Christopher Russell owned a small bar in Chesapeake Beach, Maryland, but, like a lot people these days, figured he had better odds hooking up online. Russell was 40 and going through a divorce, so he wasn’t seeking anything serious. When he saw an ad for the dating site Ashley Madison, which boasted 36 million members and the tagline, “Life is short, have an affair,” he decided to check it out. “It seemed like a very active community,” he says.

Russell was soon browsing rows of enticing women. Shortly after creating his account, he got an alert that one of them had viewed his profile. Her picture, however, was blurred. In order to see more details and contact her, he had to buy credits. Everyday, he received more of these come-ons — until he finally said, “Fuck it.” “I’m like, ‘Hey, all these women want to talk with me,'” he recalls. “‘Let me go ahead and put in my credit card information.'”

Russell paid $100 for 1,000 credits, which he could spend on sending replies or virtual gifts. But the experience was increasingly disappointing. Women who hit him up wouldn’t reply back. As anyone who’s dated online knows, this is not entirely unusual. People flirt then vanish for no apparent reason. “I just figured they’re not interested anymore,” Russell says. After a few months of rejection, he didn’t bother to log back on Ashley Madison again.

Last July, he found out that he wasn’t the only one getting the silent treatment. A hacker group called The Impact Team leaked internal memos from Ashley Madison’s parent company, Avid Life, which revealed the widespread use of sexbots — artificially-intelligent programs, posing as real people, intended to seduce lonely hearts like Russell into paying for premium service. Bloggers poured over the data, estimating that of the 5.5 million female profiles on the site, as few as 12,000 were real women — allegations that Ashley Madison denied.

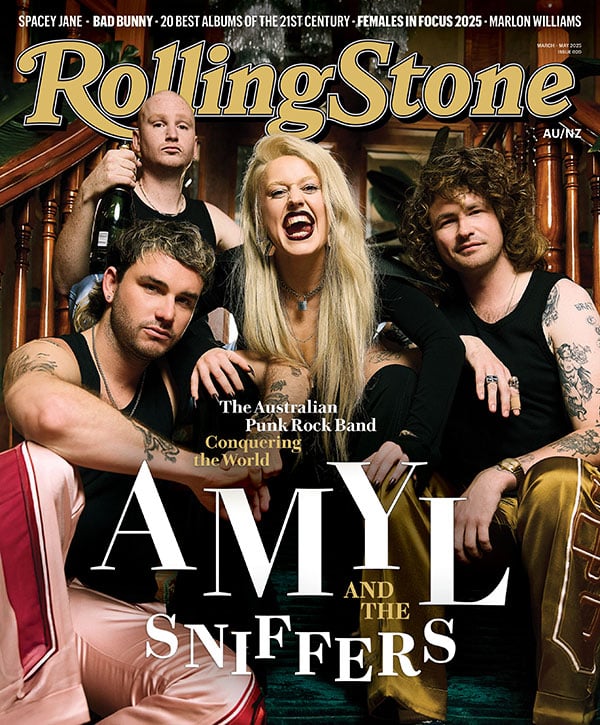

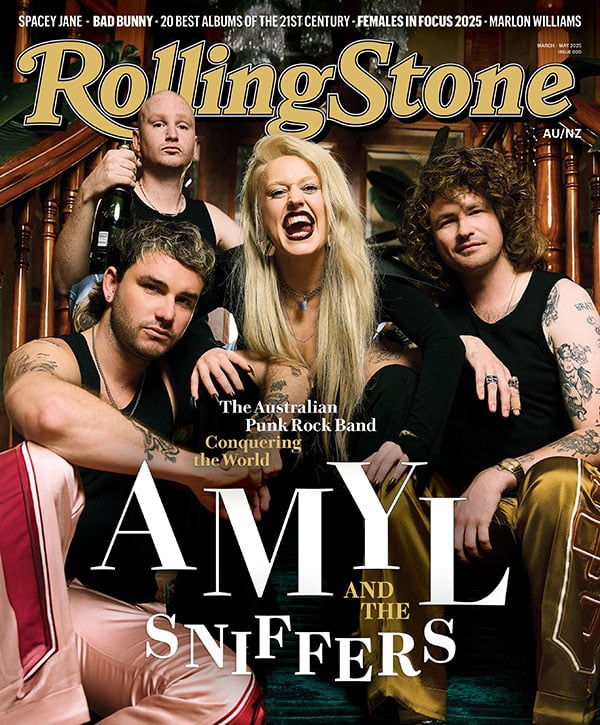

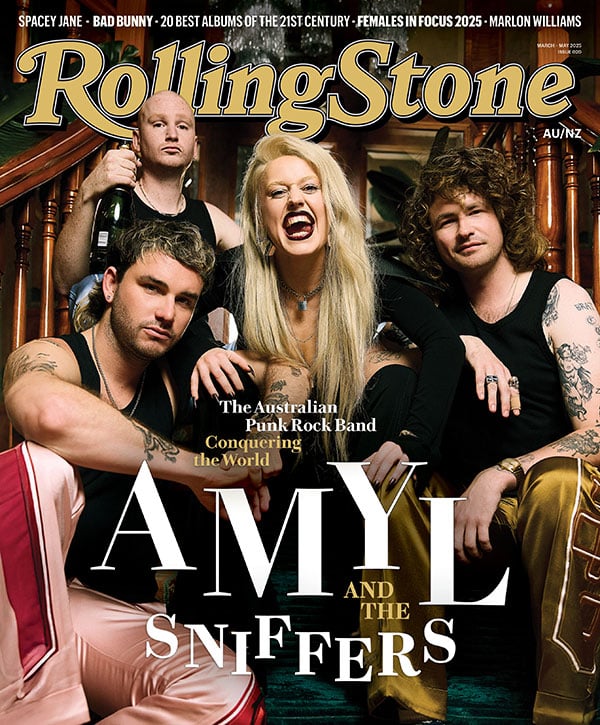

To get new visitors to pay for memberships, the adultery dating site, Ashley Madison, deployed bots called “Ashley Angels.” Illustration by Brittany Falussy

A whopping 59 percent of all online traffic — not just dating sites — is generated by bots, according to the tech analyst firm, Are You a Human. Whether you know it r not, odds are you’ve encountered one. That ace going all-in against you in online poker? A bot. The dude hunting you down in Call of Duty? Bot. The strangers hitting you up for likes on Facebook? Yep, them too. And, like many online trends, this one’s rising up from the steamier corners of the web. Bots are infiltrating just about every dating service. Spammers are using them to lure victims on Tinder, according to multiple studies by Symantec, the computer security firm. “The majority of the matches are often bots,” says Satnam Narang, Symantec’s senior response manager. (Tinder declined to comment).

Keeping the automated personalities at bay has become a central challenge for software developers. “It’s really difficult to find them,” says Ben Trenda, Are You Human’s CEO. “You can design a bot to fool fraud detection.” But, in the case of a number of dating sites, developers aren’t trying to weed out fake profiles — they are tirelessly writing scripts and algorithms to unleash more of them. It’s the dirtiest secret of the $2 billion online dating business and it stretches far beyond Ashley Madison. “They’re not the only ones using fake profiles,” says Marc Lesnick, organizer of iDate, the industry’s largest trade show. “It’s definitely pervasive.”

I have to to be careful of what I say,” Andrew Conru, the founder and owner of Adult Friend Finder, tells me one morning in his corner office high above San Jose. A lanky, 46-year-old, who holds a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering design from Stanford, Conru is among the smartest and most respected people in the online dating business. Since he launched AFF in 1995, he’s turned the site into a swinger-friendly empire that’s discreetly mainstream — boasting over 30 million members who pay $10 a month to find “sex hookups, online sex friends or hot fuck friends.” But while Conru has enough millions to retire several times over, he’s giving a rare interview to blow the whistle on the widespread use of sexbots in the business. “The only way you can compete with fraud is you let people know it’s fraud,” he tells me. “And it happens across the industry.”

Conru and AFF’s CEO, Jon Buckheit, another Stanford Ph.D., boot up the site of a top competitor, Fling, and demonstrate how, shortly after registering, they are wooed by what appear to be bots. With a Google image search, one of the women turns out to be pornstar Megan Summers. “She wants to see your photos?” Buckheit asks, in disbelief. “We doubt it really is Megan Summers.”

In an email, Fling owner Abe Smilowitz writes, “We absolutely don’t use fake profiles and bots…Us and AFF are pretty much the only guys that don’t.” This could be true. Any number of spammers and hackers might have created the profile with Summers’ photo; it could be a housewife using the likeness to boost her appeal or conceal her identity. Buckheit shrugs at the suggestion. “They disclaim using bots,” he says. “We still think they do.”

To keep out the bots of spammers and hackers on AFF, Conru, who launched the site shortly after getting his doctorate as a means to meet women, codes his own countermeasures and frequently checks user names and IP addresses for veracity. “It’s a daily slog, going through hundreds of accounts every day evaluating them and deactivating them,” he says. “It’s been a cat and mouse game for 20 years.”

And it’s not a game he always wins. The company suffered a massive hack that exposed the profiles of an estimated 3.5 million members — which generated international headlines by revealing high-profile kink-seekers on Capitol Hill, in Hollywood and higher education. “I don’t know if I can disclose this,” Conru says, “but recently, I had a guy do a search to see, like, WhiteHouse.gov, and we found that there are lots of .govs, and a lot of .edus.”

Automated filters determined how Angels engaged with visitors — direct chats were often sent to guests, while “winks” and other messages were sent to the inboxes of members. Illustration by Brittany Falussey

The company incentivizes members to prove they’re who they say they are by sending in copies of their drivers licenses in return for a “verified” button on their profiles (similar to the little blue checks on Twitter accounts). The fact that men outnumber women on the site’s heterosexual platform ten-to-one is just life, they figure, and the women on the site are seemingly active enough to keep the guys onboard. For AFF, bots are a cop out, though the appeal of building them is obvious enough to Conru. “If I wanted to boost our revenue and move to the Cayman Islands, we could probably double our revenue simply by using bots,” he says. “And our bots would kick ass.”

The fact that AI con artists are up to such tricks isn’t surprising or new. But what’s truly phenomenal is the durability of this online hustle, and the millions of saps still falling for it. “A lot of people think this only happens to dumb people, and they can tell if they’re talking to a bot,” says Steve Baker, a lead investigator for the Federal Trade Commission tells me. “But you can’t tell. The people running these scams are professionals, they do this for a living.”

The scam starts with creating a chat bot, which is easier than you’d think. Bot software is freely available online. The Artificial Linguistic Internet Computer Entity, or ALICE, which generates scripts for chatterbots, has been around for decades. These programs can be modified for any purpose, though designing a believable online dating companion can take considerable time and effort — perhaps too much for some of the troops at Ashley Madison.

In 2012, Doriana Silva, a former Ashley Madison employee in Toronto, sued Avid Life Media for $20 million complaining that she suffered from repetitive strain injury while creating over 1,000 sexbots — known within the company as “Ashley’s Angels” — for the site. The company countersued Silva, alleging that she absconded with confidential “work product and training materials,” and posted pictures of her on a jet ski to suggest she wasn’t so injured after all. (Both sides agreed to drop the suits early last year.)

Despite the controversy, the company subsequently attempted to streamline its bot-creation process. Internal documents leaked during the Ashley Madison hack detail how, according to a 2013 email from managing director Keith Lalonde to then-CEO Noel Biderman, the company improved sex machine production for “building Angels enmass [sic].” This was done, Lalonde wrote, because the staff was getting “writers block when making them one at a time and were not being creative enough.” (Reps for Ashley Madison did not return requests for comment).

According to leaked emails, to create the bots, the staff utilized photos from what they described as “abandoned profiles” that were at least two years old. They also generated 10,000 lines of profile descriptions and captions. A leaked file of sample dialogue includes lines such as: “Is anyone home lol, I’d enjoy an interesting cyber chat, are you up to it?” and “I might be a bit shy at first, wait til you get to know me, wink wink :)”. Bots were deployed for international markets as well. The company would simply run the dialogue lines through translate.com. In the end, about 80 percent of paying customers were contacted by an Ashley Angel.

“It appears they were scamming their users,” Conru says.

Sex bots don’t even have to be that good to do their job. These aren’t being created to pass the Turing Test, the legendary challenge named after artificial intelligence pioneer Alan Turing which aims to convince a human she’s talking with another person and not a machine. Their sole purpose is to get the dater to want to chat more. And a pent-up dude online is the easiest mark. As acclaimed AI researcher Bruce Wilcox puts it, “Many people online want to talk about sex. With chat bots, they don’t require a lot of convincing.”

By the time of last summer’s hack, the site had created more than 70,000 female bots that sent millions of fake messages to paying customers. Illustration by Brittany Falussy

By the time of last summer’s hack, the site had created more than 70,000 female bots that sent millions of fake messages to paying customers. Illustration by Brittany FalussyLuckygirl wants to chat. Her request pops up on my screen shortly after I create a free account on UpForIt, a popular hookup site that bills itself as the place “where hotties meet.” Luckygirl fits the criteria. Her profile shows a pretty, tanned 32-year-old from New York, with chestnut hair in a perky ponytail and a zebra-striped halter-top.

Whether I qualify as a hottie is impossible to say, because I haven’t uploaded a picture or description yet. But Luckygirl is eager to party, so I click reply. A window pops up telling me that in order to read her message I have to upgrade to a premium membership for a variety of fees. Ok, fine, I whip out my card and opt for the cheapest deal, $1.06 per day for three days. When my transaction is approved, I read the fine print warning me that any reversed charges could result in me being “blacklisted” from credit card processors.

With swingers like Luckygirl on the prowl, who’s going to complain? Unless, of course, the prowlers are fake — which seems to be the case once I pass the paywall (as if a supermodel hitting up an anonymous guy online isn’t tipoff enough). Within seconds, I’m pinged by a Kardashian lookalike who messages that she’s “feelin FRISKY and NID sme0ne to plaay with.” Then there’s Ruthdonneil123, a 33-year-old New Yorker whose profile picture, I discover by a Google Image Search, is, in fact, a stock picture of a pornstar.

So that’s how the hustle basically works: get a guy on a site for free, flood him with sexy playmates who want to chat, then make him pay for the privilege. Along the way, hit him up to join a webcam site, or maybe a porn site. Oh yeah, and then put some mandatory memberships in the fine print which automatically renew each year. And of all the guys who get roped in, how many are going to report to their credit card company that they were trying to have an affair online?

A representative for UpForIt didn’t return a reply for comment. But Lesnick, the iDate organizer, says there’s no doubting who’s up to such tricks. “Everyone in the industry knows who the good players are and who bad players are,” he says. “Eventually the bad guys will get found out and get caught. This is fraud.” But when I ask him to name names, like many in the business, he declines. “I have to bite my lip,” he says. “Some of them come to my event.”

In October 2014, the Federal Trade Commission took its first law enforcement action against sexbots when it fined JDI Dating, a UK-based owner of 18 dating sites including flirtcrowd.com and findmelove.com, $616,000 for assailing members with phony profiles. Though JDI labeled the sexbots’ profiles as “virtual cupids,” the FTC found this and other practices, such as automatic rebilling practices, to be deceptive.

And yet, even at JDI, the sexbots march on. Flirt Crowd’s homepage notes that, “This site includes fictitious profiles called ‘Fantasy Cupids’ (FC) operated by the site; communications with a FC profile will not result in a physical meeting.” By joining, subscribers accept that “some of the profiles and Members and/or Subscribers displayed to them will be fabricated.” JDI did not return requests for comment, but the owner, William Mark Thomas, consistently denied the FTC’s allegations elsewhere, despite the settlement.

They aren’t the only ones sneaking sexbots into the fine print. Similar language appears on UpForIt, which says the company creates user profiles so visitors can “experience the type of communications that they can expect as a paying Member.” In fact, for all the outrage over Ashley Madison’s fake femmes, the company had been disclosing its use of “Ashley’s Angels” for years in its own Terms of Service as an “attempt to simulate communications with real members to encourage more conversation.” Today, that language is gone, but there’s still a clause with wiggle room: “You agree that some of the features of our Site and our Service are intended to provide entertainment.”

Obviously, the sites don’t want to draw attention to the fine print. In January, Biderman, Ashley Madison’s former CEO, emailed staff members under the subject line “this is really problematic…” He pointed out that the Wikipedia entry on Ashley Madison had been changed to include a section on Ashley’s Angels. In response, Anthony Macri, the former director of social media for Avid Media Life, assured Biderman he would remedy the problem. “I will change it back to what it was,” he replied. Biderman suggested tweaking it to read, “The sites authenticity has been challenged and proved to be legitimate.”

In the meantime, Christopher Russell, the club owner jilted by Ashley Madison bots, is now part of a class action suit against Ashley Madison. As a matter of principal, he wants his $100 back, and for the government to establish new rules for the multibillion-dollar playfield. “I hope this puts all of the dating sites on notice that this kind of behaviour is fraudulent,” he says. “You shouldn’t be tricking people on your site into handing over money when nobody is on the other end of it.”

There’s a counterintuitive way to look at the success of AI cons on the Net, as well as the present and future status of bots online: all the people who got duped wouldn’t have been so dupable if they weren’t enjoying themselves, right? Bot or no bot, the encounters were giving them pleasure. It’s the same logic that applies to strippers chatting up guys for cash, or the so-called “hostess bars” in Tokyo where guys pay not for skin at all but conversation. Likewise, Tinder’s “It’s a Match” screen can offer as much of a Pavlovian fix as any IRL meet up.

Ashley Madison’s own research found that about 80 percent of visitors who became paying customers were contacted by its Angels. Illustration by Brittany Falussy

Maybe, in the future, when online daters are jacking in and jacking off in the Matrix, they won’t care who or what is on the other end. Maybe they already don’t care. Plenty of people just want some kind of customizable, convincing experience to get turned on. Facebook’s $2 billion acquisition of Oculus Rift, the leading virtual reality firm, is one big clue that simulated life online is about to get exponentially immersive — making it even more difficult to distinguish real people online from bots.

We’re still decades away from a Scarlett Johansson bot, as depicted in the movie Her, but Conru predicts virtual reality to be a normal part of our lives within five years. During my visit to AFF, Conru and Buckheit bring up a web cam page, showing a real woman, in real time, on the other end. With long dark hair and a tight black and white dress, she sits on a towel in a small room, typing on a computer and waiting for my command. When I click a button on the keyboard, she twitches and grabs for her crotch. I click again, and she grabs a second time. “We’re deploying teledildonics,” Conru explains, sex machines that enhance the online experience.

In this case, the woman is wearing vibrating panties, which engage when our keyboard is clicked. There’s a male attachment too: a white tube with a peach-colored vibrating interior. It reacts as the person on the other end of the line controls it. “Go ahead and stick your finger in there,” Buckheit invites me, as the anatomical jelly mold buzzes. “There are going to be pros and cons about it,” he says, “but I think there is a world where people will want to play out sexual fantasies with as much realism as possible.” Even if the people screwing you are fake.