Besides being the two most notorious criminals in America in the early 1970s, Charles Manson and Patty Hearst had nothing in common. One was a cult leader hoping to start a race war; the other was a teenage heiress who was kidnapped by a group of inept revolutionaries. (Ironically, the demure Hearst was the only one of the two to actually participate directly in a crime.) The pair were media sensations who generated endless hours of news coverage, but it was two teams of Rolling Stone reporters that ran circles around the mainstream media, scoring exclusive, groundbreaking stories on both. In the process, the journalists elevated Rolling Stone from a small, youthful journal to a publication that could influence the national conversation.

It began in August 1969, when actress Sharon Tate was murdered along with her unborn baby and four other people in her Los Angeles mansion; the next day, a couple, the LaBiancas, were killed in their L.A. home. Manson, a songwriter and associate of Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson, was soon identified as the mastermind of the massacres, but many in the underground press thought he was innocent – including, at first, Rolling Stone. “He was a fellow hippie,” says writer David Dalton. “I thought he’d been railroaded. I was spouting this stupid hippie bullshit, like, ‘Which side are you on, man? The fucking government is corrupt!’ ”

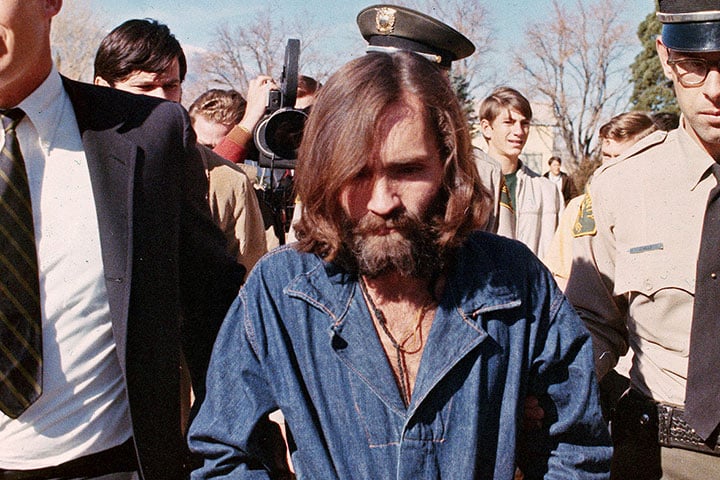

Dalton was a rock expert with personal ties to Wilson. To investigate the Manson story, Rolling Stone paired him with veteran investigative reporter David Felton. The magazine hoped to land a jailhouse interview, which was planned to run with a provocative cover line: MANSON IS INNOCENT. The cult leader was locked away in the L.A. County jail awaiting trial and had declined most interviews, but his new album, Lie: The Love and Terror Cult, was coming out and he wanted to promote it in Rolling Stone. “We had to pose as attorneys to get in,” says Felton.

Felton and Dalton faced Manson, who sported a freshly shaved beard and a freshly carved “X” in his forehead, across a table in the prison. “He kept clicking his nails on the table,” says Felton. “I could see how he’d have command over people.” Dalton felt he was connecting with a fellow hippie. At one point, he meant to say, “You’re a Scorpio, aren’t you?” but it came out as “You’re a scorpion.” “Ten different emotions flashed across Manson’s face – anger, shock, confusion,” says Dalton. “He could swing from pure, vicious racism to environmentalism to statements like, ‘I am God.’ ”

It was enough to convince Felton that this was no wide-eyed hippie being framed by police. But Dalton still believed Manson was innocent; in fact, Dalton and his wife had spent the previous week living with members of the Manson Family (including future Gerald Ford would-be assassin Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme) on Spahn Ranch, on the outskirts of L.A. “It was like any other hippie commune,” says Dalton. “We’d raid dumpsters and make a kind of stew. We’d ride horses at night. It was totally pleasant.”

Shortly after the Manson interview, Felton and Dalton talked to L.A. prosecutor Aaron Stovitz, who broke down details of the murders. “He took out this tray of photographs of the LaBianca murders,” says Dalton. “I see ‘Piggies’ and ‘Helter Skelter’ [written in blood] on the walls and refrigerator. At that instant, I knew they did it. The L.A. Police Department would have had to be geniuses to plant that.”

Dalton immediately thought of his wife, who was still living at Spahn Ranch. He raced over, persuaded her to ride a horse into the middle of the desert, and then explained that they were in danger. “We felt perfectly safe when we believed he was innocent,” Dalton says. “Now [the Family members] looked like children of the damned. Their eyes were dilated, and they all seemed to be tuned into the same harmonic vibe.” The couple went back to the ranch and staged a fight in which she accused him of infidelity, then stormed off and hitchhiked back into town. “It was a living horror movie,” Dalton says. “The paranoia in L.A. was like a loose power line writhing on the Pacific Coast Highway. It was palpable.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in Australian/New Zealand music and globally.

The couple moved into Felton’s house in Pasadena, where the two writers spent six weeks threading their notes and transcripts into a 30,000-word feature, roughly the size of a short book. Felton handled the journalistic parts, and Dalton sprinkled it with wild, experimental prose. “I have a piece at the end that’s sort of a philosophical, metaphysical reflection on the whole thing,” says Dalton. “I still don’t know if it makes any sense.”

The finished product ran across 21 pages, helping Rolling Stone win a prestigious National Magazine Award, the first for the publication. “I have a deep feeling about it even today,” says Felton. “And I’m glad Manson is still in jail.”

Four years later, Patty Hearst was ripped out of her apartment in Berkeley and thrown into the trunk of a car by a radical group calling itself the Symbionese Liberation Army. In a series of bizarre missives, the SLA said it would release Hearst if her family – heirs to the Hearst newspaper dynasty – gave $70 worth of food to every needy family in the state, which would cost $400 million. The saga riveted the nation like no story since the Lindbergh kidnapping. Many assumed Hearst had been coerced, but “Tania,” which the SLA renamed her, was soon caught on film robbing a series of banks, and chose to stay with the SLA when she could have escaped.

Rolling Stone had just landed a huge scoop with former Detroit Free Press writer Howard Kohn’s exposé about Karen Silkwood, a labor activist who died under mysterious circumstances after blowing a whistle on her chemical company. Kohn and his friend David Weir, who had ties to the Bay Area radical underground, contacted lawyer Michael Kennedy (whose client Jack Scott transported Hearst across the country in the summer of 1974). In May that year, authorities had burned down a house containing most of the SLA, a shocking event broadcast live on TV; Hearst had escaped, but her whereabouts were a mystery. Scott was ready to talk as an unnamed source, setting up Rolling Stone for the scoop of the decade. “Kohn was a classic, hard-nosed investigative reporter,” says Paul Scanlon, the magazine’s managing editor at the time. “I’ve never seen anyone that gets in and burrows like Howard.”

While the mainstream media were content to simply attend press briefings, Rolling Stone‘s reporters went on a cross-country odyssey retracing Hearst’s steps to verify the tales told to them by Scott and others. In turn, Rolling Stone editor and publisher Jann Wenner planned two Hearst cover stories. “Jann knew we were going to rely on a lot of anonymous sources,” says Kohn.

“That’s OK if you’re The New York Times and you’ve got a stack of lawyers and a history of journalistic traditions. If you’re Rolling Stone, you don’t have deep pockets or legal advice.”

The first cover story was written in secret, with only a handful of staffers even knowing about it. It was about a month away from publication when, on September 18th, 1975, Hearst was apprehended in San Francisco. “We had a couple of hours thinking the story was over, since the penultimate act was over,” says Kohn. “But Jann was clear we needed to keep going.”

A cover of Rod Stewart with girlfriend Britt Ekland was pushed back so the Hearst article could run. Guards were posted at the printing press in St. Louis so stray copies didn’t leak out early. Once the news hit that Rolling Stone had the exclusive story of Hearst’s two years on the run, the magazine was inundated with media requests. The story led every news broadcast on the networks that night, and Weir and Kohn appeared on the Today show. “I remember having a screaming match with [famed Hearst family attorney] William Kunstler, one of my heroes, on the phone,” says Scanlon. “He was trying to enjoin us from printing it.

Kunstler wasn’t the only one outraged by the story. The FBI had been outmanoeuvred by two twenty-something reporters and demanded they name their sources or face imprisonment (at the last minute, a judge allowed the reporters to skirt prison). The second Hearst cover, a month later, focused more on her family’s side of the saga, but it was also full of information from SLA members who came forward. One told Weir he would leave a packet of info at a phone booth under a freeway overpass. “I thought, ‘If they’re gonna shoot me, this is where they’re gonna get me,'” Weir remembers. “It was one of the scariest walks of my life, but I somehow got in, got out, and we had our material.”

More than four decades later, those involved in the story vividly recall the rush of events. “The memory of Rolling Stone leading off the three network news broadcasts that evening just kills me,” says Scanlon. “Patty Hearst was a leap forward in terms of credibility, in terms of convincing people yet again that it wasn’t just a rock & roll magazine from San Francisco. I can feel my adrenaline pumping just thinking about it all.”