helped define a truly outstanding year to be a movie lover.

A quick note about our selection process: For better or worse, we’re going by both release dates tied to a movie’s theatrical run in America *and* film festival premiere dates. So, for example, you’ll see Audition, Ghost Dog, Ratcatcher and Beau Travail here, even though each of these extraordinary works didn’t officially grace American screens for a week or longer until 2000. Yet you will also see a few leftovers from previous years, such as Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels, Princess Mononoke and Run Lola Run, since they didn’t get full U.S. releases until 1999. (There’s one notable exception, which we’ll single out below.)

CONTRIBUTORS: Jon Dolan, A.A. Dowd, David Fear, Maria Fontoura, Tim Grierson, Rob Sheffield

From Rolling Stone US

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.