He was a Hollywood golden boy and the Sundance kid, the missing link between The Twilight Zone (check out the towheaded 25-year-old playing the Prince of Darkness) and the Marvel Cinematic Universe. An actor-turned-director who helped everybody from Scarlett Johansson to Brad Pitt become household names. A film festival founder who helped several generations of moviemakers find their voices, and provided the primary platform for the American independent film movement. An activist who stumped for environmental causes long before it was chic, a celebrity who took political stances long before it was expected (or derided), a tireless advocate for the less fortunate, a lifelong skier, and, as he told me the last time I interviewed him, a lover of fine tequila.

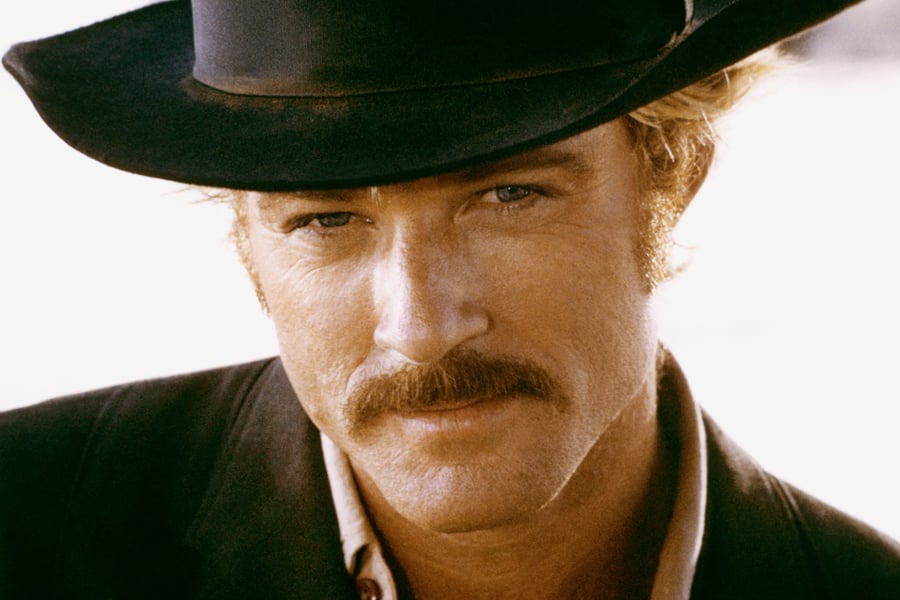

For most of us, however, Robert Redford, who died today at age 89, was simply the definition of a movie star. You expect a picture of him from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, his head cocked, his blue eyes glowing, his blond hair peeking out of his black cowboy hat, to be next to the dictionary listing for the term. From the late 1960s until the early 1980s, when he started splitting his time in front of the camera and behind it, Redford was not just an extraordinary leading man and a major box-office draw. He was the movies, in all of their escapist and ennobling glory.

A California native who long called Utah home, Redford grew up as what he termed a “juvenile delinquent” in Los Angeles before getting a baseball scholarship to a Colorado University. After getting kicked out, he wandered around Europe and ended up in Brooklyn to study painting. Once Redford switched his attentions to acting, he’d barely graduated from the American Academy of Dramatic Arts before he started booking theater gigs and the occasional television role in shows like Route 66 and Alfred Hitchcock Presents. In later years, he often expressed frustration with his limited abilities when he was starting out, and felt that he couldn’t cut it against the “serious” actors of the day, the Montgomery Clifts and Marlon Brandos everyone held up as the moody, Method-y pinnacle of the form. But Redford was already cultivating a presence — an ability to make you watch him even if he was in the background. When he finally did act against Brando, in Arthur Penn’s Southern-fried melodrama The Chase (1966), the juvenile delinquent from Santa Monica more than held his own.

Part of it was that lived experience, which allowed him to add a pinch of salt to his smooth operators and young up-and-comers. And part of it was that face, the sort of Adonis-like mug that tips the scales from handsome to outright pretty. Redford knew how to use his inhumanly good looks to great effect onscreen, either as a way of drawing someone in, sometimes deceptively so (see: Inside Daisy Clover, Downhill Racer, The Candidate, The Sting), or of sweeping a woman off her feet. The oft-told anecdote about the actor, who’d already turned heads in Barefoot in the Park, going after the coveted lead in The Graduate, says it all. Mike Nichols, who’d directed Redford onstage in the original Broadway production of Barefoot, told his friend that he was all wrong for the part of Benjamin Braddock. “When was the last time you struck out with a lady?” the director asked Redford. “What do you mean?” the actor replied, genuinely confused. Point proven.

There were a lot of photogenic profiles in Hollywood in the late 1960s, however. Redford stood out because he knew how to combine those looks, along with his collegiate athlete’s physique, and an innate sense of honor into something that simultaneously felt contained and combustible when filtered through celluloid strips. The camera loved him. So did audiences, who sensed that this golden boy was also a decent man.

It’s why they bought his rascally double-act with his real-life friend Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1973), a.k.a. the bromances that launched a thousand masculine buddy comedies. It’s also why he could play an idealist ground up in the electoral system in The Candidate (1972), an obscure object of desire in The Way We Were (1973), an innocent analyst caught up in C.I.A. shenanigans in Three Days of the Condor (1975), and white-knight characters like Bob Woodward in All the President’s Men (1976) or the rodeo champ who stands up for animal rights in The Electric Horseman (1979). Watch how he turns a scene involving the Watergate reporter taking a phone call from a source into a three-act play. He makes wonky investigative journalism the sexiest and most righteous occupation on the planet.

That translated into Redford’s offscreen activism as well, whether it was politically or environmentally based. He may have been an early prototype of the Modern Hollywood Liberal, scourge of those who felt that famous people like him should simply do the movie-star equivalent of shut up and dribble. But Redford did the research and walked the walk. He stood up for a number of candidates and causes when it was risky to do so, like opposing a coal-based power plant in Southern Utah in 1976.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

And when Redford started directing films instead of just starring in them full-time, he took his need to draw attention to social causes with him. His debut, Ordinary People (1980), is a straightforward character piece that favors its literary source material and its performers; you can tell an actor is calling the shots, which didn’t stop the rigorously put-together drama from winning the Best Picture Oscar. But he followed that up with The Milagro Beanfield War (1988), which pitted Latino farmers against real-estate developers; A River Runs Through It (1992), an adaptation of Norman Maclean’s novel that let an undercurrent of environmental concern run under it; Quiz Show (1994), which turned the Twenty-One TV quiz scandals into a parable about morality and the media; and various other civically informed movies, from Lions for Lambs (2007) and The Conspirator (2010). He still lent out his movie-star persona and gravitas to other directors — this is the era of The Natural (1984), Out of Africa (1985) and Indecent Proposal (1993), all fodder for greatest-hits reels — but he embraced the idea of being a more hands-on storyteller as he got older. You can feel him passing the golden boy torch onto guys like Pitt. (This conversation between those two stars during a tribute at Telluride, by the way, is priceless.)

And then, on the sixth day, the lord Bob created Sundance — and it was good. Having settled in Park City, Utah, Redford became heavily involved with the Utah/U.S. Film Festival, which had moved from Salt Lake City to the ski resort town in 1981. He eventually helped transform the modest little event into what would later be redubbed the Sundance Film Festival, named after his outlaw character. He also oversaw operations of the Sundance Institute, which brought seasoned industry veterans out to Park City in order to mentor fledgling screenwriters and directors and help them develop projects. As a formative laboratory for the next generation of filmmakers, it was peerless and invaluable. Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson came through here. So did Taika Waititi, Richard Linklater, Lulu Wang, Ryan Coogler, Sterlin Harjo, and dozens of other major players. Its focus on indigenous filmmakers was especially unique. These twin totems of American indie film remain a huge part of Redford’s legacy, not to mention an ode to his commitment to fostering the future of the medium. For years, you’d see him wandering around the festival, sometimes providing long introductions to screenings and other times simply milling on the sidelines, content to let the next crop fill the spotlight.

Yet it’s Redford the star that comes to mind first and foremost as we say goodbye to him today — still the guy who smiled onscreen and made hearts flutter, still the guy jumping off the cliff with Butch (“I can’t swim!”), still the guy who made you think that good people still walked the earth and sought to protect it. Your mind might immediately go to the early-years Redford, or the heyday Redford of the 1970s, or even the middle-aged Redford who gave projects a sense of gravitas. For us, this scene from his last big screen role, in David Lowery’s extraordinary, elegiac The Old Man and the Gun (2018), says it all. It’s just a career criminal in his winter years, enjoying a car ride and having a conversation with Sissy Spacek’s widow over lunch. And in Redford’s hands, you get an entire life in a single, long exchange. He was one of a kind.

From Rolling Stone US