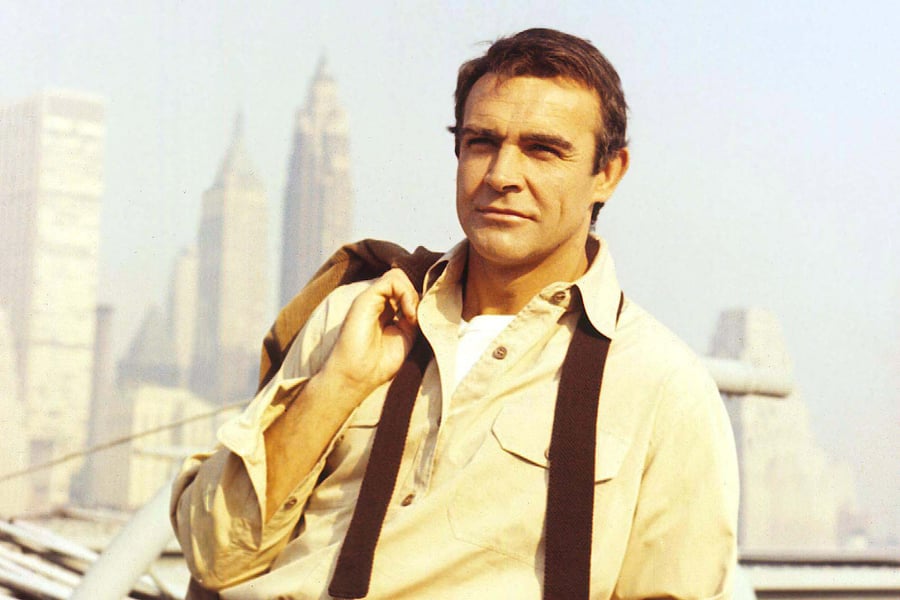

Let’s raise a farewell glass to one of the all-time greats, Sean Connery. Even though the legendary Scottish actor turned 90 this summer, his death still feels like a shock, just because Connery seemed like he’d stick around forever — a giant oak towering over other stars, showing them up as lightweights. The most charismatic of movie stars, all craggy gravitas, with zero interest in celebrity, sucking up to nobody, Connery held a simple code and lived by it. As he told Rolling Stone in a 1983 cover story, “The lesson there is, keep your mouth shut and your front door clean.”

Connery really came from another world: the last generation of actors who grew up hungry in World War II, a working-class Edinburgh kid raised in urban slums with no indoor plumbing, dropping out of school at 13 and going to work in a string of dirty jobs. Yet he got famous playing James Bond, the ultimate posh and debonair English sophisticate. You could stick him into any movie, no matter how cheesy, and he brought a little dignity to it. He even managed to get away with playing King Arthur in a 1995 fantasy drama called First Knight, directed by Jerry Zucker of Airplane! fame, starring Richard Gere as Lancelot and Julia Ormond as Guinevere. The movie might be terrible, but Connery was worth watching, and he always walked away with all his mystique intact. You always felt like you were seeing the last real movie star.

He blew up as the definitive James Bond — from 1961’s Dr. No to 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever, with a return in 1983 with Never Say Never Again. He brought his own surly edge to Bond, dashing but unsmiling, a spy licensed to kill. His 007 seemed to take no joy in his black-tie boozing and womanizing; it was all in the line of duty, for queen and country. Connery was the grumpiest, moodiest Bond, grimacing in pain at the jokes he had to deliver. A classic moment, in From Russia With Love, when he finds out a fellow agent is a KGB assassin posing as an upper-crust Brit: Connery rolls his eyes and says, “Red wine with fish. That should have told me something.”

The irony: James Bond, the elite son of Eton and Sandhurst, was played by a poor Scottish tenement kid. Like so many of the movies’ favorite British gentlemen — Cary Grant for one — Connery was a street hustler who learned to turn on the charm for the camera. He always had that famous “Scotland Forever” tattoo, which he got as a teenager in the Royal Navy in the Forties, long before it was thinkable for a respectable movie star to get ink. “The war was on, so my whole education time was a wipeout,” he says. “I had no qualifications at all for any job, and unemployment has always been very high in Scotland anyway, so you take what you get. I was a milkman, laborer, steel bender, cement mixer — virtually anything.”

He took up body-building and acting, which were not unrelated for him, and moved to London for a Mr. Universe competition. (He came in third.) He got his big break when he caught the eye of Lana Turner, 10 years his senior; she chose him to play her lover in the flop melodrama Another Time, Another Place. (Connery fled L.A. to avoid getting bumped off by her mobster boyfriend.) He also starred in the Disney movie Darby O’Gill and the Little People, a profoundly creepy kiddie flick abut psycho leprechauns.

But Connery finally became a star in Dr. No, with Ursula Andress as his beach-bunny muse, Honey Ryder. As “Bond, James Bond,” his bitchy pout got nastier with each 007 movie, from Goldfinger to Thunderball, from You Only Live Twice (where he beats up the Rock’s real-life grandfather) to Diamonds Are Forever (where his Bond girl is Henry Kissinger’s real-life side-piece).

Only Connery could have made Bond so convincing, given how the fantasy was so out of sync with the real world. There was something ridiculous about an English spy fighting a Cold War that nobody else seemed to notice England was even invited to join. (What, the Brits were planning to invade Connecticut?) At a time when that country’s greatness consisted mainly of cranking out pop stars and inventing miniskirts, Bond was the last man defending the honor of a British Empire that no longer existed. Yet he seemed to believe the Russian troops would spill into Croydon and Shaftesbury and Wakefield the minute he let down his guard or settled for a stirred-not-shaken martini. That was the joke implicit in his code name 007 — the idea that there were at least six more of these delusional jokers running around the world.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

Sean Connery called the 007 role “a Frankenstein’s monster,” one he fought hard to escape. “I’d been an actor since I was twenty-five,” he told Rolling Stone. “But the image that the press put out was that I just fell into this tuxedo and started mixing vodka martinis. And, of course, it was nothin’ like that at all. I’d done television, theater, a whole slew of things. But it was more dramatic to present me as someone who had just stepped in off the street.” Eager to prove himself as a real actor — see the 1964 Hitchcock thriller Marnie, with Tippi Hedren — he left Bond behind for bigger challenges. Connery could have spent the rest of his life as 007, but he became himself instead.

He really became “Connery, Sean Connery” in the mid-Seventies, with a trilogy of adventure films about middle-aged rogues: The Man Who Would Be King, The Wind and the Lion, Robin and Marian. He stopped wearing his 007 hairpiece, yet it just cranked up his charisma — as Pauline Kael wrote, “If baldness ever needed redeeming, he’s done it for all time.”

In his forties, the star suddenly seemed larger, louder, more swaggeringly himself than ever. He’s poignant in Robin and Marian, as a washed-up Robin Hood back in Sherwood Forest, reunited with Audrey Hepburn’s Maid Marian. But he’s even better in The Man Who Would Be King — his fiercest performance ever, and the role of a lifetime. In John Huston’s film of the Rudyard Kipling story, Connery and his real-life friend Michael Caine play a pair of English con men in 1880s India. They make a perfect criminal team, lighting each other’s cigars or marching in step, devising a crazy scheme to take over a small country and pose as divine rulers. Connery’s Danny Dravot is the most dangerous kind of criminal: a mystic scoundrel who can’t resist falling in love with his own lies.

These movies weren’t hits, but they defined Connery as the world came to know him, in grand-old-man mode. He was always in demand after that, in good movies or bad: Highlander, Time Bandits, Cuba, Outland, The Rock, Zardoz (the 1974 dystopian thriller with the tag line, “I have seen the future and it doesn’t work”), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (as father to Harrison Ford, a mere 12 years his junior). He won an Oscar in 1987 for The Untouchables, playing a cynical Chicago cop with a vigor and humor that blazed off the screen. For the first time in his career, pushing 60, he was bigger than Bond. Only one man ever outsmarted 007, and it was Connery.

He appeared in plenty of flimsy movies, but always as himself. Connery had the same feisty attitude Neil Young brought to playing with Crosby, Stills, and Nash: Don’t join the tour, just show up for the gigs. You could go see him in anything and know you’d get that signature gravitas. He teamed up with Wesley Snipes to kick the yakuza’s ass in the awesomely ridiculous 1993 thriller Rising Sun, lecturing Snipes on the fine points of Japanese culture. In the 1999 heist caper Entrapment, he played a suave master thief — the kind who could exist only in Connery movies — cavorting with Catherine Zeta-Jones, who was born in between You Only Live Twice and Diamonds Are Forever. A less assured actor would have looked downright silly in these movies: self-parodic, even a bit sad. Yet Connery held his own.

Darrell Hammond captured the Connery charisma on SNL’s recurring “Celebrity Jeopardy” sketches, baiting Will Ferrell’s Alex Trebek. But Ferrell did him one better, turning his own Connery imitation into Anchorman, where his Ron Burgundy yells things like “Great Odin’s raven!” or “By the beard of Zeus!” (He’s parodying the Connery of The Man Who Would Be King, whose favorite expletive is “God’s holy trousers!”)

Connery was knighted by the Queen in 2000, after considerable controversy, since he was the world’s most outspoken Scottish nationalist. His final movie was The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, in 2003. He never became a joke, never looked ridiculous, never let himself get miscast. Fanatical about privacy and golf, surprisingly married to the same woman for the past 45 years (talk about off-brand), he retained his sense of humor to the end, as well as his cranky independence. We won’t see his like again. So here’s a toast to Sean Connery — shaken, not stirred.

From Rolling Stone US