The images couldn’t have been more different. The cover of the September 20th, 1969, issue of Rolling Stone showed a man and a child bathing in the nude in a lake, the essence of hippie gentility. A few months later, the photo on the cover of RS 50 [January 21st, 1970] was a grim antithesis: a huddled, anxious-looking crowd, shards of sunlight trying to poke through the mist. The cover line for the earlier issue – WOODSTOCK: 450,000 – was celebratory. For the latter, it was far more ominous: LET IT BLEED.

By early 1969, multi-day festivals had become part of the rock & roll landscape. But as the magazine’s staff would learn, preconceptions about what a festival could be – or how wrong things could go – were about to go out the window. The publication’s coverage of Woodstock and Altamont tested the staff like never before – and proved definitively that Rolling Stone was a home for serious journalism, no matter the topic and no matter how close to home it hit.

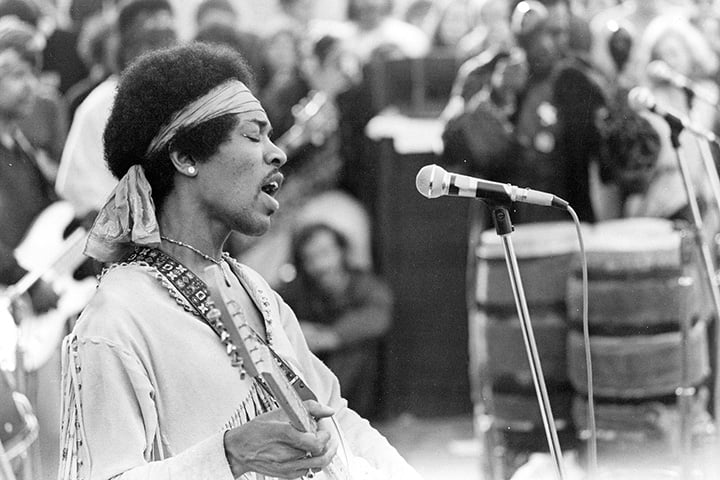

Rolling Stone, then based in San Francisco, dispatched a small team to Bethel, New York, to cover Woodstock in August 1969: New York bureau chief Jan Hodenfield, reviews editor Greil Marcus and photographer Baron Wolman. On the first day, which featured artists including Richie Havens and Melanie, Marcus wasn’t impressed with the music or the steamy, overcrowded environment, which he recalls as “unpleasant and uncomfortable.” But returning the second day, after the grounds had been battered by heavy rain and lightning, he sensed a major shift. “There was this sense of ‘we’re all trapped in this mud pile and we’re going to have a good time no matter what,'” he says. “It was impossible not to be swept up in it.”

Few, if anyone, realised how momentous Woodstock would become. “It was going to be a big event, but nobody knew how overwhelming it was going to get,” says Rolling Stone editor and publisher Jann S. Wenner. “So we crashed that cover.” Working on a tight deadline, Hodenfield filed a deeply reported story that chronicled the weekend in detail, from the crashed gates and additional security that didn’t show up through the festival’s money troubles and the mud and rain that made the crowd look like a “ravaged refugee camp.” Marcus, who had alternated between standing in the crowd and a perch by the side of the stage near musicians including Neil Young, wrote a piece that offered day-by-day commentary on the music and performances. “My piece has a lot of naiveté in it, but I felt the crowd was bringing out things in the musicians that no other circumstance would,” he says. “It was a sense of making history and living in another country, if only for a weekend.” Especially in light of the confused and often confusing coverage by the mainstream media, which didn’t know what to make of Woodstock, Rolling Stone‘s reporting became the go-to source for the glories and difficulties of that weekend.

With a lineup scheduled to include the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead, Santana, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and Jefferson Airplane, the Altamont Speedway Free Festival, in December 1969, was set to make its own kind of history. Since the show was just east of San Francisco, many from the magazine’s staff – including Marcus, managing editor John Burks, film critic Michael Goodwin, and writers Lester Bangs, Langdon Winner and John Morthland – made their way to the Altamont Speedway either to report or simply take in the music. “There was an intense desire on the West Coast to do a Woodstock even better than back East,” recalls Winner.

With a lineup scheduled to include the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead, Santana, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and Jefferson Airplane, the Altamont Speedway Free Festival, in December 1969, was set to make its own kind of history. Since the show was just east of San Francisco, many from the magazine’s staff – including Marcus, managing editor John Burks, film critic Michael Goodwin, and writers Lester Bangs, Langdon Winner and John Morthland – made their way to the Altamont Speedway either to report or simply take in the music. “There was an intense desire on the West Coast to do a Woodstock even better than back East,” recalls Winner.

Yet there was a feeling of foreboding from the start. “You got the sense as soon as you arrived that something bad was going to happen,” says Goodwin. “People seemed uptight and frightened.” Winner watched as attendees tore down wooden fence posts and set them on fire. Situated at first near the front of the stage, Marcus watched as Hells Angels, hired as security, beat a naked man with pool cues. Marcus, who would later call it “the worst day of my life,” wound up being pushed onto, and then off, the stage. He settled atop a VW bus, whose roof would eventually collapse from the weight of too many others on it. Marcus soon spotted a naked woman who had also suffered the wrath of the Angels. “She was walking toward me in a daze, and someone had given her a blanket that she was dragging behind her,” Marcus says. “She was covered in bruises and blood. It was a vision of horror unlike anything I’d seen.”

Initial reports from local newspapers, many filed before the day’s end, painted an upbeat portrait of Altamont. But by the next morning, the Rolling Stone staff learned about a series of horrors: A young African-American, Meredith Hunter, had been stabbed to death by an Angel as Hunter pulled a gun in the crowd, and three others had died, two in a hit-and-run incident and one who drowned in a ditch. At a staff meeting soon after, Burks and Marcus, shellshocked, tried to articulate the ugliness they’d seen, until Wenner helped them focus. Recalls Marcus, “I’ll never forget Jann looking across the table and saying, ‘We’re going to cover this thing from top to bottom, and we’re going to lay the blame. Get going.'” As Wenner says, “Our mission was what Rolling Stone stood for. We weren’t going to pull our punches.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

With Burks at the helm, the staff fanned out, interviewing witnesses, police, and musicians such as David Crosby and Mick Taylor. Marcus tracked down Hunter’s sister, who told him no one in the family had yet heard from anyone in the Stones’ camp. Goodwin, who had brought a tape recorder to the show, made a small but valuable contribution. When he began hearing a clearly shaken Mick Jagger address the crowd, Goodwin turned on his recorder and repeated into the machine everything Jagger was saying, giving the magazine an accidental exclusive. “We felt a responsibility,” says Marcus. “If we didn’t cover this and get out what had really happened, and what that whole day meant for the culture we’d all been a part of, this event was either going to disappear from history or go down as ‘Woodstock West,’ which is what you were hearing or reading everywhere. We had to put this into history for what it was.”

The resulting 24,000-word story, assembled by Burks and spread over 14 pages, was a terrifying panoramic that didn’t flinch from implicating the Stones, their team or the promoters involved in the show. Many factors – the last-minute change of venue to the barren raceway, the Stones’ hiring of the Angels – had come together in the worst way. “Altamont was the product of diabolical egotism, hype, ineptitude, money manipulation, and, at base, a fundamental lack of concern for humanity,” read the story. “Rolling Stone‘s coverage lifted the magazine out of the underground and established Stone as the journalistic voice of its generation,” says veteran journalist Joel Selvin, author of Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock’s Darkest Day. “Only Rolling Stone caught the real story, and the reporting they did was brilliant. Police investigating the murder had to read the issue to learn about their case. The Stone reporters knew the scene. The cops were lost.”

The resulting 24,000-word story, assembled by Burks and spread over 14 pages, was a terrifying panoramic that didn’t flinch from implicating the Stones, their team or the promoters involved in the show. Many factors – the last-minute change of venue to the barren raceway, the Stones’ hiring of the Angels – had come together in the worst way. “Altamont was the product of diabolical egotism, hype, ineptitude, money manipulation, and, at base, a fundamental lack of concern for humanity,” read the story. “Rolling Stone‘s coverage lifted the magazine out of the underground and established Stone as the journalistic voice of its generation,” says veteran journalist Joel Selvin, author of Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock’s Darkest Day. “Only Rolling Stone caught the real story, and the reporting they did was brilliant. Police investigating the murder had to read the issue to learn about their case. The Stone reporters knew the scene. The cops were lost.”

The world took notice. “Let It Bleed” contributed to Rolling Stone winning one of its first two National Magazine Awards, in the category of Specialized Journalism. (That same year, David Dalton’s prison interview with Charles Manson also won a National Magazine Award.) Coming on the heels of its coverage of the comparatively upbeat Woodstock, “Let It Bleed” detailed the way that Altamont, held in the last month of the Sixties, took on a large cultural meaning: If Woodstock was a hippie utopian dream, Altamont was the nightmare flip side. “It was the first time we’d ever had that challenge of dealing with a big news story, something very controversial, something way different than a celebration of rock and all the wonderful things going on there,” says Wenner. “It was the dark side of the hippie culture and rock & roll culture, and it challenged the assumptions and conventions of our readership and our generation. It was hard to integrate the idea of people being beaten with pool cues at a free concert.” As Marcus notes, proudly, “No one’s ever talked about ‘Woodstock West’ again.”