Todd Haynes remembers walking into a record store in L.A. — it would have been some time around 1974, when he was about 13 years old — and seeing the cover for David Bowie’s “Diamond Dogs.” The image of the future Thin White Duke staring out at him “completely scared me, freaked me out,” says the Portland, Oregon-based filmmaker. “But a part of me was like, ‘This is my future.’ It’s that feeling you get when you come across something that you somehow know will eventually change your life, right at the moment before you’re ready to receive it.” He recalls having that same feeling upon discovering Roxy Music, and hearing punk rock, and watching experimental short movies from the Sixties, all of which similarly scrambled his DNA.

Haynes couldn’t tell you exactly when the music of another band came across his radar, the group that would bridge the gap between the Brill building, Baudelaire, and downtown New York bohemianism. He was sure he saw posters for the “banana album” around, and had probably heard their name once or twice; he knows he’d heard singer Lou Reed’s solo stuff before he got to college. The only thing he distinctly remembers upon hearing the Velvet Underground’s music for first time was the sense that he’d stumbled across the Rosetta stone for everything that had spurred his creativity and the culture that inspired him. “I’d already been immersed in punk and glam and New Wave, and it was the sense that, ‘Oh, this is all this music I’ve been listening to for years in one band,‘” he says. “You know, that joy you get when discover the common denominator. I’d felt like I’d found the source. I’d found the epicenter.”

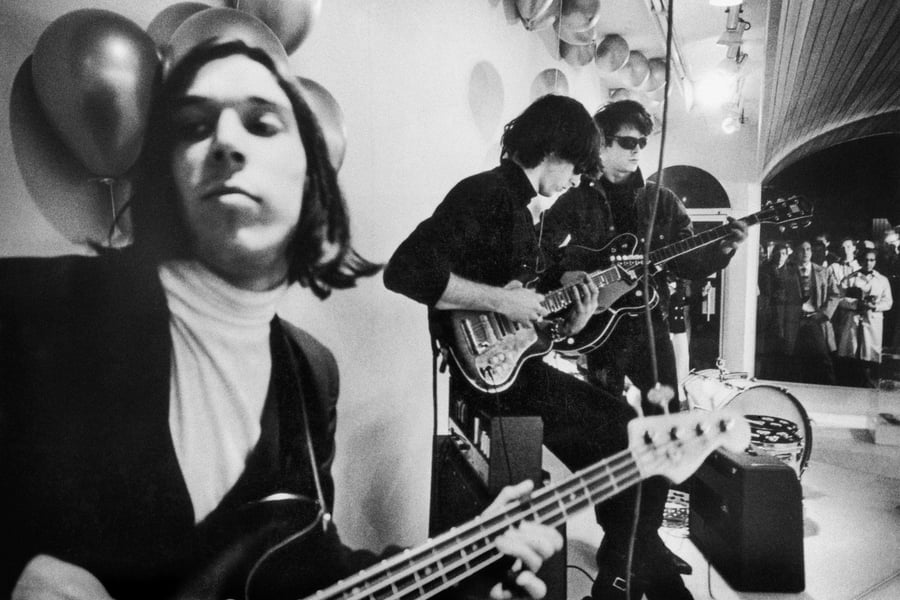

It’s said that everyone who saw the Velvet Underground went out and started their own band. In a perfect world, everyone who sees The Velvet Underground (which opens at New York’s Film Forum on October 13th, and premieres on Apple TV+ October 15th), Haynes’ extraordinary look back at the seminal New York band, would not only start their own group but also pick up a camera. The first documentary from the director of the glam-rock time capsule Velvet Goldmine (1998) and the many-sides-of-Bob-Dylan biopic I’m Not There (2007), it includes archival footage, behind-the-scenes anecdotes, and interviews with Velvets co-founder John Cale, drummer Maureen Tucker, and many surviving collaborators.

But Haynes also borrows from the same sources that inspired the transgressive group — avant-garde cinema, pop art, various Sixties’ subterranean subcultures, rock & roll rebelliousness — in telling the story of the Velvets’ brief career, from their time as Andy Warhol’s house band at the Factory (he was also briefly the band’s manager) to their eventual flameout a few years later. From the moment the film sets up Cale and Lou Reed coming together via split screen, a perfect homage to Warhol’s film Chelsea Girls, you get that this is a singular, experimental look at a singular, experimental band.

“I felt we didn’t need a movie about the Velvet Underground that simply said how great they were; there are tons of critics who can tell you that,” Haynes says. “I wanted to honor them but, in the spirit of the group, do something radical. And to try and figure out how three wayward kids from Long Island, a Welsh avant-garde musician, this strange German model and a shy, pockmarked second-generation Lithuanian come together at this one key moment.”

The notion of diving into a portrait of doing a group, much less doing a music documentary, had never really occurred to the filmmaker. But in 2017, Haynes found himself honored at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, alongside musician Laurie Anderson. The two hit it off; as it turns out, she had just given the L.A. Public Library her late-husband Reed’s archives. When producers subsequently approached her about a portrait of the Velvets, she suggested Haynes. Despite the fact he’d never made a doc, he was immediately interested.

Todd Haynes at the premiere of ‘The Velvet Underground’ during the 74th Cannes Film Festival in July. (Photo: P. Lehman/Barcroft Media via Getty Images)

The filmmaker quickly set down a rule: For interviews, Haynes only wanted people who were there, or who personally knew Reed, the German model/chanteuse Christa Päffgen — better known by her stage name, Nico — and late guitarist Sterling Morrison. Cale was one of the first to sign on. (“I considered almost everything that Todd [has] made the work of a ‘safe pair of hands,’ ” he says via email, adding that Haynes’ participation was the difference “between carnivorous attention and the unconscious pursuit of beauty.”) Bassist-organist-vocalist Doug Yule, who joined the band for its third album, declined to participate — “He’s an environmentalist, and I think he felt there were other urgent matters that needed his attention,” Haynes says — but Modern Lovers singer and press-shy superfan Jonathan Richman sat for a rare on-camera conversation. “He saw 60 to 80 shows of theirs in Boston and got to know them as a teenager,” Haynes says. “You would have thought that the Velvet Underground would have just laughed him out of the room. And instead, they taught him how to play guitar.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

After talking to the principals and witnesses, Haynes immersed himself in the explosion of art that was happening around the Velvets as they started to craft their dark, droning sound (what Cale calls “equal parts Bo Diddley and Aaron Copland”). Not just Warhol’s subversive, superstar-driven projects, but the work of filmmakers Jonas Mekas and Jack Smith, composers La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, and a host of others creating art in downtown Manhattan’s avant-garde-friendly ecosphere. “I knew I wanted to tell that story through the late-Sixties’ experimental vernacular,” Haynes says. “There was a crossing of boundaries at the time from mainstream to marginal, from underground to commercial. I thought, ‘Let’s make a film that isn’t an oral history. Let’s make one where the music and the images lead us, not the words.’ ”

The result feels like a movie that might have screened next door to one of the Velvets’ Plastic Inevitable performances, or like Warhol’s famous film of the band, which he projected over them while they played — a beautiful riot of cacophonous sounds, colliding visuals, clips of the band at its height, and testimonials that put everything into a 360-degree context. The Velvet Underground feels, in other words, a lot like one of the band’s albums, where the combination of contrasting elements come together to form something poetic and perverse.

“Honestly, even if their music didn’t completely get inside me, I would have wanted to make a movie about them,” Haynes says. “It’s that whole era, which was so revolutionary, but it’s also what they were trying to do as well in reaction to that era as well. Even in their little world, they were heavy. It’s about being resistant. It’s saying no. That’s so important to rock & roll.”

From Rolling Stone US